“The lives of malefactors in general are prefaced with a strong outline of their birth, parentage and education, with other peculiar circumstances belonging to them. As for instance, A.B. was born in the parish of ―――――, in the county of ―――――, of reputable and genteel parents, but falling early in life into bad company both of wicked men and lewd women, he contracted habits which ultimately led to the gallows.” So begins George Hanger’s picaresque account of his life, adventures in the American Revolution, and opinions, which, while extremely free with the last, is remarkably short with the rest.[1]

THE FORMATIVE YEARS

George was born on October 13, 1751 at Driffield Hall, a country seat of his father Gabriel in the hamlet of Driffield near Cirencester. The youngest of three surviving sons, he has little to say about his birth: “I was born … in the best bed in the state room, according to ancient custom. Whether I came headforemost or not into the world or whether I was born with teeth in my gums or with hair on my head it will not be expected that I should determine, having no other record to go by than a treacherous memory, but I am inclined to believe, if I may judge from the length of my nose, that at my birth the midwife committed some indignity to my person.” Otherwise all he has left is the following quatrain:

Three pretty boys did Gabriel get,

The youngest George by name, Sir,

A funny dog, not favoured much

By fortune or by fame, Sir.

Gabriel was the son of Sir George Hanger Bt., a turkey merchant, and had gone out to Bengal with £500 in 1714, making his fortune as a merchant with the East India Company. When he returned to England in 1725, he had accumulated £25,000[2] and soon after became the sole legatee of his four brothers and two sisters, all of whom died without issue. An exceedingly wealthy man, he went on to become a Whig MP and was elevated to the peerage in 1762, becoming Lord Coleraine. He was, according to George, “one of those respectable, independent, old English characters in the House of Commons called country gentlemen, who formerly had a considerable influence with the Ministers and to whose judgements and opinions every Minister paid the greatest respect … I am confident he never received a bribe [and] I believe from my heart he was as honest a man as ever stepped in leathern shoe.” He died in 1773, aged seventy-six.

George’s mother Elizabeth was the daughter of Richard Bond of Cobrey Court, Herefordshire, and married Gabriel in 1736. “In my mother,” confides George, “I have experienced a most affectionate, kind and tender parent.” Aged sixty-five, she died in 1780.

George began his formal education at Reading School, an academy for boys founded in 1125 and still in existence. In his day the school was located in the former Hospitium of St John, the main building of which remains, but the refectory, which housed the schoolroom, was demolished in 1785 and is now the site of Reading Town Hall.

A very idle boy, George could never be induced to look into a book until it was forced under the shadow of his nose in the schoolroom. As a result he used to be beaten with such cruelty that on the representation of his brothers he was removed and sent to the Reverend Mr. Fountain’s at Marylebone, London. Located in the Manor House, which was demolished in 1791, the school was, so George says, the best for little boys that ever was. “They were treated with the utmost kindness and attention, and with proper correction, but only when it appeared to be absolutely necessary … Whatever I learned was from kind and gentle treatment, for beating would not go down with me. A kind word and my lesson explained to me had more effect than all the sticks and rods in Christendom, for I was bold and daring even at that early age.”

From Marylebone George went on to Eton College in 1764. Located in the small town of Eton on the opposite bank of the Thames to Windsor, it had been founded by Henry VI in 1440 and was by now the leading English boarding-school. Offering a rigorously classical syllabus, it provided advantages that were more social than educational.

While at the start of each term most boys came down by coach from the Swan with Two Necks tavern in London, George had only six miles to travel from his father’s other country seat, Cannon Place, in the hamlet of Bray north-west of Eton. Unlike the King’s Scholars, that is to say, some 70 poorer scholarship boys whose places were provided under the medieval statutes of the college, George belonged to the Oppidans, some 430 fee-paying boys who were the sons of the aristocracy, the church, the landed gentry, and other members of the Establishment. Whereas the King’s Scholars slept in one huge dormitory, the Long Chamber, and were fed and clothed by the college, George as an Oppidan would live in a private boarding-house and be able to supplement his fare and provide for his clothing by purchases from the shopkeepers and publicans in the High Street.

On arriving at his boarding house George would have been sent to the college to collect sheets and bedding. Otherwise such abodes were run almost independently, though the college was of course responsible for schooling. Bedchambers commonly housed two to four boys. Next day George would have called at the college to be assigned a tutor, whose fees, like those of the headmaster, were not paid directly but formed part of the end-of-term accounts of the boarding house presented to his father. Purchases of provisions and liquor ― not to mention clothing, which became a foppish and profligate interest of George ― were included either in the account or in separate ones presented by shopkeepers and publicans in like manner. So began George’s ruinous habit of shopping on credit, a practice that would land him in hot water later in life.

On arriving at his boarding house George would have been sent to the college to collect sheets and bedding. Otherwise such abodes were run almost independently, though the college was of course responsible for schooling. Bedchambers commonly housed two to four boys. Next day George would have called at the college to be assigned a tutor, whose fees, like those of the headmaster, were not paid directly but formed part of the end-of-term accounts of the boarding house presented to his father. Purchases of provisions and liquor ― not to mention clothing, which became a foppish and profligate interest of George ― were included either in the account or in separate ones presented by shopkeepers and publicans in like manner. So began George’s ruinous habit of shopping on credit, a practice that would land him in hot water later in life.

As George summarised his schooling, “I really made considerable progress in my learning and by the time I got into the fifth form I was a very tolerable Latin scholar and could construe most books with sufficient readiness. But I took a most decided aversion to the Greek language and never would learn it.” Such a summary naturally falls far short of telling all. For instance, Eton began in George’s day to encourage the performance and imitation of classical texts, including comic writing in ancient styles, so that the years spent by George in construing, writing and performing nurtured the wit for which he later became famous.

Outside school a high old time was had on free days with recreational pursuits ranging from dashing about town in small racing carriages, swimming in the Thames, and racing skiffs along it, to brawling with bargemen and local youths, attending cockfights or bull- or badger-baiting, and hunting water fowl. Boys also participated in cricket, “Eton Fives”, and other obscure games too numerous to name. For those interested in real-tennis a court was available, and for those who were perhaps less active billiards could be played in Windsor. Betting ― for example on horses, prizefighters, dogs, badgers, and games ― was rife. A favourite winter pastime was rat-catching in infested older buildings. In later life George would publish “the rat-catching secret” and ever after be accorded the sobriquet “the rat-catcher.”

Schooling eventually took a back seat in George’s life. “My studies after some time had a different direction, for, from the moment I came into the fifth form, I studied everything but my book. My hours out of school in the day were employed in the sports of the field, being already fond of my dog and gun. By night game of another kind engrossed my whole attention. At that early period I had a most decided preference for female society and passed as much time in the company of women as I have ever done since. A carpenter’s wife was the first object of my early affections nor can I well express the nature of my obligations to her. Frequently have I risked breaking my neck in getting over the roof of my boarding house at night to pass a few hours with some favourite grizette of Windsor. During the latter part of my time at Eton, to perfect my education, I became attached to and was much enamoured of the daughter of a vendor of cabbages.”

Nor did George’s early acquaintance with female society end there. “The big boys had a very wicked custom every Sunday of resorting to Castle prayers at Windsor, not to seek the Lord, but to seek the enamoratas who constantly and diligently attended to receive our devotions. Besides, in summer time it was our custom to walk in the public promenade in the [Windsor] Little Park. My father lived only six miles from Windsor and consequently I was as well known to every family in that town and neighbourhood as the King himself; but notwithstanding this, I constantly walked with some fair frail one arm in arm with as much sang-froid as I now would walk in Kensington Gardens with a beautiful woman.”

When George left Eton in the summer of 1769, he did not go to either Oxford or Cambridge, as was customary with most young men of his ilk. “This was,” he intimates, “a very fortunate circumstance in which my father shewed his superior judgment. As I had resolved on being a soldier, a German education was best suited to the profession I had chosen. Had I been placed at Oxford or Cambridge, not being of a studious disposition, my health might have suffered from every species of riot and dissipation, which is so prevalent at our universities, and my mind would have remained in the same uncultivated state at my departure as at my arrival, for it is a hundred to one if I had ever read any literary works except the Sporting Calendar and the newspaper. I was accordingly sent into Germany, to Göttingen, which is one of the most celebrated universities in the world.”

George spent about twelve months at Göttingen, applying himself to mathematics, fortification, and the German language. In the town he found generally too many English, “who herd together and by always talking their own tongue never acquire a fluency in that of the country, which can only be obtained by associating with the natives.” For its part the university was not entirely to his taste. Containing a reclusive set of learned professors whose knowledge extended no farther than the lectures they delivered to their students, it was no place for acquiring those elegant and polite manners so essential to an officer. Moreover, the society of women of the first manners, fashion and education, “without which no mind can be polished,” was wanting. So he moved on to the Courts of Hanover and Hesse-Cassel.

At Hanover George was patronised, “in every sense most flattering to my feelings,” by Prinz Karl von Mecklenburg-Strelitz, a brother-in-law of George III, and was befriended by various officers, including Generals Freytag and Luckner, veterans of the Seven Years’ War. While there he was introduced to the nobility, passed his time constantly in polite circles, and was instructed in the discipline of light cavalry. He attended all the Hanoverian reviews and even a Prussian one lasting four days near the town of Magdeburg.

From Hanover George carried letters of recommendation to the Court of Hesse-Cassel. The Hauptstadt, Cassel, was, he says, one of the cleanest and most delightful towns that he had ever beheld. “The new town is built entirely of stone and, on approaching it from a distance, has a very beautiful and grand appearance.” Little did he imagine, when introduced at Court, that one day he would come to serve in the Landgrave’s army.

“No part of my life,” George confides, “has been so pleasant and agreeable as the three years[3] I passed in Germany. I cannot help remarking with what elegance a person of small fortune may live in that country. In England, with a small income, one can scarcely procure necessaries of life. My father allowed me three hundred pounds per annum[4], which was fully sufficient for all my expences, and at the end of the year I had always an agreeable overplus.”

The hospitality and the open, honest character of the Germans so attached George to the country that when he was ordered home to join his regiment, he quit it with much reluctance and absolutely shed tears on his departure. He had been commissioned an ensign in the First Regiment of Foot Guards on January 31, 1771, a rank which carried with it a captaincy in the rest of the army.

As George set out for home, little did he know that events would soon take a marked turn affecting the entire course of his life.

THE SPORTING ROVER

On his return to London in autumn 1771 George immediately joined his regiment and took up residence in St. James’s not far from his father’s place in Pall Mall.

St. James’s was the most fashionable parish in London. It contained a great number of elegant houses belonging to persons of distinction and at its centre was St. James’s Square, pretty large and well paved, with a noble basin in the centre surrounded by a palisade. Bordering it on each side were fine houses inhabited mostly by the aristocracy. To the south lay St. James’s Palace, built by Henry VIII, and beyond it St. James’s Park, near a mile and a half in circumference. On all sides of the park were beautiful walks and in the centre, extending almost the whole length from east to west, was an imposing canal, at the east end of which was Horse Guards’ Parade, where George and his regiment would muster and perform their exercises.

Of the time when he began his round of training, parades, and guard duty at the Royal Palaces, Tower of London and Windsor Castle George was later to observe, “I may with truth say that I knew my duty better than nine ensigns in ten at their debut on the [Horse Guards’] parade at Whitehall, for I not only was acquainted with the common parade duty but absolutely knew the manœuvre of a battalion, for I had made my profession my study and was devoutly attached to a military life.”

George arrived in town as St. James’s was being transformed. Quiet streets were becoming crowded with servants and tradesmen as they prepared to receive the nobility with their extended families and entourages, who would soon arrive from the country for “the season” ― the period from November to June when Parliament most often sat. Together, the peers and their immediate relations comprised preponderantly London’s high society ― known in its day as the beau monde, an elite consisting of no more than a few hundred individuals of which George was a member. Marked by ostentatious consumption and fast living, it was an exclusive world which set the “tone” in fashion. Yet membership did not depend on being modish or trendy alone, but rather on pedigree, connections, manners, language, appearance and much else besides.

Despite its glittering public facade, the core business of the beau monde was in fact politics. Peers had a hereditary right to sit in the House of Lords and dominated the Cabinet. For its part the House of Commons was packed with members who boasted direct blood lines to the peerage, whereas ownership by peers of extensive acreage and property endowed them with sizable and direct control over numerous parliamentary seats. It is against this background that high society provided a forum in which parliamentary business could be discussed and political information exchanged.

It was not, however, politics which interested George so much as the pursuit and company of titled women, many of whom were irresistibly attracted by his combination of wit, immense charm, craggy features, fine physique, and larger-than-life personality. Whether it was daytime visits to private residences, balls, masquerades, salons, dinners or suppers, private social or gaming parties, outings to the theatre or opera, excursions to the pleasure gardens of Ranelagh or Vauxhall, and so on, the beau monde offered a mosaic of opportunities for social encounters.

It was not long before George’s rake’s progress through high society came to the attention of the press. According to one report, it is not believed “our hero is much disposed to attach himself for any length of time to a single mistress. Universal benevolence to the Ladies is his motto and he has fully approved himself worthy of the device.” While he had always distinguished himself as a brave and judicious officer, “his amorous campaigns have been still more numerous and successful, and though he is too prudent a commander to glory in these conquests, some of them have been so manifest to the world that he could not conceal his victories. Valour and gallantry go hand in hand and the reason is in a great degree obvious: the ladies will not risque their reputation with a poltroon, who is too apt to boast of favours which he has never received and can neither defend himself or a lady’s character if attacked, whereas the man of honour, who must be a man of spirit, carefully conceals his happiness and is ready to vindicate the character of his mistress at the price of his life. To this disposition we may chiefly ascribe the high reputation that Captain Hanger holds among the ladies, for … no woman of taste disdains to rank him amongst the number of her admirers.”

To the accuracy of the report we may attest George’s own words: “I have held it as sacred as my creed that it was an excess of infamy either to betray or expose favours granted or confidence reposed, … for, so help me God, I have never yet betrayed a woman nor ever intentionally injured one of the sex nor ever exposed their weakness or hurt their feelings.” Yet despite George’s discretion the names of several of his lovers did become public knowledge, as the press revealed.

There was, for example, Lady Sarah Bunbury, a daughter of the second Duke of Richmond and Lennox. Born in 1745, she was at one time widely spoken of as a possible match for the future George III, but it was as chief bridesmaid rather than bride that she eventually attended the royal wedding. In 1762 she broke a secret engagement to Lord Newbattle (later the fifth Marquess of Lothian) to marry Sir Charles Bunbury Bt., a Whig MP for Suffolk, but the marriage was not a success. Cold and reserved, Sir Charles was reputedly more attentive to his first love of horses than to his wife. Some five years later she became pregnant by her cousin Lord William Gordon, a son of the third Duke, and left the marital home never to return. Fleeing to Scotland, they co-habited for a short while, but by 1770 the affair was over. One of the foremost beauties of her day, she led the hyper-critical Horace Walpole to exclaim, “No Magdalene by Correggio was half so lovely or expressive!”

Then there were Harriet Lamb and Helen Kennedy. Harriet was a daughter of Sir Matthew Lamb Bt. and a sister of Peniston Lamb, Lord Melbourne, whereas Helen was a second cousin of David Kennedy, the tenth Earl of Cassillis. And so George’s progress continued, so that to his list of lovers, if the press is to be believed, “may be added almost all the first-rate women of spirit.”

Nor were George’s amorous adventures confined to St. James’s alone. As the season ended and spring turned to summer, members of the beau monde would return to the country, attend leisure towns such as Bath, Brighton and Scarborough, or take the waters at resorts abroad. One such resort visited by George and frequented by European nobility was Spa in the Prince-Bishopric of Liège, a territory which bisected the Austrian Netherlands. Lying in a wooded valley surrounded by undulating hills and countless rivers and springs, it was, besides the waters, noted for its casinos, one of which, the Casino de Spa, is the oldest in the world.

That George had been up to his old tricks was as usual related by the press: “When the Captain was at Spa, he there met the amiable Mrs. Pitt, mother to Lady Ligonier. She was then still in her prime after having been a reigning toast for a succession of years. Her natural dispositions prevailed in favour of Mr. Hanger, and as they lodged in the same house, they had frequent opportunities of testifying their mutual approbation. This lady has since retired to the south of France.”

Penelope Pitt, a daughter of Sir Henry Atkins Bt., was in her early 50s, having married in 1746 George Pitt, the Tory MP for Dorset. In 1776 she would become Lady Rivers when her husband was elevated to the peerage. Theirs was not a happy marriage and in 1771 they separated. She went on to live mostly in France and Italy till her death in 1795, when she was buried in the Old English Cemetery at Livorno.

Almost inevitably George’s conduct gave rise to scurrilous and unfounded rumours about him. He was, for example, accused of having an affair with the Hon. Henrietta Wymondesold, a daughter of Lord Luxborough, which led to the breakup of her marriage with Charles, a member of the landed gentry from Wanstead in Essex. Yet the breakup occurred in 1751, the year of George’s birth, and she died in 1763!

Despite his many relationships with ladies of distinction, George proceeded to cast his net wider, beginning with the demi-reps of the theatre. The demi-rep, or fashionable courtesan, was a woman whose sexual reputation had been compromised but who was able to maintain a position of sorts in fashionable circles due most often to the financial support of her lover. Into this class fell various actresses of the day. George’s first liaison was with Mrs. Maria Bailey, an actress at the Haymarket, who had recently been the mistress of Prince Henry Frederick, the Duke of Cumberland and Strathearn, a nephew of George III. Before long he was also involved with Mrs. Jane Lessingham, an actress at Covent Garden born in 1739. Again, the press did not fail to comment: “At the time Mrs. Lessingham, an actress, was supported in a most splendid manner by Admiral Barrington. Whilst he was gaining laurels for himself and glory for his country abroad, the Captain most politely attended her at home to prevent her grief becoming too violent in the absence of her naval admirer.” Insatiable, George moved on, as the press duly reported: “The amiable Mrs. Saunders,” another actress at the Haymarket, “whose character was for a long time equivocal and who in public never exceeded the bounds of a demi-rep, seemed to have a peculiar predilection in favour of Captain Hanger. He was constantly in all her parties and their frequent tête-à-tête excursions made it suspected that even a woman of fortune might have strong partialities for a favourite admirer.”

Of all the actresses with whom George dallied the most enchanting to him was Mrs. Sophia Baddeley, a woman of exceptional beauty with a vivacious personality. A leading actress and singer at Covent Garden and Drury Lane, she was not averse to selling her sexual favours to a succession of admirers, among whom ranked the Duke of York, the Hon. William Hanger (George’s eldest brother), the Lords Grosvenor and Melbourne, Sir Cecil Bishop, Hananel Mendes da Costa, a wealthy merchant trading in copra with India, and George Garrick, the theatre manager.

During the 1771-72 season Sophia quit the stage. “During this recess,” revealed the press, “Captain Hanger was introduced to her and so fervently pleaded the cause of love that our heroine yielded to his intreaties. The Captain still entertains a very great regard for her, accompanies her to all public places, and protects her with a spirit that does him honour. An instance of his behaviour will illustrate our observation. At the opening [in January 1772] of the Pantheon,” a subscription venue offering fashionable entertainment such as balls, concerts and masquerades, “the proprietors endeavoured to exclude all women whose characters were suspicious, many of them having made their appearance on the first night, which greatly hurt the delicacy of some squeamish women of quality, whose reputations were as equivocal as those of the females they were desirous of expelling. Captain Hanger accompanied Mrs. Baddeley on the second night, when the doorkeeper refused her admittance, saying he was authorised to reject what company he thought improper. Captain Hanger insisted upon knowing his authority, to which the doorkeeper replied he had the proprietors’ orders for what he did. Captain Hanger then ordered the doorkeeper to bring the proprietors to him who had given these commands. The servant excused himself by saying they were not present. Captain Hanger then bid him produce the master of the ceremonies as he was the ostensible manager. Captain Donnellan did not chuse to appear upon the occasion but gave orders for Mrs. Baddeley’s admission ― and this resolute behaviour of Captain Hanger obliged the proprietors to lay aside all thoughts of requiring every female who desired admittance to the Pantheon to bring a certificate of her virtue in hand.”

For a while George’s progress came to an abrupt stand when he fell deeply in love with a Romany girl at Norwood, a village a few miles south of London on a high road to the coast. They were married according to Romany rites but soon afterwards she ran off with a travelling tinker of a neighboring tribe. In despair George reacted by descending into the depths of drunkenness, riot and dissipation.

A man of prolific sexual appetite, whose long nose seemed to confirm the old adage that men with great noses make great lovers, George began to cast his net even wider, resorting to prostitutes of every class. In his day London had more prostitutes plying their trade, whether on the open streets or not, than could be found anywhere else in Europe. The city was indeed the sex capital of Europe and perhaps of the world. There were the poor streetwalkers who slept rough and haunted the streets at all times of the day and night, many of whom were infected with venereal disease; the women who operated from rented rooms and solicited in the streets and taverns; the higher-class prostitutes who frequented fashionable bagnios, seraglios, “nunneries” or brothels under the protection of madams; and finally the demi-reps or high courtesans who were most often the kept mistresses of rich, influential or powerful men. None escaped George’s attention.

Looking back, George was to admit, “I was early introduced into life and often kept both good and bad company, associated with men both good and bad, and with lewd women, and women not lewd, wicked and not wicked ― in short, with men and women of every description and of every rank from the highest to the lowest, from St. James’s to St Giles’s[5], in palaces and night cellars, from the drawing room to the dust cart. The difficulties and misfortunes I have experienced, I am inclined to think, have proceeded from none of the above mentioned causes but from happening to come into life at a period of the greatest extravagance and profusion. Human nature is in general frail, and mine I confess has been wonderfully so. I could not stand the temptations of that age of extravagance, elegance and pleasure. Indeed, I am not the only sufferer, for most of my contemporaries and many of ten times my opulence have been ruined.”

George “has made himself so very conspicuous upon the theatre of gallantry and dissipation,” began an interesting article in July 1777, “that all our town readers will immediately know him, and it may seem extraordinary that he has so long escaped our observation. The truth is we have been lying in wait for him some time, but the eccentricity of his conduct and the variety of his amours prevented our tracing any particular attachment till the present; and as it may be of short duration, we have seized this opportunity of delineating his character and laying before our readers his extraordinary exploits.

“When at school,” the article continued, “we find him much more addicted to plundering orchards than inclined to his studies. Indeed, he had an utter aversion to Greek and took more delight in the company of the pretty females in the neighbourhood than with either Homer or Virgil. He signalised himself very early in the service of the fair sex, and ere he was seventeen he had a child sworn to him by a maid servant and was flogged in school after being at least a nominal father for his As in præsenti.[6]”

On repairing to the metropolis George “soon signalised himself in all public places as a buck of the first head. Having obtained a commission in the army, the Captain was well known about the gardens at Vauxhall and Marylebone [frequented by prostitutes] and the ladies of easy virtue found him a very good friend as his purse was constantly dilated to their wants and wishes. Such a career brought him to distress and he was obliged to have recourse to usurious Israelites to raise the necessary supplies as his guardian positively refused paying a number of superfluous debts which he had created. His pocket alone did not suffer by these debaucheries, but his health was much impaired and he found it necessary to make a temporary retreat.”

On proposing to his guardian a tour upon the Continent George was advised, if he went to see the world, to take particular care the world should not see him. “The Captain either did not or would not understand Old Square-toes but set off for Paris to make a figure[7] in that capital. He had not been long there before he became the subject of public conversation, being constantly seen in the Tuileries, the Palais Royal, the guinguettes,[8] and the rest of the public places, flushed with burgundy and champagne. He had, however, the luck to escape any rencontres[9], as, to do the French justice, they make great allowances for the behaviour of Englishmen, which they would not do in favour of their own countrymen.”

George became enamored of a poor figurante[10] who had been hackneyed in the sérails[11] and upon the pavements of Paris. “It is true,” observed the article, “he found her an easy conquest as she found him an easy dupe, and he enabled her to assist a corporal of dragoons who was her cher ami to the summit of his wishes. In a word, as poor a figurante as she was upon the stage, he was in her opinion a poorer figurant upon the theatre of love, where he seldom appeared but when intoxicated.

“Having exhausted his letter of credit, it was time for him to think of returning home, which he did with regret at leaving his fond and faithful mistress. Upon his appearance in England, much improved, no doubt, by his travels, he renewed his former acquaintance and, being now in full possession of his fortune, gave an ample scope to his disposition and genius.

“He shone with uncommon éclat at all the masquerades,” the article went on, “where he was generally noisy and riotous from inebriation, whereby he obtained the title of Captain Toper. His exploits in King’s Place[12] are registered in Charlotte Hayes’s annals of dissipation and riot, and her bills for broken looking glasses, china and the like amounted in one week to a very considerable sum. The Captain’s dexterity in this kind of destruction was not confined to this lady’s house only. Every nunnery in that neighbourhood as well as the New Buildings can evince his extraordinary feats. His prowess he also testified in many other ways, and tho’, unlike Don Quixote, he never tilted with a windmill, he has often attacked, sword in hand, those innocent and useful vehicles called sedan chairs; and to his skill and courage, be it spoken, he has often vanquished a whole phalanx united. Their wounds, though not mortal, have often created a great mortification in their masters when they discovered the fatal effects of the preceding night.

“In his intrigues he has oftentimes been unlucky. His ambition has ever excited him to have amours with women of some consequence in a certain line, but his constant state of intoxication, added to his natural disposition for riot and confusion, has frequently precluded him from the arms of those desirable females whom he has so ardently wished for. The waiters at Lovejoy’s and the other houses of modest recreation knew it was in vain to send for these ladies in his name as they would never come.”

By some accident George became acquainted with Mary Frederick, wife of John (1750-1825), the MP for Newport, Cornwall, who would succeed to a baronetcy in 1783. “This lady,” the article reported, “agreed to keep him company on condition that he would never call upon her but when he was in a perfect state of sobriety. To these terms the Captain agreed and for a few days fulfilled the contract. But one morning returning from Vauxhall overcharged with claret, he called upon her before the servants were stirring, and not obtaining immediate entrance, he broke all the windows and raised so great an uproar that the watchmen took him to the round house, where he was confined till he recovered his senses. This outrage broke off the connection as Mrs. Frederick would not keep up a correspondence with a man of such a violent disposition.”

George then crossed the path of Lady Grosvenor, wife of Richard, the first Baron, who in 1769 had caught her in flagrante delicto with Prince Henry Frederick, the Duke of Cumberland and Strathearn. They separated. According to the article, “The Captain made an attempt one night upon Lady Grosvenor at the Pantheon, and as he was masked and tolerably sober the beginning of the evening, he probably might have prevailed as he was one of the best dressed masks in the place and had a very handsome diamond ring upon his finger which greatly attracted her ladyship’s attention; but before morning he applied so often to the bottle to drink libations to his angelic mistress that he lost her for want of recollecting her dress. The Captain met her ladyship the next masquerade night at Conelys’[13] when he renewed his addresses, but she treated him with the greatest coolness, considering his former behaviour as an intended affront. He now had recourse to the bottle to dissipate his melancholy for the loss of his angelic mistress and once more got most compleatly intoxicated upon her ladyship’s account.

“This was,” the article concludes, “the state of Captain Toper’s amours when he made an acquaintance with ‘the Hibernian Thais’[14],” the daughter of a tradesman in Dublin who had run away rather than marry. “Her temporary wants induced her to yield to the Captain; a pressing mercer may be said to have been his Mercury upon this occasion. The Captain’s purse quieted the urgent trader and promoted his suit. It is somewhat singular that the Captain since this connection has only broken two of her pier-glasses and one set of china. He has, however, replaced them and promises never to be guilty of a like offence. How long he will keep his promise cannot be ascertained, but this is certain, if the Captain breaks a favourite set of china which she doats upon, she will certainly break with him.”

“I must,” claims George, “have been more than a man, or, more properly speaking, less than a man, not to have indulged in the pleasures of the gay world, which I could not partake of without being at a very considerable expence, by far more than my income could afford.” His estate in Berkshire, bequeathed to him by his aunt, Lady Coleraine of the first creation, brought in a rent of £200[15] a year; otherwise all he possessed was £3,000 in cash as a youngest son’s fortune. Yet his outlay on clothes alone was immense. “I was,” he admits, “extremely extravagant in my dress. For one winter’s dress-clothes only, it cost me nine hundred pounds. I employed other tailors to furnish servants’ clothes and morning and hunting frocks etc. for myself.” In particular he always made a point of being handsomely dressed at each celebration of the King’s birthday, but for one especially, he put himself to very great expense, having two suits for the day. “My morning vestments cost me near eighty pounds and those for the ball above one hundred and eighty. It was a satin coat brodé en plain et sur les coutures and the first satin coat that had ever made its appearance in this country. Shortly after, satin-dress clothes became common amongst well dressed men.”

“I never was fond of cards or dice,” asserts George, “nor ever played for any considerable sum of money ― at least no further than the fashion of the times compelled me. I claim, however, no merit whatever for abstaining from play, as it afforded me no pleasure. If it had, I certainly should have gratified that passion as I have done some others.” Nevertheless, cards did feature in a press report about him that appeared in May 1772. “The Captain is lately returned from a tour in Ireland, where the Hibernian beauties paid him a regard not inferior to the English toasts. An anecdote has transpired that does great honour to his humanity and generosity. Whilst he was in the capital of that kingdom, being one evening in Lucas’s coffee house, he met with a young gentleman who lodged in the same house with him and who was in possession of a sum of money given him by his relations as his fortune to purchase a commission, and was accordingly upon the point of embarking for England. A party at piquet was proposed and Captain Hanger was so very successful that he won all the young gentleman’s cash. Upon their return home together Mr. Hanger perceived his late antagonist extremely gloomy, and after he had retired to his own apartment, the Captain had the charitable curiosity to listen to a very extraordinary soliloquy which concluded with, ‘Since all hopes are vanished, this pistol shall do its office.’ The Captain immediately rushed in, prevented the execution of this rash sentence, and insisted upon his coming down into his lodging and drinking a bottle. By plying him plentifully with the crimson juice he diverted his thoughts till morning, when the Captain contrived to remit him his money in notes by letter supposed to be sent by a lady who entertained a very high opinion of his merit. The young gentleman did not discover the kind and genteel imposition till after he had arrived in England. He has since purchased a cornetcy of dragoons and now relates this adventure so greatly to the Captain’s advantage.”

Before the age of twenty George had fought three duels, but whether with the épée or pistol he does not say. “In those days,” he relates, “I was in great habits of fencing, having a person to attend me three times a week to perfect me in that science. Being very strong in the arm and wrist, I was ever prepossessed with an idea that if I could, unobserved, change from the one side of my adversary’s blade to the other and beat on it, I should be certain of hitting the very best fencer. This was a favourite coup of mine.”

It was during his years in London that George began to gain a reputation for eccentricity, centred as much on the singularity of his widely expressed opinions as on his untoward behaviour. He was, for example, a firm advocate of polygamy, not in general, but in severely restricted circumstances. In short, a man should not be entitled to take a second wife “merely from caprice or fancy but only in case of some mental or corporeal defect which renders his cohabiting with his former wife impossible.”

Never one to deny himself the pleasures of the flesh, George was also keenly interested in the sports of the turf and field. “The turf,” he confesses, “I was passionately fond of and indulged that pleasure to a very great extent. I once stood three thousand guineas on one race, Shark against Leviathan, and won it; my confederate, Mr. Robert Pigott, stood five thousand on the event. I was a considerable gainer by the turf notwithstanding the enormous expence of keeping running horses in those days, as every horse in training at Newmarket cost the owner between eighty and ninety pounds a year if not moved from that place, but if he travelled the country, it was computed, to clear himself, he must win three fifty-pound plates during the summer. To use the idea, but not the precise words, of Macheath,[16] I can with truth say the turf has done me justice.” A published subscriber to the Racing Calendar and the Sporting Calendar, George was a member of the Jockey Club and involved in making the matches, sweepstakes etc. to be run at Ascot, Bath, Newmarket, York and other places. He also at times took part in races, for example riding Lord Clermont’s Rapid Roan in a Newmarket sweepstake at the second spring meeting in May 1775.

A crack shot, reputedly the best in the land, George was very knowledgeable about the field, publishing in 1814 his Colonel Hanger to all Sportsmen, and particularly to Farmers and Gamekeepers, a work that has stood the test of time and been recently reprinted. In it he provides useful tips on shooting a wide variety of game besides addressing the care of dogs and horses, ways to catch vermin etc.

As far as George’s career in the Guards was concerned, the wheels came off the waggon in early 1776. Promoted to lieutenant on February 20, he resigned his commission one month later. “It is,” he explains, “sufficient to say that I conceived myself most unjustly treated relative to a promotion that took place in the First Regiment of Foot Guards. Great parliamentary interest was the cause of it to the entire destruction of my promotion in a service to which I was most devoutly attached and of which I resolved to experience the substance, not the disgraceful empty shadow of parading about the streets of London with the outward flimsy insignia of a soldier ― a cockade and red coat. All my friends advised me to remain in the regiment and my worthy friend, that enlightened commander Sir William Draper, in particular advised me to do so. I never shall forget his words, ‘You are used very ill but you cannot contend against power. Put up with it and use it at some future period as a plea to be served.’ But I was too young to take advice and too haughty and high in blood tamely to brook an injury without resenting it or shewing all the indignation I felt on the occasion. Deaf to all advice and blind to my own interest, vexed, heated, and agitated with an honest consciousness of the wrongs I had suffered, I resolved on quitting the Guards and of serving in the Hessian troops in America.”

George made application to the Landgrave and learned the outcome while in the country. “In my way down to Andover in Hampshire, where I kept my hunters, I called on my old and intimate friend, Lord Spencer Hamilton, and imparted to him what I had done, in confidence of his secrecy. I kept this design of mine so profound a secret that it was not in the least known or suspected till one day, after hunting, while I was at dinner with my friend Lord Egmont and some other gentlemen at the Castle Inn, Marlborough, the waiter informed me that an express was arrived to me from the Hessian minister. After reading the contents, that he had received a dispatch from Hesse-Cassel in which His Serene Highness the Landgrave had appointed me a captain in His Corps of Jägers and had sent my commission to him, I threw the letter on the table for the company to peruse, which they did with the utmost astonishment. I set off for London the next day.” His commission ― in fact as a staff captain ― was dated January 18, 1778.

After being presented at Court as a Hessian officer, George two months later joined up with a convoy of Hessian troops bound for America. Escorted by naval ships under Rear Admiral Gambier, they sailed from Portsmouth on March 15.[17]

Bibliography

Angier, C. J. Bruce, “Memoirs of an eccentric nobleman,” London Society, 66 (1894), 137-52

Bloch, Ivan, Sexual Life in England Past and Present, translated by William H. Forstern (London: Francis Aldor, 1938)

The Complete Peerage of England, Scotland, Ireland, Great Britain and the United Kingdom extant, extinct or dormant (London, 1910)

Cruickshank, Dan, The Secret History of Georgian London (London: Random House Books, 2009)

Greig, Hannah, The Beau Monde: Fashionable Society in Georgian London (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013)

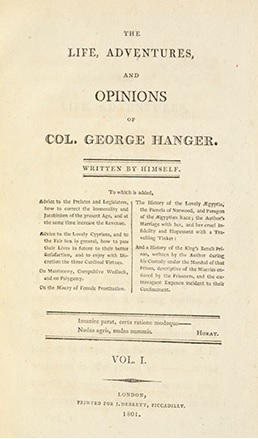

Hanger, George, The Life, Adventures, and Opinions of Col. George Hanger (London, 1801)

Highfill Jr., Philip, et al., A Biographical Dictionary of Actors, Actresses, Musicians, Dancers, Managers & Other Stage Personnel in London, 1660- 1800 (Carbondale, IL: Southern Illinois University Press, 1973)

Kelly, Ian, Beau Brummell: The Ultimate Dandy (London: Hodder and Stoughton, 2005)

A List of General and Staff Officers on the Establishment in North America (New York, 1783) in The Clinton Papers, William L Clements Library, University of Michigan

Lyte, Sir H. C. Maxwell, A History of Eton College, 1440-1884 (London: Macmillan & Co, 1889)

Melville, Lewis, The Beaux of the Regency (London, 1908)

Morning Chronicle and London Advertiser (London, 1772-8)

Naxton, Michael, The History of Reading School (Ringwood: Pardy & Son Printers, 1986)

Parsons, Martin, and Oakes, John, Reading School: The First 800 Years (London: DSM, 2005)

Russell, Gillian, Women, Sociability and Theatre in Georgian London (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007)

Stone Jr., George Winchester, The London Stage 1660-1800: Part 4, 1747-1776 (Carbondale, IL: Southern Illinois University Press, 1962)

Thorne, R. G., ed., The History of Parliament: The House of Commons 1790-1820 (Sparkford: Haynes Publishing, 1986)

Town and Country Magazine (London, 1772 and 1777)

Valentine, Alan, The British Establishment 1760-1784: An Eighteenth-Century Biographical Dictionary (Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press, 1970)

[1] One of the American Revolution’s most colorful characters, Hanger is barely known outside academic circles, and then only imperfectly. His unique military career comprised service in the British Foot Guards, the Hessian Jäger Corps, and a British American regiment commanded by Banastre Tarleton, besides acting as an aide-de-camp to Sir Henry Clinton. His personal life was equally diverse and adventurous.

[2] Approximately £5,000,000 in today’s money.

[3] In fact, three summers.

[4] Approximately £46,500 in today’s money.

[5] A haunt of thieves, vagabonds and common prostitutes.

[6] A reference to part of a work on Latin grammar written by William Lily (c 1468-1522) and used at Eton.

[7] Great impression.

[8] Popular drinking establishments outside the centre of Paris, which also served food and catered for dances.

[9] Duels.

[10] Bit player

[11] Seraglios

[12] A court running between Pall Mall and King Street, St. James’s. Virtually all its houses were high-class brothels, including Charlotte Hayes’ nunnery.

[13] Carlisle House in Soho Square, a risqué venue for concerts, gambling and exotic masquerades.

[14] Thais was the name of a Greek courtesan who became the wife of Ptolemy I of Egypt in c 335 BC.

[15] To transpose this and later sums in this chapter into present-day values multiply by a factor of 140.

[16] A character in John Gay’s The Beggar’s Opera.

[17] For George’s service in America, see Ian Saberton, “George Hanger ― His Adventures in the American Revolutionary War begin,” (January 30, 2017) and idem, “George Hanger ― His Adventures in the American Revolutionary War end,” Journal of the American Revolution (February 17, 2017).

5 Comments

Do you know anything about the monkeys Hanger would have with him?

I ran across this quote: “A contemporary described with disgust Hanger’s fondness for “introducing into the best apartments of the most respectable families, his cats, his dogs, and his monkeys, while revelling himself in every species of sensuality.”

Charles

Please see my third article in the trilogy on Hanger which is to be uploaded to the JAR in Feb. The second article will appear then or later this month.

Never heard of the guy, but I’d like to share a beer with him. Great story!

I am excited to find your article. Very few Americans even know of his name.

I have researched Hanger occasionally since the 1970s. During his challenge in October 1780, while in Charlotte, NC, George gave a gift that has been passed down through my family, along with his story, ever since. Hanger was wounded during the Charlotte ambush. George was later stricken with yellow fever while retreating from Charlotte ten days later. The proof; Hanger’s gift was given to the person who nursed his gun shot wound while he was in Charlotte.

Amazingly detailed series of articles, many thanks. I know Hanger through reading his autobiography many years ago and of course from his appearances in period caricatures. Just curious, does any manuscript material survive?