One of history’s little mysteries is why some people become famous and others of similar, or even greater, accomplishment do not. Among those overlooked is the Cruger family of New York, which gave us two Mayors of New York City (one of whom was the host for the Stamp Act Congress), early New York’s most successful merchant trader (who built the largest wharf there), a man who gave Alexander Hamilton his first job, a brave Loyalist who fought in South Carolina, and a man who was actually an elected member of the House of Commons when war broke out and later returned to the newly created United States to serve as a New York Senator.

John and Henry Cruger were brothers living in the city of New York during the years that rebellion was fomenting in the American colonies. Their father, who died in 1744, was a merchant who had been active in politics including five years as mayor of the city.[1] It was only natural that John and Henry would also have influential roles in the events of the era.

John Cruger, Jr., Merchant of New York

It was the third son of John, Sr. who made the greatest name for himself in this generation of Crugers. Like his father, John Cruger also had political aspirations. His earliest recorded appointment was in 1746, when the Governor named him to a special commission “to meet those of the other Colonies, to concert measures for the prosecution of the War, and encouragement of the Indians.”[2] After two years’ service as alderman, and thirteen years after his father death, John Cruger, Jr., was appointed the forty-first mayor of New York City in 1756 and held that office until the close of 1765.[3] He also served in the provincial Assembly from 1759 to 1775, with an interruption in 1768, during which time he took a prominent part in resisting the attempts of the British administration to control the colonies.[4]

As part of an early attempt at looking toward a union of the Colonies against the “aggressions” of the Crown, John Cruger was appointed to the Committee of Correspondence at the first session of the 29th Assembly until it was dissolved in 1768.[5] He later played an important part in calming the situation that arose in New York City after the attempts of the English Crown to enforce the Stamp Act in the fall of 1765. The mob threatened the life of Lieutenant-Governor Cadwallader Colden and the safety of his house if the stamps were used. As a compromise, the stamps were surrendered to the mayor and corporation of the city.[6] One source reports: “A prodigious concourse of people of all ranks attended the ceremony of the transfer, Mayor John Cruger, in whom the citizens had the utmost confidence, giving Colden a certificate of receipt. The packages were then conveyed to the city hall, in Wall Street, the crowd cheering at every step vociferously. Tranquility was thereby restored to New York.”[7]

John Cruger, Jr. was also one of the New York delegates to the Stamp Act Congress of 1765.[8] As the meeting was held in New York City he was essentially the host; the meeting itself being held in City Hall.

John Cruger, Jr. was also one of the organizers of the New York Chamber of Commerce in 1768,[9] and on the occasion of his reelection as its president, May 2, 1769, he conveyed, as speaker of the Assembly, the thanks of that body to the merchants of New York for their proceedings relative to the nonimportation of British goods.

John, Jr. never married and he died in New York on December 27, 1791.[10]

Henry Cruger, Senior

The second son, Henry (who we will refer to as Henry Sr.) lived both in Jamaica and in New York, where he was a member of the Assembly from 1745 to 1759[11] and in 1767 he was appointed to the Council of New York.[12]

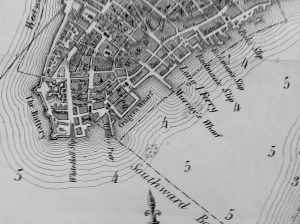

Henry Cruger Sr. and his sons engaged in an active and lucrative business among the ports of Bristol, Jamaica, Curacao, and the African Coast. In 1739 he and his partners built New York’s largest wharf. Built of 30-foot timbers along the waterfront, the wharf extended 170 feet from Clock’s corner at Old Slip and went parallel to Water Street. Cruger’s Wharf was finished in 1740, and it enclosed an area that was subsequently filled between it and the shore at Water Street.[13]

Eventually, in 1772, Henry, Sr. came to the point that he wished to relinquish his post in the Council of New York, possibly because of failing health. He attempted to ensure that the post be passed on to his son, John Harris. He made application along these lines to the Board of Trade and Plantations but the idea was not well received.[14] His brother John Jr. then attempted to lobby on his behalf by using the parliamentary agent for New York, Edmund Burke, as an intermediary. Burke was able to get a more positive response and in April of 1773 the Board approved the plan.[15]

Around May of 1775 Henry Cruger, Sr. left New York to go to Bristol, England to live with his son Henry, Jr.[16] We do not know for certain why, most sources stating that this was because of “his health being very bad,” but the true reason almost certainly is found elsewhere. One theory is that by 1776, the climate in New York had very distinctly turned against those loyal to the King. His brother, John, and colleagues of Henry Cruger on the pre-revolutionary council and General assembly, such as John Watts, and James De Lancey, were later named specifically as “adherers” under the New York Act of Attainder or Confiscation Act /[17] It seems very likely, therefore, that he simply saw “the writing on the wall” and left for more congenial climes. He died in Bristol some time in early 1780, and he was buried in Bristol Cathedral February 8, 1780,[18] but it is not at all clear exactly where his remains are located.

John Harris Cruger

Henry’s first son, John Harris Cruger, was a merchant and real-estate owner. He was well known in official society and, as we saw, in 1773 had succeeded his father as a member of the Royal Council. He and his father were both very interested in all aspects of trade and they are both cited specifically by King George III in his charter creating The Marine Society of the City of New York.[19] (Both brothers ,Henry Cruger, Jr. and Nicholas Cruger, also became members of the Society in 1774 and 1788, respectively.)

At the outbreak of the Revolution, John Harris Cruger was Chamberlain of New York[20] and very interested in trade with London. But during the period of the American Revolution, his sympathies were with the Crown, and he actually became an officer in the British army. When a Provincial Brigade was raised in 1776, under Oliver de Lancey as Brigadier General, “for the defence of Long Island, and other exigencies,” he was commissioned Lieutenant-Colonel of the 1st battalion or regiment (General de Lancey himself being the Colonel).[21] He served at Savannah, Charleston, and Camden, and was largely responsible for the defense of Fort Ninety-six in South Carolina in 1781.[22]

After the war he went to England, and resided at Beverley, in Yorkshire, where he died.[23] After the war the property of loyalists were formally confiscated by the Commission of Forfeitures for the State of New York. John Harris Cruger’s name appears in the list of estates forfeited, so it seems he was left with few resources.[24]

Nicholas Cruger

The youngest son, Nicholas Cruger (1743-1800) was reportedly one of the largest merchants in New York City by 1770. Later (some time between 1766 and 1768) he moved to Christiansted, St. Croix where he dealt primarily in West Indian trade at the Counting House of Nicholas Cruger and David Beekman.[25] This arrangement was apparently dissolved by around 1769, for subsequent ventures were undertaken under the name of Kortright and Cruger. There he came to know the young Alexander Hamilton, who was born on the Caribbean island of Nevis. Hamilton was involved in business from early age and at age twelve he served as an apprentice at the Cruger Counting House. He evidently showed such talent in finance that, at age fifteen, he was put in charge of the business when Nicholas Cruger went to New York for five months in 1771.[26] There are many letters between Hamilton and Nicholas Cruger extant in Hamilton’s papers.[27]

In the revolutionary war Nicholas Cruger contributed generously to the colonial cause. It is reported that he also had an exciting time during the hostilities, being twice arrested and imprisoned for being a rebel.[28] At the close of the war, Nicholas was the chief man on the committee that met Washington in New Jersey and accompanied the general on his triumphal entry into New York.[29] Nicholas died March 11, 1800 in Santa Cruz, West Indies.

Henry Cruger, Jr.

Henry, Jr., as the second son, was allowed to start out by getting an education. He was enrolled in Kings College (now Columbia University) in the very first class of eight students, but he did not graduate, attending only from 1754 to 1757.[30] Instead, according to the family histories, his father sent him to Bristol in England.

When Henry Cruger arrived in Bristol in 1757, he found a provincial city that was second only to London as a port and one with long trading ties to the Americas. Although not comparable to London, Bristol was nevertheless a large city. In 1750, its population was around 45,000.[31] By comparison, New York’s population had not yet reached 18,000.[32]

Bristol’s Atlantic import trade was predominantly in tobacco and sugar rather than other types of commerce; these used more shipping tonnage and had higher value than any other colonial imports arriving there in the eighteenth century. Nearly seventy-five percent of the tonnage coming to Bristol from the Americas was from the Caribbean and the Chesapeake. There was little overlap between them and the prominent Bristol slave traders.

Henry Cruger’s Early Years In Bristol

On arrival in Bristol in 1757 Henry Cruger, Jr., soon took several steps to get himself involved in and accepted by the local merchant community. He soon joined the Society of Merchant Venturers. This organization, founded in 1552 and which still exists today, was an elite body of Bristol merchants involved in overseas trade.[33] It is reported that that he also accepted the Anglican faith (the Cruger family were Dutch Reformed Church members) and became an active member and a churchwarden of St. Augustine-the-Less. He gave them a new organ in 1770.[34]

On November 14, 1765, he had taken the further step of marrying into society, taking as his bride Ellen Peach, daughter of Samuel Peach.[35] Samuel Peach was at that time one of Bristol’s wealthiest and most prominent merchants and this marriage allowed him to become a freeman (or burgher) of the city,[36] which was necessary at that time in order for him to purchase property and to become a merchant. Although Ellen died rather soon after (perhaps in 1767),[37] they had a son whom they named Samuel Peach Cruger. Samuel later took the Peach name (becoming Samuel Peach Peach) and inherited his grandfather’s estates.

A John Mallard also became a burgess on June 2, 1770, and by 1775 Henry Cruger formed a partnership with him to create the company of Cruger & Mallard.[38]

While he became more and more entrenched in Bristol society, Henry never forgot his links to New York. He involved himself in the problems of the relationship between the colonies and the English administration and carried on detailed discussions with correspondents in America on strategies to deal with these difficulties.[39] He supported and even co-authored “memorials” (i.e. petitions) to the administration in London decrying the impact of the government’s tariff, duties, and other trade policies with respect to the colonies and the West Indies.[40] When the government fell in 1774, the local Whigs in Bristol decided to abandon the previous strategy of agreeing to split the two House of Commons seats between them and the Tories in favor of offering two candidates on their “platform.”[41] Edmund Burke was looking for a seat, so the Bristol Whigs invited him to head the ticket and provide a national stage and drafted Henry Cruger to represent the merchant class. Henry Cruger turned out to be the more popular of the two and in the polls received 3,565 votes and Burke 2,707. The other two candidates received 2,456 and 283 votes, respectively. In his maiden speech in the House on December 16, 1774 Cruger, quite naturally, chose to rise in a debate on the subject of Government policy towards the colonies. He took a measured tone, starting by admitting that the colonists had not helped their cause by turning to civil unrest:[42] “I am far from approving all the proceedings in America. Many of their measures have been a dishonour to their cause. Their rights might have been asserted without violence, and their claims stated with temper as well as firmness. But permit me to say, sir, that if they have erred, it may be considered as a failing of human nature. A people animated with a love of liberty, and alarmed with apprehensions of its being in danger, will unavoidably run into excesses…”

But he made it clear that he decried the Government’s policies of coercion: “Why, then, strain this authority so much, as to render a submission to it impossible, without a surrender of those liberties which are most valuable in civil society, and were ever acknowledged the birthright of Englishmen? When Great Britain derives from her Colonies the most ample supplies of wealth by her commerce, is it not absurd to close up those channels, for the sake of a claim of imposing taxes, which (though a young Member) I will dare to say, never have, and probably never will, defray the expense of collecting them?”

And he expressed a wish that a reasonable compromise could be created: “… it may be hoped, that a different plan of conduct maybe pursued, and some firm and liberal constitution adopted by the wisdom of this House, which may secure the Colonists in their liberties, while it maintains the just supremacy of Parliament.”

Despite the fact that Henry was an elected Member of Parliament, Lord Dartmouth ordered the Post Office to secretly intercept letters from several American colonists, including him, starting in 1775.[43] The letters included correspondence with his father, his brother John Harris, and his brother-in-law Peter Van Schaack. Correspondence between Henry Sr. and Edmund Burke was also intercepted.

Henry Jr. made other speeches in Parliament regarding American issues, all the time warning of disaster if common ground could not be found: “…we were now like men walking on the brink of a precipice; that there was danger in every step, and that in his opinion the salvation of this country depended on the measures that were adopted by the House …”[44]

When a new election was called in the fall of 1780, the Revolutionary War was still raging (the surrender of Yorktown not occurring until October 1781). Voters were clearly uncomfortable with having members of parliament so closely aligned with American interests and neither Henry Cruger nor Edmund Burke were returned to office.[45] Henry returned to Bristol and was elected Lord Mayor of Bristol in 1781.[46]

After the Revolutionary War was over, he was re-elected to Parliament in 1784.[47] In this session, the issue of slavery started to be raised and William Wilberforce moved resolutions leading to abolition. Petitions against the proposals were presented by Henry Cruger on behalf of the Bristol Corporation and of the principal merchants and traders of Bristol. In these they urged that the trade should be regulated and gradually abolished; but insisted that if abolition was the chosen path, the “injured interests” should receive compensation, estimated at from sixty to seventy millions sterling.[48] We know little more about Henry Cruger’s personal attitude towards this issue, although the census records from his later residence in New York lists slaves in his household, many of whom he later manumitted.[49]

In 1790, while still an MP, he announced his intention not to run in the anticipated upcoming election and he departed for New York with his family on April 8 and arrived in New York on June 4.[50] The previous election had been ruinously expensive and there is evidence that he was not in a firm financial position at that time.[51]

Henry Cruger’s Years in New York

Henry Cruger apparently had contacts with John Jay as well as Alexander Hamilton, so it was natural that when he returned to his new country he became interested in New York politics. He ran as a Federalist candidate for one of the three State Senate seats being contested in the Southern District in the election of April 1792.[52] He was elected, together with fellow-Federalist Selah Strong and Democratic-Republican John Schenck.

On leaving the New York Senate in 1796, after only one four-year term, Henry Cruger retired to his house in New York City. He was only fifty-seven and would live for more than thirty additional years. Little is known, however, about what he did during those years, other than sire four children between 1798 and 1810. In 1799, a notice appeared in the Albany Centinel that he was admitted to the State Bar,[53] but no records have been found that he subsequently practiced law. Advertisements in New York newspapers suggest that the Cruger firm was still somewhat active in trading; several notices appeared in the New York Daily Gazette in 1817 offering imports from Bristol and Jamaica and referencing a trading address at 1 Smith Street. But the Cruger operation in London, which first appears in the London Directory in 1784,[54] disappeared after 1797.[55] The censuses of 1790, 1800, and 1820 show him as residing in New York City. According to his obituary in The Watch-Tower of Cooperstown, New York, he lived for some years on Long Island before returning to the city; this is consistent with a record of a Henry Cruger living in Flatbush (which was considered part of Long Island at the time) in the 1810 census. We do not know much about his financial position over these years, although there is a notice in the March 17,1885 edition of the New-York Packet about the sale for back-taxes of a house assessed to him in Hanover Square.

Henry Cruger, Jr. died April 24, 1827 at his house at 382 Greenwich Street, New York City and was buried in the Cruger vault under Trinity Church[56]. The Bishop, John Henry Hobart, officiated.[57]

[1] Various biographers differ, but it is a reasonable consensus position that the first John Cruger was born around 1678, came from Holland to New York City shortly before the turn of the century, and established himself there as a merchant and factor. By 1712 John Cruger had become sufficiently well connected to be elected Alderman of New York City. In 1739 he was appointed the thirty-eighth mayor of New York City by the colonial governor of the province, George Clarke, a post he held until his death in New York on August 13, 1744. Sources include Edward F. De Lancey, “Original Family Records, Cruger,” The New York Genealogical and Biographical Record Volume VI (1875), 74-80 (corrected 180-182), which provides no information regarding his sources beyond the privately held family bible that documents the births and deaths of the first generation; and Douglas Wright Cruger, A genealogical and biographical history of the Cruger familes [sic] in America (Portland, ME: D.W. Cruger, privately published, 1989) which, as he was a member of the family, one assumes that he also had access to privately held material. Also, see “John Cruger“, Dictionary of American Biography, 2:581- 582.

[2] John Romeyn Broadhead, Documents relative to the colonial history of the State of New York Vol. VI London documents : XXV – XXXII, 1734-1755 (Albany NY: Weed, Parsons, 1855).

[3] Edward F. De Lancey, The burghers of New Amsterdam and the freemen of New York. 1675-1866 (New York: Printed for the Society, 1886).

[4] John Romeyn Broadhead, Documents relative to the colonial history of the State of New York Vol. VII London documents : XLI – XLVII, 1768-1782 (Albany, NY: Weed, Parsons, 1857).

[5] Edgar Albert Werner, Civil list and constitutional history of the Colony and State of New York (Albany, NY: Weed 1888).

[6] James Grant Wilson, “The memorial history of the City of New-York, from its first settlement to the year 1892 Vol. II (New York: New York History Co., 1892).

[7] Martha J. Lamb, “Wall Street in History. I-II,” The Magazine of American History with notes and quotes Vol. IX, January to July, 1883, Historical Publication Co., New York.

[8] James Grant Wilson, The Memorial History of the City of New-York: From Its First Settlement to the Year 1892 (New York: New York History Co, 1893).

[9] New York Chamber of Commerce, and John Austin Stevens, Colonial records of the New York Chamber of Commerce, 1768-1784. With historical and biographical sketches (New York: John F. Trow & Co. 1867).

[10] Holland Society of New York (New York City), Record of burials in the Dutch Church, New York City, Holland Society of New York, 1899 (Salt Lake City, Utah: Filmed by the Genealogical Society of Utah, 1980), 139-211.

[11] In 1747 he was one of four assemblymen appointed to a commission to meet with the other colonies regarding “the prosecution of the war, and the encouragement of the Indians.” See Broadhead, Documents.

[12] See also: Benson John Lossing and H. Rosa, The Empire State: a compendious history of the Commonwealth of New York (Spartansburg, S.C.: Reprint Co., 1968).

[13] Paul R. Huey, “Old Slip and Cruger’s Wharf at New York: An Archaeological Perspective of the Colonial American,” Historical Archaeology, Vol. 18, No. 1 (1984), 15-37.

[14] K. H. Ledward, ed., Journals of the Board of Trade and Plantations, Volume 13: January 1768 – December 1775, 1937.

[15] Ibid.

[16] Henry Cruger Van Schaack, The life of Peter Van Schaack, LL. D. embracing selections from his correspondence and other writings during the American Revolution, and his exile in England (New York: D. Appleton, 1842).

[17] Thomas Jones and Edward F. De Lancey, History of New York During the Revolutionary War, and of the Leading Events in the Other Colonies at That Period. Vol. 1 (New York: New York Historical Society, 1879).

[18] Bristol Diocese burial registers, volume 3, index and transcripts 1754-1812 (Bristol Records Office, Bristol, UK).

[19] Marine Society of the City of New York, in the State of New York, The Marine society of the City of New York, in the State of New York (New York: H. Bessey, printer, 1913).

[20] Herbert L. Osgood, Austin Baxter Keep, and Charles Alexander Nelson, Minutes of the Common Council of the city of New York, 1675-1776 (New York: Dodd, Mead, 1905).

[21] Great Britain, Orderly book of the three battalions of loyalists, commanded by Brigadier-General Oliver De Lancey 1776-1778 to which is appended a list of New York loyalists in the city of New York during the war of the revolution (New York: New York Historical Society, 1917).

[22] Cruger, Memorial; Alexander Stewart to Cornwallis, September 9, 1781, Cornwallis Papers; Royal South Carolina Gazette.

[23] Jones and De Lancey, History of New York.

[24] Erastus C. Knight and Frederic Gregory Mather, New York in the Revolution as colony and state, supplement (Albany, N.Y.: O.A. Quayle, 1901).

[25] Robert A. Hendrickson, Hamilton I (1757-1789) (New York: Mason Charter, 1976).

[26] Richard Brookhiser, Alexander Hamilton, American (New York, NY: Free Press, 1999).

[27] Harold Syrett and Jacob E. Cooke. The papers of Alexander Hamilton. New York (New York: Columbia University Press, 1962).

[28] Margherita Arlina Hamm, Famous families of New York: historical and biographical sketches of families which in successive generations have been identified with the development of the nation (New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1902).

[29] Hamm, Famous families of New York.

[30] Milton Halsey Thomas, Columbia university officers and alumni, 1754-1857, compiled for the Committee on general catalogue (New York: Columbia University Press, 1936).

[31] Palgrave Macmillan (Firm), International historical statistics (Basingstoke, England: Palgrave Connect, 2010).

[32] B. R. Mitchell, International historical statistics: the Americas, 1750-1993 (London: Macmillan Reference, 1998).

[33] John Latimer, The annals of Bristol in the nineteenth century (Bristol: W. & F. Morgan, 1887).

[34] Werner Laurie, The City and County of Bristol (London: Little, Bryan, 1954).

[35] Bristol Records Office.

[36] George Edward Weare, Edmund Burke’s connection with Bristol, from 1774 till 1780 (Bristol: W.Bennett, 1894).

[37] Felix Farley’s Bristol Journal, February 7, 1767.

[38] Bristol Records Office.

[39] These “conversations” were with such people as his uncle John, his father Henry, John Hancock and others. There are too many examples to cite here. An example is found in Ralph Izard and Anne Izard Deas, Correspondence of Mr. Ralph Izard, of South Carolina from the year 1774 to 1804; with a short memoir. Vol. 1 (New York: C.S. Francis, 1844).

[40] There are many examples in the Bristol Records Office.

[41] P. T. Underdown, “Henry Cruger and Edmund Burke: Colleagues and Rivals at the Bristol Election of 1774,” The William and Mary Quarterly, 1958, 15 (1): 14-34.

[42] There is no official transcript of the speech (in fact, recording speeches in The House was technically illegal at that time). This extract is from one version: George Johnstone, The Second Parliament of George the 3d (New-York: Printed by James Rivington, 1775).

[43] Julie M. Flavell, “Government Interception of Letters from America and the Quest for Colonial Opinion in 1775,” The William and Mary Quarterly, Third Series, Vol. 58, No. 2 (Apr., 2001), 403-430.

[44] William Cobbett, J. Wright and T. C. Hansard, The parliamentary history of England, from the earliest period to the year 1803. From which last-mentioned epoch it is continued downwards in the work entitled “Hansard’s Parliamentary debates,” Vols 18,20 & 21 (London: Longman, Hurst, Rees, Orme & Brown, 1806).

[45] Lewis Namier and John Brooke, The history of Parliament: the house of Commons, 1745-1790 (London: H.M.S.O., 1964).

[46] Bristol Records Office.

[47] Namier, The history of Parliament.

[48] Cobbett, The parliamentary history of England, Vol. 28, 95-96.

[49] Harry B. Yoshpe, “Record of Slave Manumissions in New York During the Colonial and Early National Periods,” The Journal of Negro History, Vol. 26, No. 1 (January 1941), 78-107.

[50] State Gazette of South-Carolina, June 24, 1790.

[51] Joseph Leech, Brief romances from Bristol history: with a few other papers from the same pen; being cuttings from the columns of the “Bristol Times,” “Felix Farley’s Bristol Journal,” and the “Bristol Times and Mirror,” during a series of years extending from 1839 to 1883 (Bristol: William George and Son, 1884).

[52] Edgar Albert Werner, Civil list and constitutional history of the Colony and State of New York (Albany: Weed, 1888).

[53] The Albany Centinel, April 30, 1799.

[54] T. and W. Lowndes, Lowndes’s London directory for the year 1784 Containing an alphabetical list of names and places of abode of the merchants and principal traders of the cities of London and Westminster (London: Printed for T. & W. Lowndes, 1784).

[55] T. and W. Lowndes, A London directory, or alphabetical arrangement; containing the names and residences of the merchants, manufacturers, and principal traders, in the metropolis and its environs … Embellished with a plan of the Royal Exchange (London: Printed for H. Lowndes, 1797).

[56] Trinity Church Records.

[57] Henry C. Van Schaack, Henry Cruger: The Colleague of Edmund Burke in the British Parliament: A Paper Read Before the New York Historical Society, January 4th, 1859 , available through Forgotten Books, 2012.

20 Comments

Mr. Mason, Is the Selah Strong the Federalist elected with Henry Cruger in 1792 the same as Selah Strong (December 25, 1737 – July 4, 1815)?

Also, I believe the line “The packages were then conveyed to the city hall, in Wall Street, the crown cheering at every step vociferously.” was probably meant to read crowd instead of crown.

Thank you for a fascinating read about a family I was woefully ignorant of.

Dan

Thanks for the correction– several proofreaders missed that.

I’m not sure about the Strong question; I’ll have to check.

Well done, Mr. Mason.

Thr photo of the gentlemen in the red cloak is not Henry Sr. but Henry Jr. i have been intensely researching the Cruger family for about a year, i was shocked to see your article on this obscure but very important family. I have been searching for the biological father of Alexander Hamilton and Corcumstantial evidence points to a member of the Cruger family.

That is correct; it is HC, Jr. The publisher used the citation as specified by the license-holder of the photo. In fact he is wearing his Mayoral robes that he apparently took with him when he returned to NYC. The picture hangs in the Mansion House in Bristol — the official residence of the Lord Mayor of Bristol.

As for Hamilton — although Nicholas employed him I have seen no hint that there was any other connection.

I am working on a full biography of NC, Jr.

Alexander Hamilton was Nicholas Cruger’s little half-brother. What was Henry Cruger, Sr. doing on Nevis and St. Kitts at the time of Hamilton’s conception? Conducting business on his way back to New York from Jamaica. He traveled traveled back and forth on his own company ships that stopped at all the ports in the British West Indies. In Nevis, he would pick up slaves. He was able to do this since the breakup of The Royal African Company monopoly in 1752. St. Kitts was a regular stop along the way through the Leewards to New York. On March 9th of 1754, an good approximate date for Hamilton’s conception, he was on his way to take his seat at the New York Assembly on April 9th. Henry likely knew Hamilton’s mother since her birth. It was likely that Henry was recalled from Bristol by his father, in 1730, and ordered to manage the business in the West Indies after his oldest brother, Telemon died after contracting a disease on Curacao. Being suppliers of slaves to the sugar plantations of the Britsh colonies of the Carribean, Henry would have spent much time in Nevis, the entreport of slaves to the British West Indies – the headquarters of The Royal African Company. Rachel Fawcette was born circa 1730 when Telemon Cruger passed away. Henry likely employed her father, who was a doctor on Nevis who lived hear the docks of Charlestown where the slaves were unloaded. Doctors were employed by the Royal African Company agents and contractors, which Henry most likely was, to restore vitality to off-boarding slaves and prepare them for sale and sail to inter-colonial ports around the Caribbean or the mainland. The fact that Henry married Emily Harris, the daughter of a Jamaican doctor, is further proof of his association with doctors involved in the slave business. Of Alexander Hamilton was a work-a-holic, most likely his father was too and had no time to dilly-dally with dating. A doctor’s daughter was a convienient meet. After he was married to Emily he followed the disastrous love life of Rachel, likely through inquiry, rumor and meeting. He probably supplied her and James with slaves and dry goods. Being an old friend and sympathetic likely led to physical affection being so far from his wife.

This is pretty interesting, if provocative. BTW, I note your name — is it a corruption of Schaack?

Good question but no. Just a coincidence.

My mother’s family were the Crugers. My mother repeatedly told us, while we were growing up, that Hamilton was fathered by a Cruger. She was convinced. I love this article and so nice to read so much history. Thank you.

I have prepared a revised and corrected version of the marriage and issue of Henry, Jr. If you are interested, I could email it to you.

After a year of focused forensic research into the mystery of Alexander Hamilton’s paternity mystery, it became clear to me that Henry Cruger, Sr. had fathered AH. It doesn’t amaze me that no one had picked up on it. Biographers don’t have the time or inclination to commit their time and resources to the subject. I amassed a small library during my quest. The smoking gun is Hamilton’s business correspondence with Henry Sr. At first, I thought his father may have been William Walton, the son of Capt. Wm Walton. It was in his mansion that Hamilton founded the Bank of New York in 1784. Walton occasionally sailed his own ships down to the Caribbean. Henry Cruger, Sr. lived in Jamaica, in St. Andrews parish. A close study revealed that he was the prime candidate to be the father of AH. At the time of Hamilton’s conception, Henry Sr. was enroute from Jamaica to New York City to take his seat at the New York Assembly. Nevis, St. Kitts and Statia would have been regular stops along the way for his ships upon which he sailed.

Your mother was correct. Alexander Hamilton is your family’s secret legacy. The Cruger Bros. knew the Hamilton family via the linen trade. The Crugers were major suppliers of sought-after American flax seed to Europe. The Hamiltons we’re kind enough to foster Henry’s illegitimate son. The Crugers knew Thomas Stevens through the tobacco trade. He was also a member of the same church as Henry’s son, Nicholas on Santa Cruz (St. Croix). He too would help foster the young Alexander after his mother died. The yet unmarried Nicholas was not in a position to take in Alexander. It was enough that he was training Alexander. The Caribbean mercantile world was a very small world indeed.

Hey hey –

So amazing to read this – your validation from the Cruger family. May I speak or email with you?

Sincerely yours,

Michael S

Reserach Historian Second Infantry Light Dragoons

I would be very interested in receiving your revised version of the marriage and issue of Henry, Jr.

I don’t know how to get it to you

The reason for the secrecy surrounding Alexander Hamilton’s paternity is quite simple. John and Henry Cruger’s father, John Sr., married Maria Dirckse Cruger (Cuyler), and hence, into the most politically powerful family of Colonial New York. The Cuylers are direct descendants of Peter Stuyvesant. Stuyvesant was married to Judith Bayard. This may she’d some light on Alexander Hamilton’s close friendship with William Bayard, Jr.. it was in Bayard’s house on Jane Street in Greenwich Village where the mortally wounded Hamilton passed away.

Alexander Hamilton’s secret affiliation to the New York power base was imperitive for the successful federalizatiin of the thirteen independent former British American colonies.

The colonies had no idea that they had been roped and tied by the New York Old Dutch power base. This ignorance continues to this day among the fifty United States. All because no one took the time needed to identify the father of Alexander Hamilton.

The young, scrappy and hungry immigrant from Nevis continues to propagate his cover story for future generations.

The tight-lipped father of modern America certainly didn’t throw away his shot.

Isaac Roosevelt together with John Cruger, Jr. founded the New York Chamber of Commerce. Roosevelt succeeded fellow founder Alexander Hamilton as the second president of the Bank of New York. Roosevelt lived across the street (Queen Street) from William Walton in whose mansion the bank was founded. The mansion was a block away from Fraunces Tavern where George Washington frequented.

This may explain why General Washington took so quickly to the young immigrant from Nevis.

This may also explain the two Roosevelt presidencies and their connection by blood and marriage to

John Adams, John Quincy Adams, Ulysses Grant, William Henry Harrison, Benjamin Harrison, James Madison, Theodore Roosevelt, William Taft, Zachary Taylor, Martin Van Buren, and George Washington.

As for the Bush connection…

Flora Sheldon, wife of Samuel P. Bush, was a distant descendant of the Livingston, Schuyler, and Beekman families, prominent New Netherland merchant and political patrician families.

This is all incredibly interesting. My mother’s step-father was Randolph Cruger. He and his father, also named Randolph Cruger, with the nickname of “Dox”, both musicians, were the black sheep of the Cruger family. They owned a home in old Howard Beach, NY, not too far from Flatbush where one of the Crugers mentioned spent time. Anyway…my “Pappy”, as we called him, Randolph Jr., used to say, jokingly, that his family came over on the Mayflower. My family and I have been trying to connect the dots to the old Crugers. I did find some interesting info in the old train station, now a library, in Garrison, NY about some descendants. I know Randolp Jr. and Sr. had strong connections to the Hudson Valley/ Catskill region. Is anyone aware of a thorough Cruger family tree that may be available?

Hi there,

I grew up in Crugers, NY, right down the road from Oscawana where a later Nicholas Cruger built his mansion in the 1800’s.

I read that the Hamlet was named after John Peach Cruger, who was John Cruger’s great grandson. Would you happen to know anything about the later Crugers that lived in the Oscawana (Crugers) area of Westchester County, NY?

The property where Crugers Mansion stood later became known as McAndrews estate. It was abandoned and later demolished in the late 1960’s. The old Oscawana train station was less than a quarter mile from the Cruger mansion and 2 other mansions on the property. The ruins of very elaborate water pump houses, a horse racing track with judges stand, decorative fountains etc are still scattered throughout the wooded property. I’ve always been confused as to how this incredible place right on the river with a train station attached could have been neglected for so long to the point where it had to be demolished…. never made sense to me.

In reading deeper into the family history and business dealings I have a theory that the property may have been used in the mid – late 1800’s as a retreat for very wealthy/powerful NYC businessmen and politicians… possibly with strong masonic ties. The fact that the history is so cloudy makes me wonder if something bigger happened there.

https://scenesfromthetrail.com/2018/11/21/mcandrews-estate-oscawana-county-park/

The history that I have been able to dig up on this site is very choppy and seemingly incomplete. If you could offer any insight that would be greatly appreciated… If nothing else, I hope this peaked your interest.

Have a nice weekend!

-Dan Curtis

I was on a Zoom event today about the Jewish roots of Alexander Hamilton.

There was one interesting fact that the presenter did not elaborate about: We all now that Hamilton started to work at a very early age for the Dutch merchant family of Beekman & Cruger in Nevis, who were form NYC. It was also mentioned that Alexander learned to speak Dutch. It is therefor no wander in my opinion that, through George Washington, he met general Philippe Schuyler, who reported directly to GW. He was then invited by the General to come spend some time with the family in Albany, NY, where Philippe Schuyler had made a fortune. But there was an ulterior motive: the General had 3 daughters who were at the age that they needed to start their own families!

Alexander picked Elisabeth and they were married in December of 1780. Her mother was a van Rensesselaer, which was an old Dutch family from NYC. so, Elisabeth was 100% Dutch. I am sure that they conversed in Dutch.