The war on the New York frontier did not end with Burgoyne’s surrender at Saratoga in October 1777. Year after year the conflict raged on, taking on the characteristics of a civil war. This conflict was not fought by grand armies facing off in titanic struggles, but rather initiated by British Loyalists garrisoned in western New York and Canada, and their Iroquois allies, sometimes opposed by local American militia units. For the next several years, the settlements of German Flats, Springfield, Cobleskill, Canajoharie and Cherry Valley were among those attacked, their inhabitants losing their farms, crops and livestock to the raiders. In 1779 General Washington authorized Gen. John Sullivan to conduct a campaign to destroy the Iroquois’ ability to remain in the war. Their massive raid though central New York inflicted destruction similar to what the American settlements had been sustaining. However, the Iroquois warriors retreated before the advance of the invasion and regrouped around their British allies at Fort Niagara. They survived to fight another day, and the next year they carried out their own retribution.

In May 1780, Sir John Johnson, son and heir of Sir William Johnson, led his King’s Royal Regiment and Loyalists drawn from Maj. Edward Jessup’s King’s Loyal Americans and Maj. Daniel McAlpin’s American Volunteers, along with a group of Mohawk warriors, south from Crown Point. This force totaling 528 men headed straight for Johnstown, where on May 21 they scattered a small contingent of Tryon County Militia men opposing them, capturing twenty-seven. They burned 120 barns, mills and houses, gathered up 143 local Loyalists and headed back to Crown Point.[1]

October represented the culmination of the 1780 campaign. In late September Sir John Johnson returned to the area from Oswego with a force of 893 men, including 185 British regulars, 156 Rangers led by Lt. Col. John Butler, and 287 Loyalists from the King’s Royal Regiment. They were joined by 265 Iroquois led by Joseph Brant.[2] After some delays this force headed southeast. They entered the Schoharie Valley from the south on October 17 and then proceeded north. Failing to capture the Upper, Middle and Lower Forts in the valley, they concentrated on destroying homes, farms and crops, much as Sullivan had done the year before. Reaching the Mohawk River near Fort Hunter they turned west, creating a similar path of destruction. Johnson’s original strategy was to hook up with the second invading force coming southward from Canada and jointly attack Schenectady in a pincers movement. His late start foiled that plan.[3]

Entering the Mohawk Valley, they were pursued by a force of Albany and Tryon County Militia, as well as elements of Levy regiments, all under the command of Gen. Robert Van Rensselaer. Van Rensselaer’s force caught up with Johnson at Klock’s farm on October 19 and engaged them in a confused battle that ended when Johnson’s men left the field as darkness descended. The invaders won the race to their boats hidden on Onondaga Lake and headed back to Oswego, escaping the pursuing rebels. They had made a wasteland of two valleys in the heart of rebel territory at the surprising low cost of nine killed, two wounded and fifty-three missing.[4]

The second part of the British fall campaign was led by Maj. Christopher Carleton, a veteran of the border wars, who advanced south along Lake Champlain with 518 British regulars and 315 Provincials from various Loyalist regiments.[5] Among the Loyalist leaders serving under Carleton were Maj. Edward Jessup, Capt. William Fraser, and Capt. John Munro. All were familiar with the rebel territory they were about to enter. Jessup and his brother Ebenezer had received large grants along the upper Hudson River from several New York colonial governors, and returned the favor by their faithful loyalty to the British cause.[6] Fraser, whose family emigrated from Ireland as tenants of Sir William Johnson, purchased a lot in the town of Ball’s Town[7] in 1772 on the same day as his soon-to-be nemesis, Lt. Col. James Gordon. Munro, a retired British half-pay officer, parlayed his French and Indian War service into an 11,000 acre land grant along the Vermont border, where he used his position as an Albany County Justice of the Peace to confront Ethan Allen and the Green Mountain Boys over disputed land titles in the Hampshire Grants in the early 1770’s.[8]

More importantly, they knew the people who lived along their invasion route — their Tory friends and Rebel enemies. They could count on the former for protection as they moved through the countryside. For the latter they sought revenge for the harassment they and their families had endured throughout the war at the hands of the Albany County Militia, the largest militia force in New York State.

This Loyalist force of 833 men left St. John’s on the Richelieu River on September 28 in eight ships and twenty-six smaller bateaux and sailed south.[9] On October 2 they camped at Valcour Island, the site of the battle with Benedict Arnold’s navy four years before. Here they were joined by thirty Fort Hunter Mohawk warriors under the leadership of Lt. Patrick Langan from the British Indian Department and Mohawk war Chief John Deserontyon. On October 5 a party of 108 St. Regis Indians arrived at Carleton’s camp at Split Rock Bay on the west side of Lake Champlain, completing the assembly of the raiding party which now totaled 971 men. On October 6 Captain Munro split off near Crown Point, leading a detachment of 195 provincials and Indians south from Bulwagga Bay, following the same trail used by Sir John Johnson during his spring campaign.[10]

Carleton’s main body moved south along the lake past Fort Ticonderoga, which had not been regularly occupied by either side since Burgoyne’s surrender. They moved into South Bay and arrived at Skenesborough (Whitehall) on October 8. The next day they proceeded south along the trail past an abandoned blockhouse and soon arrived in front of Fort Anne, which was defended by Capt. Adiel Sherwood and seventy four militiamen. This fort and its defenders were typical of the small, undermanned obstructions put in place along the frontier to protect the countryside from invasion. The decrepit condition of the Fort Anne was confirmed by the British. Openings in the logs were cut to fire through but “so ill was this done that those on the outside had an equal chance with the garrison as the holes were low enough to be fired into from the outside.” Needless to say, Captain Sherwood surrendered and was taken prisoner along with the militiamen.[11]

On the morning of October 11 Carleton’s invaders advanced toward Fort George at the southern end of the lake of that name. The fort’s commander, Capt. John Chipman, had no knowledge of the size of the force bearing down on him, but he sent out a scouting party of forty-eight men under Capt. Thomas Sill to assess the situation. Sill’s men were soon surrounded by the Indians. The result was another bloody encounter at Bloody Pond. Twenty-seven troops were killed, including Sill, eight were captured, and thirteen fled into the woods. This was the only action during the entire campaign that resulted in significant casualties.[12]

Chipman was forced to surrender the fort along with forty-five of his men, all from Col. Seth Warner’s Continental Regiment. The prisoners were marched out and “the Savages were admitted to plunder the place, a thing they always look upon as their undoubted right.”[13] On October 12 Carleton’s force, swollen by well over one hundred prisoners, began their trek northward along the west side of Lake George. They arrived back at Crown Point on October 16 where they waited for word from Captain Munro, who had not been heard from since he had left them ten days before.

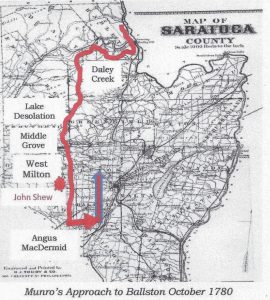

On October 7 Munro led his smaller force of 195 men, fully loaded with supplies and ammunition, seven miles south from Bulwagga Bay, traveling east of Bulwagga Mountain. This contingent consisted entirely of provincial troops and Indians, including Munro’s and Anderson’s companies of the King’s Royal Regiment, Fraser’s Rangers and Deserontyon’s Indians led by Langan.[14] They followed a trail that eventually headed westward, most likely skirting Eagle Lake and Paradox Lake. Turning south along Schroon River they followed an interior trail west of the river and along the base of Crane Mountain reaching the Hudson River west of the later village of Warrensburg. Continuing south they reached the confluence of the Hudson and Sacandaga Rivers on October 11.[15]

Making his way along the Sacandaga, Munro turned inland at the outlet of Daley Creek where he soon passed the Indian trail marker known as Tory Rock.. Crossing the Kayaderosseras Mountains the invaders arrived at Lake Desolation the next day.[16] Munro now had a decision to make. Several choices presented themselves. His primary objective may have been to coordinate with Sir John Johnson’s raid in the Schoharie and Mohawk Valleys. Munro’s presence could be used to draw American troops away from Johnson, while also causing some destruction of his own.[17] He had sent scouts to find Johnson and coordinate their plans but they had not returned. A secondary objective, the town of Schenectady, was judged to be too heavily defended to be attacked.

Munro proceeded down the mountain from Lake Desolation to Kayaderosseras Creek where his men set up camp, probably along the creek between the current hamlets of Middle Grove and West Milton. While encamped in these woods a third option presented itself. Munro sent Capt. Fraser to scout his old neighborhood around Ballston. An advance in that direction could provide a double benefit. In addition to destroying a farming community with its mills and recent harvest, Munro and his party would have the opportunity for some payback. Ballston was the home base for the well-known 12th Regiment of the Albany County Militia led by Lt. Col. James Gordon and Capt. Tyrannus Collins.[18]

The invaders’ animosity toward these influential men of Ballston went back to the very beginning of the war. Gordon and Collins, and the militiamen they led, had been zealous in tracking down Tories and making life miserable for their families throughout the war. In May 1777, as Burgoyne’s invasion loomed, they forced Maj. Daniel McAlpin, a local Loyalist officer, to flee to Canada, confiscated his property, and herded his wife and children to confinement in Albany.[19] That same spring Collins had captured William Fraser and his brother Thomas along with forty Tories on their way to join the British in Canada. They had been imprisoned in Albany but were soon able to escape and join Burgoyne’s invasion force.[20]

Gordon was the patriarch of the families that had settled along Middleline Road in Balls Town, a tight-knit pioneer community just forming in the Kayaderosseras Patent north of Albany. The Patent, originally granted by Queen Anne in 1708 had only recently been surveyed and opened for settlement. Gordon had emigrated from Ireland in 1758 and teamed with Robert Rogers and local merchants to supply goods to the military during the French and Indian War.[21] In 1772 he purchased 1000 acres along “The Middleline” where he soon constructed saw and grist mills to support the new settlers moving in from Connecticut. As war approached, he became a leader of the local Committee of Correspondence and served as lieutenant colonel of the 12th Regiment of the Albany County Militia. However, his partisanship extended beyond his military actions. As a member of the New York Assembly he had advocated for harsh treatment of captured Loyalists and had supported the 1779 Confiscation Act. That act called for the banishment of many prominent men of New York who had sided with the British, and sentenced them to death without clemency if they returned.[22] In his later report on the raid, Munro cited Gordon’s support of this law as justification for his actions against him.[23] Munro made his decision. “I found it necessary to make a decent on Ballston, and proceed to join Major Carleton without loss of time.”[24]

On Monday, October 16, Munro broke camp and began his march south along the path now known as Paisley Street. The Scottish settlers in this area could be counted on for loyalty to the King.[25] Along the way Fraser returned from his scout with information that Ballston was well-protected by local militia, including a contingent of the 2nd Militia Regiment led by Maj. Abraham Swits of Schenectady. Fraser may have also been able to tell Munro that both Gordon and Collins were back at home. Gordon had just returned from a session of the New York Assembly, while Collins had returned after leading his militia north in a fruitless pursuit of Major Carleton’s invading force.

As Munro approached the current Galway-Milton town line, his troops surprised and captured two men. These men were most likely acting as scouts for the militia, although they were quick to claim they were just two friends out hunting. Two of the Mohawks immediately recognized one of the men, with fatal consequences. The Indians were brothers, known as Aaron and David Hill, noted Mohawk warriors. The man they recognized was John Shew. Shew had been captured in 1778 by these same brothers, and had managed to escape. Now two years later, he was not given another chance. As his companion Isaac Palmatier watched, he was bound to a tree and dispatched by a tomahawk blow to the head. Munro’s raid had claimed its first victims—one dead, one captured.[26]

As night fell the invaders continued south and entered the District of Ballston along the path that became Hop City Road. Guided by James McDonald, a Loyalist sympathizer, they generally followed a path, later named Devil’s Lane, eastward until they reached the clearing of James Gordon at about midnight. There Munro divided his forces, sending William Fraser and his provincials across the Mourning Kill to the cabin of Capt. Collins. Munro deployed the 130 soldiers of the King’s Royal Regiment, dressed in their red uniforms, around Gordon’s home. These men were accompanied by the thirty Mohawks led by Langan and Deserontyon. It was apparent that their mission was not random destruction. Having determined to attack Ballston, their first goal was to target the leaders of the local Militia.[27]

Gordon was asleep in his framed home with his wife Mary when, around midnight, he was startled awake by the sound of bayonets crashing through his bedroom window. Running into the hallway he was confronted by an Indian with hatchet raised, only to be saved from death by the intervention of Capt. Munro.[28]

Being a man of some means, the family was not alone. His household included two farmhands, Jack Galbraith, an Irishman, and John Parlow. At least four slaves were also part of Gordon’s household — Nero, Jacob, Ann and Liz. Jacob had served in Burgoyne’s army and had been taken prisoner by the Americans. Gordon and all his farmhands were taken except Liz, who escaped.[29] Gordon’s four-year old daughter Melinda later recalled the scene. Her memories of this night remained with her, as did her memories of her father.

He stood shivering in the cold, and Langdon took out of his knapsack a blanket coat and gave it to him. I recollect of being in my father’s arms out of the door in the moonlight, when he stood under the charge of Langdon. I recollect awakening some time afterwards by the side of a log heap, in company with my mother and Liz, where they had hid themselves.[30]

At the same time, Fraser and his thirty-four Loyalist rangers had crossed the Mourning Kill to Collins’ log home. Tyrannus, head of one of several families that had moved to Ball’s Town from Richmond, Massachusetts, was there with his fourteen-year-old son Manasseh and his female slave. Tyrannus barred the door long enough to allow his son to escape through an upstairs opening in the logs, intended for a future window.[31] Tyrannus, injured by the thrust of a tomahawk through the door, was captured along with his slave.[32]

Collins’ nephew, Isaac Stow, was Gordon’s miller (and Tyrannus Collins’ nephew); he was not so fortunate. Five of Fraser’s men had crossed the Middleline to capture Stow, who was at home with his wife Sarah and their ten-month-old daughter Clarinda. Stow was detained, but bolted to warn Gordon about the attack. It was too late for him to save Gordon and it turned out to be too late to save himself. “An Indian sent his spear at him and struck it in his back, then caught it and held him, and smote his tomahawk into his head.”[33] As his uncle and his employer looked on, he was scalped, dead at the age of twenty-five. His wife and daughter escaped by wading across the creek and hiding in the woods.[34]

The three parties of Munro’s invasion force now reunited and moved north along the Middleline, coming next to the cabin of Thomas Barnum. Barnum had moved to Ball’s Town soon after marrying Achsah Benedict in 1772, and they had three small children. His family may have sought refuge in a safer location, since no mention is made of them. Barnum was captured and his home pillaged. Across the road Barnum’s mother Jerusha Starr Benedict was living with her husband Elisha Benedict, Barnum’s step-father, and their four sons. The oldest, Caleb, aged twenty-two, served as an ensign in the militia under Captain Collins. Younger brothers Elisha, Elias, and Felix served as enlisted men in the same company. All were captured except Elisha, Jr. who “escaped with only the clothing on his back.”[35] Their slave Dublin was also taken.

At the foot of the hill known as Pierson’s Ridge lived Edward Watrous, who had just turned twenty-seven. He had married Susannah Pierson in 1777 and they had two children. It is possible that his family had retreated to Richmond, Massachusetts, the former home of Susannah’s parents. Edward stayed on to protect his home and serve in the militia. He was captured and his home ransacked, but not burned. Across the road at the crest of the hill stood the cabin of Edward’s father-in-law Paul Pierson, who at fifty-four was twice Edward’s age and too old to actively serve in the militia. Paul and his son John were taken and the Indians proceeded to grab everything of value, including the livestock, which was herded along the road as they proceeded northward.

Moving downhill the attackers came upon the home of John Higby, head of yet another family from Richmond, Massachusetts. John’s son, Lewis, was at home and was captured along with his father. Higby’s cabin was put to the torch, the first home to be burned. The burning of Higby’s cabin may have been a godsend for the family of Jonathan Filer. Seeing the flames from his neighbor’s house, he hurried his family into the woods for safety. The Mohawks attempted to burn the house, but Filer’s mother-in-law, Granny Leake, rushed in and quenched the fire.[36] The path now descended until it approached a creek where James Gordon and George Scott, his brother-in-law, had built a saw mill six years earlier, in 1774. At the saw-mill Munro detached fifty men, mostly rangers under the command of William Fraser, to cross the stream and approach the cabin of Scott. The main body continued north.

Scott was awakened by his barking dog and, seizing his gun, opened the door of his cabin, only to be confronted by Fraser whom he knew from his first years in the settlement. Fraser, apparently trying to save the life of his old acquaintance, shouted “Scott, throw down your gun or you are a dead man!”[37] Not responding quick enough, three Mohawks who had accompanied the party let loose their tomahawks, striking Scott on his head. The Indians proceeded to pillage the home, leaving Scott’s wife, Jane, to minister to her wounded husband (he survived). Their six-year-old son, James, fled into the woods, and was eventually reunited with his mother.[38]

After this half-hour excursion, Fraser’s detachment reunited with the main body and proceeded north, crossing a small stream today known as Gordon’s Creek, and climbing up the hill into the current town of Milton. At the crest of the hill lived George Kennedy and his twenty-two-year-old pregnant wife Mindwell, the daughter of John Higby. George was suffering from an injured foot, the result of an altercation with an axe. That did not exempt him from being taken, joining the growing number of captives. Mindwell managed to escape into the woods. Two weeks later, her first-born child was delivered, and her husband was there to witness the event, as we shall see.[39]

Up the road from the Kennedys lived Jabez Patchen. Jabez was at home with his seventeen-year-old son Walter and his son-in-law Enos Morehouse, who had married his daughter Sarah in 1774. These men were able to escape through a back window and hide in the cornfield, but Jabez was captured. His house was spared the flames.[40]

It was now about 4 A.M., two hours before dawn. The next family to fall victim was that of Josiah Hollister, his cabin lying in a slight hollow along the east side of the road. This was his first year in Ballston, having moved from Sharon, Connecticut, with his wife Mehitable (Andrews) and their two young children, Samuel and Ruth. Loyalist soldiers burst through his door telling him to leave the house immediately before the Indians arrived. Josiah described what happened next in his journal:

I took up my little son, my wife took the other child, and we left the house. They bade me give the child to my wife, but the child clung fast around my neck. I asked them to show some pity; “What can this woman do with two small children.” One presented his gun to my breast and swore an oath that he would not be plagued with me any longer. My wife begged them to spare my life. Another struck up the muzzle of his gun and hauled me away to the guard. But judge what my feeling were at this time to see my house in flames, my wife and children turned out of doors, almost naked; myself hauled away among savages and men more inhuman than they.[41]

Josiah Hollister was related through marriage to Ebenezer Sprague whom he had known in Sharon, Connecticut. It was Ebenezer who had helped Josiah get settled earlier that year, building a cabin just south of the Sprague home. Although at sixty-nine Ebenezer was too old to serve in the militia, he was not too old to be taken captive along with two of his sons, John and Elijah. Together the three stood and watched as their home went up in flames.

Two of George Kennedy’s brothers, Thomas and John, lived on the west side of the road north of the Spragues. Thomas was captured at the same time as the Spragues, but John, alerted by the flames from his neighbors’ homes and crops, was able to escape into the woods with his wife, Hannah. For some reason, the raiders passed by John’s home without torching it.[42]

The last settlement along Middleline Road before it crossed the Kayaderosseras Creek were a cluster of homes of the Wood clan, perched on a slight rise later known as Milton Hill. Two of David Wood’s five sons lived in the path of Munro’s invaders. Stephen and his family were away, but their house, barn, and 800 bushels of wheat were destroyed.[43] Stephen’s younger brother, seventeen-year-old Enoch, and their hired man Cyrus Fillmore were captured. Just as the Loyalists were moving off from the Wood property, Fillmore seized the opportunity to escape. He later filed for a pension in 1832, and in his wife’s widow’s application in 1847 she mentioned that Cyrus was a relative of Millard Fillmore, a rising New York politician and future President of the United States.[44]

Munro’s men then marched down the hill where they forded Kayaderosseras Creek. It was here that Munro displayed his own skill in dealing with the Indians to solve a problem that had developed during the day’s march. George Kennedy’s foot injury had so debilitated him that he allegedly begged to be put to death. For both Paul Pierson and Ebenezer Sprague, their age had caught up with them, and Paul’s young son John also could not keep up. The Indian answer to this problem would have been instant death, but Munro proposed another solution. He suggested releasing the four men, allowing them to return to their homes.[45]

At the same time, to assuage the Mohawks, he allowed Capt. Deserontyon to select a number of men for adoption. Adoption was a long-standing practice among the Iroquois to replace warriors lost in war. Deserontyon chose ten men—the four Benedicts, Thomas Barnum, John and Lewis Higby, Elijah Sprague, and Gordon’s slave, Nero.[46] The next morning, October 18, Munro released the four invalids in the vicinity of Lake Desolation, five miles earlier than the pre-arranged location to forestall the Indians from dropping back to inflict their own justice.[47]

A firsthand narrative from the pension records of a militiaman in the pursuit of the invaders, although written over fifty years later, may well be the most accurate account of the futile effort.

All the Whigs able to bear arms in Ballston were called out to pursue the enemy. He the said David How and others volunteered and marched in pursuit to the Sacandaga Mountains near Lake Desolation when he and his associates met several prisoners returning home who had been released by the British on account of their inability, through age and infirmity, to march on the retreat. These prisoners, three of whom were Pierson, Kennedy, and Sprague, brought from Col. Gordon directions to the party in pursuit not to continue the pursuit, but to return to Ballston as the British officers had put the prisoners captured at Ballston into the custody of the Indian with orders to kill them in they should be attacked. The said How and his associates were ordered back and returned to Ballston.[48]

For the families now left to carry on without their husbands and fathers, it would be a difficult time. In the days after the raid many of them gathered at the Ballston fort, and slept in the woods down the hill near the outlet of Ballston Lake having lost their homes, crops and livestock. Each family made their own arrangements. Some moved in with relatives or neighbors in Ballston or surrounding towns. Others chose to move back to family homes in New England. Twenty-six men captured along Middleline Road were taken to Canada. The militiamen were imprisoned and the slaves sold. Lieutenant Colonel Gordon and several of the captured militia officers served their time under house arrest in Montreal and Quebec. Gordon himself later escaped, but most remained in Canada until released at the end of the war. Their families would wait as long as two years to see their loved ones again.

[1] Gavin K. Watt, Burning of the Valleys (Toronto: Dundurn Press,1997), 78.

[2] Ibid., 164.

[3] Ibid., 162.

[4] Ibid., 337.

[5] Ibid., 95.

[6] Henry Griswald Jesup, Edward Jessup and his Descendants (Cambridge: John Wilson and Son, 1887), 204.

[7] This settlement was first known as Ball’s Town, named after the first settler-developer Rev. Eliphalet Ball. In 1775 it became the District of Ballston, and later the Town of Ballston. I use this latter term in reference to events that occurred during the war.

[8] “John Munro,” Dictionary of Canadian Biography, http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/

[9] Watt, Burning of the Valleys, 95.

[10] Elizabeth Cometti, The American Journals of Lt. John Enys (Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, 1976), 37.

[11] Ibid., 44.

[12] Watt, Burning of the Valleys, 104.

[13] Cometti, Enys Journal, 46.

[14] Watt, Burning of the Valleys, 94.

[15] Nathaniel Bartlett Sylvester, History of Saratoga County New York (Philadelphia: Everts & Ensign 1878), 70.

[16] William L. Stone, Reminiscences of Saratoga (New York: Worthington Co.,1880), 413n.

[17] J. Fraser, Skulking for the King (Erin, Ontario: The Boston Mill Press,1985), 65.

[18] Watt, Burning of the Valleys, 120.

[19] Fraser, Skulking for the King, 44.

[20] Ibid., 38.

[21] Josephine Mayer, “The Reminiscences of James Gordon,” New York History 17, no. 3 (1936), 316.

[22] “New York Confiscation Act of 1779” http://archives.gnb.ca/exhibits/forthavoc/html/NY-Attainder.aspx?culture=en-CA.

[23] Ernest Cruikshank and Gavin Watt, The Kings Royal Regiment of New York (Milton, Ontario: Global Heritage Press, 2006) 59.

[24] Munro’s Supplementary Report, November 20, 1780 in The King’s Royal Regiment, 59.

[25] Booth, John Chester. History of Saratoga County (Originally Unpublished, 1858), 93. This history was edited and printed in 1977 and a copy is located at the Saratoga County Historical Society in Ballston Spa, New York. Excerpts were also published in Edward F. Gross’ Centennial History of Ballston Spa in 1907.

[26] Simms, Jeptha. The Frontiersman of New York Vol II (Albany: Geo.C.Riggs,1883), 479.

[27] Watt, Burning of the Valleys, 124.

[28] Ibid.,125.

[29] Frank Mackey, Done with Slavery – The Black Fact in Montreal 1760-1840 (Montreal: McGill-Queens University Press, 2010), 126.

[30] Edward F. Grose, Centennial History Of Ballston Spa, Mrs. Waller’s Story (Ballston Spa: The Ballston Journal,1907), 40.

[31] James Scott, “Memoranda of Reminiscences, 1846,” The Bulletin of the Fort Ticonderoga Museum, Vol VII, no.4, (July 1946), 16.

[32] Booth. History of Saratoga County, 93.

[33] “The Journal of Josiah Hollister” in Ellis James Alfred, History of the Bunn Family of America, (Chicago: 1928), 335.

[34] Watt, Burning of the Valleys. 126.

[35] Ancestry.com. U.S., Revolutionary War Pension and Bounty Records Warrant Application Files 1800-1900, Elisha Benedict, roll no. 211, file W12183.

[36] Booth, History of Saratoga County, 95.

[37] Ibid.

[38] Scott, Memoranda of Reminiscences, 18.

[39] Booth, History of Saratoga County, 96.

[40] Ibid.

[41] “The Journal of Josiah Hollister,” 335.

[42] Booth, History of Saratoga County, 96.

[43] Ibid.

[44] Ancestry.com. U.S. Revolutionary War Pension and Bounty Records Warrant Application Files 1800-1900, Cyrus Fillmore, roll no.3529.

[45] Watt, Burning of the Valleys. 132.

[46] “Gordon’s Memorandum, ” in Booth, History of Saratoga County, 99.

[47] Munro’s October 24 Report, in The King’s Royal Regiment, 57.

[48] Ancestry.com. U.S. Revolutionary War Pension and Bounty Records Warrant Application Files 1800-1900, David How, roll no. 1339, file S23706.

5 Comments

The book “Carleton’s Raid” by Ida H. Washington & Paul A Washington, Vermont, 1977, ISBN 0-9666832-0-X, is very helpful in covering this area/event.

Be careful–while it’s the same guy (Christopher, not to be confused with Guy Carleton), Ida Washington’s book, “Carleton’s Raid,” deals primarily with a raid into the Champlain and Otter Creek valleys conducted in the fall of 1778. That force never went further south than the area between Crown Point and Ticonderoga on the lake and Middlebury, VT, on Otter Creek.

A branch of the 1780 raid discussed in this article involved about 300 Indians and a few white officers who headed east up the Winooski/Onion River. They had as an objective the settlements in the upper Connecticut River valley around Newbury, VT. The Americans had been using that area as a source of supplies and a place to stockpile materiel for a proposed invasion of Canada. They also hoped to capture Jacob Bayley and Benjamin Whitcomb, both of whom had prices on their heads. Once the party reached the area of modern-day Montpelier, VT, they heard that Whitcomb, the Continental commander in the area, knew of their approach and had gathered together around 500 men in Newbury. Instead of continuing east the raiders turned south and moved down the White River valley attacking the homes and settlements along with way. Once in the area of Royalton, VT, they turned back north and returned to Canada. The incident has become known as the Royalton Raid and is the subject of an excellent book by Neil Goodwin titled “We Go As Captives.”

Thank you for the more precise information. I appreciate the time you took to check me on this. Christopher has fascinated me for some time. I have never been able to track down the supposed portrait of him in full ‘Indian regalia’, casually mentioned in a couple of sources. He seems to have been very effective – and ‘on the ground’ – with his men. Is oddly unmentioned in Indian Department stuff. Briefest obit notice in Montreal. Never have found when his wife (Lady Elizabeth Howard, sister-in-law of Guy Carleton Lord Dorchester) returned to England, although her will (?statement of estate disposal?) exists and is uninformative…..

The 1778 raid is something of a pet project of mine. I organized the bicentennial reenactment of one of the battles in 1978 and have explored some of the routes traveled and sites where things happened.

For more on Christopher Carleton, you might try contacting Gavin Watt. He has done considerable research and written a number of books on the role of Canada in the Rev War. Just do a search for his name and his website and contact info will come up. Good luck.

Many thanks for this account. I lived in Burnt Hills for 26 years, teaching archaeology at the University at Albany. During that time I excavated on the Saratoga battlefield and ran research programs around Lake George and in the Mohawk Valley. By coincidence I was back in the area yesterday, driving on Middle Line Road, Devil’s Lane, and Hop City Road. Now I wish I read your article before, rather than after, I revisited the Town of Ballston. I will be back to give another lecture at the battlefield on October 16, so perhaps I’ll have time to visit Ballston again, this time with a fresh perspective.