Even under the strange, somewhat inept leadership of Loyalist Col. John Moore, the task of hampering Spartanburg’s Fair Forest role as a Patriot stronghold should have been straightforward. What could not have been known is what would happen when the frontier’s best sharpshooter teamed up with three lovely, most remarkable of women along with a lad of twelve years. This was one night where the Revolutionary War hype found often in the early Romanized histories almost equals what really happened.

The earliest settlers to the Fair Forest area of Spartanburg, South Carolina were eight Lancaster, Pennsylvania families who came upon a much different place than we see today. Only in Croft State Park, the best candidate for seeing what the Forest was once like, and still a beautiful place to visit, can now be glimpsed a place described as “the most delightful, as well as the most fertile in the world.” [1] The forests were said to be “imposing, the trees were large and stood so wide apart that a deer or buffalo could be seen at a long distance; the grasses and pea vines occupied the place of the young, scrubby growth of the present day.”[2] When he first saw the forest, James Mcilwaine, one of those dour, taciturn no-nonsense Presbyterians, could not contain himself, bursting forth in uncharacteristic eloquence. It was, he said, “a beautiful valley … lofty trees … a meandering stream … The rays of the declining sun shed their departing beams on the tree-tops that waved … in the evening breeze … What a Fair forest this!”[3]

Into this forest came one of the first families of the frontier American Revolution. Among its members were Jane Black Thomas and her son-in-law, Josiah Culbertson. Jane was married to John Thomas and Josiah to their daughter, Martha. The Thomas family settled where two creeks – the Kelsey (Kelso) and the Fair Forest – come together. Because Col. John Thomas, Sr. was among the most influential men in the area, his home quickly became a social and cultural center, a place to meet. Before it became too dangerous, militia musters were held there, neighbors gathered to hear news and to discuss what must be done; even weddings took place. Today we debate where this substantial plantation house might once have stood – no one knows now its exact location – and whether or not it was more than just a fortified log cabin. But in February, 1779 it was a place where being just the right kind of people in the right place, at the right time, determined how something involving a score of armed men, perhaps more than one hundred, would end.

On a bitterly cold night in February, 1779 a group of Tory militia — the number ranges wildly from less than ten to more than one hundred and fifty men depending on the source – faced one of the best, if not the best, Patriot frontier marksmen of the Revolutionary War, who had helping him what quickly became an efficient team.

Events started about a two-day march to the north, in what is today the border along North Carolina. Groups of men loyal to the King moved toward the magnet that was Augusta, Georgia. In the first few days of February, 1779 one of several militia musters took place at Poor’s Ford in Tryon County, North Carolina. William Battle, who was less than enthusiastic about the coming together of his militia company, stated soon afterwards that had he known this muster was for the purpose of going to Georgia, “no amount of persuasion should have induced him to come.” Some of the men in his company, a few without guns and many with little gunpowder, talked among themselves about turning back but were told “that those who left that company would be punished with great severity,”[4] their homes burned and stored crops taken.

Soon after setting out, Battle’s company met up, on February 5, with a larger Loyalist force under the command of Col. John Moore. As Moore’s command, now numbering between 150 and 200 men, continued moving toward the Spartanburg area, some around Battle appeared “most cast down and dissatisfied,” unhappy “with what they were doing.”[5] What they were doing is moving into the Spartanburg area, now almost empty of militia-age men who, like Battle’s company, were being pulled toward Augusta. This was a miserable time for everyone, Tory and Whig alike. The weather was cold and wet, the marching was step by weary step through deep mud. Taking care of horses and men was never ending “through a country so barren that not a berry was to be found, nor a bud to be seen.”[6] The sun, for eight days straight, never shined, and the rain never stopped, often becoming a downpour. “This I can well remember,” said Battle, “all that time the shirt on my back was not dry …”[7]

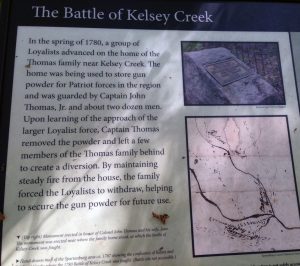

A few days earlier a similar call for help had also gone out to the Whigs. Men in both the Patriot 1st Spartan and 2nd Spartan Regiments, formed from the Fair Forest and present Union County, had already left to join with Gen. Andrew Williamson to “assist that state [Georgia] against the English who had got possession of Savannah …”[8] The result was a thin Patriot militia reserve, about twenty-five men, purposely left to guard a precious-as-gold supply of gunpowder stored at the home of Col. John Thomas, Sr.

Four years earlier, in July 1775, thirteen thousand pounds of gunpowder had been seized by Carolinians and Georgia “liberty boys” from a British merchant ship, the Phillipa, off Bloody Point, near Tybee Island.[9] It would be difficult to overestimate the importance of this gunpowder. So precious was each grain that casks were often “loaned,” to be returned or replaced, if not used immediately. George Washington, shocked and desperate at Boston, upon learning that the men in his army had only an average of nine cartridges each, managed to get about five thousand pounds sent north. Equally desperate, nearly half of the Whigs along the South Carolina coast, around Charleston and Beauford, did not have enough gunpowder in their horns to fire one shot. Another five thousand pounds went to them. Georgia, desperate to close the backdoor leading up the Savannah River, finally ended up with four thousand pounds.[10] At his Fair Forest Plantation, Colonel Thomas was sent half a ton — 1080 pounds – by South Carolina Gov. John Rutledge to safe keep and, apparently, use at his discretion. Such was the confidence and trust in the Thomas family, in a time when loyalties shifted back and forth between King and rebellion. Josiah Culbertson would state many years later that Rutledge wanted Thomas to have this powder “… to keep the Tories in awe.” These local Tories, according to Culbertson, were numerous and doing “more mischief than even the British.”[11]

At some point during the march to Augusta, probably in the late afternoon of February 6, 1779, Col. John Moore decided to send two parties ahead of his main force. One party was to capture William Wofford, a lieutenant colonel in Thomas’s 1st Spartan Regiment. The second party was to take Col. John Thomas, Sr and his supply of gunpowder. Regardless of how the raid was planned, either from orders sent to Moore by someone like Col. Boyd of Kettle Creek fame or designed by Moore himself, it was based on sound understanding of what must be done to subdue the backcountry: remove the influence of leading Rebel leaders and, at the same time, take away the means of fighting the revolution, gunpowder. This was most assuredly the only time Colonel Moore attempted to do something that would have met the approval of British Gen. Charles, Earl Cornwallis. Unfortunately the plan failed, mainly because of one man, three women, and a twelve-year-old boy.

Col. John Moore was a “weak,” “silly,” unlucky, strange, “imprudent,” “sanguine” man who acted without “caution,” “disobeys direct orders,” and seemingly appeared and disappeared at will like a jack-in-the box. He abused the British code of honor, violating a flag of truce, and did not hesitate to throw a subordinate fellow officer under the bus to save his own skin. He tended to evade the truth if not favorable to him. Men under his command complained of “much of ill management” and viewed his decisions as rather “strange business.” He was overly fond of whiskey at moments when he should have been most alert. He was someone Cornwallis would have liked to hang if it had not been “impolitic” to do so.[12] He seemed to lack a certain soldierly spirit (without more evidence, it would be too much to say courage), always appearing to be among the first to “narrowly escape” when things started to go badly, as they did at Kettle Creek, Ramsour’s Mill and King’s Mountain.[13] His error this night was being overly optimistic; failing to recognize what a fortress the Thomas home was. He can be excused for not knowing what would be found behind the thick log walls.

In contrast, Moore’s counterpart, Colonel Thomas, Sr., was esteemed by the pre-revolutionary British to the point that he was a commander of their militia, a magistrate and a justice of the peace. In 1770, he resigned his British military commission to become the sturdiest of Patriots. Important to our understanding of Thomas’s role in the backcountry is the tiny obscure fact there is no indication he meant to relinquish his duties as a magistrate and justice of the peace. Perhaps resigning his commission carried with it the implied loss of these additional duties, but Thomas continued to perform his civil duties.[14] As a military leader, this made him a most important target for the British, who wanted no one but King’s men conducting marriage ceremonies and other civil tasks.[15]

Thomas, a man of faultless loyalty, was trusted completely by southern Revolutionary architects, such as Gov. Edward Rutledge, William Henry Drayton and Gen. Richard Richardson. More telling, men in his various commands had respect, fondness and high regard for him. He was both a founder of that iron bastion of patriotism, the Fair Forest Presbyterian Church, and the original Patriot Spartan Regiment, which he commanded. He was intelligent, distinguished in appearance, and industrious, a veteran of unknown Indian conflicts, the French and Indian War, Snow Campaign, and Ring Fight. But there was something about Thomas that begs explanation. All accounts describe him, at this point in life, as elderly, seemingly tired or perhaps sick, not engaged in his command with the same spirit he once had.

Lyman Draper, maker of heroes, considered Thomas’s son-in-law Josiah Culbertson “the hero of Spartanburg.”[16] If so, he does not fit the mold from which heroes are cast. He lacked the conventional heroic attribute of noble and principled behavior. Josiah Culbertson was a hater, killer and brutal man. Culbertson could not tolerate a Tory … spared no age nor sex … on one occasion, encountered one … alone, snatched and threw away his gun from him, declaring he would not condescend to shoot so mean a creature as he was, and brained him with a club.”[17] Culbertson, a strong big man, was deadly with a knife, stabbing to death, on another occasion, one more hated Tory. If ever such hate can have a reason, Culbertson had one. A few years after the skirmish at the Thomas house, a nasty piece of work known as “Plundering” Sam Brown became enraged at not finding a sick Culbertson at the “home of a friend” (probably this same Thomas house). Young Andrew, now six, ran and hide behind Martha, his mother. Brown hacked repeatedly with his sword at the child, who “held up his hands to protect his head from the blows, but his arms were so cut up, that large particles of bone were found in his shirt sleeves …”[18] Culbertson tracked down Brown and, at a distance of two hundred yards, shot him squarely in the back, as Brown stretched upon waking.

On the night in February 1779 in the moments before Moore’s attack party arrived, there was something of an inconsistency about Colonel Thomas’s behavior.[19] He appears to have left his family to fend for themselves, while his Culbertson stayed behind. Colonel Thomas, after “concluding that a defense could not long be successfully maintained against such odds and … Dreading captivity at his advance period of life deemed it best to retire, and the guard strongly urged him to do so.”[20] This statement by Lyman Draper does not agree in detail with what Josiah Culbertson, Draper’s source for why Col. Thomas retreated, actually said: “the guard, being fearful of such odds, retreated although strongly remonstrated with by this deponent [Culbertson] leaving no one to defend the house but deponent and his mother-in-law, Mrs. Thomas.” [21] A clue as to what may have happened is found in the pension application of Matthew Patton, who provided the best account of what took place that night.

In the month of February 1779 the Whigs were informed that a body of Tories had been raised in North Carolina in the counties of Surry, Burke and Rutherford. Col. Thomas hearing this and under expectation that his house would be attacked by them sent word to this deponent [Patton] by a young lady, his daughter, Letty Thomas who came four miles in the night to give the information and that he and his aged father with what few they could collect went immediately to the aid [of] Thomas; in a few minutes after they arrived there it was announced that the Tories were approaching. They were hailed but would not answer and immediately fired and killed one of Col. Thomas’ Negroes. And that while Samuel Clouney [Clowney] and this deponent [Matthew Patton] were engaged in the house running bullets the most of their company, he believes all but one Isaiah [sic: Josiah] Culbertson, fled from the house. Mrs. Thomas then came running in and urged them also to fly for their lives as the Tories were near the house. [22]

William Shaw, who was part of the twenty-five man gunpowder guard, never mentioned any retreat by Colonel Thomas, only saying, “I was in four several engagements. The first was at the house of John Thomas in Union District, where a small party of us were attacked by an overwhelming force of Tories commanded by one Captain Pat Moore”[23] (actually Col. John Moore). This is not to suggest Colonel Thomas did not make such a retreat, separating himself from his family; rather it seems not to have been that important to most of the powder guard who were around Thomas. The reason it was remembered so well by Culbertson is, despite what he omitted in his pension application, he and his mother-in-law were not the only ones in the Thomas house. Also present were Jane Thomas’s youngest son, twelve year old William, her daughter and wife of Culbertson, Martha, and Culbertson’s mother (never mentioned by anyone, but likely also there, was Andrew, the four year old son of Josiah and Martha Culbertson).

When Colonel Thomas learned of the impending attack he immediately sent his daughter, Letitha for help, went outside, not even taking time to put on his sword or carry his gun, and directed a few men of the guard to remove the gunpowder to Rich Hill, a nearby place on Thomas’s property honeycombed with gullies, crevices and caves. A part of the guard, probably numbering about four or five if similar incidents can be used as an indicator,[24] took on this task, thinning the ranks of the defenders even more; they would not have had time to return to the Thomas house after hiding the powder in “the crevices of the Rich Hill.”[25] Also outside with her husband was Jane Thomas, probably assisting in getting horses and slaves to safety, where they would not become plunder. At some point, about the time Moore’s advance party was near enough for the first shots to be fired, Jane Thomas realized none of her family was outside and leaving with Colonel Thomas and the guard. Patton stated that “Mrs. Thomas then came running in and urged them also to fly for their lives.” Culbertson, who had a wife, mother and son to protect, refused to leave. Jane Thomas made a mother’s decision and chose to remain, or perhaps by this time it was no longer possible to get out of the house. All this may have been unknown to Colonel Thomas, who had started moving away, in the dark, with the rest of the guard. Colonel Thomas probably did not deliberately leave behind his family, but was simply is unaware, until it was too late to do anything, that they were not part of the retreat.

What now took place was no longer about protecting gunpowder. It was about protecting family. Matthew Patton and his good friend, Samuel Clowney were the last of the powder guard to leave the house. They had been downstairs, near the fireplace, running bullets – melting lead and molding the liquid into musket balls. They almost waited too long to get out. When they did, they were confronted by several of Moore’s advance party. “They took up their guns and cocked and presented them threatening to shoot and returning or retreating of the same, and by the use of some address they both made their escape when Isaiah [sic: Josiah] Culbertson whom they had left upstairs in the house commenced firing on the Tories whom he supposed to have been about two hundred in number.”[26] We will never know what was said in this “address,” when both sides leveled muskets but did not fire. Clowney was known for his quick thinking and glib tongue. Perhaps some of the Tories knew the two men, having served with them previously. This standoff gave time to talk. Whatever the case, there was certainly a reluctance on the part of the Tories to shoot down these two particular men.

What now took place was no longer about protecting gunpowder. It was about protecting family. Matthew Patton and his good friend, Samuel Clowney were the last of the powder guard to leave the house. They had been downstairs, near the fireplace, running bullets – melting lead and molding the liquid into musket balls. They almost waited too long to get out. When they did, they were confronted by several of Moore’s advance party. “They took up their guns and cocked and presented them threatening to shoot and returning or retreating of the same, and by the use of some address they both made their escape when Isaiah [sic: Josiah] Culbertson whom they had left upstairs in the house commenced firing on the Tories whom he supposed to have been about two hundred in number.”[26] We will never know what was said in this “address,” when both sides leveled muskets but did not fire. Clowney was known for his quick thinking and glib tongue. Perhaps some of the Tories knew the two men, having served with them previously. This standoff gave time to talk. Whatever the case, there was certainly a reluctance on the part of the Tories to shoot down these two particular men.

This reluctance was not general; moments earlier, the only known casualty of the skirmish occurred. Colonel Thomas seems to have stationed a slave, a “capital” fellow and “the only slave [he] could place confidence in” somewhere on one of the paths leading to the house. It was this slave’s responsibility to “hail” whoever came up, to determine if they were part of the raiding party or one of the powder guard coming in. When the Tory raiding party was asked to identify itself, this “most valuable” man “on whom he [Thomas] principally depended for the conducting of his whole plantation business” was shot.[27] Perhaps the attackers were told by Patton and Clowney that the gunpowder was no longer in the house and, because there was no longer a need to fight, and being former comrades, they were allowed to escape.

After Patton and Clowney left, defense of the Tomas house in the face of Colonel Moore’s attackers was left to a frontier sharpshooter assisted by three women and a young boy. Most accounts state that the attacking Loyalist party was made up of about 150 men, but this was probably the total number under Moore’s command, with a much smaller party going to the Thomas House, part of a mounted militia company. Facing them, the five-member sniper team of Culbertson and his family, posted at upstairs windows, worked so well that the Loyalists thought “some eight or ten persons at least were concealed in the house.”[28]

No one who wrote of this remarkable defense described in detail how the five defenders worked together. Did the women and child load muskets so the sharpshooting Culbertson could sustain a rapid fire, or did the women do some of the shooting? One writer said that Jane Thomas’s was “running bullets,” a term that generally meant casting musket balls from molten lead,[29] implying that she was downstairs at the fire while the others were upstairs sniping at attackers. “Running bullets” or “running ball” could also refer to carrying ammunition from a storage location to the shooters, or to loading guns with loose powder and ball instead of prepared cartridges. Regardless of these details, it is clear that five family members worked together efficiently enough to intimidate their assailants, inflicting casualties and preventing the house from being stormed; “every shot proved effectual.”[30] At least four or five of the raiding party were wounded.

In the mythology growing out of this night, it became told that this little team drove off Moore’s 150 men. Perhaps this happened to the much smaller raiding party, after the leader was wounded. Moore’s men did break off the siege and quickly left the area, albeit probably not so much because of the staunch defense of the house as because they knew that help for the defenders was on the way. A Whig militia man named William Goodlett’s recalled in his pension application that “during this time he was called upon to pursue a Tory Colonel Moore who came from North Carolina and was marching to Georgia. The company with which this applicant was then serving pursued this Colonel Moore from Abbeville but were unable to overtake him or his troops.”[31]

Jane Thomas was a woman of piety, lively with a good personality. She loved buttermilk, but would not drink tea out of respect for those who died in the war, among which were two of her sons. Contrary to what British Maj. George Hanger[32] wrote, stating that this was a country where not an angel could be found, Mrs. Thomas was known for her beauty; a petite woman with “brown eyes and hair, rounded and pleasing features, fair complexion.” Her four daughters were no less attractive, being of “the same loveliness of character and beauty of person, which they inherited from their mother.” Martha Culbertson was “a woman of great beauty.”[33] One wonders what Major Hanger would have thought if he could have seen these three Thomas women on this night, with their hands, mouths and faces blackened from gunpowder, sweaty, hair awry, smelling of sulphur.

[1] John Belton O’Neall Landrum, Colonial and revolutionary history of upper South Carolina (Greenville, SC: Shannon & Co., 1897), 2

[2] Ibid.

[3] Katherine Cann, Turning Point: The American Revolution in the Spartan District (Spartanburg, SC: Hub City Press), 18.

[4] Lyman Draper “Joseph Cartwright Deposition, Sept. 1, 1779” (Birmingham, AL:Draper Manuscript Collection, 3VV), 250-251.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Edward McCrady, The history of South Carolina in the revolution, 1775-1780 (New York: The Macmillan Company, 1902), 322.

[7] Ibid.

[8] “James Fergus-Revolutionary War Pension Application W25573”, http://revwarapps.org/w25573.

[9] Jon R Hufford, “Enough Gunpowder to Start a Revolution,” eScholarshipRepository, http:// esr.lib.ttu.edu/lib, 2-3, accessed July 16, 2016.

[10] Keith Krawczynski, William Henry Drayton South Carolina Revolutionary Patriot (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University, 2001), 148.

[11] “Josiah Culbertson-American Revolution Pension Application S16354,” http://revwarapps.org/S16354.

[12] Ian Saberton, ed., The Cornwallis Papers (East Sussex, England: The Naval & Military Press, 2010), 1:162,182,184,185,188,193,202,237,245,363. None of the above descriptive adjectives or phrases come from Saberton or myself. All were used by contemporaries of Moore and can be found in primary sources where Colonel Moore is mentioned. The British hated the man, with nothing but contempt for his leadership and character. It is because of Moore’s premature actions, along with one or two more, at Ramsour’s Mill, in apparent open defiance of Lord Cornwallis’s orders, that the British southern strategy started to sour.

[13] William S Powell, Dictionary of North Carolina Biography, Vol. 4 L-O (Chapel Hill, NC: 2000), 301.

[14] Theron (Joan Goar) Bratton, “Solomon Crocker’s Bible,” Family Ties Vol. 1 (Oxford, MS: Skipwith Historical and Genealogical Society, Inc. 1981). On February 14, 1780 Solomon Crocker and Susannah Catharine were married “at the house of Col. John Thomas … who performed the ceremony.”

[15] Landrum, “Colonial and revolutionary history of Upper South Carolina”, 107. “Nor were these the only powers vested in Ferguson and Hanger … the right to perform the marriage ceremony.”

[16] Robert Barton Puryear III, ed., Border Forays & Adventures — From the Manuscripts of Lyman Copeland Draper (Nashville, TN: Westview Book Publishing, 2006), 375.

[17] Puryear, Border Forays, 374.

[18] Ibid.

[19] McCrady, History of South Carolina, 608; J.D. Lewis, “Colonel John Thomas, Sr.” The American Revolution in South Carolina, www.carolana.com, accessed July 9, 2016; Irene Jones Cornwell, “Col. John Thomas,” Southern Campaigns of the American Revolution, May 2005, Vol 2 No. 5, southerncampaign.org/newsletter/v2n5.pdf, 15. Downloaded May 11, 2016.

[20] Lyman Draper “Josiah Culbertson (1748-1839)” (Birmingham, Alabama: Draper Manuscript Collection, MSS-D5), 192.

[21] Josiah Culbertson Pension Application.

[22] “Matthew Patton Revolutionary War Pension Application S18153,” http://revwarapps.org/S18153.

[23] “William Shaw Revolutionary War Pension Application R9446,” http://revwarapps.org/R9446.

[24] John C. Parker, Parker’s Guide to the Revolutionary War in South Carolina (West Conshohocken, PA: Infinity Publishing, 2013), 424. This supply of gunpowder, at least some of it, had a much storied existence. Another incident similar to the Thomas House Skirmish took place seventeen months later, about forty miles east and south of the Thomas Plantation. This time things did not end as well for the Whigs. Seven Union County men, all well known and part of the 2nd Spartan Regiment, hid the powder for a second time in the Fair Forest. They were attacked by “Bloody Bill” Cunningham. This skirmish became known as Brandon’s Defeat, after the regiment’s Colonel, Thomas Brandon. Robert Lusk, future father-in-law of Letitia Thomas, was captured and forced to reveal what happened to the powder. The Tories never found it.

[25] Draper, “Josiah Culbertson,” 191; O’Kelley, 239.

[26] Patton Revolutionary War Pension Application.

[27] Theodera A. Thompson and Rosa S. Lumpkin, ed., Journals of the House of Representatives, 1783-1784 (Columbia: SC: University of South Carolina Press, 1977), 85; William E. Wiethoff, Crafting the Overseer’s Image (Columbia, SC: University of South Carolina Press, 2006), 57.

[28] B. F. Perry, “Revolutionary Incidents,” in Figures of the Revolution in South Carolina: An Anthology (Columbia, South Carolina: Southern Studies Program, 1976), 129-30.

[29] “We have at last got in the way of running bullets … Leech have been at the Mari’s works … and says he saw him cast several, and after that Day he was in no doubts but he cd run 100 or more a day ….” Naval Documents of the American Revolution, Volume 6, August 1, 1776-Oct. 31, 1776, http://ibiblio.org/anrs/docs/E/E3/ndar_v06p01.pdf

[30] Ibid.

[31] “William Goodlett Revolutionary War Pension Application W8857” http://revWarApps.org/W8857.

[32] Lyman C Draper, King’s Mountain and Its Heroes (Cincinnati, Ohio: Peter G Thomson Publishing, 1881), 70. “In the back country you may search after an angel with as much chance of finding one as a parson.”

[33] J. B. O. Landrum, History of Spartanburg County, embracing an account of many important events, and biographical sketches (Atlanta, GA: Franklin Prtg and Pub, 1900), 188.

Recent Articles

The Home Front: Revolutionary Households, Military Occupation, and the Making of American Independence

A Strategist in Waiting: Nathanael Greene at the Catawba River, February 1, 1781

This Week on Dispatches: Brady J. Crytzer on Pope Pius VI and the American Revolution

Recent Comments

"A Strategist in Waiting:..."

Lots of general information well presented, The map used in this article...

"Ebenezer Smith Platt: An..."

Sadly, no

"Comte d’Estaing’s Georgia Land..."

The locations of the d'Estaing lands are shown in Daniel N. Crumpton's...