The American Revolutionary War was fought largely by armies on the North American continent, however, like waves in a pond the conflict inevitably rippled out across the Atlantic world. The flow of people, supplies, and information was crucial to waging war across the Atlantic, and they were linked by who could control the sea. While studies of the use of naval power during the American Revolution abound, an in depth consideration and focus on the use of privateers during this time finally is receiving fresh scholarly attention in the twenty-first century.[1] Yet, for all the studies examining privateering during the American Revolution thus far, one aspect remains to be explored more fully: their role in the slave trade.

Privateers were privately armed ships legally sanctioned by a government to attack the merchant vessels of a nation with which the sponsoring country was at war. Privateering commissions, the documents issued by governments that granted privately owned ships the right to be armed and outfitted for these types of cruises, often stipulated the vessel size, crew number, and basic rules they had to follow in order to have a legitimate claim on captured vessels. Captured vessels, or prizes, were to be determined legitimate or not by prize courts or vice admiralty courts. Similarly, letters of marque were also issued by governments to authorize merchant ships to seize enemy prizes they came across during a voyage. Unlike commissions, letters of marque primarily still functioned as merchant vessels hauling cargo while privateers were specifically outfitted as warships for capturing prizes. Either way, the value of the captured ship and cargo was shared by the privateer owners and crew.[2] The practice of commerce raiding was a maritime activity throughout the eighteenth century. The outbreak of the American Revolutionary War was an opportunity for privately armed ships to obtain permission from states, the Continental Congress, and Great Britain to wage war on their enemy’s trade. Later as Spain, France, and the Netherlands entered the war, so too did they bring more privateer vessels into the “prize game.”[3]

Maritime historian David Starkey noted that during the American Revolution British privateering, in particular, reached “its apogee, by most measures, for the ‘long’ eighteenth century as a whole.”[4] While earlier histories of the American War of Independence treated privateering as a quasi-legal activity that was peripheral to the main theater, maritime historians have shown it was in fact widespread and a major wartime pursuit.[5] All the belligerent nations that participated in the American Revolution issued commissions to privateers to attack merchant vessels in order to harm or improve economic power, hamper or bolster political will, and increase or diminish access to resources.

For the Americans, privateers were particularly important since they captured desperately needed supplies, such as firearms, gun powder, ammunition, and goods. They also seized ships, gathered intelligence, and at least for a time effectively became the de facto American naval force since the Continental Navy remained relatively weak throughout the war. Even early in the war, during the siege of Boston in 1775 when Gen. George Washington was desperate for supplies, it was ultimately an American privateer ship that captured a British military supply vessel and delivered thousands of arms for use by the American army.[6] Additionally, the British were forced to redirect ships from convoy or blockade duties to police the privateers who operated in the Caribbean and brought ruin to West Indian traders.[7] Some estimates put American privateers as being responsible for taking 16,000 British seamen as prisoners and capturing 3,386 British ships, with an estimated value of $66 million.[8]

For the British, privateering vessels were an important aspect of naval operations as well. The British faced a major land war in North America that required the logistics of their navy to convey and transport supplies and men over 3,000 miles of water. With the entrance of the Dutch, French, and Spanish, Britain was forced to stretch its navy to protect its colonial interests throughout North America, the Caribbean, Mediterranean, and the Far East. With its resources spread out across the Atlantic world and its navy on the defensive, privateer vessels allowed the British to be on the offensive. Privateers also opened up opportunities for British merchants who suffered from the declining economic situation due to the loss in trade.[9]

Historians in recent years have appreciated how privateers shaped the American, British, and Spanish war efforts throughout the Age of Revolutions.[10] While from a legal standpoint privateers were widely deployed and perhaps necessary for smaller naval powers, they were not always seen in a positive light or on equal terms with other revolutionary actors. One of the reasons for privateers being seen as less patriotic compared to other actors in the Revolution is because they were often perceived as fighting for their own self-interests of making a profit. Individual privateersmen could potentially make small fortunes from a single cruise, but that depended on their success at capturing prizes and their rank on the ship.[11] Some contemporary Americans viewed privateers as taking desperately needed manpower away from the army and navy and occasionally acting like nothing more than pirates.[12] Lucy Knox, the wife of American Gen. Henry Knox, wrote to her husband that she did “not like privateering,” and that often property is taken from “innocent persons, who have nothing to do with the quarrel – [it] appears to me to be very unjust.”[13] Although clearly at odds with his wife’s conscience, Henry Knox invested their money in a privateer cruise a month after she wrote him this letter. Several other prominent American military officers, politicians, and shipping merchants invested their own money in privateer cruises during the war, and some made fortunes from these investments.[14]

Of course not all privateers were simply war profiteers. In some instances a lack of other sailing opportunities because of wartime disruption limited available options.[15] Mary Port Macklin describes how her life was turned upside down while living in Charleston when the war broke out. In her diary Mary wrote that she emigrated from England to Charleston in 1775 with her husband Jack Macklin where they operated an eatery for three years. After refusing to take an oath of fidelity to the revolutionary cause when the British Fleet arrived in Charleston harbor in 1778, her husband was thrown into jail and all their property was seized and sold. Eight months later they were sent as Loyalists to St. Augustine. When they arrived they had no money or work, so her husband “took the command of the Privateer named the Polley.”[16] Undoubtedly not all privateers had just their own self-interest at heart. Wills written by privateers before they left on cruises demonstrate that they had families back at home whom they were concerned about. David Harrison, a British mariner from Liverpool belonging to the privateer Sart, set up his last will and testament before his cruise in 1782. In his will he left his “dear wife Ellen Harrison … all wages at prize money bounty money and all other sums of money and all goods chattels cloaks and etc.”[17]

Nonetheless, making a profit remained an important motivation even among the patriotic.[18] The American privateer Christopher Prince wrote that during the Revolution he had “two motives in mind, one was for the freedom of my country, and the other was the luxuries of life.”[19] As Paul Gilje has clearly demonstrated, in many cases joining a privateer ship was not for patriotic reasons at all, but rather for the better pay.[20] In fact, some of the proceeds from prizes they made during the American Revolution included engaging in the slave trade.

Historians documented that from the sixteenth through the nineteenth centuries privateers in general were active agents in the entangled world system of the Atlantic slave trade. Linda Heywood and John Thornton found that the first Englishmen to bring Africans to the Americas as slaves were in fact privateers.[21] David Head demonstrated that privateers remained involved in this activity well after the foreign slave trade was banned in 1808.[22] Nevertheless, to date there appears to be no comprehensive examination of the role privateers during the American Revolution played in the Atlantic slave trade.[23] Historians have documented the practice of arming slaves to fight on both sides, and about a thousand known black slaves served on American naval and privateer ships during the war.[24] Going to sea in general offered enslaved black sailors some forms of freedom, and they served on many types of vessels throughout the eighteenth century Atlantic world including whalers, fishing ships, merchant vessels, naval warships, and even slavers.[25] In fact, at least half of the men sailing in Bermudian vessels on the eve of the American Revolution were enslaved people of African descent. According to historian Michael Jarvis these enslaved sailors “propped up the operations of Bermuda’s merchant fleet.” [26]

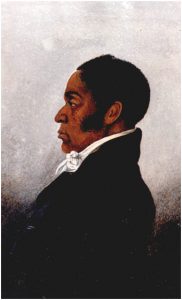

However, the outbreak of the war and issuing of privateering commissions could work for or against both free and enslaved people of African descent. James Forten, a free African-American who joined a privateer crew in 1781 when he was fourteen, feared that if he was captured he would be sold as a slave in the West Indies since “rarely … were prisoners of his complexion exchanged.”[27] His worries were not without grounds. In one particular case a group of enslaved black Bermudian sailors who made up the crew of a British privateer ship were sold when they were captured. In 1780 an American sailor named Joseph Bartlett serving on board a British privateer ship out of Bermuda was captured by an American letter of marque from Philadelphia. Afterwards, Bartlett joined the American crew and bragged that his fifty former slave shipmates were sold for a “hefty price” in the Havana slave market.[28] In her journal Mary Macklin wrote that part of her husband’s first prize share included “3 negro lads,” and the second “prise he sherd for his part” an enslaved couple named Robert and Nancy.[29] These were not isolated incidents; privateers took an active role in the slave trade.

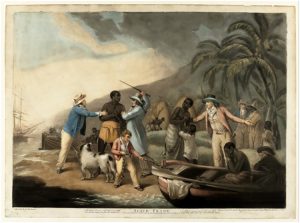

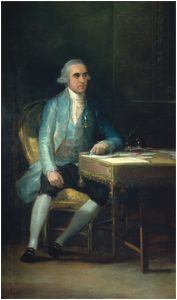

Since slaves were considered property, terrestrial-based revolutionary actors engaged in this practice as well. After all, slaves were considered spoils of war.[30] While some accounts of slaves becoming crew on board privateers suggests agency, like their counterparts on land privateers did capture and sell slaves for a profit to a notable degree. This included capturing slave ships at sea like the cases mentioned above, as well as amphibious raids on plantations. Don Francisco Saavedra de Sangronis was a Spanish soldier and government official sent on a mission by General Bernardo de Galvez during the American Revolution to help plan to retake Pensacola, Florida, and eventually to capture Jamaica. He spent over a year in Jamaica after his ship was captured by the British and kept a diary of his experiences during the war. Of particular interest is a story he related of a British officer complaining to him of how Spanish corsarios, or privateers, frequently sailed from the port of Trinidad in canoes “authorized with the royal letter of marque” and raided plantations in British Jamaica for slaves. They then smuggled these slaves to Cuba and sold them. [31] In 1777 two plantations on the island of Tobago owned by Charles Gustavas Meyers and Henry Kelly were raided by an American privateer named Paschall Bonavita. When Bonavita and his crew raided the Meyers and Kelly plantations they stole a small schooner at anchor as well as thrity-seven black slaves and “2 Carib Indians born in the Island of St. Vincents.” They sold the slaves to their Spanish contacts in Trinidad.[32] Spanish and American privateers reportedly raided plantations at New Smyrna in East Florida for slaves as well.[33] In 1781 a British privateer captured thirty slaves from an American plantation in Westmoreland, and there were several other incidents of both American and British privateers raiding plantations for “slave loot” as well.[34]

The Atlantic slave trade declined during the American Revolutionary War and in some years decreased by half. Nevertheless, slavers continued to transport “captive cargoes” throughout the conflict.[35] A British slave ship captain noted that in the year 1777 “The trade [to the Gold Coast of Africa] in general has suffered greatly since I have known it, both as to the difficulty in obtaining slaves, and the price at which they are purchased.”[36] Contemporaries observed that in some areas of the Atlantic world the prices for slaves declined while in others they increased dramatically. In 1788 Thomas Clarkson wrote that during the American war “while the price of a slave was as low as seven pounds on the coast, and as high, on an average, as forty-five in the colonies, the adventurer, who escaped the ships of the enemy, made his fortune.”[37] The Annals of Commerce, Manufactures, Fisheries and Navigations listed the average price for slaves from the years 1764 to 1788 in Africa as eight to twenty-two pounds Sterling compared to twenty eight to thirty five pounds Sterling in the West Indies.[38] In general slave prices increased throughout the war and created abnormally large profits in the trade.[39] Even though a quarter or more of slave vessels were captured during wartime, the demand for slaves in the Americas made it a risky but worthwhile business venture.[40]

In her study of British Admiralty records, E. Arnot Robertson wrote that it made no difference for slaves who were rerouted from capture, “except that they worked till they died in Jamaica, and not in Barbados or the Southern States of America.”[41] Yet, one might argue that the trauma of capture alone certainly mattered to “the experience of the historical subjects” involved in such instances.[42] Robertson wrote this book in 1959, and since that time historians have demonstrated to some extent it mattered where the enslaved ended up geographically at least in terms of individual experience, and thus for the lives of their descendants. [43] We must remember, as Vincent Brown stresses, that numbers alone “cannot represent the wrenching personal trials endured by the enslaved.”[44]

Nonetheless, according to The Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade Database (TASTD), 480,929 slaves embarked on 1,551 voyages across the Atlantic world during the years of the American Revolutionary War from 1775-1783.[45] Of these, 31,768 slaves were captured on 107 different voyages by naval and privateer vessels during the course of the conflict. These slaves were rerouted from their intended point of disembarkation to ports allied to the flag the privateer vessel flew under, or where supporters or agents could secure their anchorage. Utilizing the TASTD variable query of slave ships captured specifically by a “pirate/privateer,” shows that 1,690 slaves were captured by six different privateer vessels from 1775-1783. By using various primary and secondary source materials and cross referencing them with the voyage outcomes recorded as captured in the TASTD, it is clear that the number of slaves captured by privateers during the years of the American Revolution actually exceeds what the TASTD currently shows. In fact, at least 8,519 slaves were captured on 43 privateer cruises during the American Revolution. [46] This is nearly twenty-seven percent of the slaves listed as captured by vessels in the TASTD throughout the war.

Part of this discrepancy is because some of the slave vessels captured by privateers recorded in the TASTD are listed under the variable queries of “unknown” or “captor unspecified.” The privateers recorded were predominantly American or British, but also include French and Spanish (26 American ships, 9 British, 1 French, 2 Spanish, 4 unspecified). America and Britain should be expected to have the highest numbers of privateers since they were the two main belligerents during the conflict and were likely responsible for issuing most of the commissions. Also, the sources utilized here are primarily Anglo-American. If Dutch, French, and Spanish sources are included the overall number of privateer ships involved in transporting and selling captive cargoes during the war will undoubtedly increase.[47]

Nearly half the American privateer ships recorded in this study took their captured prizes with cargoes, including slaves, to the French island of Martinique. Others sailed to various ports in North America (New Orleans, Philadelphia, Connecticut, South Carolina, Georgia) or other French and Spanish Caribbean islands (Haiti and Trinidad). In contrast, the British privateer vessels recorded in this study took almost all their captured prizes with cargoes including slaves to Jamaica or the West Indies (a few were adjudicated in British East Florida in St. Augustine). The highest number of slaves captured by a privateer on one voyage was 697, and the lowest number of slaves recorded captured by a privateer on a single voyage was one.[48]

When compared to overall operations, privateer ships that sailed on cruises during the American Revolution did not regularly capture slave ships or raid plantations. At least qualitatively, the bulk of the prize ships privateers captured carried goods, raw materials, or war contraband. [49] Yet, for the thousands of enslaved individuals who found themselves onboard privateer ships against their will, the actions of privateers certainly mattered because being captured added to the trauma of their voyage and ultimately determined their final place of disembarkation. Although the number of slaves imported as “prize cargo” was small compared to the overall number of enslaved people shipped during the conflict, new questions should be asked pertaining to the role privateers played in the slave trade during the war.[50]

The American War of Independence is often remembered by the public as a revolution led by colonial patriots who fought for liberty against oppressive British masters.[51] Yet, some of these revolutionary actors who participated in the conflict, such as privateers, were at least partially motivated to fight for the large profits they could receive from prizes, and not just for the ideals of “liberty and equality.” Moreover, some of these same revolutionary privateers helped deny individual freedom to others through their role in the slave trade by stealing and selling “captive cargoes.” While some politicians, generals, merchants, and even common Jack Tars certainly lost all they had during the war, others profited handsomely from the human beings and property they captured and sold throughout the conflict.

[1] Kylie Alder Hulbert, “Vigorous and Bold Operations: The Times and Lives of Privateers in the Atlantic World During the American Revolution,” Ph.D. dissertation, University of Georgia, 2015. E.J. Martin, “The Prize Game in the Borderlands: Privateering in New England and the Maritime Provinces, 1775-1815,” Ph.D. dissertation, University of Maine, 2014. James Richard Wils, “In behalf of the continent”: Privateering and Irregular Naval Warfare in Early Revolutionary America, 1775-1777,” Ph.D. dissertation, East Carolina University, 2012. Michael J. Crawford, “The Privateering Debate in Revolutionary America,” The Northern Mariner, XXI No. 3 July 2011, 219-234. Sarah Vlasity, “Privateers as Diplomatic Agents of the American Revolution 1776-

1778”, PhD dissertation, Department of History, University of Colorado at Boulder, 2011. Robert H. Patton, Patriot Pirates: The Privateer War for Freedom and Fortune in the American Revolution (New York: Pantheon Books, 2008). Richard Pougher, “’Averse … to remaining idle spectators’: The Emergence of Loyalist Privateering During the American Revolution, 1775—1778,” Ph.D. dissertation, The University of Maine, 2002.

[2] Donald A Petrie, The Prize Game: Lawful Looting on the High Seas in the Days of Fighting Sail (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1999). Matthew Taylor Raffety, The Republic Afloat: Law, Honor, and Citizenship in Maritime America (London: The University of Chicago Press, 2013), 31. For a thorough discussion on the anachronistic meaning between piracy and privateering, the difference between commission and letters of marque, and the limits of government authority on the practice see Guy Chet, The Ocean is a Wilderness: Atlantic Piracy and the Limits of State Authority, 1688-1856 (Boston: University of Massachusetts Press, 2014). For an overview of the historic context and use of privateering in Europe and the Americas see Janice E. Thomson,

Mercenaries, Pirates, and Sovereigns: State-Building and Extraterritorial Violence in Early Modern Europe (Princeton University Press, 1994), 21-68. Also see Alejandro Colas and Bryan Mabee, ed., Mercenaries, Pirates, Bandits and Empires: Private Violence in Historical Context (New York: Columbia University Press, 2010).

[3] Carl Swanson, Predators and Prizes: American Privateering and Imperial War, 1739-1748 (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 1991). Patrick Crowhurst, The French War on Trade: Privateering 1793-1815 (Leicester: Scolar Press, 1989). David J. Starkey, British Privateering Enterprise in the Eighteenth Century (Exeter: University of Exeter Press, 1990).

[4] Starkey, British Privateering Enterprise, 194.

[5]Edgar Stanton Maclay, A History of American Privateers (New York: Freeoirt, 1962). Wils,”In Behalf of the Continent,” 75-93. Michael Scott Casey, “Rebel Privateers—the Winners of American Independence,” MA thesis, U.S. Army Command and General Staff College, 1990.. rom ships, Results ofe, 1990),ss, 1991). r cruises during the American Revolution. ere primarily British and American. nts d

[6] David McCullough, 1776 (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2005), 64.

[7] Selwyn H. H. Carrington, “The American Revolution and the sugar colonies, 1775-1783,” in Jack Greene and J. R. Pole, A Companion to the American Revolution (Oxford: Blackwell Publishing, 2004), 515-517. Also see Andrew Jackson O’Shaughnessy, An Empire Divided: The American Revolution and the British Caribbean (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2000), 154-157. Nathan Miller, Sea of Glory: A Naval History of the American Revolution (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1992), 261.

[8] Miller, Sea of Glory, 260-261.While Miller devotes several pages to privateering, he only mentions the slave trade a single time in the book. Starkey, British Privateering Enterprise, 200, 221, 279.

[9] Starkey, British Privateering Enterprise, 193-195. See also John O. Sands, “Gunboats and Warships of the American Revolution,” in George Bass, ed., Ships and Shipwrecks of the Americas: A History Based on Underwater Archaeology (London: Thames and Hudson, 1996), 149-168.

[10] David Head, Privateers of the Americas: Spanish American Privateering from the United States in the Early Republic (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2015). Matthew McCarthy, Privateering, Piracy and British Policy in Spanish America, 1810-1830 (Suffolk: Boydel Press, 2013). Edgardo Perez Morales, “Itineraries of Freedom: Revolutionary Travels and Slave Emancipation in Colombia and the Greater Caribbean. 1789-1830,” Ph. D dissertation, University of Michigan, 2013. Edgardo Perez Morales, El gran diablo hecho barco. Corsarios, esclavos y revolución en Cartagena y el Gran Caribe. 1791-1817 (Bucaramanga: Universidad Industrial de Santander, 2012). Vanessa Mongey, “Cosmopolitan Republics and Itinerant Patriots: The Gulf of Mexico in the Age of Revolutions (1780s – 1830s),” Ph. D dissertation, University of Pennsylvania, 2010.

[11] See Christopher Prince, The Autobiography of a Yankee Mariner: Christopher Prince and the American Revolution, ed. Michael Crawford (Washington D.C.: Potomac Books, 2002), 144-145, 162. See John Palmer Papers, “Sloop REVENGE (Privateer) abstract log, Jul.-Sep. 1777, and journal Feb.-Jun. 1778, Joseph Conkling, master; contains Articles of Agreement for privateering voyage,” G. W. Blunt White Library, Mystic Seaport Collection, Coll. 53 – Box 1, Folder 12 , 39, accessed http://library.mysticseaport.org/manuscripts/coll/coll053.cfm. John Palmer was a Revolutionary War soldier and mariner from Stonington, Connecticut. He served on the Revenge on two cruises lasting four months each under Captain John Conkling spanning 1777-1778. In his diary he noted that “things taken the second cruise with Captain Conkling on and brought home into the family”: 13 pounds of coffee, 9 pounds chocolate, 9 pounds of sugar, 2 ¼ gallons molasses, and 1 gallon rum valued at 21 pounds 12 shillings. See “John Palmer Diary,” John Palmer Papers, G. W. Blunt White Library, Mystic Seaport Collection 53, Box 1, Folder 10, 22, accessed http://library.mysticseaport.org/manuscripts/coll/coll053.cfm

[12] See Hurlbert, “Vigorous and Bold Operations,” 13, 164-220.

[13] Lucy Knox to Henry Knox, March 18, 1777, Gilder Lehrman Collection GLC02437.00553, https://www.gilderlehrman.org

[14] George Washington, Benjamin Franklin, John Hancock, Henry Knox, Jonathan Jackson, Tristan Dalton, and William Pickman are just a few of these American leaders who made investments in privateering enterprises during the American Revolution. See Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History Collection GLC01411 for letters, court cases, and receipts demonstrating these specific individuals’ business ventures with privateering. https://www.gilderlehrman.org/collections, accessed September 9, 2016. Also see Kevin Philips, Wealth and Democracy: A Political History of the American Rich (New York: Broadway Books, 2003), 13-14.

[15] Daniel Vickers and Vince Walsh, Young Men and the Sea: Yankee Seafarers in the Age of Sail (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2007), 164-165.

[16] Mary Port Macklin, Mary Port Macklin Journal, 1823, P.K. Yonge Library of Florida History, Special Collections, Diary Box 16, 22-23, accessed September 12, 2016, http://ufdc.ufl.edu/AA00017213/00001 .

[17] “Will of David Harrison otherwise George Greaves, Mariner now belonging to the Sart Privateer of Liverpool , Lancashire,” July 31, 1782, The National Archives, Kew, Wills and probate, PROB 11/1093/396.

[18] Hurlbert, “Vigorous and Bold Operations,” 164-165.

[19] Prince, The Autobiography of a Yankee Mariner, 210. Also see Crawford, “The Privateering Debate in Revolutionary America,” 225-226

[20] For more discussion on sailors who sought out privateer service, especially to earn a living or make a “small fortune” during the American Revolution, see Paul Gilje, Liberty on the Waterfront: American Maritime Culture in the Age of Revolution (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2007), 106-116. Sometimes the line between public or private ventures on ships outfitted for cruises against the enemy were confused and ill-defined in wartime. See Louis Arthur Norton, “America’s Unwitting Pirate: The Adventures and Misfortunes of a Continental Navy Captain,” CORIOLIS, Volume 6, Number 1, 2016.

[21] Linda M. Heywood and John K. Thornton, Central Africans, Atlantic Creoles, and the Foundation of the Americas, 1585-1660 (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2007).

[22] David Head, “Slave Smuggling by Foreign Privateers: Geopolitical Influences on the Illegal Slave Trade,” Journal of the Early Republic, 33, 2013.

[23] There are a few studies that mention privateers capturing slaves, but do not attempt to more fully explore the subject. See Joseph Inikori, Africans and the Industrial Revolution in England: A Study in International Trade and Economic Development (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002), 253-265. See Hurlburt, “Vigorous and Bold Operations”. See E. Arnot Robertson, The Spanish Town Papers: Some Sidelights on the American War of Independence (New York: Macmillan Company, 1959), 128-143. See Benjamin Quarles, The Negro in the American Revolution (Williamsburg: The University of North Carolina Press, 1996).

[24] Philip D. Morgan and Andrew Jackson O’Shaughnessy, “Arming Slaves in the American Revolution,” in Christopher Leslie Brown and Philip D. Morgan, ed. Arming Slaves: From Classical Times to the Modern Age (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2006), 198. Black slaves also served aboard British privateer vessels during the American Revolution. See Michael Jarvis, “Maritime Masters and Seafaring Slaves in Bermuda, 1680-1783,” The William and Mary Quarterly 59, no. 3 (2002): 585-622. See Cassandra Pybus, Epic Journeys of Freedom: Runaway Slaves of the American Revolution and Their Global Quest for Liberty (Boston: Beacon Press, 2006), 29, 237. Also see Quarles, The Negro in the American Revolution, 91-93.

[25] W. Jeffrey Bolster, Black Jacks: African American Seamen in the Age of Sail (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1997). Emma Christopher, Slave Ship Sailors and Their Captive Cargoes, 1730-1807 (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2006), 51-90, 60-61.

[26] Michael J. Jarvis, In the Eye of All Trade: Bermuda, Bermudians, and the Maritime Atlantic World, 1680-1783 (Williamsburg: University of North Carolina Press, 2012), 149.

[27] Julie Winch, A Gentlemen of Color: The Life of James Forten (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005), 43.

[28] Gilje, Liberty on the Waterfront, 116. For another case of black sailors on a British privateer being sold as slaves in Maryland see Quarles, The Negro in the American Revolution, 107.

[29] Macklin wrote that Robert and Nancy became their house slaves, while the three “negro lads” went with her husband. Mary Port Macklin Journal, 24.

[30] Quarles, The Negro in the American Revolution, 107, 156.

[31] Saavedra De Sangronis Francisco, and Francisco Morales Padrón, Journal of Don Francisco Saavedra De Sangronis during the Commission Which He Had in His Charge from 25 June 1780 until the 20th of the Same Month of 1783 (Gainesville: University of Florida Press, 1989), 45-47.

[32] See Michael J. Crawford, Naval Documents of the American Revolution Volume 10 (Washington D.C., U.S Government Printing Office, 1994), 277-279.

[33] Jennifer Snyder, “Revolutionary Repercussions: Loyalist Slaves in St. Augustine and Beyond,” in In Jerry Bannister and Liam Riordan, Loyal Atlantic: Remaking the British Atlantic in the Revolutionary Era (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2012), 174-176.

[34] Quarles, The Negro in the American Revolution, 118, 131-132.

[35] According to The Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade Database, before the war began in the year 1775 over 92,000 slaves embarked on voyages. As the Revolutionary War continued this number declined dramatically, reaching its lowest level during the war in 1779 with 37,758 slaves embarking on voyages for the year. The number of slaves embarking on voyages did not recover to prewar levels until after the war ended. In 1784 the number of slaves embarking on voyages rapidly increased to its highest number for a year in over three decades to 104,364. http://slavevoyages.org/assessment/estimates . The slave trade declined by a quarter in the early years of the war and twelve out of thirty Liverpool slave companies went out of business before 1778. See O’Shaughnessy, An Empire Divided, 166. Some vessels involved in the slave trade before the American Revolution began did in fact fit out to become privateers during the war. See David Eltis and David Richardson, Atlas of the Transatlantic Slave Trade (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2010).

[36] “Minutes of Enquiry into Administration of the West African Trade: Volume 84,” in Journals of the Board of Trade and Plantations: Volume 14, January 1776 – May 1782, ed. K. H. Ledward (London: His Majesty’s Stationery Office, 1938), 126-146. British History Online, http://www.british-history.ac.uk/jrnl-trade-plantations/vol14/pp126-146, accessed September 10, 2016.

[37] Thomas Clarkson, An Essay on the Impolicy of the African Trade (London: J. Phillips, 1788), 25.

[38] David Machperson, Annals of Commerce, Manufactures, Fisheries, and Navigation Vol. IV (London: Nicols and Son, 1805), 153.

[39] David Eltis, Lewis, and Richardson, “Slave Prices, the African Slave Trade, and Productivity in the Caribbean, 1674-1807,” The Economic History Review, New Series, 58, no. 4 (2005): 679-686. Elizabeth Donnan wrote that “The information about the price of slaves during the early years of the Revolution is curiously conflicting.” See Elizabeth Donnan, Documents Illustrative of the History of the Slave Trade to America: Volume II: The Eighteenth Century (New York: William S. Hein & Col., 2002), 554. The price of goods in general fluctuated geographically during the American Revolution. See O’Shaughnessy, An Empire Divided, 160-167. Also see Mary M. Schweitzer, “The Economic and Demographic Consequences of the American Revolution,” in Greene, A Companion to the American Revolution, 559-577. Joseph Inikori, “Measuring the unmeasured hazards of the Atlantic slave trade: documents relating to the British trade,” Revue Francais D’Histoire D’Outre Er 83 (September 1996), 88.

[40] See David Eltis, Lewis, and Richardson. “Slave Prices.” According to one study, two thirds of the British slave ships lost were captured by an enemy nation during wartime. See Christopher, Slave Ship Sailors and Their Captive Cargoes, 75.

[41] Robertson, The Spanish Town Papers, 135.

[42] See Vincent Brown, Reaper’s Garden: Death and Power in the World of Atlantic Slavery (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2008), 29.

[43] Ibid, 48-57. See Ira Berlin, Generations of Captivity: A History of African-American Slaves (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2003), 55.

[44] Brown, Reaper’s Garden, 29.

[45] This is according to the summary statistics for the years 1775-1783 on the The Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade Database. In 1775 the war at sea was not yet significant at that time, and the several months of that year when the war was not impacting numbers of the slave trade do somewhat skew the results. This database is the most comprehensive source on slave voyages ever compiled by researchers. The web resource allows researchers to query specific variables and dates to analyze over 34,000 slave voyages that transported over 10 million Africans to the Americas. David Eltis, et al. The Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade Database., http://www.slavevoyages.org.

[46] Three primary sources were utilized for this purpose. These include the Naval Documents of the American Revolution, Lloyd’s List, and incidents reported in British and American colonial newspapers and court records. Clark, William Bell, Ernest McNeill Eller, et al. Naval Documents of the American Revolution. Volumes 1-12 (Washington: U.S. Govt. Print. Off., 1964-2013). Lloyd’s List 1774-1775, 1775-1776, 1776-1777, 1777-1778, 1778-1779, 1779-1780, 1780-1781, 1781-1782, 1782-1783, 1783-1784 (Westmead, Great Britain. Gregg International, 1969), https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/000549597. Newspaper Archives 1690-2010, NewsBank and/or the American Antiquarian Society, 2004, geneaologybank.com. A database of privateers mentioned in these sources as capturing slaves was compiled with relevant information recorded by the author in a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet. Other primary sources utilized include court records, ship logs, and diaries.

[47] Moreover, the number of slaves captured by privateers might easily double from what this study documented. According to a report filed in 1777 by the Board of Trade, which investigated the African Company of Merchants after a request from the House of Commons, “During the last two years, the colonies did not receive 16,000 annually from all parts of Africa, even when any of those purchased there escaped, being taken by American privateers on their passage to the West Indies.” See Donnan, Documents Illustrative of the History of the Slave Trade, 553.

[48] No. 1036, February 26, 1779, Lloyd’s List 1779 & 1780 (Westmead: Gregg International Publishers, 1969). Henry Yonge, Court of the Vice Admiralty, “Claim Made on the Sloop Lucky Strike,” 1779, The Gilder Lehman Institute of American History, GLC01411.10: Legal Documents relating to captured American Privateers, 1776-1779.

[49] When the American sailor Jacob Nagle served aboard two different privateer vessels from April 1780 to November 1781, he claims they took dozens of prizes. Although Nagle identifies some of types of the cargo and items they captured from ships, he does not mention slaves being onboard any of these prizes. This was probably the typical case for most privateer cruises during the American Revolution. Jacob Nagle served as a sailor for both the British and American navies throughout his decade’s long career. Chapter two in this published diary cover his service on board an American privateer ship from April 1780 to November 1781, providing a unique first-hand account on life on privateer cruises during the American Revolutionary War. See Jacob Nagle, The Nagle Journal: A Diary of the Life of Jacob Nagle, Sailor, From the Year 1775 to 1841, John C Dann, ed. (New York: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1988), 15. Christopher Prince does not mention capturing slaves on board prizes in his account of the privateer cruises he served on from 1777-1781 either. Neither do Christopher Hawkins (American privateer ship Eagle) or Andrew Sherburne (American privateer ships Ranger and Greyhound). See Christopher Hawkins and Charles I. Bushnell, ed. The Adventures of Christopher Hawkins (New York: 1864) and Andrew Sherburne, Memoirs of Andrew Sherburne: A Pensioner of the Navy of the Revolution, 2nd edition (Providence: H.H. Brown, 1831).

[50] One important question to research further is what was the economic impact of these slave cargoes on the privateering enterprise (e.g. recruiting), privateering ports, and the American war effort? This was raised by Dr. Guy Chet in a comment on an earlier draft of this paper. Lydia Towns noted in an unpublished paper that “Historians of the transatlantic slave trade have been lax in evaluating the impact of piracy on the transatlantic slave trade during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, relegating phenomena of piracy to a side note in many of their texts.” Lydia Towns, “English Privateers and the Transatlantic Slave Trade,” https://www.academia.edu/14696017/English_Privateers_and_the_Transatlantic_Slave_Trade

[51] Gary Nash, The Unknown American Revolution: The Unruly Birth of Democracy and the Struggles to Create America (New York: Penguin Group, 2006), xiv-xv.

6 Comments

Excellent piece on a topic that often gets glossed over. Thank you!

Hi Eric!

Thanks for the compliment! I recently came across a couple sources that do touch on the topic that I wish I had included in this piece . One is by Charles Foy titled, “Ports of Slavery, Ports of Freedom: How Slaves Used Northern Seaports’ Martime Industry to Escape and Create Trans-Atlantic Identities, 1713-1783.” Foy found that during the American Revolution one hundred and eighty-seven “colored mariners” were condemned as prize slaves in Vice Admiralty courts.

Another source that I recently became aware of that includes an excellent treatment of privateers during the American Revolution is Sam Wills “The Struggle for Sea Power: A Naval History of the American Revolution.”

Both are definitely worth the read!

Very interesting article. Some excellent and long overlooked information.

Don’t forget when you are discussing the topic of patriotism vs. profit as motivation, the two could often blend quite easily. (When someone signs up for the armed forces today we don’t think them unpatriotic for taking advantage of educational and vocational opportunities.) We have plenty of stories and journals from the revolutionary era where men were serving in the Continental Navy or Army (For example Glover’s Marblehead men) that when their terms of service were up changed to privateering because they saw it as a way to continue serving the cause and make their fortunes. After all the service in the Continental Navy was running the same risks without the same financial reward. Why not at least have the possibility of reward as well if you are already hazarding your life?

Hi Daniel,

I definitely agree with you, patriotism and profit could and often did blend together for actors. Christopher Prince’s quote really highlights that. Thanks for pointing that out!

I should add, however, that my review of privateer recruiting advertisements definitely shows how much emphasis was placed on making a fortune over service to country. While I certainly wouldn’t argue that this represents what privateers in general thought, it does shed some light on at least what captains and commanders thought were the main reasons for sailors to join their crusies.

For example, I reviewed classifieds in colonial newspapers from 1775-1781 and found 23 ads for sailors to join privateer cruises. Out of the 23 ads I recorded two main incentives: 1) fortune and/or 2) for country (i.e. service to king or to aid U.S.). Out of those 23 ads 14 had fortune listed, while only 6 included the incentive to serve country. Out of the 14 that listed fortune as a primary incentive only five of those also included service to country.

Interestingly, one included serving the sailors grog if they signed up, and another mentioned “better treatment” on board privateer ships.

I wasn’t able to include this in the original draft due to word count limitations, but thought I would mention it.

I meant reviewed colonial newspapers from 1775-1783.