Henry Defendorff enlisted as a sergeant in Christopher P. Yates’s Tryon County company of the 2nd New York Provincial Battalion commanded by Col. Goose Van Schaick, on July 20, 1775. The position of his name on the company muster roll indicates he was the company’s second sergeant.[1] The original company didn’t exist for long; shortly after the surrender of Fort Chambly in October 1775, it was disbanded and rebuilt under 1st Lt. Andrew Finck to finish out the year.[2] Defendorff joined the company officer corps with a promotion to 2nd lieutenant in November.[3]

In February 1776, Finck and his men were absorbed into the new unnumbered Continental battalion commanded by Col. Goose Van Schaick, as the 4th company. Finck was promoted to captain. Defendorff continued as 2nd lieutenant, but was soon promoted to 1st lieutenant in July. He was climbing the ranks quickly, though his service with the battalion in 1776 was spent mostly on furlough in Albany, New York.[4]

During this period there were two events that directly involved Defendorff as an individual. The first occurred in late May 1776, when Capt. Joseph Bloomfield of the 3rd New Jersey Regiment was traveling east on horseback from Johnstown, New York, on regimental business. He was surrounded by about twenty Loyalists some five miles outside of Albany. Bloomfield wrote in his journal that they claimed that Lt. Col. Anthony Walton White, of his regiment, had earlier confiscated the horse and that they:

…were determined to dismount me, upon which I took out my Pistols out of my Pocket & told them I would be the death of two of them at least if they did not let go of the Reins of the Bridle immediately, that I would after discharging my Pistols, make use of my sword & sell my life as dear as possible before they should have the Horse….

…By this time Mr. Defendaff a Lieut. in Col. Van Schaick’s Regt., came up drew his sword & said He wod stand by me to the last, which struck such a Terror in those Cowardly Rascals that they left me to take the Road with my Horse as I pleased….[5]

The second, less dramatic, event happened around July 24, 1776, when Defendorff carried a message to the General Hospital at Fort George informing them that “a large number of sick are coming.” The documentation does not show any written message, who sent him, or why he was selected, though the confirmation of his arrival was sent back to Maj. Gen. Horatio Gates.[6]

Both events clearly demonstrated Defendorff’s true character as a reliable and brave officer, yet somewhere along the way his superiors labeled him as “middling.”[7] So, when the powers-that-be got together in Saratoga, New York, to determine who should be recommended to the New York Provincial Congress Committee of Arrangement for officer’s commissions in 1777, he was passed over.

All was not lost, however, for on December 9, 1776, Jacob Cuyler, a leading member of the Committee of Safety, Correspondence, and Protection in Albany, NY wrote to William Duer, New York Provincial Congressman and a member of the Committee of Arrangement that:

Mr Henry Devandorph, who was given up to us as indifferent, has, since we were at Saratoga, done some very extraordinary services. This I have from Col Van Schaack; and I believe he will make a good officer. He is full of spirit and pride I know, and from what I can learn, he is sorry for the offence he has given some time ago to one of his Field Officers.[8]

The particular offense is unknown, but it appears pretty clear who the offended officer was. In view of the fact that the 2nd New York in 1775 and Van Schaick’s (unnumbered) New York battalion in 1776 had the same field officers, it had to have been Col. Goose Van Schaick, Lt. Col. Peter Yates, or Maj. Peter Gansevoort.[9] Of the three, only Colonel Yates, appears to have been the type of officer to report even a minor offense to his immediate superior. This was borne out back in 1775 when Yates had Capt. Joel Pratt of the 2nd New York arrested and court-martialed, at Fort Ticonderoga, over their exchange of words regarding Pratt’s not filling out a troop return correctly.[10]

Lucky for Defendorff, Colonel Van Schaick would go even further than he had earlier in the month and write to the Committee of Arrangement late in December. There he took “…the liberty to recommend to the notice of the Committee, in the room of those who declined for lieutenants…,” several gentlemen he felt worthy. One of them was Henry Defendorff.[11]

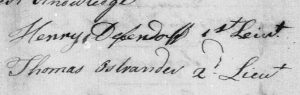

As a result, right after the third establishment of the Continental Army was formed in late 1776; Henry Defendorff was commissioned 1st lieutenant of the 1st company of Col. Goose Van Schaick’s 1st New York Regiment, but was soon inexplicably transferred to Col. Peter Gansevoort’s 3rd New York’s 1st company instead.[12]

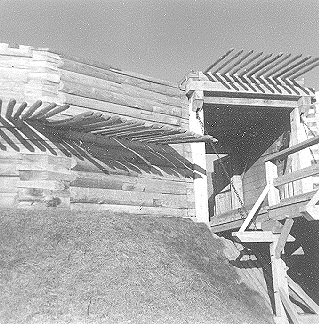

Defendorff would be with the 3rd New York regiment during the siege of Fort Schuyler in August of 1777. In fact, with the enemy closing in, he was to take a key part. According to the journal reportedly penned by Ensign William Colbreath of the 3rd New York, on August 6, 1777:

This morning the Indians were seen going off from around the garrison towards the landing; as they withdrew we had not much firing. Being uneasy lest the Tories should report that the enemy had taken the fort, Lieut. Diefendorf was ordered to get ready to set off for Albany this evening to inform General Schuyler of our situation, but between nine and ten this morning three militia men arrived here with a letter from General Harkeman [Herkimer] wherein he writes that he had arrived at Orisco [Oriskany] with 1,000 militia, in order to relieve the garrison and open communication, which was then entirely blocked up, and that if the colonel should hear a firing of small arms, desired he would send a party from the garrison to reinforce him. General Harkeman desired that the colonel would fire three cannon, if the three men got safe into the fort with his letter, which was done and followed three cheers by the whole garrison.[13]

A relief column under the command of Lt. Col. Marinus Willett, including Defendorff’s “thirty as flank guards” under the command of other officers, was quickly sent out. Covering just a half-mile, it came upon an enemy encampment which they routed and plundered. After taking a number of casualties, the column did not proceed, but returned to the fort with their booty. Herkimer’s militia column was ambushed at Oriskany that very day, where they stopped the enemy, but took very heavy losses.[14]

Defendorff presumably remained at Fort Schuyler until he signed a testimonial letter from the officers of the 3rd New York to their commander, Col. Peter Gansevoort, on October 12, 1777.[15] He was subsequently listed on the rolls as being on recruiting duties through early April 1778, despite having resigned on November 1, 1777, by leave of Colonel Gansevoort.[16] Why he remained on duty those extra months is not explained. Defendorff is known to have returned to Fort Schuyler, as he co-signed his company’s muster roll that was filled out there in April 1778.[17] He was finally omitted from the rolls in May 1778.[18]

One answer to this question might be found in the record of John Ball, former 1st lieutenant of the regiment’s 5th company, who was veteran of Willett’s sortie out of Fort Schuyler. Similar to Defendorff, he “went to resign by leave of Col. Gansevoort” on December 29, 1777. Unlike Defendorff, he filed an application for a Federal pension, which explains that “…there was an arrangement by order of Congress to reduce the number officers and it was the misfortune of Lieut Ball (he being the oldest Lieut in the Regiment) to have his further services dispense with.”[19]

As part of a sweeping resolution, dated November 24, 1778, the Continental Congress reinforced that:

Whereas from alteration of the establishment and other causes, many valuable officers have [been] and may be omitted in the new arrangement as being supernumerary, who, from their conduct and services are entitled to the honorable notice of Congress…and that all supernumerary officers be entitled to one year’s pay of their commissions respectively….[20]

Attrition was far greater among the Continental Army’s enlisted men, necessitating a way to force the excess officers to retire. (The New York regiments would go through a further downsizing in October 1780 when they reduced from five down to two Continental regiments.) They became known as “retired supernumerary officers,” even though, at least in the 3rd New York, they were listed as resigning. Such inaccuracies could lead to administrative trouble for officers like John Ball when filing for pension, even though during the war, they seemed to know the situation. Defendorff, for example, would later be described as “retired as Supernumery,” so he clearly did not voluntarily resign, but was, in fact, retired.

To this point, Henry Defendorff had spent much of his time in the Continental Army on individual service. While with Van Schaick’s Battalion in 1776, he was on furlough in Albany for as much as eleven months. During this period he had performed some unspecified “very extraordinary services,” delivered a message to the Fort George Hospital, and had come to the aide of Capt. Joseph Bloomfield. With the personal assistance of the Colonel Van Schaick, Defendorff received a high-placed 1st lieutenant’s commission in the new arrangement for 1777, but was suddenly transferred to another regiment. While with that new regiment, he was selected to carry an important message personally to Major General Schuyler. Why him? Clearly, there is more to Defendorff’s story than meets the eye.

The only portion of that story that appears customary is that when Defendorff was off recruiting, there were six other company officers in the regiment doing the same thing.[21] On the other hand, with his previous service in mind, one would question if he was really recruiting. Unfortunately, lacking any supporting documentation or a pension deposition there is not much that can be proved one way or the other.

After his retirement from the 3rd New York, Deffendorf appears as a householder in Middletown Township, New Jersey, in December 1778, March 1779, and in 1780. This township is on the New Jersey shore at Sandy Hook Bay, just below Staten Island. His wife, Hannah, and son were living with him. There appears to be no record of his son’s age. At one point in late 1780 or early January 1781, while he and the family were up in Newark, New Jersey, they were taken prisoner, for no documentable reason, by the British and transported to New York City.[22]

Given the choice of imprisonment or enlisting in a Loyalist regiment, Defendorff enlisted on January 25, 1781, as a cavalryman in Capt. Gilbert Livingston’s Troop of Benedict Arnold’s American Legion. One Jacob Defendorff, who was probably his son, enlisted in the same troop four days later. Jacob, who had been sick on Long Island, disappears from the rolls as of May 1. Henry disappears from the rolls as of January 15, 1782.[23]

Meanwhile, on November 8, 1782, Maj. Gen. William Heath reported from Continental Village (located just north of New York City, near Peekskill) to New York Governor George Clinton at Poughkeepsie that:

I forward, one Henry Defendorff, who left New York the night before last with three others, and arrived Wed here the last evening. Defendorff is a very intelligent man, says he was a lieutenant in the Third New York Regiment, retired as Supernumery, was taken at Newark and with his wife and Child carried to New York, where he inlisted into Arnold’s Corps with a view to get his Liberty the first opportunity that offered,— his wife and child are down at Niack with the water Guard. Your Excellency who probably knows his Character will best know how he is to be treated. Defendorff has been employed in a way, that has given him an opportunity of knowing the situation of the Enemy as well as any man I have seen, and can give you many particulars.[24]

The night before, General Heath had written in his own journal about how the two deserters who had arrived at Continental Village (which were logically the common deserters Henry and Jacob Defendorff), had made their escape:

Two deserters came in from New York; they left the city the evening before—they were very intelligent; by them it was learnt that the British fleet returned to Sandy Hook the preceding Saturday was a week—that no action happened while they were at sea—that the troops were disembarked from the men-of-war, but remained on board the transports—that Gen. Sir Henry Clinton landed on Long Island and came across to the city.[25]

The phrase “very intelligent man” indicated the man was in possession of valuable military intelligence. Since Defendorff had made his newest home in the New Jersey town next to Sandy Hook and served with the British, he would be able to provide a lot of information. It also bodes the question, had Defendorff moved way down there for other reasons than personal preference? Perhaps he was watching the British fleet? Also, what was he doing in Newark that got him arrested?

Nevertheless, there was sufficient information provided to prompt Governor Clinton to send a letter back to General Heath on November 10, 1781, that he had consigned Defendorff to the Committee of Conspiracies and presumed they would permit him “to take his Family to Schenectady where his Relations reside & his political Character can be better ascertained than at this place.”[26]

If Defendorff’s family (his own or his in-laws) was from Schenectady, New York, this could explain why he was there to confront Captain Bloomfield’s attackers outside of Albany. Yates’s company of the 2nd New York of 1775 was geographically recruited from Tryon County, but Schenectady was relatively close to the county line. It is also only about fifteen miles west of Albany. So, he could have been in transit between locations when Bloomfield was confronted. Then again, being familiar with the area, he could have been there for other reasons.

There is no known record of what service Henry Defendorff provided after being handed over to the Committee of Conspiracies. He was awarded New York State bounty land of two 600-acre lots in Onondaga County, New York, on July 9, 1790. As a resident of Dover, Delaware, he arranged to transfer what might have been the awarded two lots of land, to two individuals, in 1793. He also tried to transfer the land to a third party, claiming he had not previously sold the land.[27]

It is very frustrating to come to the end of this narrative and have no definitive conclusion. The facts presented show Henry Defendorff to be a sound and reliable officer who served with distinction. Any other conclusions that might be drawn from this narrative are purely speculative. They do give one pause to think of the intriguing possibility that, for much of the war, Henry Deffendorf may have been involved with intelligence-gathering, conveying information, or other forms of espionage.

[1] Muster Roll of Captain Christopher P. Yates’s Company of the Second Regiment of New York Troops now in the Service of the United Colonies, August 29, 1775, Revolutionary War Rolls 1775-1783, War Department Collection of Revolutionary War Records, Records Group 93 (Washington: National Archives Microfilm Publications, M246), Roll 67, Jacket 19. Berthold Fernow, ed., Documents Relating to the Colonial History of the State of New York (Albany, NY: Weed, Parsons and Co., 1853–1887), 15:528&549. Defendorff is often confused with Capt. Henery Diefendorf of the Tryon County (NY) Militia who was killed at the Battle of Oriskany in 1777. For example, see Frances B. Heitman, Historical Register of Officers of the Continental Army During the War of the Revolution, April, 1775, to December, 1783, Reprint of the New, Revised, and Enlarged Edition of 1914, With Addenda by Robert H. Kelby, 1932 (Baltimore MD: Genealogical Publishing company, 1982), 197, where the service records of both men were incorrectly fused into one entry.

[2] Pension application depositions of various members of Captain Yates’s company of the 2nd New York Regiment, 1775, (National Archives Microfilm Publication M804, John Anthony (S.44589 Roll 68), Philip Deharsh (S.13293 Roll 1207), Andrew Fine (S.43561 Roll 975), Daniel Hart (S.13293 Roll 1207), Jacob Pealer (S.44241 Roll 1894)), Revolutionary War Pension and Bounty Land Warrant Application Files, 1800-1900, Record Group 15, National Archives Building, Washington, DC. There is no known official record of this change over of command, but these federal pensioners all describe continuing in the service with Andrew Finck to finish out 1775.

[3] Entry for Henry Dieffendorf, Heitman, Historical Register of Officers, 197.

[4] Ibid. Muster Roll of Captain Andrew Finck’s Company in Colonel Van Schaick’s Battalion of Forces…, February 16 to December 17, 1776, Revolutionary War Rolls 1775-1783, Roll 77, Jacket 163. The roll lists him as a 1st lieutenant and joining the battalion on February 16. It also states he was on furlough in Albany. The dates of this furlough are not given, so it could have been for all eleven months. It also does not list his promotion from 2nd lieutenant, so the muster roll had to have been rewritten after July 1776 or he actually started out with the battalion as 1st lieutenant in February.

[5] Mark E. Lender and James K. Martin, editors, Citizen Soldier: The Revolutionary War Journal of Joseph Bloomfleld (Newark, NJ: New Jersey Historical Society, 1982), 56.

[6] Samuel Stringer to Maj. Gen. Horatio Gates, July 24, 1776, Peter Force, ed., American Archives (Washington, D.C., 1837-53), 5th Series, 1:651-652. Fort George, which was never completed, was built on the site of the 1755 Battle of Lake George at the southeastern end of Lake George.

[7] Arrangement of Officers of Colonel Van Schaick’s Regiment, endorsed 1776, Calendar of Historical Manuscripts Relating to the War of the Revolution, in the Office of the Secretary of State (Albany, N.Y.: Weed, Parsons and Company, 1898), 2:45.

[8] James Cuyler to James Duane. December 9, 1776. Force, American Archives, 5th Series, 3:1129. Calendar, 2:21.

[9] Fernow, Documents, 15:77, 527. Muster Roll of the Field, Staff and Other Commissioned Officers in Colonel Goose Van Schaick’s Battalion…, December 17, 1776, Revolutionary War Rolls 1775-1783, War Department Collection of Revolutionary War Records, Records Group 93 (Washington: National Archives Microfilm Publications, M246), Roll 77, Jacket 163. Entry for Peter Yates, Heitman, Historical Register of Officers, 609. Colonel Yates was actually the father of Defendorff’s old captain in 1775, Christopher P. Yates. If this is any measure, it should be noted that Yates was the lieutenant colonel of three different New York continental regiments within a twelve month period from 1775 – 1776.

[10] Minutes of Courtmartial at Fort Ticonderoga 26-28 October1775, Philip Van Cortlandt – President, Fort Ticonderoga Museum, Thompson-Pell Research Center, M2064. Captain Pratt was found not guilty and discharged from arrest.

[11] Letter from Goose Van Schaick, December 23, 1776, Journals of the Provincial Congress, Provincial Convention, Committee of Safety and Council of Safety of the State of New-York: 1775-1775-1777 (Albany, NY: Thurlow Weed, 1842), 2:261.

[12] Fernow, Documents, 15:174, 197.

[13] Journal of the most Material Occurrences preceding the Siege of Fort Schuyler (formerly Fort Stanwix) with an Account of that Siege, etc., undated manuscript, attributed to William Colbreath, The Rosenbach of the Free Library of Philadelphia, AMs 1083/27. Published on-line by Schenectady County Public Library,

http://www.schenectadyhistory.org/resources/mvgw/history/064.html.

[14] Ibid. Manuscript by Lt. Col. Marinus Willett, August 11, 1777, Hero of Fort Schuyler: Selected Revolutionary War Correspondence of Brigadier General of Peter Gansevoort, Jr., David A. Ranzan and Matthew J. Hollis, editors, (Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, Publishers, 2014), 77-79. This manuscript does not otherwise mention Defendorff, so he probably did not take part in the sortie. Entry for Henry Defendorff, New York State Society of the Cincinnati: Biographies of Original Members & Other Continental Officers, Francis J. Sypher, Jr. (Fishkill, NY: New York State Society of the Cincinnati, 2004), 116-119.

[15] New York in the Revolution as Colony and State, James A. Roberts, Comptroller, (Albany, N.Y: J. B .Lyon Company, Printers, 1904), 1:facing page 120. Entry for Peter Gansevoort, Heitman, Historical Register of Officers, 242. The letter was to congratulate Gansevoort for his promotion brigadier general. This was a misunderstanding as the New York Continental Line already had a brigadier. Continental Congress had appointed Gansevoort the “Colonel-Commandant of the Fort so gallantly defended” on October 4, 1777. He became brigadier general of the Albany County Militia in 1781.

[16] Muster Rolls of the Field, Staff and Other Commissioned Officers in the 3rd New York Battalion…, October 3, 1777 – April 14, 1778, Revolutionary War Rolls 1775-1783, Roll 69, Jacket 40. 1st Lieutenant Defendorff is first listed as recruiting duty by order of Major Cochran, until November 1, 1777. He is later listed as resigning on that date “by leave of Col. Gansevoort.”

[17] Muster Roll of Captain Elias Van Benschoten’s Company in the Third Battalion of New York Forces…, April 14–May 29, 1778, Revolutionary War Rolls 1775-1783, Roll 70, Jacket 49.

[18] Fernow, Documents, 15:197.

[19] Muster Roll of the Field, Staff and Other Commissioned Officers in the 3rd New York Battalion…, March 6, 1778 – April 14, 1778, Revolutionary War Rolls 1775-1783, Roll 69, Jacket 40. Deposition of John Ball, July 27, 1832, Pensions (W.5767, Roll 127).

[20] Resolution of the Continental Congress, November 24, 1778, Worthington C. Ford, ed., Journals of the Continental Congress, 1774-1789 (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1908), 12:1156.

[21] Muster Roll of the Field, Staff and Other Commissioned Officers in the 3rd New York Battalion…, October 3, 1777 – January 19, 1778, Revolutionary War Rolls 1775-1783, Roll 69, Jacket 40.

[22] Entry for Henry Defendorff, New York State Society of the Cincinnati, 116-119.

[23] Ibid. Todd W. Braisted, personal communications, March 31 and July 9, 2015. Library and Archives Canada, RG 8, “C” Series, 1871:2.

[24] Maj. Gen. William Heath to Governor George Clinton, November 8, 1781, Public Papers of George Clinton, First Governor of New York, 1777-1795, 1801-1804, Published by the State of New York (Albany, NY: Oliver A. Quale, 1904), 7:494-495.

[25] Entry for November 7, 1781, Memoirs of Major-General William Heath by Himself (New York, NY: William Abbatt, 1901), 297-298.

[26] Governor Clinton to General Heath, November 10, 1781, Papers of George Clinton, 7:495. The full title of this body was “The Committee of the Convention of the State of New York for Enquiring into, Defeating and Detecting all Conspiracies that may be formed in said State.” Appointed early in 1776, it was an enforcement arm of the political revolution that performed secret services and dealt with issues regarding Loyalists, restoring property wrongfully taken, running guns, guarding and escorting prisoners, etc. New York in the Revolution as Colony and State, Supplement, Frederic G. Mather, ed. (Albany, N.Y: O.A. Quayle, 1901), 227.

[27] Entry for Henry Defendorff, New York State Society of the Cincinnati, 116-119.

12 Comments

A very interesting saga which demonstrates the complexities of the period! The unknown possibilities are tantalizing. Makes me want to share a pint of ale with Denfendorff at his favorite tavern to hear the rest of the story!

Thanks so much Gene. I totally agree. That is why I love soldier’s stories so much. They fought on either side of the Revolution, but these individual heroes seem to be rarely celebrated in the printed word. The information is not easy to find, but we need more of it brought to public view. I have vowed to do my share. I hope others will join in (if they have not done so already).

To my regret Defendorff was not destitute enough or lived long enough to file a federal pension application or we might have learned so much more. The New York State Society of Cincinnati did yeoman’s work on much of his biography. Yet, according to the Society’s website, though eligible, neither Defendorff, his son, nor any descendants (if there were any) ever became a member of the Society.

Wow! Finally. A piece based upon primary source information versus a mish-mash of selected works written by other historians. Well done!

Ken, I am so glad you liked the article and the primary research behind it.

Your comment brings to mind a line on a Murphy’s Law calendar that I had on my desk many years ago: “History doesn’t repeat itself. Historians mearly repeat each other.”

Please check out my other JAR articles. Those and some others I have written can also be found on Continental Consulting’s website (www.conconsul.com/writer.html).

Phil, this was a wonderfully assembled piece of work. As someone who has tried to research the progeny of this individual for over 25 years, I salute your efforts to provide a very detailed and objective historical analysis. The article was also timely, as I was doing a web search on Henry and it brought me to this wonderful Journal to which I am now a subscriber.

By the way, the timeline indicated for Henry and his son Jacob and the apparent geographic proximity of their family to the other Mohawk Valley Diefendorf’s strongly suggests that he may have been one to the missing siblings of Capt. Jacob Diefendorf, the son of Johannes Dubendorffer, one of two progenitors of the NY families. Capt. Henry Diefendorf, whom you indicated was often confused with Lt .Henry, and who died at Oriskany, was the son of the other NY Progenitor, Heinrich Dubendorffer. The cousins, Capt. Jacob and Capt. Henry, were both born in 1740.

Thank you so much, Drew. In reading your brief comments, one can easily see just how confusing it all is. I thank you for providing this information and will definitely save it for future use.

Phil:

Outstanding job! Nice to see such detailed research. Keep ’em coming!

By studying Defendoff one can really see how messed up the command was with decision making.Had to attempt to read it the second time.At least some one takes the time to try and put this part of history together,thanks Phil.

Thanks for a wonderful article. Two of my fellow Defendorff/Diefendorf family have been diligently trying to get the DAR to accept their work on Henry, so far to no avail.

Your work makes me think of the current ongoing show TURN Washington’s Spies – Henry’s work sounds very much like what is going on in that show, and in the exact same area!

Thanks for your contributions! Patti Andrews

Thank you so much Patti. Your family members might try getting membership in the Society of Cincinnati. There appears to be a opening there, as he or his descendants never applied for membership. As for TURN, I do hope my work is documented a “wee-bit” better than what was presented in that TV series. It seems that Hollywood still will not let history get in the way of a fictionalized story. Oh well, “it is what it is,” and it only encourages me to keep up the good fight to prove them wrong. In fact, I have a little something in the works right now. As usual it is proving to be more difficult to put together than I originally imagined.

Phil, I’m one of the researchers Patti mentioned. Good to meet you at the Rev. War Conference. Thank you for the great citation of sources in your article. From them I’ve been able to continue some good research

Phil,

This article just busted open a years-old mystery I have been trying to solve! I am a descendant of Capt. Joel Pratt and have been researching for some time (with no luck until now) the reason for a 1775 Fort George muster roll notation of “under arrest” next to Pratt’s name. I had actually come to the conclusion a while back that the note was actually intended for Pratt’s first lieutenant, Benjamin Chittenden, who had gotten into some trouble for raiding a house of its weapons. The home owner filed a complaint with the Albany County Committee of Correspondence and they were not pleased with Chittenden’s actions.

Your brief mention of Pratt’s unsuccessful court martial attempt by Lt. Col. Peter Yates left me in a state of shock! I have since contacted the museum at Ft. Ticonderoga and they have sent me the court martial documents. Thank you for opening up a HUGE door in my own family research!

-Ryan McGuire