Last month, Americans observed the peaceful transition of power from one president to another, from one political party to another. Some will point to a tradition that begins with George Washington, who voluntarily stepped down as the first president under the new U.S. Constitution when his second term ended. In fact, the new nation was familiar with peaceful political transitions. As colonists, citizens had experienced such change in English governments. As revolutionaries, their own governors had done the same while at war. Yet, in 1796 all eyes were fixed on Washington, who had dominated the political scene like no other and quite likely could have done so for the remainder of his mortal life.

For his part, the president had tired of public life, which offered constant strife and criticism. Moreover, his wealth and estates had suffered during his absence in the American Revolution, and again during his term as president. In 1792, Washington first considered retiring and invited James Madison to help him draft a farewell address, but tensions overseas, domestic instability, and his sense of duty led him to put off the decision. By the late winter of 1796, Washington was determined to go. In the intervening years, he had drifted away from Madison, who was in Thomas Jefferson’s camp as a critic of administration policy, and closer again to Alexander Hamilton, to whom he turned for his latest attempt at a farewell address.

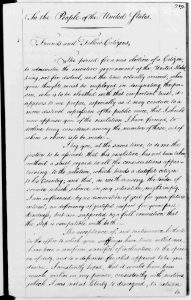

Washington marked up Madison’s 1792 draft and forwarded it to Hamilton. The president’s notes involved some score settling and spleen venting over the attacks on his administration. Hamilton took Washington’s notes and rewrote Madison’s draft, but he prepared a second, clean-sheet document that was more statesmanlike, less burdened by the travails of eight years in office, and intended for the ages.[1] Washington, ever with an eye toward posterity, preferred Hamilton’s approach and worked with him on a final farewell address over the spring and summer of 1796. Washington wanted to announce his retirement as soon as possible to clear the field for other candidates. Hamilton convinced him to put the announcement off, but without much warning, on September 19, 1796 Claypoole’s American Daily Advertiser in Philadelphia appeared with an article on page two addressed “To the PEOPLE of the United States.” Washington, already rumored to be contemplating retirement, had still surprised both supporters and opponents with the release of his Farewell Address, even as he left Philadelphia bound for Mt. Vernon.[2]

Coming at the end of Washington’s public service, the Farewell Address served as a statement of Washington’s theory of republican government, which was by no means assured in the nation’s future. Europe was already convulsed by the wars of the French Revolution, which itself had contributed mightily to the growing split within his own administration. The Republican faction, led by Jefferson, embraced the French Revolution as patterned on the American Revolution and favored a close alliance with France, which was at war with England (among others). Federalists, on the other hand, retained their kinship to England, recognizing it as a better trading partner with significant interests in the Western Hemisphere. They also favored a stronger central government capable of knitting the country together out of an amalgam of states and emerging economic interests.

The internal split colored Washington’s address. He pleaded for unity of government, seeing it as “a main Pillar in the Edifice of your real independence, the support of your tranquility at home; your peace abroad; of your safety; of your prosperity; of that very Liberty which you so highly prize.”[3] In truth, Washington’s plea was not limited to unity of government, but he sought unity in a nation, which meant identifying as an American: “The name AMERICAN, which belongs to you, in your national capacity, must always exalt the just pride of Patriotism, more than any appellation derived from local discriminations.”[4] He was well aware that America in 1796 was more collection of states and regions than a country. But, governed by self-interest, he argued that cooperation among regions with unique characteristics would benefit everyone.[5] According to Washington,

While then every part of our country thus feels an immediate and particular Interest in Union, all the parts combined cannot fail to find in the united mass of means and efforts greater strengths, greater resource, proportionably greater security from external danger, and less frequent interruption of their Peace by foreign Nations; and, what is of inestimable value! they must derive from Union an exemption from those broils and Wars between themselves, which so frequently afflict neighbouring countries, not tied together by the same government’ which their own rivalships alone would be sufficient to produce, but which opposite foreign alliances, attachments and intrieugues would stimulate and imbitter.[6]

Thus, Washington’s appeal to national unity had both cultural and interest-based aspects.

If unity was the aspiration, Washington saw a myriad of threats to it. First and foremost among these, he was concerned with party or the spirit of party. Disagreements over the meaning of the French Revolution and American obligations to its wartime ally rent his administration deeply, as they did over the federal government’s authority, economic policy, and western policy. In 1792, he felt compelled to write to his Secretary of State, Thomas Jefferson—increasingly recognized as a leader of the pro-French faction—and beg him for greater charity when dealing with cabinet members who held different opinions, arguing, “how much is it to be regretted then, that whilst we are encompassed on all sides with avowed enemies & insidious friends, that internal dissentions should be harrowing & tearing our vitals. The last, to me, is the most serious—the most alarming—and the most afflicting of the two.”[7] Within days, he sent a similar letter to Alexander Hamilton, Jefferson’s chief antagonist. Unfortunately, the pleas fell on deaf ears.

The split over foreign policy grew particularly divisive. Washington increasingly sided with the Federalists, particularly in his policy of studied neutrality in the wars plaguing Europe. Washington sent Chief Justice John Jay to negotiate a new treaty with England clarifying their relationship after the Revolution. Tensions exploded on the streets after the Jay Treaty became public. Federalists viewed it as necessary for American security, but Republicans considered it a betrayal of the principles of liberty, which the French initially claimed to champion, and friendship, which they felt Americans owed France for its contributions to the American Revolution. For their part, Republican attacks grew increasingly strident and personal, the charge being led by The Philadelphia Aurora and its publisher, Benjamin Franklin Bache, Benjamin Franklin’s grandson. During public discussions, Jay was burned in effigy so widely that he joked he could walk from Georgia to Massachusetts by their light.[8] While Washington was willing to suffer the barbs and arrows of a hostile press for his decisions—he had a clear conscience in his motivations—he was concerned that they would “destroy the confidence which it is necessary for the People to place (until they have unequivocal proof of demerit) in their public Servants.”[9]

Complicating things further, protests in western Pennsylvania over the whiskey tax began in Washington’s first term, but grew violent as Washington began his second term. Mobs in Pennsylvania had tarred and feathered federal tax collectors over the whiskey tax, eventually leading Washington to raise an army for the suppression of rebellion in western Pennsylvania. Further violence was easy to envision.

In that context, Washington’s drift closer to Federal positions, his plea for unity, and his condemnation of party can be easily read as a thinly veiled attack on the Republicans, who had been his worst critics. From anyone else, the words would sound perilously close to the sentiments of a dictator who questioned all opposition or disagreement with his decisions and identified his own wishes as synonymous with those of the popular will. Republican concerns about the ease with which Washington might become a king are easy to understand. Indeed, they were very critical of the address.[10] However, coming with the simultaneous announcement of his retirement from public life and voluntary surrender of power—which Washington had done once at the end of the Revolution after facing mutinous officers—could only force future generations to wrestle with his arguments.

Rather than score settling, Washington’s farewell represents his decision to more publicly voice his thoughts about the American form of representative government. Because he saw popularly elected constitutional government as the ultimate expression of the popular will, opposition to that government’s actions constituted a particular danger to it. According to Washington:

All obstructions to the execution of the Laws, all combinations and Associations, under whatever plausible character, with the real design to direct, control counteract, or awe the regulation deliberation and action of the Constituted authorities are distructive of this fundamental principle and of fatal tendency. They serve to organize faction, to give it an artificial and extraordinary force; to put in the place of the delegated will of the Nation, the will of a party; often a small but artful and enterprising minority of the Community; and, according to the alternate triumphs of different parties, to make the public administration of the Mirror of the ill concerted and incongruous projects of faction, rather than the organ of consistent and wholesome plans digested by common councils and modified by mutual interests.[11]

Today, Washington’s plea to avoid parties and factionalism may sound naïve. But, of course he was not new to high-risk politics, political violence and the baser motivations and actions that could affect people. Washington was well aware of what it had taken to achieve independence and build the new country, probably more so than any man alive.

Washington acknowledged that the “spirit of party” was “inseperable from our nature” and had often been controlled, stifled, or repressed in undemocratic societies. But, he also held that it was a most pernicious threat to republican government. Washington expected political parties to alternately succeed and fail in a contest for control of government through manipulation of popular passions and misrepresentation of their own goals and motives, as well as those of their opponents. Victory in these contests would result in acts of revenge against the losers. Eventually, one party would succeed in institutionalizing its success, denying access to the levers of power to any who failed to subscribe to its principles. In short, it would result in a kind of political despotism, in which the interests of the whole nation took a back seat to the interests of the victorious party. Thus, even while acknowledging this outcome was an extreme case, Washington felt it necessary to warn his countrymen about an inherent problem he perceived in popular government.[12] It all began with the kind of factionalism he had experienced as president.

Being a practical man, Washington also left his countrymen with practical advice: minimize debt, avoid a standing army to minimize expenditures, maintain neutrality among nations so as not to go to war either on the behalf of allies or out of emotional animosity towards enemies, ramp up defenses quickly in an emergency to deter aggression, promote the diffusion of knowledge to better inform the public’s opinions, recognize that religion and morality are indispensable to political prosperity, and exercise caution in adjusting the Constitution and wielding power under it. Over time, these became maxims. From the Civil War through the 1980s, the address was read routinely in the House of Representatives and the Senate on Washington’s birthday.[13]

Washington’s Farewell Address is a product of its times, as all presidential farewells must be. But, with a prod from Hamilton, Washington recognized the opportunity to communicate a message larger than a simple announcement of his retirement and response to his critics. Instead, he offered thoughts for citizens of the young republic to consider as they embarked on the grand experiment of representative government. Forty-five presidents and two and a half centuries later, as the country recently transitioned from one president to another, they are still worth considering.

[1] Ron Chernow, Washington: A Life (New York: The Penguin Press, 2010), 753; David S. Heidler and Jeanne T. Heidler, Washington’s Circle: The Creation of the President (New York: Random House, 2015), 385-387.

[2] Heidler and Heidler, Washington’s Circle, 393.

[3] George Washington, “Farewell Address,” Selected Writings (New York: Library of America, 2011), 367. Washington was an eighteenth century writer, fond of run-on sentences and spellings peculiar to modern ears. They have been retained from the original.

[4] Washington, “Farewell Address,” 367.

[5] Washington, “Farewell Address,” 368.

[6] Washington, “Farewell Address,” 368.

[7] George Washington to Thomas Jefferson, August 23, 1792, in Selected Writings, 321.

[8] Thomas Fleming, The Great Divide: The Conflict between Washington and Jefferson That Defined America, Then and Now (Boston: Da Capo Press, 2015), 209-210.

[9] George Washington to Henry Lee, July 21, 1793, in Selected Writings, 332.

[10] Richard Norton Smith, Patriarch: George Washington and the New American Nation (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1993), 283-284.

[11] Washington, “Farewell Address,” 370-371.

[12] Washington, “Farewell Address,” 372.

[13] U.S. Senate Historian’s Office, http://www.senate.gov/artandhistory/history/common/generic/WashingtonFarewell.htm, accessed December 16, 2017; Historical Highlights, U.S. House of Representatives, http://history.house.gov/HistoricalHighlight/Detail/36742, accessed December 16, 2017. The practice in the House fell off during the 1970s and 1980s. It is still honored in the U.S. Senate.

Recent Articles

When Some Americans First Lost Their Constitution

The Great Contradiction: The Tragic Side of the American Founding

Reluctant Ally: The Dutch Republic and the American Revolution

Recent Comments

"The Complicated History of..."

Carole, Thank you, I appreciate that. I agree that much of what...

"The Sieges of Fort..."

I very much enjoyed your well-written article. Interest in the site continues,...

"An Enemy at the..."

Bob: Great Article! I never heard of Abraham Carlile and his fate....