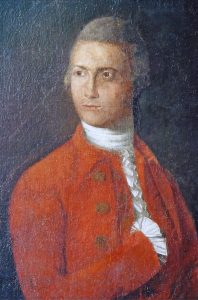

John Johnson was the only white son of the Anglo-Irish immigrant William Johnson, the superintendent of Northern Indians, who gained considerable fame, fortune and a knighthood by commanding the 1755 action at Lake George, defeating a French and Canadien expedition and capturing its commander. William gained further recognition and notoriety by assuming command of the 1758 siege of Fort Niagara, and a few days later accepting the surrender.

William’s fair dealings with the Six Nations and his genuine admiration for their society led to his acceptance into the Mohawk tribe, and his influence spread across the confederacy and its network of allied tribes. Although his common law Palatine German wife had delivered him a son and two daughters, the randy Sir William sired several mixed race children, including two sons who, following Native custom, lived with their father in their teens.

Thirteen-year-old John accompanied his father at Lake George, at Fort Niagara as a cadet, and as his military aide for Detroit’s 1761 official capitulation. John grew up in a centre of Native trading and diplomacy surrounded by warriors and sachems, and British and colonial officers. He developed a deep knowledge of Iroquois governance and customs, a fluency in Mohawk, and a keen interest in the military.

After John’s mother’s death, Sir William brought a lively Mohawk named Mary (Molly) Brant into his home, ostensibly as housekeeper. In a short time, she was sharing his bed and became a critical element in the baronet’s continued success, as she was an energetic, intelligent clan matron of considerable influence. Her younger brother, Joseph, also entered the household and was treated as another son by Sir William; Joseph Brant became John’s life-long friend. The union of William and Mary added seven more children to the mix, two sons and five daughters – truly a complex family.

In 1760, young Johnson was appointed a captain in Albany County’s 2nd Regiment. His first independent command came during the 1763 Pontiac Uprising when he led a company of Iroquois warriors ̶ including Brant ̶ and Yorker rangers into Indian Territory to subdue a defiant Delaware faction. He ended his New York militia career in 1775 as the major-general of northern New York’s militia.

Although Sir William’s knighthood was hereditary, there was doubt that the title would pass to his illegitimate son, so when John was sent to Britain to expand his horizons and rub shoulders with the gentry, it was a relief that he was received by King George and knighted in his own right. Doubtless the honour reflected the ongoing accomplishments of his father, but it was no less welcome for that.

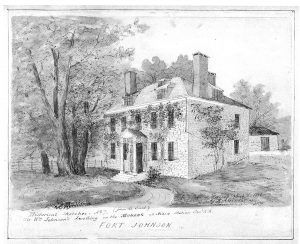

Upon returning, Sir John lived contentedly in his father’s old home of Fort Johnson on the Mohawk River with Clarissa Putnam, a Tribes Hill woman, who bore him two children. He was deeply in love, but Clarissa’s humble origins displeased his father, and under pressure, John abandoned her and went courting among New York’s high society. He met and married Mary Watts, and they came to live at Fort Johnson after Clarissa dutifully moved away. To judge from John’s later actions, the loss of Clarissa may have been his first serious misfortune.

In 1774, Sir William died during a critical Native council at Johnson Hall, his new home in Johnstown. Sir John had earlier declined the position of Indian superintendent, so his cousin and brother-in-law, Guy Johnson, took the helm. John was the principle beneficiary of Sir William’s estates, some 200,000 acres which had been accumulated through his Native relationships. John was now one of America’s richest men, although the majority of his wealth lay in land and fees from some 1,000 tenants. Mary Brant returned to her old home at Canajoharie and John moved into the Hall.

When New England’s political unrest spilled over into New York, the Whigs suspected that the Tory Johnsons would remain loyal to the crown, so the militia’s leadership, hitherto a Johnson preserve, was given to men who favoured the rebel cause. Sir John was deposed as major-general, and other loyalists were removed from their posts as Tryon County’s field officers.

Guy Johnson believed he was threatened by Massachusetts radicals and abandoned the Mohawk Valley. He travelled west with his family and his brother-in-law, Daniel Claus, his deputy superintendent. With them went the interpreter John Butler and his son Walter, Joseph Brant, and many other supporters and department employees. Sir John remained behind as the most prominent loyalist in the Valley, and came under intense scrutiny. Johnson Hall was already flanked by two stone blockhouses and he had a palisade built, mounted cannon and began raising a regiment. The Whigs worried that the magic of the Johnson name and the baronet’s belligerent actions would rouse the Six Nations. Whig general Philip Schuyler, a social acquaintance of the Johnsons, decided to neutralize him and marched with four thousand Albany and Tryon County militiamen. Johnson’s several hundred recruits and the garrison at the Hall were no match for Schuyler’s army, and he was coerced into “behaving” and his supporters’ arms confiscated. Johnson had no intention of succumbing to rebel upstarts and covertly continued to build his regiment, but word soon reached Schuyler. Washington ordered the baronet seized, and the 3rd New Jersey Regiment of the Continental Line was dispatched.[1]

Schuyler was the senior officer of the Whigs’ northern Indian Department and knew the deed had to be done cautiously, so as not to alarm the Iroquois.[2] A deputation met with Fort Hunter Mohawks headmen to explain the purpose of the troops marching into the valley.[3] Johnson was forewarned, and although it meant abandoning his pregnant wife and infant son William, he immediately prepared to escape. He ordered the burial of his critically important family papers[4] and parchment land deeds in an iron chest, and had the family’s silver plate interred in the Hall’s front garden. Some 170 men of his nascent regiment[5] prepared to leave the valley, led by three Mohawk guides.[6] As the Continentals marched into Johnstown, they were shadowed by dissatisfied warriors whose parade through the town assisted Johnson’s escape.

Johnson headed directly north through the Adirondacks, and after trekking nineteen days his starving, exhausted party arrived at the Native community of Akwesasne on the St. Lawrence River. After recuperating, he set off to relieve Montreal. En route, his little army grew to five-hundred with the addition of Natives, and Anglo- and Franco-Quebeckers. He arrived a few hours after the city had been relieved by the British 29th Regiment, then set off in pursuit of the retreating rebels, and near Chambly, fell in with Governor Guy Carleton, who immediately issued him a beating order for a regiment, giving the new formation the title, the King’s Royal Regiment of New York.[7]

Sir John was appointed second-in-command of St. Leger’s 1777 expedition. The force was to subdue Fort Stanwix (Schuyler), proceed down the Mohawk Valley to Albany, and join Lt. Gen. John Burgoyne’s Grand Army, which was to advance from Montreal up Lake Champlain. However, St. Leger’s siege of the fort failed and he retreated precipitously to Oswego from where he was ordered to join Burgoyne’s army on the Hudson River. He set off for Ticonderoga, but a junction was never achieved, as Whig militia had destroyed that fort’s docking facilities and removed all the boats. Of course, this was just as well, as St. Leger’s force, including Johnson’s battalion, was saved from surrendering with Burgoyne’s army.[8]

The recovery from the major defeats of 1777 was understandably difficult for the army in Canada, made worse by the behaviour of Governor Carleton who continued to be terribly affronted over his removal from command of the 1777 campaign. Although he had cooperated with Burgoyne, he was distraught with the employment of Natives in active support of the army, something he had striven to limit. In consequence, he distanced himself from the 1778 campaign while awaiting his replacement. This inattention allowed the Natives to take control of the strategy and tactics for a long, bloody season.

Sir John was under pressure for lack of funds, as his request for the usual bounty to raise and outfit a regiment had been denied based on the premise that “under the influence of so respectable a chief as yourself, the enlistments will be made with little expense.”[9] He was also responsible for Quebec’s Secret Service, and when he sent a scouting party to Johnstown, he seized an opportunity, instructing the officers to dig up his chest of papers and deeds and bring them to Montreal. When the chest was opened, it was found that, “The said Papers[,] Parchments &c for a considerable time had laid under water and that the Parchments being entirely rotten and nothing but the Seals thereof remaining and intermixed with the other papers in such a manner that the same were wholly obliterated and destroyed by the wet and quite illegible.”[10] Johnson reported to the new governor, Gen. Frederick Haldimand, that this disaster represented a loss of twenty thousand Pounds Sterling.[11]

The sufferings of the northern frontiers had been so bloody, destructive, and extensive that Congress decided to punish the Six Nations during the 1779 campaign and drive them out of the war. Two large forces were assembled, one in the Mohawk Valley, the second in Pennsylvania. The two forces combined to destroy all the Native communities met on their march and located around the Finger Lakes. A third force from Fort Pitt destroyed the Senecas’ Alleghany villages. Haldimand had been so preoccupied with the threat of a Franco-American invasion that he ignored repeated warnings. In September, accounts from trusted Natives told of the disasters perpetrated by the rebels in Indian territory, which finally roused him to take action, no doubt recognizing that an invasion of Quebec was unlikely at this late date. He appointed Lt. Col. Sir John Johnson to command a relief expedition of five hundred Regulars and Provincials supported by Fort Hunter Mohawks and Canada Indians.

It is difficult to imagine what such a small force would have achieved against thousands of Continentals, but speculation is pointless, as Johnson’s expedition arrived in Indian Territory far too late, well after the Continentals had destroyed a majority of the Six Nations’ villages. The greatly-fatigued soldiers were on their return march and entirely beyond Johnson’s reach.

By 1780, Johnson’s battalion had prospered, but still remained below full strength. He yearned to complete it and raise a second, and, in particular, for the regiment to be raised to the British Establishment, an honour that had been bestowed on another regiment called the Royal Highland Emigrants when it became the 84th Regiment of Foot. Three Provincial regiments in the area of New York City had been placed on a new American Establishment as de facto British Regulars, so his expectations were not unreasonable.[12]

Intelligence was received early in the year that Johnstown area loyalists would be forced into the rebel service, and they requested a guide to lead them to Canada.[13] Johnson saw an opportunity to complete his battalion and requested permission to mount an expedition to chastise the rebels and lead off the loyalists. The governor approved and authorized a force of British and German Regulars, Provincials, and Indian Department rangers with 150 Fort Hunter Mohawks and Canada Indians.

The expedition was a particular success, not only due to the stealth and speed of execution, but also because the local militia regiment, which had been under arms in Johnstown, was dismissed home on May 17, despite warnings that “the enemy are on their way.” However, the Continental colonel commanding the 1st New York Regiment and Fort Stanwix opined that “no body of the enemy was … on this side of Lake Champlen.” In addition, it was crop sowing time and provisions were running short.[14] After the militiamen dispersed, only a small company of State Levies garrisoned the fort in Johnstown.[15]

Upon Johnson’s return to Fort St. John’s on the Richelieu on June 3 he reported to Governor Haldimand, pragmatically listing the considerable destruction and killings that had occurred. Noteworthy was the one hundred and forty-three men who had come away as recruits.[16] Sir John failed to mention a little side-adventure, which was detailed in a deposition of a Tryon militiaman, Thomas Sammons, who had been captured at his family home. He and the other prisoners were marched to Johnson Hall, where he witnessed an interesting event. “I then saw About 40 men[17] march from the Hall and marched direct to Sir John Johnson. [T]her was 3 or 4 Bags with silver plate[18] which had been Buried in the sellar formerly belonging to the Famely of the Johnstons had been buried in 2 Barrels[. T]he Bags were opened[,] t[h]rowed on the Ground and every man was Handed some[,] put in his knacpsack[,] his name put down & then Marched of[f].”[19]

It appears that the silver plate arrived in Quebec intact; however, Sir John’s ill luck continued. Legend has it that he decided to ship the service to Britain, perhaps for safe keeping, or to be liquidated to raise much-needed cash. Historian John Watts DePeyster offers three theories concerning the plate’s demise. One, the vessel foundered in the Gulf of St. Lawrence and the plate was lost. Second, the vessel was intercepted by a Massachusetts’ privateer and the plate taken. Third, the interceptor was a French letter-of-marque. Whatever the case, Sir John had suffered more bad luck and lost the family’s silver plate.[20]

In the fall of 1780, Sir John led a much larger, deeper-penetration expedition into the Schoharie and Mohawk Valleys to destroy the harvests and the rebels’ means of farming. While fighting was limited, the destruction of grains, livestock, and barns was immense, which distressed General Washington who had been relying on these resources to feed his armies.

The following year, Johnson concentrated on managing the Secret Service and worrying over the status of his regiment. The latter caused him great disappointment, as his desire to have the regiment raised to the establishment was denied, and the Royal Yorkers were classed as Provincials with the lower standing this represented.

In 1782, responsibility for intelligence gathering in New York was reassigned. Then, a scandal in the Six Nations’ Indian Department changed the course of Sir John’s life. His cousin, Col. Guy Johnson, was brought down from Niagara to be investigated for financial indiscretions. Because of Daniel Claus’s ill health, Sir John was appointed the Superintendent-General and Inspector-General of Indian Affairs. This was followed by a promotion to Provincial brigadier-general, which gave him rank over the department’s other officers. He was immediately submerged in Native concerns, as a cease-fire had been proclaimed and peace negotiations were underway. Native anxieties proved fully justified, for when the terms of the Peace Treaty of 1782 became known in Canada, the Natives had been entirely ignored. Despite his earlier rejection of this role, Sir John would spend the rest of his life working on behalf of Native peoples.

When it became obvious that the majority of the loyalists who had soldiered or been refugees in Quebec had no hope of returning to their homes in the United States, Governor Haldimand made preparations to settle them in Canada and appointed Sir John as the Superintendent-General of Refugee Loyalists in May 1784, although the majority of his efforts were centered on the Natives.

During the following years, Sir John had many other disappointments; the greatest, however, came when the western regions of Quebec became a separate province known as Upper Canada. Johnson had labored diligently to establish an American-style government for the new settlements and had been recommended as the new province’s lieutenant-governor by Haldimand and his successor, Guy Carleton – Lord Dorchester; however, in 1790, the home government saw the issue differently, not wishing to appoint “a Person belonging to the Province and possessing such large property in it.”[21] One also suspects an American was considered unsuitable.

After suffering two years of frustration due to the antagonism between Governor Carleton and Upper Canada’s lieutenant-governor, John Graves Simcoe, Johnson decided to migrate to England where he hoped to reestablish himself. He received the King’s permission to absent himself from his duties, but his stay in England was disappointing. He was simply another colonial refugee and his and his father’s services and accomplishments meant very little to government and English society. In contrast, the extravagant Lady Johnson was thoroughly engaged with English life and the couple argued about their sons’ education and careers. Like their father, the children yearned to return to Canada, and the parents drifted apart.

Yet another disappointment ̶ his official claim for losses totalled £103,162 Sterling, but the government instituted a sliding scale of major deductions for the larger claims. As a result, he was awarded only £47,000 Sterling, about 46%, although the shortfall was in part compensated for by promises of large tracts of land in Canada. Latterly, he constantly battled to recover a position of wealth, although his stream of expenditures was immense and he was forever scrambling to sustain his extended family ̶ his eleven legitimate children; his widowed sisters and their children; his wife’s widowed sister and her children; and his first love Clarissa and her two children.

Sir John and his family arrived back in Canada in 1796 after a harrowing voyage during which they lost their baggage, part of their furniture, and a new silver plate service.[22] Johnson was appointed a member of the Legislative Council of Lower Canada. He had held this same post earlier for the province of Quebec. He also resumed the role as Superintendent-General of Indian Affairs[23] and remained active in that position until his death.

Judging from his accumulation of mansions, houses,[24] farms, mills, and land, he intended to rebuild his estate to a similar size to that lost in New York State. During the War of 1812, he served as the colonel of Quebec’s Eastern Township’s militia and several of his sons and sons-in-law were officers. During another absence by Lady Mary in England, Clarissa came to briefly visit Sir John, and her son William moved to Quebec and served in various capacities including the military.

The passage of the years took a heavy toll on Sir John, as government officials interfered in Native affairs to his great frustration. His latter days were lonely, as Lady Johnson and several of his offspring had died of natural causes or in the service. When he died on January 4, 1830, aged 88, his financial affairs were in tatters.

The Montreal Gazette[25]reported that Johnson’s funeral “was attended by a larger concourse of people of all classes than ever assembled in the Canadas.” The British 24th Regiment led the procession and the members of the Masonic Lodge were in large numbers to pay tribute to their Provincial Grand Master. Some three hundred Canada Indians attended. An oration by an elderly Kahnawake chief attested to “their very great respect for the character of so great a father to the red children as he who made the roof to tremble had been to them.”[26]

[1] Orders from Washington contained in Gates to Dayton, New York 09May76. “Papers of General Elias Dayton,” New Jersey Historical Society Proceedings, Volume 9 (1864), 179-80.

[2] As an example, this instruction was given to Dayton: “Your men are frequently to be cautioned against offering any insult or abuse to the Indians, as one act of rudeness in a soldier might involve America in a Dangerous war with a Savage Enemy.” General Sullivan to Colonel Dayton, Albany May 17, 1776. “Papers of General Elias Dayton,” 182.

[3] “Commissioners Meet with Lower Mohawk Castle Sachems,” May 20, 1776. Indian Affairs Papers – American Revolution, Maryly B. Penrose, transcriber and editor (Franklin Park, NJ: Liberty Bell Associates, 1978), 56-60.

[4] Schuyler ordered Dayton to search for and examine Johnson’s papers to discover incriminating evidence of Johnson’s loyalty to the crown and his activities promoting resistance to the rebellion. “Papers of General Elias Dayton,”180; Buried papers: Ray Ostiguy research. Deposition of William Byrne, Montreal November 3, 1787. Records of Notary John Gerbrand Beek, Minute No.330. BAnQ Vieux Montreal, CN601,529. Fonds Cour supérieure, District judiciare de Montréal, Greffes de notaires.

[5] Sir John Johnson [SJJ] to Claus, January 20, 1777, transcribed in John Watts DePeyster, Miscellanies of an Officer (New York: C.H. Ludwig, 1838), L.

[6] Declaration of Deputy-Commissary Gumersall, August 6, 1776. New-York Colonial Manuscripts, London Documents, XLVI, 682&83.

[7] Carleton to Germain, July 8, 1776, Library and Archives Canada [LAC], Colonial Office42/35 (Q12), 102 and SJJ to Claus, January 20, 1777, transcribed in DePeyster, Miscellanies, L. Sir John noted that the future raising of a second battalion was approved in the warrant.

[8] For a full account of St. Leger’s expedition, see Gavin K. Watt, Rebellion in the Mohawk Valley – the St. Leger Campaign of 1777 (Toronto: Dundurn Press, 2002) and Gavin K. Watt & James F. Morrison, The British Campaign of 1777, Volume One – The St. Leger Campaign. The forces of the Crown and Congress, Second edition (Milton, ON: Global Heritage Press, 2003).

[9] Burgoyne to SJJ, transcribed in Ernest A. Cruikshank & Gavin K. Watt, The History and Master Roll of The King’s Royal Regiment of New York (Campbellville: Global Heritage Press, 2006), 11.

[10] Byrne deposition.

[11] SJJ to Haldimand, Lachine, November 24, 1778, transcribed in “Letters from Officers of the Royal Regt. Of New York with Returns, etc., 1776-1783.” Library and Archives of Canada [LAC], Haldimand Papers [HP], Manuscript Group [MG]21, B158 [AddMss21818], 42; “An ‘odious’ comparison”: This source suggests that the value of this loss in today’s funds would be £3,140,000, or $4,500,000USF before Brexit. http://inflation.stephenmorley.org/

[12] SJJ to John Blackburn, Montreal, September 6, 1779, “Letters to John Blackburn, merchant, of London, from Sir William Johnson, Bart., of New York, his son, Sir John Johnson, and Colonel Guy Johnson, 1770-1780.” Blackburn Correspondence, British Library, AddMss24323.

[13] Haldimand to Germain, July 12, 1780. LAC, CO42/40, 87.

[14] James F. Morrison, “The Great Conflagration of May 1780 – Part 1,” http://www.rootsweb.com/~nyfulton/Military/greatconflag1 (accessed April 13, 2003). Dismissal of militia: “Papers of Secret Intelligence, n.d.,” Haldimand Papers, B182 (AddMss21842,) 225&26. http://heritage.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.lac_reel_h1737/1514?r=0&s=1 (accessed June 13, 2016); First warning: Klock to Visscher (Fisher), Fort Paris, May 15, 1780, transcribed in Jeptha R. Simms, Frontiersmen of New York (Albany: George C. Riggs, 1883), 2:324; Second Warning: Unknown to Visscher, Caughnawaga, May 15, 1780, Calendar of the Wyman Collection, Benedict Arnold Papers, No.118. New York State Historical Association, Cooperstown, NY.

[15] Thomas Sammons Manuscript held at the Montgomery County Department of History and Archives, Old Courthouse, Fonda, NY. Footnoted by J.F. Morrison.

[16] SJJ to Haldimand, St. Johns, June 3, 1780, LAC, HP, MG21, B158 [AddMss21818], 128-31.

[17] Speculation exists that the men assigned to carry the plate to Quebec were from the colonel’s company, as they are believed to have been recruited from the men working the Johnson Hall estate or were residents of Johnstown who could be considered as confidential employees and friends of Sir John. Yet, a minute study of the colonel’s company’s rolls reveals only eight men who fit that description. See Master Roll, Cruikshank & Watt, King’s Royal Regiment, 167-337.

[18] Silver plate, that is, items for serving food and lighting the table, and likely flatware.

[19] B. Bruce-Biggs research. The silver plate’s recovery was confirmed in The New-York Packet, June 8, 1780; the renowned American historian Franklin B. Hough observed, “the principal object of this incursion was to obtain the silver plate which had been buried by Sir John on his first hasty flight from Johnson Hall.” Haldimand would not have approved or tolerated such a venture. Franklin B. Hough, Gazetteer of the State of New York (Albany: Andrew Boyd, 1872), 403.

[20] John Watts DePeyster, The Life, Misfortunes & the Military Career of Brig. General Sir John Johnson Bart. (New York: Chas. H. Ludwig, 1882), lvii. After the war, Johnson spent four years in Britain. Dissatisfied, he returned to Canada and experienced a harrowing voyage. He wrote to his nephew, William Claus, “I certainly met with every Opposition and Obstacle possible to be opposed to Man – yet, thank God, except for the loss of our Baggage, Plate … “Clearly, the family had purchased a new service. Transcribed in Earle Thomas, Sir John Johnson Loyalist Baronet (Toronto: Dundurn Press Limited, 1986) 139; Johnson to William Claus, November 6, 1796, Claus Papers, MG19, F1, vol.15, 250-53. Somewhat contradicting the story of the lost plate are a pair of candlesticks, reported to have belonged to Sir William, which were private hands in Senneville, Quebec circa 1962. Of course, individual pieces may have been sold prior to the shipment to Britain. The Papers of Sir William Johnson, Milton W. Hamilton, ed. (Albany: State University of New York, 1962), 13:652.

[21] Grenville to Dorchester, January 3, 1790. The Simcoe Papers, E.A. Cruikshank, ed. (Toronto: Ontario Historical Society, 1931), 1:13.

[22] Johnson to William Claus, November 6, 1796 partially transcribed in Thomas, 139.

[23] Earle Thomas, “Biography of Sir John Johnson,” Dictionary of Canadian Biography, VI (1821-1835) Thomas succinctly describes the many complications of the department’s administration and the sources of unrest and dissatisfaction among the Native nations.

[24] In the spring of 2016, Sir John’s house in Williamstown, Ontario was awarded a $450,000 restoration grant. See http://www.cornwallseawaynews.com/News/2016-06-13/article-4558018/SIR-JOHN-JOHNSON-HOUSE%3A-Nearby-historic-site-will-receive-$450k-upgrade/1

[25] Montreal Gazette, January 11, 1830; Sir John’s Native name was Owassighsishon, which means “He Who Made the Roof to Tremble.”

[26] A commemorative plaque recognizing Sir John Johnson as a veteran of the War of 1812 was unveiled on June 23, 2016 at the Johnson family vault. Four other veterans of that war are interred therein. (1) His son-in-law, Colonel Edward Macdonnell, married to the eldest daughter Anne (Nancy), who had been Quarter-Master General to the Forces serving in North America. (2) His son, Robert Thomas Johnson, Captain, 100th Regiment of Foot, who drowned crossing the ice on the Richelieu River on March 31, 1813. (3) His son, John Johnson Junior, Major and then Lieutenant-Colonel of the 6th Battalion of the Eastern Townships Militia under the command of his father. (4) His son, Adam Gordon Johnson, 3rd Baronet, Secretary, then Deputy Superintendent (1814) of Indian Affairs and lieutenant-colonel of the 6th Battalion of the Eastern Townships Militia. In 1814, Adam was lieutenant-colonel of four companies of Native warriors under the overall command of his father. Email, Adelaide Lanktree and Ray Ostiguy of the Sir John Johnson Branch, United Empire Loyalists of Canada, to the author, June 16, 2016.

One thought on “Sir John Johnson, The Hard Luck Baronet”

This is a wonderful account of the history of Sir John Johnson actions during the Revolutionary War. Articles such as this one and the books written by Mr. Watt have immensely helped me in my search to understand the life and times of my Loyalist ancestors.