John Paul Jones tends to overshadow the study of the American Revolution at sea. While his accolades are well deserved, Jones earned many of them with John Peck Rathbun at his side. An American-born merchant captain who joined the Continental Navy at its beginning, Rathbun’s exploits are as daring as Jones’s, but less well known.

Rathbun was born in Exeter, Rhode Island in 1746. Orphaned at an early age, he likely grew up in Boston under the tutelage of his maternal uncle, Thomas Peck, and went to sea as a ship’s boy. By 1773, Rathbun commanded a small schooner plying the coastal routes in New England and Canada’s maritime provinces. Peck was actively participating in the patriot cause, likely involving Rathbun in Boston’s political cauldron. When the 1774 Intolerable Acts closed Boston’s port, the young cargo captain found himself beached. That winter and spring the restless skipper courted a much younger Polly Leigh, marrying her less than a month after Lexington and Concord.[1]

The outbreak of fighting led Rathbun to leave Boston and head for Rhode Island, where his last living sister resided. Conveniently, Rhode Island’s Esek Hopkins had just become Commander in Chief of the new Continental Navy, leaving recruiting in the hands of Abraham Whipple. By November, 1775 Rathbun had signed papers to join the Navy of the United Colonies and departed for Philadelphia with a handful of recruits aboard the sloop Katy, already in the service of Rhode Island under Whipple’s command as a warship defending the colony’s interests.[2] Katy also bore John Trevett to Philadelphia as a new recruit in the Marines.[3] Arriving in Philadelphia, the Rhode Island sloop joined the Continental Navy as well, becoming Providence. Rathbun would enjoy a fruitful relationship with both the ship and the Marine.

During the winter of 1775-1776, Congress and its agents assembled a small squadron by buying and converting civilian ships and placing them under Hopkins’ command. By February 1776, the Alfred, Columbus, Cabot, Andrew Doria, Fly, Hornet, Wasp, and Providence swung at anchor in the mouth of the Delaware Bay. Collectively they mounted just 114 guns, most of which were relatively small, 200 Marines, and 700 sailors and officers, the newly commissioned second lieutenant John Peck Rathbun among them aboard the Providence.[4]

Congress set Hopkins’ eyes south, wishing his squadron to put a stop to water-borne raids in Virginia and the Carolinas.[5] Hopkins had other ideas. He led his little fleet toward the Bahamas in search of arms and ammunition. Only six ships, including Providence, arrived on March 1. [6] It was Rathburn’s first cruise as a naval officer.

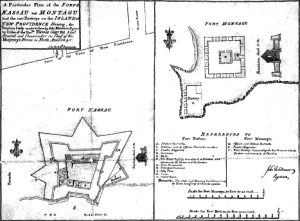

Hopkins hoped to surprise the British governor of the Bahamas, but word of his squadron’s departure arrived in the islands ahead of him. Two dilapidated forts guarded the island’s largest town, New Providence. Hopkins’ initial attempt to seize Fort Nassau by sneaking Providence, two captured schooners, and a landing party into the harbor failed when his largest warships hove into sight before Providence could reach its target. The Continentals eventually landed some Marines and sailors east of town, from where they marched overland. The local militia garrisoning Forts Montagu and Nassau quickly abandoned them, leaving the Marines in control of the town and harbor. Hopkins occupied New Providence for two weeks to remove as much war materiel as he could, going so far as to charter a local ship to carry some of it back to the colonies.[7]

Because Hopkins’ early plans relied so heavily on the Providence, Rathbun likely would have worked with the Marine contingent and reacquainted himself with Lt. John Trevett, who was assigned to the Columbus but was also a member of the landing party.

When Hopkins departed, he set sail for Rhode Island. A minor clash on the return tarnished the entire raid. After taking a few prizes off New England’s coast, the fleet encountered HMS Glasgow, a 20-gun frigate. Though outnumbered, Glasgow out-sailed and out-fought the American squadron, retiring successfully after inflicting severe damage.[8] Providence proved the greatest disappointment. Though she was among the fastest ships in the fleet, Capt. John Hazard failed to engage Glasgow. Hazard was court-martialed and replaced with John Paul Jones in his first independent naval command.[9] Rathbun initially remained the second lieutenant, but eventually rose to first lieutenant, becoming Jones’s executive officer.

Jones and Rathbun spent May to October of 1776 aboard Providence cruising familiar waters, convoying civilian ships and looking for British prizes. Jones biographer Evan Thomas argued that the two established a close working relationship. Jones was a foreign-born disciplinarian only recently arrived in the colonies. Rathbun, on the other hand, was a successful America-born merchant skipper who knew the waters Providence plied quite well. He seems also to have been more familiar with Providence as a ship type. Rigged as a single-masted sloop, she touted a vast amount of canvas for her size, making her fast and maneuverable, but tricky to handle.[10] Having served on the ship longer, Rathbun may also have enjoyed a better relationship with the crew than the prickly Jones.

As the British invasion of New York got underway that summer, Rathbun found himself anchored with Jones in the Delaware Bay while the captain sought better orders. The Marine Committee eventually provided them, and Providence left Delaware for a prize cruise on August 21.[11] Armed with just twelve four-pounders and a seventy man crew, Jones and Rathbun set off. Not content with simply taking prizes and the wealth they promised, Jones struck targets on land and in port, including the harbor of Canso in Nova Scotia and two ports on the Island of Madame.[12] Jones also tempted fate twice, separately encountering the British frigates Soleday and Milford. In both instances, he out-sailed the much better-armed warships, seemingly taunting their captains by cutting across their paths or alternatively shortening sail to bring them in close before adding sail to pull away.[13]

Following his return to the colonies in October, Jones was promoted to command the Alfred. Rathbun went with him as first lieutenant. Clearly, both men valued their partnership. Jones’s first assignment was to rescue American prisoners in Nova Scotia, but manpower shortages delayed his departure. While waiting, Jones presided over a court martial, Rathbun joining as a member of the court.[14] Finally Alfred, still short of men, started its mission with Providence. Within a day, Jones came across the American privateer Eagle, out of Providence, Rhode Island. Because privateering offered greater chance for financial reward than the Continental Navy, it was a popular destination for deserters. Consequently, Jones decided to board Eagle and search its crew to meet his own needs. He sent two boats across, Rathbun commanding one from Alfred and marine Lt. John Trevett aboard one from Providence.[15]

Rathbun commandeered Eagle and brought her under Alfred’s stern to expedite his search. The next morning Rathbun re-boarded the privateer and began his search. The privateer’s prize master complained of his crew’s treatment at Rathbun’s hands. According to the him, Eagle’s captain acceded to Jones’s order to remove any suspect crewmen, but Rathbun indicated that he planned to take all the men on board and removed twenty-four crewmen “by Force and Violence.” Rathbun also ordered a search of the hold at sword point. Finding more men, Rathbun then heaved Eagle’s first lieutenant on deck and committed “many other Acts of high insult.”[16]

Foul weather ended Jones’s rescue plans and sickened his crews. From time to time he still took prizes, typically supply ships supporting British forces in Canada. The normal procedure called for placing prize crews aboard and dispatching the ships to an American port, but one such ship, John, was an armed sloop. Jones placed Rathbun in command and ordered him to keep station with Alfred.[17] Rathbun’s brief period in command hints at a charitable streak that the prickly Jones may have lacked. Jones sent word by a Marine lieutenant that John’s master, Edward Watkins, had fomented some sort of unrest. Rathbun investigated and determined the reverse, that Watkins had sought to tamp it down, going so far as to take a cutlass from one rebellious crewman. He asked Jones for a personal favor, to let Watkins remain aboard John for the time being as Watkins was ill. One suspects he may also have sought to shield Watkins from Jones’s wrath.[18]

Alfred returned to Boston in December, where authorities sought to arrest Jones over the Eagle affair. Involved in suits and counter-suits, he lost Alfred and was only offered an opportunity to return to the Providence. Jones and Rathbun were both dissatisfied with the state of affairs and decided to make their cases directly to the Marine Committee. Rathbun detoured to see Esek Hopkins in Rhode Island on the way. There, he secured a letter of recommendation from Hopkins, addressed to William Ellery, a member of the Committee. Hopkins praised Rathbun, explaining:

he [Rathbun] has Served since the Fleet went from Philadelphia there being no Vacancy whereby I could promote him agreeable to his Merits—if there Should be any Vacancy with you I can recommend him as a man of Courage and I believe Conduct, and a man that is a Friend to his Country—and I believe the most of the Success Capt [John Paul] Jones has had is owing to his Valour and good Conduct, he likewise of a good Family in Boston—Any Service you may do him will be Serving the Cause—he able to give you some Account of Captn Jones’s Conduct which you may give Credit to—[19]

Hopkins graciously allowed Rathbun to give a copy to John Hancock, president of the Committee.

While Rathbun was lobbying Hopkins and Hancock, the Eagle affair continued to plague Jones. By the end of April, Rathbun was given command of Providence and was on his way to Rhode Island to assume his new post.[20] To Rathbun’s disappointment, Hopkins had already sent Providence on a cruise, which ended in June. Rathbun finally rendezvoused with his ship in Bedford, Massachusetts early that summer. His new captain of Marines was John Trevett.[21]

After completing repairs to Providence, Rathbun returned to sea, skirting past British-occupied New York. He quickly demonstrated a dash of Jones’s aggressiveness. Spying a squadron of five ships convoying south off Sandy Hook, New Jersey, Rathbun mirrored their course from inshore, eventually attacking the largest, which proved to be a 16-gun ship, Mary. Mary and two of the vessels fought him off, but Rathbun still managed to capture a small schooner.[22] Unfortunately, the fight with Mary cost Rathbun his sailing master. The next day, Providence continued south, searching for Mary, but instead encountered a British privateer. The privateer’s captain thought better of engaging Providence and managed to evade her. By August, Rathbun had returned, disappointed, to Bedford.

Rathbun’s second cruise in command of Providence took him south. Departing Bedford in mid-November, he arrived near Charlestown (Charleston) in December and promptly captured a Loyalist privateer, the Governour Tonyn.[23] Rathbun took that ship into Georgetown, South Carolina, disembarked, and retired with Trevett and his prisoners to Charleston. There, Rathbun heard that Mary was in the port of New Providence for repairs and resolved to pay her, and the town, another visit.

He also encountered Capt. Nicholas Biddle, commanding the frigate Randolph. Biddle, well-acquainted with Trevett, pressed the Marine to join his crew, but Trevett informed him that he had already committed to sail for New Providence under Rathbun. Mary loomed too large for Trevett to abandon his promise.

As Providence returned to sea in January, 1778 bound for the Bahamas, Rathbun and Trevett marked the beginning of their third year of war. The Marine took a moment to contemplate the risks of raiding Nassau with a single ship, writing “I have had A Long time to think of What I am A Going to undertake but I am Very Well Satisfied that we Are in a Good Cause & we are fiting the Lords Battel.”[24] Providence encountered three British vessels at first light the day after leaving Georgetown. They chased her and Rathbun could not shake them, despite tossing supplies overboard to lighten the ship. Fortunately, Providence stayed just far enough ahead to lose its pursuers that night by dousing its lights and dropping sail. Once the British passed by, Rathbun raised sail and altered course. His horizons were clear the next morning.

With fewer provisions, Rathbun made straight for New Providence. The Continental captain opted to give Hopkins’ initial plan for sneaking into New Providence another try. After arriving offshore, he shipped the top sail mast and yard, housed the guns, and sent most of his men below to disguise Providence as a simple merchant vessel. Around midnight on January 27, Providence came abreast of the harbor under a light breeze while Trevett prepared his team of twenty-eight raiders below decks. No one in Nassau raised the alarm. In the distance, anchored near the wall of Fort Nassau, Mary beckoned.[25]

With Providence hanging off the harbor, Trevett loaded his men into a barge and took them ashore in two trips, landing a mile from Fort Nassau. They carried a scaling ladder, their weapons and ammunition, but no food or water. Drawing on his experience in the 1776 raid, Trevett went forward, discovered the fort lacked a picket, and entered alone through an embrasure. He hid and measured the march of two sentries. As the cry “all is well” from opposite corners of the fort died on the breeze, he slipped back out and brought his men forward with their scaling ladder. They waited below the walls another thirty minutes until “all is well” carried over the wall again, then raised the ladder. Everyone followed Trevett back into the fort. Trevett ordered his men not to fire lest it alert the town. Just as the Marine captain turned a near corner around the barracks, he ran smack into one of the sentries and seized the initiative by grabbing the man’s collar and forcing him into the nearest door. While the confused sentry stammered out his innocence of any transgression—“for God Sak What have I done”—the next man behind Trevett fired his pistol at the guard. He missed. Fortunately, the sound did not provoke a reaction. Trevett and his men quickly captured the other sentry. In the process, he discovered several of the fort’s eighteen-pounders were loaded and lit matches were nearby. They were ready to signal the local militia, as the captured sentries informed him that 500 men would assemble to defend the fort ten minutes after a cannon discharge. Trevett opted to maintain appearances by putting out his own sentries and keeping up the cry “all is well,” which was echoed from a ship in the harbor. Rathbun’s landing force spent the rest of the night arming the cannon and training them down the streets of New Providence and at ships in the harbor.[26] Meanwhile, a nasty gale that blew all night forced Rathbun to weigh anchor and put out to sea.[27]

Dawn found a striped American flag flying over Fort Nassau. Trevett’s first move in the morning was to send a note to a local merchant and American expatriate, James Gould, who arrived and climbed the ladder into Fort Nassau for a quick meeting. There, the Marine informed him that a landing party of 200 men and thirty officers came from Captain Biddle’s squadron and was bound for Jamaica, would not molest civilian property, except war materiel, and would take the Mary as a prize. He further told Gould that he had provisions for all his men, but demanded breakfast just the same. Gould agreed and while Trevett waited for his morning meal, he sent a three-man detail through the town to the gates of Fort Montagu. They demanded, and received, the surrender of that fort as well.[28]

That task accomplished, Trevett next set his eyes on Mary, which lay within a pistol’s shot of Fort Nassau. The captain was ashore ill and the executive officer initially declined to allow Trevett’s party to board the vessel, but after some harsh and direct language, which no doubt included reference to the shore-based cannon trained on her, Trevett took possession of the ship. Finally, with the town in confusion, Trevett and his men sat down to a hearty breakfast, going so far as to request, and get, cooked turtle for dinner.[29]

That afternoon, Providence hove into sight, a British privateer of sixteen guns, Gayton, just two hours behind her. Trevett and Rathbun decided to haul down the American colors and maintain the ruse that all was well in New Providence. The trick failed as townsmen and women had already taken to the hills and were signaling alarm. Gayton passed back outside the bar, at which point Fort Nassau loosed three eighteen-pound rounds at her. The Continentals hit her in the main beam, but did not significantly damage her and she came to anchor within sight, but outside the range, of Fort Montagu. Trevett ordered his detail at Fort Montagu to spike the guns, break the rammers, and ruin the powder before abandoning the fort and returning to Fort Nassau. All in a day’s work for one of the country’s first Marines.[30] With Fort Montagu abandoned, Gayton moved deeper into the harbor, closer to Providence. Rathbun moored her abreast of the town and set her on her springs, which enabled the ship to pivot while anchored and expanded her field of fire. He resisted going ashore lest Gayton attack.[31]

January 28 dawned clear and pleasant. While Rathburn and his sailors set to work readying Mary for sea, Trevett and his party remained in Fort Nassau. Their force was too small to occupy New Providence and Trevett observed large numbers of armed men moving about the town and hills above the fort, making his Marines and accompanying sailors nervous. The island’s governor and customs house collector approached the fort to ask about Trevett’s intentions. He repeated the story he had told Gould: under Commodore Biddle’s orders, they were to seize the fort, all armed vessels, and all American property they could find, while leaving civilian property undisturbed. Trevett later went into town in search of equipment from Mary around its captain’s house, which he found and directed be delivered to Providence and Mary.[32]

Rathbun came ashore on the 30th and visited Trevett in the fort. He planned to depart the next day and required three pilots, one for Providence, one for Mary, and a third for a sloop. He also planned to take two schooners then in the harbor. Trevett proposed another ruse to get the required pilots, which Rathbun approved. Later in the day, someone Rathbun knew informed him that the locals planned to attack in company with men from Gayton’s crew. Trevett did his best to keep up his bluff and disguise the Americans’ imminent departure, inviting them to do so at dawn. As the night wore on, he and his landing party set about wrecking the fort and its guns.

Daylight on the 31st found Providence with her mainsail up and Trevett ready to go. His Marines towed the scaling ladder into the harbor before letting it drift and heading for Providence. When she finally passed the bar, her gaggle of charges included Mary, a brig, two schooners, and thirty Americans who had been held prisoner in New Providence.[33] The next day, Rathbun and Trevett parted company as the Marine boarded Mary to travel home. The two ships were separated when a British ship came upon Providence and its prize vessels, with Mary eventually making her way to New England.[34] After a passage troubled by inclement weather, she arrived at Bedford and a rendezvous with Providence. Rathbun left for home and directed Trevett to handle legal matters regarding Mary’s disposition and his crew’s prize money.

Rathbun captained the Providence on two more successful cruises before taking command of the 28-gun Queen of France in 1779. There, in July, his ship was sailing in heavy fog as part of a three-ship squadron and stumbled into the midst of a large British convoy escorted by a ship of the line and several frigates. Rather than doing the prudent thing and slinking away, Rathbun impersonated a British captain and tricked four merchantmen into surrendering to his boarding parties, again displaying the audacity he had demonstrated aboard Providence. Between them, the other two Continental ships captured six more prizes. It was, perhaps, the Continental Navy’s richest haul during the entire war.[35] 1780 found Rathbun and the Navy part of Charleston’s defenses and he was captured when that city fell to British forces. Paroled, Rathbun bought the Kingston Inn in Little Rest, Rhode Island and settled down. Businessmen in the privateering business soon approached him to take command of the 34-gun brigantine Wexford and in August 1781, Rathbun went back to sea, bound for the British Isles. Damaged in a storm while crossing the Atlantic, Wexford encountered a swifter and more heavily-armed British frigate off the southern coast of Ireland. After a chase and desultory few rounds from his guns, Rathbun accepted the inevitable and hauled down his colors. He spent the rest of the war shuttling among English prisons before dying of illness in Old Mill Prison outside Plymouth in June, 1782.[36]

Rathbun left behind no great quotes or sea fights and his death during the Revolution precluded service under the flag of the United States. He did not go on to serve in the Quasi-War with France, the conflict with the Barbary Pirates, or the War of 1812, many of whose heroes began their naval careers in the Revolution. Yet, his audacity and aggressiveness easily match those of John Paul Jones, Nicholas Biddle, John Barry, or Gustavus Conyngham. Bloodlessly capturing New Providence and carrying away several prizes with nothing more than a small, lightly-armed sloop and James Trevett’s bluffing skills is the stuff of legend.

[1] “Merchant Skipper Becomes Officer in Continental Navy,” Rathbun-Rathbone-Rathburne Family Historian, Vol. 2, No. 4, October 1982, 52. Rathbun’s last name is spelled several ways in various documents: Rathbun, Rathburn, Rathbourne, Rathburne, etc. The twentieth-century Navy named two ships after Rathbun, and misspelled his name each time.

[2] “Providence I (Slp),” Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships (Washington, DC: Naval History and Heritage Command), Available at: http://www.history.navy.mil/research/histories/ship-histories/danfs/p/providence-i.html, accessed May 26, 2016.

[3] “Journal of John Trevett,” December 3, in William Bell Clark, ed., Naval Documents of the American Revolution, American Theatre: Sept. 3-Oct. 31, 1775, European Theatre: Aug. 11, 1775-Oct. 31, 1775, American Theatre: Nov. 1, 1775-Dec. 7, 1775, Volume 2 (Washington, DC: The U.S. Navy Department, 1966), 1255. The Navy Department has continuously assembled and published Naval Documents of the American Revolution, hereafter NDAR, since 1964. Future cites will refer to NDAR by year of publication, volume, and page.

[4] James M. Volo, Blue Water Patriots: The American Revolution Afloat (Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc., 2006), 105-106.

[5]“Journal of the Continental Congress,” December 2, 1775 in NDAR, 1966, 2:1231-1232. The Naval Committee’s order to Hopkins is contained in NDAR, 1968, 3:637-638.

[6] Nathan Miller, Sea of Glory: A Naval History of the American Revolution (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, rev. ed., 1992), 107.

[7] Robert L. Tonsetic, Special Operations in the American Revolution (Philadelphia: Casemate, 2013), 52-63; See also Tim McGrath, Give Me a Fast Ship: The Continental Navy and America’s Revolution at Sea (New York: NAL Caliber/The Penguin Group, 2014), 52-56.

[8] Miller, Sea of Glory, 112-115.

[9] Volo, Blue Water Patriots, 107-109.

[10] Evan Thomas, John Paul Jones: Sailor, Hero, Father of the American Navy (New York: Simon and Schuster, 2003), 56-57.

[11] “Narrative of Captain John Paul Jones, August 21 to October 7,” NDAR, 1972, 6:1148-1149.

[12] Ibid., 1149. See also “Diary of Simeon Perkins, Liverpool, Nova Scotia, Friday, Oct. 11th,” NDAR, 1972, 6:1211-1212.

[13] Samuel Eliot Morison, John Paul Jones (New York: Time Incorporated, 1964 ed.), 61-62; Thomas, John Paul Jones, 59-61, 64-65.

[14] “Court Martial of James Bryant, Gunner of the Continental Brig Hampden, October 23, 1776,” NDAR, 1972, 6:1378-1380. Bryant was found guilty of mutiny, but only cashiered from the service.

[15] “Captain John Paul Jones to Commodore Esek Hopkins, extract, 2nd November 1776,” NDAR, 1976, 7:16-17.

[16] “Deposition of Justin Jacobs,” attached to Jones’ report to Commodore Hopkins, extract, 2nd November 1776, NDAR, 1976, 7:16.

[17] “Captain John Paul Jones to Lieutenant John Peck Rathbun, Novr 25th, 1776,” NDAR, 1976, 7:270-271.

[18] Lieutenant John Peck Rathbun to Captain John Paul Jones, Novr 25,” NDAR, 1976, 7:71.

[19] “Commodore Esek Hopkins to William Ellery, Providence March 13 1777,” NDAR, 1980, 8:99-100. Errors in the original.

[20] “Merchant Skipper Becomes Officer in Continental Navy,” 55.

[21] “A Muster Roll of All Officers Seamen & Marines Belonging to the Continental Armed Sloop Providence Commanded By John Peck Rathbun ESQR From June 19, 1777 to [August 28, 1777]” NDAR, 1986, 9:830. Trevett had also sailed aboard Providence on her cruise prior to Rathbun’s arrival.

[22] “John Peck Rathbun Takes Sloop Providence to Sea,” Rathbun-Rathbone-Rathburn Family Historian, Vol. 2, No. 1, January 1983, 4-5; See also, “Providence Gazette,” August 16, 1777, NDAR, 1986, 9:753; “New York Gazette,” August 18, 1777, NDAR, 1986, 9:765-766; Journal of Marine Lieutenant John Trevett, Continental Navy Sloop Providence, August 31, NDAR, 1986, 9:853-854.

[23] “The South Carolina and American General Gazette, December 25, 1777,” NDAR, 1996, 10:809. The Governour Tonyn carried several African American fisherman who turned out to be slaves. Rathbun planned to return them to their owners. “Journal of Marine Captain John Trevett, November-December 1777,” NDAR, 2005, 11:1169-1179.

[24] “Journal of Marine Captain John Trevett,” 1-31 January 1778, NDAR, 11:245. Errors in original.

[25] Ibid.

[26] Ibid., 245-247.

[27] Hope S. Rider, Valour Fore and Aft: Being the Adventures of the Continental Sloop Providence, 1775-1779, Former Flagship Katy of Rhode Island’s Navy, (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1977), 142-143.

[28] “Journal of Marine Captain John Trevett,” 1-31 January 1778, NDAR, 11:247.

[29] Ibid., 247.

[30] Ibid., 248.

[31] Rider, Valour Fore and Aft, 50.

[32] “Journal of Marine Captain John Trevett,” 1-31 January 1778, NDAR, 11:249.

[33] Ibid., 251. Trevett’s memory, or his writing, did not serve him well here. Several of the prisoners rescued from New Providence participated in taking the Mary and two sloops, likely the Washington and Tryal. “Memorial of Captains Cornelius Anabil, John Cockrom, Nathan Moar, and Isaac Mackey to the Continental Congress,” February 21, 1778, NDAR, 11:400. A family historian only credits Rathbun with two prizes on this raid. See “John Peck Rathbun Takes Sloop Providence to Sea,” 6-7. British accounts, however, square more closely with Trevett’s. One contemporary source credited the raid with five captures; a second with only four. See “Extract of a Letter from Rio Novo Bay, St. Mary’s, in the Island of Jamaica, Feb, 21 1778,” NDAR, 11:401 and, “Lieutenant Governor John Gambier to Lord George Germain, 25th Feb 1778,” NDAR, 11:431. The smaller vessels appear to have been prizes of the Gayton. Modern histories indicate that Rathbun burned the schooners, which might explain some of the discrepancies. Rathburn may have captured five vessels, but having burned two, could only treat three as prizes. See, for example, Rider, Valour Fore and Aft, 155; McGrath, Give Me a Fast Ship, 207-208.

[34] “Journal of Marine Captain John Trevett, 18-21 February 1778,” NDAR, 11:395-396.

[35] “Capt. Rathbun Gets Command Of 28-Gun Queen of France,” Rathbun-Rathbone-Rathburn Family Historian, Vol. 3, No. 2, April 1983, 20-21; Miller, Sea of Glory, 411-412.

[36] “Rathbun is Captured Again, Dies at 36 in English Prison,” Rathbun-Rathbone-Rathburn Family Historian, Vol. 3, No. 3, July 1983, 36-38, 46.

4 Comments

I don’t think many people are aware of New Providence having had any place in the AWI after the initial action in 1776, this is a fascinating story. Rathbun is indeed an unsung hero.

Thanks for reading the piece. When I first came across the New Providence raid (both of them, actually), I thought: “what a great movie!” Still think so.

I am a proud sailor who was aboard the USS Rathburne DE 1057, 1972-1975. Named in honor of Rathbun. I am also a historian at heart. It would be great to have a documentary about him so more people would know what a brave patriot he was.