Though he was just twenty-two years of age, Walter Stirling already possessed enviable social advantages. He had powerful family connections and enormous personal wealth. A successful banker himself, his renowned father was on the verge of being raised to one of the most prestigious posts in the Royal Navy as Commander-in-Chief, The Nore.[1] If he was considered by many a boorish social climber, his connections, ambition and wealth were compensation enough to make him a much sought-after patron.[2] For those wishing admission to the exclusive court soirees and levees distracting London’s aristocracy during a long and failing war, his acquaintance was considered invaluable.

Yet even with his influence, the Philadelphia-born Stirling must have felt unusually apprehensive as he waited in line outside the Throne Room at St. James Palace to present his respects to King George III. For the man standing alongside him, dressed in the cochineal scarlet of a British general officer, was not just the husband of his cousin Peggy Shippen, but also the most notorious officer of the war, Benedict Arnold.[3]

Stirling’s fleeting anxieties about introducing such a pariah to his sovereign, however, were quickly appeased. George III, a stubborn but immensely faithful man, immediately took to both the “Loyalist” Arnold and his charming wife Peggy, whom he declared “the most beautiful woman he had ever seen.”[4] Though the British government had already amply rewarded his treachery, the King granted Arnold a gratuity of £500, while his enamoured consort Queen Charlotte awarded Peggy a further annuity of £100.[5] Through early 1782 George was often to be seen wandering the Royal Parks in deep conversation with Arnold and his Secretary of State Lord George Germaine, even commissioning a paper from him on his “Thoughts on the American War.”[6]

Though Arnold received only cordiality and favour from the King, he was not nearly so highly regarded by his subjects.[7] One morning George was strolling with Arnold when he spied his Aide-de-Camp Lord Balcarres.

“My Lord do you know General Arnold?”

Balcarres, a veteran of the American war, stiffened, drew himself to his full height and spluttered, “what Sire? Do you mean the traitor Arnold?!” He pointedly turned his back and retreated. Needless to say, the fiery and volatile Arnold regarded such a tart response as an unforgivable attack on his reputation, and a duel of honour was swiftly arranged.

On the prescribed morning Arnold stood just twelve paces from an adversary he had last faced amongst the wheat fields of Saratoga. At his second’s command, Arnold drew his pistol and fired, but wide. He stood, nervously awaiting Balcarres’s riposte, but it never came. The Earl turned on his heel and nonchalantly began to stroll away. Incensed at a further challenge to his honour Arnold called out,

“Sir will you give me no satisfaction?”

The Earl replied without breaking step, “Sir, I leave that task to the Devil.”

It is an excellent tale free from any moral ambiguity. Two heroic champions are thrown together on battlefield and duelling ground clean across two continents, both men the personification of loyalty and treachery, their lives fated to be entwined in a tragedy of Shakespearian proportions. There is only one inconvenient problem with this epic tale. It never happened.

It is not difficult to understand why this oft-reported story has been misrepresented in histories for nearly two hundred years and is regularly repeated today. Its first appearance was not until 1833, long after the death of both protagonists, in the book Three years in North America by James Stuart.[8] In many ways a gem of a book, this gossipy, opinionated travelogue is unfortunately wholly unreliable as a historical source. This has not stopped both American and British academics referencing it in varying guises ever since. Indeed so compelling is the tale even the current Earl Balcarres insists it to be fact.[9]

The Lord Balcarres was born into one of Scotland’s mightiest aristocratic Clans, the Lindsays, and after a first-class education in England and Germany he followed a long family tradition by joining the Army. By 1777 he was a major of in the army serving in a light infantry battlion in America, at the age of just twenty-five.[10] A down to earth, outspoken man with a tendency towards sarcasm, Balcarres proved to be an able and vigorous officer in action if a lazy and disinterested administrator.[11] Like Arnold, he possessed an almost demonic personal bravery. At the battle of Hubbardton, his clothing was shot through in thirteen different places, yet Balcarres suffered only a minor wound in the British victory. At Saratoga, only his foresight in engineering the formidable redoubt that still bears his name saved Burgoyne’s army from complete destruction.[12] It is not too fanciful to suppose that Arnold, whipping the troops of Enoch Poor’s Brigade Into a frenzy beneath the sharpened stakes at the base of this redoubt, must have been just yards from him.[13]

Though his prudence saved Burgoyne’s army from annihilation, it could not save it from defeat, and for two years he was a “Convention” prisoner in New England and Virginia.[14] On his return to Britain in 1779, he entered into manufacturing and helped establish the famous Haigh Ironworks in Lancashire, while all the time maintaining an active military career, first as commander in Gibraltar then as Lieutenant-Governor in Jamaica. There is no evidence that Balcarres ever met Arnold either as a prisoner in America or as a fellow officer in Great Britain.

As for Arnold, it is true that the pugnacious Connecticotian fought many duels before, during and after the war, and that one of them was against a Scottish Earl. However, that man was Lord Lauderdale, not Balcarres, whom Arnold believed, quite wrongly, had slighted him during a Parliamentary speech. Both men survived the duel.[15]

Though it was officially a secret, the affair was widely reported by the newspapers of the day and featured melodramatically in a letter Peggy sent back to her father in Philadelphia. “The time appointed was seven o clock the morning of Saturday last … It was agreed they should fire together which the General did without effect … Lord Lauderdale refused to fire.” She concluded rather too optimistically, “It has been highly gratifying to see the Generals conduct so much applauded.”[16] A voracious letter writer, she never again mentioned any past or extant duels in her correspondence, something her dramatic temperament would have been unlikely to have let pass without comment. In contrast, the supposed Balcarres duel is not reported in any contemporary newsprint or aristocratic correspondence. It’s details, however, bear a remarkable similarity to the contest involving Lauderdale.

In fact, despite the late eighteenth century being looked upon in popular imagination as an age of duelling, only a handful of well-documented cases concerning nobles took place during Arnold’s time in England. Had Arnold challenged an aristocrat like Lord Balcarres in the claustrophobic and febrile society of Georgian London, it would not have gone unnoticed.

Perhaps most damning of all, there is the unlikely circumstance that the insult was delivered in the direct presence of the King. Balcarres was never Aide-de-Camp to George III, and it is improbable that any respectable aristocrat would have snubbed an introduction from his sovereign in a way that placed him in such an invidious position. To have done so would have been more an insult to the King than to Arnold, and would have assuredly destroyed his career. There were many occasions when both Benedict and Peggy were slighted during their time in London, but strict social etiquette prevented any of them from being delivered in the presence of the Monarch.

What is left is undoubtedly more a parable than a historical narrative. It is hard not to suspect that it is still given credence today because so many long for it to be true. But false it assuredly is.

Nevertheless, there is some consolation for those who wish to study the associated lives of Arnold and Balcarres. If a close inspection of the duel’s circumstances exposes an account that cannot be verified, it unearths an even more tragic story that has passed by virtually unremarked.

Benedict Arnold’s eldest son, Benedict VI, did not share his father’s manufactured loyalty for the British; it was undoubtedly genuine. Like his father, he could be violent and headstrong, and twice he directly defied him by taking up a commission in the British army, even spending two years in France as a prisoner of war.[17] At twenty-seven as a captain in the Royal Artillery, he was assigned to the West Indies, where the British were having great trouble suppressing a rebellion of Maroons on the economically precious Island of Jamaica. The Jamaican Maroons were descendants of escaped African slaves who had formed independent free settlements in the Islands interior. For over fifty years they had been fighting a sporadic guerrilla war the British seemed incapable of quelling.[18] Attacking in well trained small bands from behind the rocks and dense undergrowth of the “cockpit” country, their hit and run tactics ground down and demoralised the completely unprepared British. In 1795 during one such maroon ambush, Benedict Arnold VI was mortally injured after a flesh wound in his leg turned gangrenous. Poignantly like his father at Saratoga, he stubbornly refused amputation of the limb, this time with tragically different consequences.

Back in England Benedict, already ailing with dropsy, received the devastating news of the loss of his son stoically but confessed, “his death is a very heavy stroke to me.”[19] He found some consolation when George Grenville, Earl Temple visited him in London and handed him his son’s sword and personal condolence letters, the latter affirming the regard and love Benedict VI had been held in by his fellow officers.[20] (25) Reading them, he must have also found solace in the detail that the general commanding the British forces in Jamaica had marked him out for commendation and future promotion.

That general, Benedict VI’s last commanding officer and would-be patron, was Alexander, 6th Earl of Balcarres.

[1] http://www.clanstirling.org/com.

[2] For an amusing if caustic assessment of Stirling from among others the future Prime Minister George Canning, see http://www.historyofparliamentonline.org/volume/1790-1820/member/stirling-walter-1758-1832

[3] Milton Lomask, “Benedict Arnold: the Aftermath of Treason,” American Heritage, October 1967, http://www.americanheritage.com/content/benedict-arnold-aftermath-treason?page=3

[4] Ibid.

[5] Charles Burr Todd, The Real Benedict Arnold (New York: A.S. Barnes, 1903), 22.

[6] Peter de Loriol, Famous and Infamous Londoners (Charleston, SC: The History Press, 2004), 31.

[7] For a contemporary assessment of Arnolds’ career that ends with a stinging and vitriolic conclusion, see The European Magazine and London Review, February 1783.

[8] James Stuart, Three Years in North America (Edinburgh: R. Cadell, 1833), 1:461.

[9] There are countless references to the supposed Balcarres-Arnold duel both online and in print many by sophisticated historians. None give reliable sources earlier than the James Stuart book. All have slightly different details but end with the same tag line of an irate and humiliated Arnold and a nonchalant and caustic Balcarres. Examples include:

“Today in history Alexander Lyndsey 6th Earl Balcarres passes away,” Masonry Today, http://www.masonrytoday.com/index.php?new_month=3&new_day=27&new_year=2016

- P. Kup, “Alexander Lindsay, 6th Earl of Balcarres, Lieutenant Governor of Jamaica 1794-1801,” Manchester University, www.escholar.manchester.ac.uk/api/datastream?publicationPid=uk-ac-man-scw:1m2767&datastreamId=POST-PEER-REVIEW-PUBLISHERS-DOCUMENT.PDF

“I’d rather take a bullet than apologize,” http://www.sorrywatch.com/2015/05/01/id-rather-take-a-bullet-than-apologize/Sorrywatch.com

The Scottish Nation: Balcarres, http://www.electricscotland.com/history/nation/balcaress.htm

Joe Craig, “Duel Personalities,” http://friendsofsaratogabattlefield.org/duel-personalities/

[10] Lord Lyndsay, Lives of the Lyndsays: A memoir (London: J. Murray, 1858), 343.

[11] F. Cundell, Lady Nugent’s Journal (London: West India Committee for the Institute of Jamaica, 1939), 18, 19, 22, 33.

[12] Nickerson Hoffman, The Turning Point of the Revolution (New York: Houghton Mifflin, 1928), 365. Hoffman also repeats the myth of the duel later in the book.

[13] John Luzeder, Saratoga, a Military History (New York: Savas Beattie, 2008), 289.

[14] Lyndsay, Lives of the Lyndsays, 344.

[15] Issac Newton-Arnold, Life of Benedict Arnold: His Patriotism and Treason (Chicago: Jansen Co., 1880), 367.

[16] Lomask, “Benedict Arnold.”

[17] Willard Sterne Randall, Benedict Arnold Patriot and Traitor (New York: William Morrow, 1990), Ch9.

[18] The Hon, John Fortescue, A history of the 17th Lancers (London: MacMillan Co., 1895), 73.

[19] Randall, Benedict Arnold Patriot and Traitor, Ch9.

[20] Ibid., v, though wrongly addressed as Grenville Temple.

4 Comments

Of course! Balcarres was the Governor of Jamaica! Wonderful, sadly ironic finale to a well-written piece.

It seems unlikely a duel of honor could have resulted from the alleged Balcarres – Arnold introduction by King George. Duels of honor were the antecedent to suits for slander and liable. Like those suits, honor is satisfied by truth.

Many thanks for correcting this error, which I repeated in the epilogue of my book, 1777: Tipping Point at Saratoga. I will make sure that it is corrected in future editions.

I read with great interest this article which brought new light on the alleged duel between Arnold and Alexander Lindsay. I have a particular interest in Lindsay because he fought at Hubbardton (his first action) during Burgoyne’s 1777 campaign. I appreciate the amount of effort John Knight put into dispelling the idea of Arnold and Lindsey dueling many years after the war. It was a very well-reasoned and well-researched argument. I really enjoyed it.

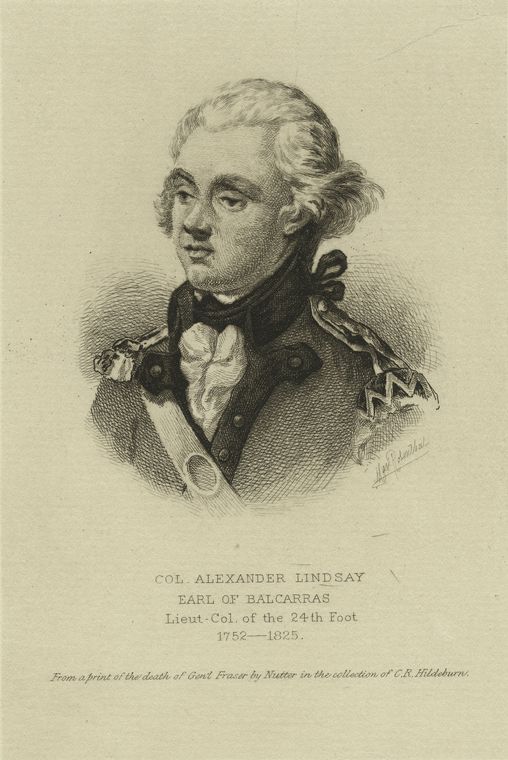

However, the second image displayed in the article was not Alexander Lindsay, 6th Earl of Balcarres. I have used this image myself and thought it was credible. But I recently showed my power point presentation on Hubbardton to Eric Schnitzer. He brought to my attention the error of my ways and thus the error in John’s article. Eric is the park historian at Saratoga National battlefield and an unqualified expert on every aspect of the 1777 campaign. If Eric had researched it, you can take it to the bank.

According to Eric, “the portrait of Lord Balcarres [in the JAR article] is actually that of one of Burgoyne’s ADC’s, Lt. Richard Wilford. I’ve done a lot of research on this particular misattribution. The picture in the 19th-century print, purported as Balcarres, was taken directly from Graham’s painting, The Burial of General Fraser (1794), and the figure represented in the painting was solidly identified as Wilford (Lord Balcarres doesn’t appear in the painting).”

The image I have provided here was sent to me by Eric. It is a portrait of Lord Balcarres, as Lt.Col. in the 2d Battalion, 71st Regiment of Foot, by an unknown artist, ca.1782.

Thank you, Bruce, (and Eric) for this splendid portrait of Balcarres. I have to say it was entirely unknown to me and it is a thrill to see so fine a picture of what is indisputably the Earl. The painting shows the Crawford/Balcarres nose, and as you say features him in the uniform of Simon Frasers Highland regiment. As it is in black and white, do I take it that the original is lost?

I will be in New York all Summer and I have not been up to Saratoga for some time. I would like to pass on my thanks to Eric in person if he is available. Are you the author of “The Battle of Hubbardton”?