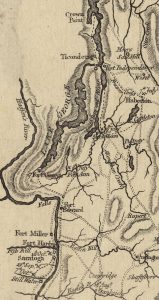

Burgoyne’s campaign of 1777 has been termed a turning point in the American Revolution.[1] Marked by the Continental Army’s victories at the battles of Bennington and Saratoga, the campaign came to show the limits of the British army and gave credence to and international recognition of the American cause. Hidden in these histories of Burgoyne’s campaign is the role two days of fighting near Fort Anne had in shaping the later campaign. On July 7 and 8, 1777, remnants of the Continental forces retreating from Fort Ticonderoga and Skenesborough along with members of the Albany Militia engaged the British 9th Regiment of Foot on what is now known as Battle Hill outside of the village of Fort Ann, New York.[2] On the steep slopes of Battle Hill, the Continental Army fought for two main reasons: to stall the British army’s advance and to regain confidence after a series of devastating losses.

The events leading to Fort Anne began on the night of July 5, 1777. With the positioning of British artillery atop Mount Defiance, Continental Maj. Gen. Arthur St. Clair saw his army’s defense of Fort Ticonderoga as untenable.[3] He planned to secret his army out of Fort Ticonderoga. While he led his main army of about 2,000 troops east towards Hubbardton, a small contingent of women and sick and wounded soldiers under the guard of Col. Pierse Long’s New Hampshire Regiment traveled south on bateau to Skenesborough (present day Whitehall, New York).[4] Long’s flotilla made its way to Skenesborough, but was followed within hours by Burgoyne’s fleet.[5] Burgoyne’s ships fired on Long’s flotilla while the 9th, 20th, and 21st Regiments took to the land to outflank the Continentals. Even after joining Scammell’s Company of the 3rd New Hampshire Regiment at Skenesborough, Long’s forces were unable to make a stand against the British. As Continental Army surgeon James Thacher described it, “The officers of our guard now attempted to rally the men and form them in battle array; but this was found impossible, every effort proved unavailing, and in the utmost panic, they were seen to fly in every direction for personal safety.”[6] In the confusion, the Continentals abandoned Skenesborough along with most of their supplies and personal belongings.

The Continentals continued their retreat along Wood Creek towards the Continental outpost at Fort Anne. The women, sick, and injured from Fort Ticonderoga floated south along Wood Creek, while soldiers continued along the military road and woods that paralleled the attempting to stop or slow any advance from the pursuing British. Close behind the evacuees was a contingent of 190 British soldiers from the 9th Regiment of Foot under the command of Col. John Hill.[7] At some point during journey between Skenesborough and Fort Anne, the British overtook some of the bateau taking approximately thirty prisoners.[8] Unable to stop the capture, the Continentals continued on to Fort Anne.[9] After almost two continuous days of retreating, Long’s group arrived at Fort Anne in the early hours of July 7. The motley force of Continentals, now joined with the 15th Massachusetts under Capt. Benjamin Farnum, [10] decided to make a stand against Burgoyne’s army. As Col. Jonathan Trumbull stated, “Genll Schuyler with the little handful of fugitives from Ty. and the small body of militia already collected, is forming his stand at Fort Ann where they are in want of everything that can be conceived necessary for the subsistence of an Army.”[11] Capt, James Gray of Scammell’s Company of the 3rd New Hampshire and his rear guard were the last to arrive at Fort Anne at about 6 o’clock on the morning of July 7.[12] He would have little time to rest before setting out again.

Captain Gray’s company was back in the field around 11 A.M. leading a force of 150 soldiers and 17 rangers towards the British.[13] In the early hours of July 7, Colonel Hill and his troops encamped at the base of a hill north of Fort Anne to observe the Continentals.[14] With the British encampment as their goal, Gray’s troops crossed wetlands and woods for approximately a half mile before dividing his troops to outflank the British.[15] Hill’s troops realized their precarious position and withdrew up the hill behind them. Gray’s men followed taking position at the base of the hill. The fighting continued throughout the day. Neither side was able to get an advantage over the other. At some point during the fighting, 150 troops from Fort Anne reinforced Gray’s soldiers. Around 6 P.M., Gray’s Continentals withdrew from Battle Hill, returning to Fort Anne. The Continentals suffered one killed and three wounded, while the British suffered three soldiers killed.[16] By bringing the fight to the British, Gray prevented a siege of Fort Anne and made the fight a conflict over Battle Hill.

During the night of July 7, both sides regrouped and prepared for the next day’s fight. The British established a new camp along the southern base of Battle Hill. This position was unobservable from Fort Anne and easier to defend with the hill in the 9th Regiment’s rear and Wood Creek at its front. The Continentals at Fort Anne welcomed reinforcements from the Albany Militia’s 6th Regiment under the command of Col.onel Henry K. Van Rensselaer along with orders from Maj. Gen. Philip Schuyler. While St. Claire’s army was retreating from Fort Ticonderoga, Schuyler was enacting a plan to delay Burgoyne’s Army.[17] With much of the Northern Department in disarray following Fort Ticonderoga, Schuyler needed time to reorganize his troops and the local militia to make a stand against Burgoyne. By delaying Burgoyne’s advance, Schuyler gained time to remove supplies and personnel from Fort George and Fort Anne and centralized his forces at Fort Edward and later Stillwater.[18] A delay also gave Schuyler time to obstruct water routes and destroy roads, further slowing Burgoyne’s progress. Fort Anne provided a means to create this delay.

On the morning of July 8, a deserter from the Continental Army entered the British camp. The deserter informed Colonel Hill that the Continental forces at Fort Anne numbered about 1,000 troops.[19] The actual number was about 700 Continental and militia troops.[20] With only 190 soldiers, Colonel Hill new he could not overtake the Continentals and asked Burgoyne for reinforcements. Shortly afterwards, the deserter vanished from the camp. The British quickly realized he was a spy sent to determine the number of British soldiers.[21] Burgoyne was unable to comply with Hill’s request as most of Burgoyne’s army was busy transporting artillery and baggage over the falls at Skenesborough to prepare for his land invasion.[22] Eventually, Burgoyne ordered the 20th and 21st Regiments of Foot to reinforce the 9th Regiment at Fort Anne. However, they were stalled by a rain storm. Colonel Hill’s 9th Regiment was on their own to stop the Continentals.

With the arrival of the Albany Militia, Colonel Long was ready to continue his attack on the British position. Captain Gray’s troops encroached on the British encampment supported later by the Albany Militia.[23] The British sentries initially repelled the Continentals, but were eventually overcome.[24] The militia passed along the southern bank of Wood Creek before crossing the creek and taking position on the British left. The British army’s new encampment offered protection; however, the thick woods surrounding the encampment worked better at concealing the advancing Continentals. The British could hear, but not see their enemy. With Gray’s troops on their right, the Albany Militia on their left, and Wood Creek in front, the British had no choice but to retreat up the hill behind them.[25]

The British withdrawal up the hill was a running firefight. Several British soldiers were killed or wounded during the retreat. British Capt. William Montgomery was mortally wounded near the start of the withdrawal. As the Continentals overcame the British camp, they found Capt. Montgomery along with the 9th Regiment’s surgeon who stayed to care for the captain.[26] They also discovered the women, injured, and sick evacuees who the British took as prisoners on Wood Creek during the Continental retreat to Fort Anne. The freed prisoners, Captain Montgomery, and the surgeon were sent to Fort Anne for the duration of the battle. The Continentals continued their pursuit of the British up the hill. During this advance, the Albany Militia’s commander, Colonel Van Rensselaer, was shot in the upper thigh.[27] His troops, thinking it was a mortal wound, pled for him to return to the fort. Instead, he remained on the battlefield as the fight continued. Despite the intense fire, the British 9th Regiment reached the top of the hill.

Atop the hill, the British adopted some creative tactics to defend their position. To defend against the Continental troops completely surrounding them and overcoming their position on the ridge top, the British used a single file formation stretching the British line across the main ridge. This formation differed from the two rank formation usually used by the British army in America.[28] Another unconventional method the British used was in the way they loaded their muskets. British Private Roger Lamb claimed that the troops were quickly loading their muskets by striking the “breech of the firelock to the ground” rather than using the ramrods.[29] British officers were against such loading technique since it often resulted in misfires. Lamb admitted this method may have led to a fellow soldier’s musket exploding next to him.[30] However, the British soldiers felt compelled to use it in response to fighting in areas with thick woods and concealed Continental soldiers.

The British and Continentals continued their firefight throughout the afternoon. The hill’s terrain prevented either side from achieving an advantage. The British position atop the hill allowed them to fire onto the Continentals, but the slope and terrain obstructed their view of the Continental positions. The terrain concealed the Continentals, but also prevented them from reaching the British on top of the hill. The result was a stalemate that stretched the battle into the afternoon.

With both sides running low on ammunition, the Continentals started to make a final push to overcome the British position. They were halted by the sound of a war whoop.[31] Burgoyne was unable to send full reinforcements to help the 9th Regiment, but Burgoyne’s quartermaster, Capt. John Money, and a group of allied Native Americans arrived to help the 9th Regiment. Despite Money’s orders, his allied Native Americans decided not to join the battle and withdrew, leaving Money alone. Unable to properly reinforce the British, Money let out a loud war whoop. With ammunition running low and unable to determine if the source of the whoop was a British reinforcement, the Continentals retreated from the hill back to Fort Anne.

Colonel Long held a council of war at Fort Anne to determine his next steps. Low on supplies and successful in delaying the British advance, Long decided to abandon Fort Anne and withdraw to Fort Edward.[32] Long’s forces burned Fort Anne and its associated buildings, but in his rush to leave, left the sawmill and blockhouse at nearby Kane’s Falls intact.[33] The Continentals suffered fifteen soldiers killed and wounded, and captured three or four prisoners.[34] Burgoyne stated that the British captured thirty prisoners, provisions, and the 2nd New Hampshire regimental colors.[35] These prisoners may have been the sick or wounded who were unable to continue to Fort Edward. The official British record of loss listed thirteen killed, twenty-two wounded, and two captured at the Battle of Fort Anne.[36]

The Continental army’s withdrawal from Fort Anne to Fort Edward was difficult. The Continentals began their march at 3 P.M. and arrived at Fort Edward at 10 P.M. on July 8.[37] Following the recent events, most of the Continental soldiers had no baggage or supplies. With no barracks or food to spare at Fort Edward, most of those who fought at Fort Anne ended up sleeping on the open ground with no blankets during a rain storm.[38]

Burgoyne slowly marched the rest of his army to Fort Anne. Even with the withdrawal of the Continental Army, Burgoyne did not establish his campaign headquarters at Fort Anne until July 22.[39] By July 28, the main army began to march from Fort Anne leaving soldiers to help with supplies.[40] In his journal, Burgoyne stated that his goal turned to defeating the large army of Continentals amassed at Fort Edward.[41] The British Army’s opening of roads and clearing of creeks allowed for the movement of baggage, artillery, and provisions. As he moved along the land route to the Hudson River and continued his advance, the opening of these routes became increasingly important to ensure the continued supply of his army. He also ordered his troops to move his gun boats and supplies from Fort Ticonderoga towards Lake George.[42] His plan was to have his forces march from Fort Anne and Lake George, converging on Fort Edward. If successful, he could decimate the Continental Army’s Northern Department. It also dedicated him to a path made more difficult with the requirement of investing in repairing or building roads, and moving provisions and artillery across a wilderness terrain.

In Burgoyne’s proposal he acknowledged the logistical weakness of his plan: “… the route by South Bay and Skenesborough may be attempted, but considerable difficulties may be expected, as the narrow parts of the river may be easily chocked up and rendered impassible, and at best there will be necessity for a great deal of land carriage for the artillery, provisions, etc. which can only be supplied from Canada.”[43] Schuyler tried his best to make this a reality. With Colonel Long’s successful delaying action at Fort Anne, Schuyler was able to remove personnel and resources from outlying forts such as Fort George, and concentrate his forces at Fort Edward in preparation of Burgoyne’s advance. He also set up obstacles for Burgoyne’s army by destroying bridges and felling trees into waterways. Rather than continue his steady advance, Burgoyne was forced to clear and cut roads and remove Schuyler’s obstacles, thus slowing his advance along the Hudson River Valley.

By September of 1777, Burgoyne’s campaign began to falter. He was unable to replenish his lost troops and the Loyalist forces he thought would join him never emerged. That September, Burgoyne ordered the abandonment of Fort Anne as he was unable to defend the post against Continental raids.[44] Continental soldiers quickly reestablished control of Fort Anne and used it to undermine Burgoyne’s supply chain. Although he spent July and August trying to ensure his supply lines, the long distance between Canada and his army led to gaps and opportunities for the Continental Army to attack it. The Continentals increasingly surrounded his forces. With his losses of soldiers at Freeman’s Farm and Bennington, and defeat at Bemis Heights, along with the death of his leading officer, Brig. Gen. Simon Fraser, Burgoyne found few options for victory. He surrendered to Continental Maj. Gen. Horatio Gates at Saratoga on October 16, 1777.[45] The fight between two small contingents of much larger armies over those two days at Fort Anne may have seemed like small skirmishes. However, they led to a series of events that not only changed American morale but also led to the failure of Burgoyne’s campaign.

Acknowledgements: This material is based upon work assisted by a grant from the Department of the Interior, National Park Service. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Department of Interior. I would also like to thank the NPS’s American Battlefield Protection Program and American Legion Raymond W. Harvey Post in Fort Ann for their support of our research as part of this grant.

[1] Richard Ketchum, Saratoga: Turning Point of America’s Revolutionary War (New York: Henry Holt and Company, 1997); John Luzader, Saratoga: A Military History of the Decisive Campaign of the American Revolution (New York: Savas Beatie, 2010).

[2] Michael Jacobson, Fort Anne: Historical Research and Archaeological Investigations of Battle Hill Battlefield GA-2287-13-012 (Binghamton, NY: Public Archaeology Facility, 2015); Eric Schnitzer, The Battles of Fort Anne, 7 and 8 July 1777 (Historical Summary, Stillwater, NY: Saratoga NHP, 2012).

[3] “Proceedings of a General Court Martial, &c.,” Collections of the New-York Historical Society for the year 1880, the John Watts De Peyster Publication Fund Series, Volume XIII (New York, Printed for the Society, 1881), 33-34; James Thacher, Military Journal of the American Revolution (Hartford, CT: Hurlbut, Williams, and Company 1823), 98-99.

[4] Bruce Venter, The Battle of Hubbardton (Charleston SC: The History Press, 2015), 34-35; James Thacher, Military Journal of the American Revolution (Hartford, CT: Hurlbut, Williams, and Company, 1823), 99.

[5] John Burgoyne, A State of the Expedition from Canada, as Laid Before the House of Commons by Lieutenant-General Burgoyne (London, UK: J. Almon, 1780), Appendix XVI-XVII; Thacher. Military Journal,100

[6] Thacher, Military Journal, 100.

[7] Burgoyne, A State of the Expedition, Appendix XVIII; Don N. Hagist, A British Soldier’s Story: Roger Lamb’s Narrative of the American Revolution (Baraboo, WI: Ballindalloch Press, 2004), 39.

[8] Hagist, A British Soldier’s Story, 39

[9] Capt. John Calfe account in Harriette Noyes, A Memorial History of Hampstead, New Hampshire (Boston, MA: George B. Reed, 1899), 290; William Weeden, ed., Diary of Enos Hitchcock, D.D., A Chaplain in the Revolutionary War (Providence, RI: Rhode Island Historical Society, 1899), 117.

[10] Benjamin Farnum, Benjamin Farnum Diary (Boston, MA: Massachussettes Historical Society, 1777), July 6.

[11] Jonathan Trumbull Sr. to George Washington, July 14, 1777, George Washington Papers.

[12] James Gray, Journal of march to Ticonderoga and the retreat to Skenesborough (now Whitehall), NY, 6-14 July 1777 (Boston, MA: Massachusetts Historical Society 1777), July 7.

[13] Ibid.

[14] Hagist, A British Soldier’s Story, 39.

[15] Gray, Journal, July 7.

[16] Gray, Journal, July 7; Noyes, A Memorial History of Hampstead, 290; Hagist, A British Soldier’s Story, 39.

[17] Farnum, Benjamin Farnum Diary, July 3; Pension depositions of James Hogeboom, William Miller, Jacob Van Alstyne, Widow of Henry Van Rennsselaer, and Abraham Wittbeck, National Archives, Washington, D.C.

[18] Ibid.

[19] Hagist, A British Soldier’s Story, 39.

[20] Gray, Journal, July 8; pension deposition of Henry Van Rensselaer.

[21] Hagist, A British Soldier’s Story, 39.

[22] Burgoyne, A State of the Expedition, Appendix XVIII-XIX.

[23] Gray, Journal, July 8.

[24] Hagist, A British Soldier’s Story, 39.

[25] Burgoyne, A State of the Expedition, Appendix XIX.

[26] Gray, Journal, July 8; Hagist A British Soldier’s Story, 40.

[27] Pension deposition of Henry Van Rensselaer.

[28] Matthew Spring, With Zeal and With Bayonets Only: The British Army on Campaign in North America, 1775-1783 (Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press, 2008), 142.

[29] Hagist, A British Soldier’s Story, 37.

[30] Ibid.

[31] Hagist, A British Soldier’s Story, 40.

[32] Gray, Journal, July 8.

[33] Burgoyne, A State of the Expedition, Appendix XIX.

[34] Governeur Morris to Provincial Congress July 14, 1777, Journal of the Council of Safety.

[35] Burgoyne, A State of the Expedition, Appendix XIX.

[36] British Colonial Office Records- Canada 1700-1922. CO42-36, 37 (Ottawa, ON: Library and Archives Canada), 36:709.

[37] Gray, Journal, July 8.

[38] Ibid.

[39] Burgoyne, A State of the Expedition, Appendix 42; James Phinney Baxter, The British Invasion from the North. The Campaigns of Generals Carleton and Burgoyne from Canada 1776-1777 with the Journal of Lieut. William Digby. (Albany, NY: Joel Munsell’s Sons, 1887), 233; James Hadden, A Journal Kept in Canada and Upon Burgoyne’s Campaign in 1776 and 1777 by Lieut. James M. Haddden (Albany, NY: Joel Munsell’s Sons, 1884), 96.

[40] Baxter, Journal of Lieut. William Digby, 239; Hadden Lieut. James M. Hadden Journal, 98.

[41] Burgoyne, A State of the Expedition, Appendix XIX.

[42] Ibid.

[43] Burgoyne, 1777, in Douglas Cubbison, Douglas Burgoyne and the Saratoga Campaign: His Papers (Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press, 2012), 183.

[44] Hadden, Journal, lxxxiii-lxxxiv.

[45] Ketchum, Saratoga, 425.

7 Comments

Informative piece on a little known action but I’m curious as to why you don’t consider the Battle of Hubbardton on July 7 to be the first stand by the Continentals?

Some folks probably do not know that the Civil War Trust through its Campaign 1776 arm is trying to buy the Fort Anne battlefield.

A very interesting article illuminating an oft overlooked aspect of the 1777 British invasion. Too often, we focus on the climatic battle at Saratoga and don’t tell the story of the depletion of British combat power at Hubbardton, Bennington, Fort Ann and throughout the march to Bemis Heights. Further, Burgoyne thought that the fall of Fort Ti was seminal and that he had defeated the Patriots. As a result, he grossly underestimated the resolve and fighting capacity of the forces he was going to face.

The battlefield is a beautiful spot today and I hope that Civil War Trust is able to secure title and preserve its character. It would be a great spot for an interpretive center for the Wood Creek corridor and its rich history.

Very well written! Join us in Fort Anne for a marker dedication May 10th, 2017!

I have to stand with Mike Barbieri regarding Hubbardton. There were several Continental regiments represented at Hubbardton. Plus all three senior leaders, Col. Seth Warner, Col. Ebenezer Francis (KIA) and Col.Nathan Hale (POW) were Continental officers. That said, it is great to see a light shined on the battle of Fort Ann because it is a neglected engagement in Burgoyne’s campaign. And this battlefield should be preserved. Nice job and thanks, Mike.

so is it Ft. Ann or Anne?

The fort is Fort Anne, named for a queen of England. The town where it is located is, today, named Fort Ann. The reason for the different spelling of the town’s name is not clear.

For more: https://www.townoffortannny.com/what-happened-to-the-e.html