The definitions of joint command of land, maritime, air and other forces as practiced by the United States military today were unknown to those who practiced warfare in the eighteenth century. However, the concepts outlined in contemporary definitions were known to military practitioners during that period.[1] General Washington understood the importance of unifying his efforts with his French Allies. With no American Navy to speak of, Washington relied on French naval or maritime power to support his campaign design and that of the French land forces. While Washington had no direct command authority over the French Navy he worked diligently to integrate the power of the French maritime and land forces into his campaign plans.

During the important commander’s conference with General Rochambeau at Wethersfield, Connecticut, on May 22, 1781, Washington demonstrated an understanding of the joint and multinational nature of the American Revolution and the importance to his success of his allies and their military capabilities. At Wethersfield, Washington and Rochambeau decided on two courses of action for the 1781 campaigning season. One course involved an attack on the British base in New York, another focused on British forces in the south. Both depended on French support and specifically on French maritime support and cooperation. Washington and Rochambeau decided to move their land forces to threaten New York because, as Washington explained to Gen. Nathaniel Greene, commanding American southern forces, “I have recently had an interview with the Count Rochambeau, at Wethersfield. Our affairs were very attentively considered in every point of view, and it was finally determined to make an attempt on New York, with its present garrison, in preference to a southern operation, as we had not decided the command of the water.”[2]

The Franco-Americans allies achieved success during the Yorktown campaign because they were able to effectively apply command and control concepts codified today in joint military doctrine. The effective forms of joint and multinational command and control practiced today have their roots in the arrangements outlined and implemented by Generals Washington and Rochambeau and Admirals De Grasse and De Barras during the Yorktown campaign of 1781. The practices implemented by these commanders were often relearned over the years since then, and are now part of standard U.S. joint and multinational military doctrine.[3]

The European powers, with established governments and standing military organizations, adapted their systems to support the military requirements of the American Revolution. The Americans, with no central government and no national military structure, created one beginning in June of 1775. The Yorktown campaign six years later was a joint and multinational operation based on current definitions.[4] By the time of the Yorktown campaign in 1781, the governments of the United States and France fielded military forces in an alliance arrangement based on a treaty signed in February of 1778. At the time of the Yorktown campaign, Britain was at war with the United States, France, Spain and the Dutch, employed auxiliary land troops from the German principalities and participated in loosely structured coalitions with selected Native American tribes. The American Revolution was a multinational military event.

Command and control arrangements are not static depictions of relations between commanders. They must meet the commander’s needs to best support the design or concept of operations envisioned, yet consider specific national sensitivities when involving multinational forces. Command and control arrangements constantly evolve to allow commanders to effectively deal with changing conditions.

The Franco-Americans allies employed a parallel command structure during the Yorktown campaign.[5] This structure involved national command lines and coordination between senior national commanders. Prior to arriving in North America, the French government carefully worked out Rochambeau’s relationship with Congress, Washington, and the governors and major generals in the Continental Army and American Militia. As the only lieutenant general, Rochambeau “stood second only to the President of Congress and the commander-in-chief.”[6] Technically, Rochambeau was subordinate to Washington, but Rochambeau had years of military education and experience on the battlefields of Europe and carefully considered the interests of his nation.

While he was not under Washington’s direct command, Rochambeau deferred to Washington while protecting French national interests and forces he commanded. This structure did not provide for direct unity of command[7] as currently defined. However, if commanders work toward the same objectives and establish trust,[8] they can achieve unity of effort.[9] This structure worked for the Franco-Americans during the Yorktown campaign because of the common view of the mission and the trust between the key military commanders, Washington, Rochambeau, De Grasse and De Barrras.

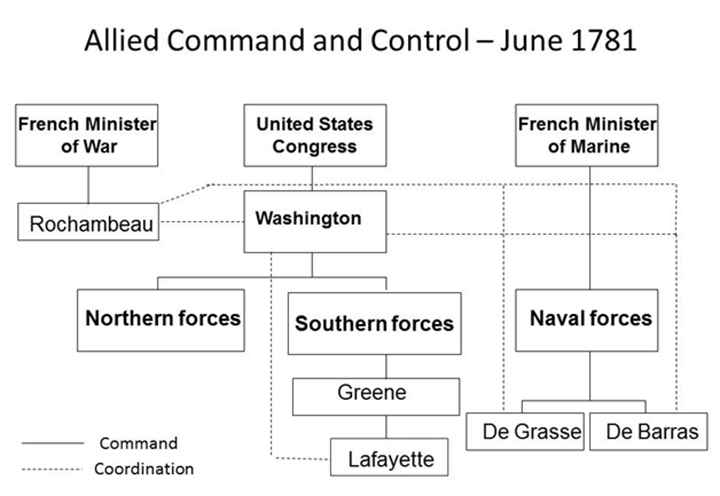

Figure 1 above is a graphic depiction of Allied command and control during June of 1781 as the Yorktown campaign developed from a commander’s concept to execution. The solid lines depict command while the dotted lines depict coordination. Not reflected on the graphic are the state militia forces. Washington and his subordinate commanders relied heavily on the militia to augment the Continental forces. Militia forces were under the command of the state governors and augmented Continental forces when called to active duty for various periods of time based on orders and circumstances. Militia did not always remain in the field for the time specified in their call up orders; properly equipping them for field duty was a constant challenge.

During the month of June 1781 Rochambeau was moving the bulk of the French land forces from Newport, Rhode Island to the Hudson River Valley to link up with Washington’s forces. Washington had notional command of the French land forces in North America under Rochambeau. In reality, command was exercised by Rochambeau’s consent as empowered by the French Government. This insured that Rochambeau protected French national interests when directly supporting American military operations. The dynamic environment had multiple considerations. Rochambeau left about 500 land forces in Newport to serve as land security for the French naval forces remaining there upon his departure. Admiral De Barras assumed command of the French fleet in Newport during May and had his own views on how to most effectively employ his forces. Admiral De Grasse commanded the French fleet in the Caribbean, conducting operations there during the spring and into summer, and had a secondary task to support North American operations.

Nathaniel Greene’s southern forces were actively campaigning in the Carolinas. Because the southern theater extended from Maryland south, Greene exercised command over Lafayette, but Lafayette had orders from Washington to engage the British forces operating in Virginia. Greene understood the importance of Lafayette’s operations there to the overall success of the southern campaign. When the Pennsylvania brigade reinforced Lafayette on June 10, Greene allowed him to retain and employ all his forces in Virginia.

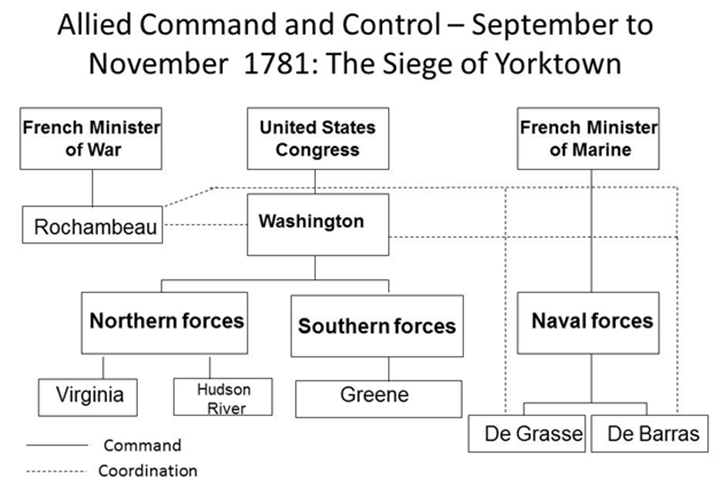

Figure 2 above is a graphic depiction of Allied command and control as events of the Yorktown campaign developed from a commander’s design or concept into an ongoing operation and the siege of Yorktown from September through November of 1781. This arrangement continued the parallel command structure described in Figure 1, with national command lines and coordination between senior national commanders. The key commanders, Washington, Rochambeau, De Grasse and De Barras continued to exercise unity of effort and mutual trust as they worked through the details of the operation. This structure worked for the Franco-Americans during the Yorktown campaign because of the common view of the mission and their ability to compromise, minimize friction and work toward a common campaign end state. The trust established between the military commanders, Washington, Rochambeau, De Grasse and De Barrras directly contributed to success in carrying out the multitude of tasks ultimately assigned to their subordinates.

This structure remained in place through the end of the siege and the surrender of Cornwallis. The solid lines depict command while the dotted lines depict coordination. Not depicted on the graphic are the state militia forces, upon which Washington relied heavily to augment Continental forces during the campaign. Virginia militia forces at Yorktown were under the command of the Virginia governor, Thomas Nelson. Nelson assumed the governorship of during the military crisis of 1781 because he was an experienced militia commander. Nelson’s Virginia militia operated on both the Yorktown side of the peninsula and in Gloucester on the Middle Peninsula supporting the Franco-American forces.

Nathaniel Greene’s southern forces continued to actively campaign in the Carolinas and Georgia. After the siege, Washington reinforced Greene with Pennsylvania, Virginia and Maryland units and returned the New York, New Jersey and New England troops to the Hudson River Valley to maintain watch over the British in New York. After the siege, Rochambeau’s French forces spent the winter in Virginia and garrisoned posts between West Point on the York River and Hampton at the entrance to the James River. Washington continued to maintain notional command of the French land forces under Rochambeau in North America. In reality, because the French forces occupied Virginia, Rochambeau’s command was geographically located in General Greene’s southern district. Therefore command was exercised by consent of Rochambeau as empowered by the French Government as previously described.[10]

The command and control arrangements described above supported the commander’s design and concept of operations and contributed significantly to an Allied victory, helping to end of the American Revolution as a military conflict. They reflect concepts clearly defined in contemporary U.S. joint military doctrine that evolved based on these and subsequent experiences that were later written into the law and incorporated into joint doctrine to institutionalize them. These successful command and control experiences of the Allies during the Yorktown campaign also anticipated and facilitated follow-on operations. De Grasse immediately returned to the Caribbean with his fleet where he engaged British naval forces. After wintering in Virginia, Rochambeau marched his troops back to New England during the summer of 1782 and embarked them for France. The outcomes of the Yorktown campaign and follow-on actions met the policy and strategy goals of the French government, while at the same time facilitating American policy and strategy. Effective command and control arrangements facilitated all of these successful actions.

[1] William B. Willcox, Portrait of a General (New York: Alferd A. Knopf, 1964), 272.

[2] Letter, Washington to Greene, June 1, 1781, in Henry P. Johnson, The Yorktown Campaign and the Surrender of Cornwallis, 1781 (Eastern National Park & Monument Association, 1975), 76-7n.

[3] Joint Chiefs of Staff, “Appendix L: Joint Chiefs of Staff Directive Unified Command for U.S. Joint Operations 20 April 1943 (JCS 263/2/D),” in Louis Morton, The United States Army in World War II, The War in the Pacific: Strategy and Command the First Two Years, 642-643 (Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1962). During World War II, U.S. forces formally documented the basic joint structure that informed current command and control practices. The National Security Act of 1947 and the Goldwater-Nichols Act of 1986 formally implemented the current system. These laws first created, then strengthened, the authority of the Secretary of Defense and developed a clear line of command and control of United States forces from the President of the United States through the Secretary of Defense to the unified and specified commanders that employ the forces. The military services, through the service chiefs, retain the responsibility to man, train and equip military forces, but joint force commanders employ the force. Also see: United States Congress, Goldwater-Nichols Act, The Department of Defense Reorganization Act of 1986, Pub.L. 99–43 (Washington, DC, 1986).

[4] Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, Joint Publication 1-02: Department of Defense Dictionary of Military and Associated Terms, February 15, 2016 (Washington, DC: Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, 2016), http://www.dtic.mil/doctrine/dod_dictionary/, accessed April 30, 2016. Joint operations involve forces from two or more service departments and multinational operations involve forces from two or more nations in a coalition or alliance.

[5] Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, Joint Publication 3-16: Multinational Operations (Washington, DC: Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, 2013). Chapter II addresses various forms of multinational command and coordination structures.

[6] Louis R. Gottschalk, Lafayette and the Close of the American Revolution (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1942), 96-97.

[7] Chairman, Joint Publication 1-02. Unity of command involves all forces under the command of one single commander.

[8] Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, Joint Publication 1: Doctrine for the Armed Forces of the United States (Washington, DC: Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, 2013) V-14 to V-17. Trust and mission command, involving trust as a key component, are two of the tenets of command and control.

[9] Chairman, Joint Publication 1-02. Unity of effort involves coordination and cooperation toward common objectives or purposes. Unity of effort is also discussed extensively in multiple chapters in Joint Publication 1.

[10] Gottschalk, Lafayette and the Close of the American Revolution, 96-97.

One thought on “Command and Control During the Yorktown Campaign”

I really enjoyed your article. You were very effective in describing coalition warfare to those that have not been exposed to it at the operational level of war (I was previously a CGSOC faculty).

Another good reason to visit and read this wonderful website.