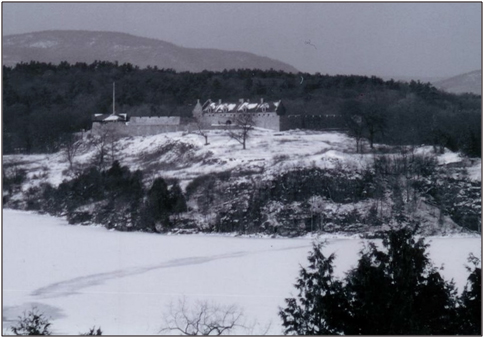

From the beginning, the American army knew south-facing Fort Ticonderoga did little to protect against an attack coming up Lake Champlain from British-controlled Canada.[1] To address the problem, they decided to fortify the north-facing peninsula, called East Point or Rattlesnake Hill, that poked out into the lake across from Ticonderoga. During the summer of 1776, thousands of men began working on clearing and developing the forested hill, renamed Mount Independence in July. In the late fall most of the troops went home leaving around 2,500 men to garrison both the Mount and Ticonderoga. We have all read stories of the suffering the army went through at Valley Forge but few know of the challenges winter presented to the men 300 miles farther north on Lake Champlain.

Today, instruments like thermometers and barometers are common place and detailed weather history and reasonable forecasts are easily accessible. Most eighteenth century people never saw such tools and finding precise weather information is rare even for developed areas. There is, however, some data available on the winter of 1776-1777 at Mount Independence and Ticonderoga. Sources occasionally note how pleasant or cold a day happened to be, that it rained or snowed, that the lake froze or some such occurrence. They are not regular and do not give specific details but combining comments from several sources affords a reasonable overview of the weather. Using the same sources we can also form an impression of how it affected the men stationed there.

The Weather

Although the winter of 1776-1777 can be shown to have been moderate,[2] it seems to have begun earlier than winters typically do today.[3] On October 20, Governor-General Sir Guy Carleton, camped at Crown Point following his recent victory over the American fleet at Valcour Island, noted “the severe season approaching very fast.”[4] The Americans just south of him made the same observation. The first flakes of snow fell during the night of October 12 and daytime snow squalls arrived on November 2 with more significant snow twelve days later.[5] By November 17, ice had begun to form on the lake and the mountains to the north had become “white with snow.”[6] Winter had arrived.

The cold continued unabated. The early part of December also proved wet “so that it froze as fast as it fell, which caused it to be very slippery, and with the darkness of the night made it bad.” By the second week of the month, much of the lake had frozen over except where other waterways entered. The constant flow of water from the LaChute River below the walls of Ticonderoga kept the narrows between the Mount and Ticonderoga open longer than the still waters. Even the open areas soon froze over with the ice on the entire lake being thick by the end of December. Although cold, the soldiers could be thankful that they had minimal snow to deal with. That changed two days after Christmas when the first major storm deposited knee-deep snow.[7]

The new year brought continued stormy and cold weather. Ebenezer Elmer, a lieutenant in the Second New Jersey Regiment, described it as “piercing cold weather … The sun even in the most pleasantest days thaws but very little.” It continued to snow off and on for most of the month with heavy snow on January 16.[8] Temperatures warmed when the “January thaw” arrived a week later but it also brought rain.[9] After the short respite, the weather turned cold again. The rain-soaked snow developed a thick, hard crust and ice covered the bare ground and the snow packed by human traffic.

The weather began to change in February, however. The early part of the month brought with it a period of clear, pleasant weather but the air still had a bite to it.[10] Thankfully, cold, clear air tends to be dry which results in little snow. By the middle of the month, the severe cold had ended but, with warmer air being better at carrying moisture, the likelihood of snow increased. Indeed, February 24 featured a “very great snowstorm.”[11]

With warmer, sunnier days in early March, the ice and snow began to melt quickly. By March 10, the ice on the lake had begun to fail and, just four days later, engineer Jeduthan Baldwin wrote that he found “the Ice very Roten.”[12] A cold spell returned for the last week of March but did not last as a warm, south wind came up on the last day of the month. Although April featured some snowy, wet days and the snow would linger in sheltered places for some time, the warm weather spelled the end of winter. The lake finally became completely clear in the latter part of April.[13]

Clothing

The men on Lake Champlain suffered the poorest of two worlds: not only did they experience distressing weather, they also had problems with supplies. For one, the nascent state and national governments did not have much money with which to purchase items nor an effective supply system to distribute those goods they did acquire. To make matters worse, Mount Independence and Ticonderoga existed on the frontier of the colonies with long distances and poor transportation routes between the posts and their sources of supply. Even if those conditions could be overcome, Washington and the main army around New York attracted most of the already limited supplies available. The northern army had to make do with what they could get.

The most obvious protection from foul weather is clothing. Although plans called for the men to receive a yearly allotment from the army, they seldom received much of it. Commissary George Measam told Horatio Gates that, “I have not been able to put the Troops in any tolerable Order with respect to Clothing, to enable them to do the Fatigue of a Soldier in these frozen Regions. … I have not received any Kind of Clothing from Albany, or any other Place.”[14] Lieutenant Elmer wrote on January 15 that he tried to get shoes for his men but could not.[15] The poor conditions remained in the memory of Asa Hale, a soldier in Benjamin Whitcomb’s Independent Corps of Rangers: “Those soldiers who were in Majr. Whitcomb’s department and Capt Lees the years previous [1776-7] were very destitute of clothing, some were reduced to nothing but one shirt and perhaps an old ragged blanket. One Soldier was sentenced to be whipped for refusing to do Duty in this Situation But was pardoned.”[16] Whitcomb himself wrote of the poor supplies: “The Blankets were all Rotten, the Whole Number unequal to the Value of 3 good Blankets, the Shoes poor leather and very Deceitfully made, and the Rest very much proportional to the Shoes & Blankets; and now at this approach of Winter, the Men are again Destitute of Cloathing, especially Shoes & Blankets. That is to say they are unfitt for Service.”[17]

Shelter

The army made use of three basic forms of living quarters—tents, huts, and barracks. The lack of sufficient barracks and huts forced a portion of the garrison to live in tents for some time. To help make life in the canvas shelters more comfortable, the men made use of the saw mill on the LaChute River. Over the tent, they erected a shell of boards and bark-covered slabs cut off the outside of the logs, then stuffed a layer of insulating grass and leaves between the covering and the tent. At least some tents had wood floors and probably all had small fireplaces and chimneys. At least a few men put their tents on top of two or three courses of logs or boards allowing for a more commodious living space.[18] Still others built wedge-shaped shelters like tents but made solely of wood.[19]

Huts provided shelter for most men and came in two forms—log or board. On forested Mount Independence, the men commonly built their huts out of logs gathered in clearing the encampment. The structures sat directly on the ground or on a minimal stone foundation.[20] Conditions differed on the Ticonderoga side. With continuous occupation since the fort’s construction twenty years earlier, the land surrounding it had already been cleared. Gathering logs for hundreds of huts would be a task beyond the capabilities of the available men and draft animals. The saw mill, however, sat much closer to the uncleared forest so the men dragged the logs to the mill and used beams and boards to build their huts.[21] Numerous depressions up to two feet deep have been found at Ticonderoga indicating that at least some of the huts had dug foundations.[22] The reason for this is not known but it might have been an attempt to get below the frost line or to utilize the ground as a heat sink. Once warmed up, it will retain heat for an extended period.

Whether log or board, the huts had several similarities. The sizes varied but most had sides ten to fifteen feet long and lacked windows.[23] One end wall had a door and the other a fireplace and chimney. The side walls of many huts likely featured bunks but some men surely just slept on the floor which could have been dirt, bark, or board. Orders called for shingled roofs but shortages of shingles and nails resulted in many huts being covered with bark, slab wood, or boards. Whatever the roofing material, it leaked. Benjamin Beal’s diary for a one-week span hints at the frustration at trying to keep dry: “We Went on to finish our huts it rains we covered them with bark they leaked and we got wet … We Went to finish our house but it rained We got our house so as it did not leak much … rain last night our huts leaked”[24] There is no indication that they ever stopped the leaks.

In spite of the leaks, Beal at least had some decent shelter. One diarist, Zephaniah Shepardson, recounts being sick in the hospital for a few days and returning to his hut to find that the other men had taken on another person in his place. With nowhere to live, Shepardson laid a piece of bark on the ground between two huts with another piece overhead.[25] Although this particular incident did not take place in the winter, with large numbers of sick men in the hospitals during the winter, similar situations may have arisen.

Our modern minds envision huts as poor shelter but they may actually have been rather comfortable. Valley Forge National Historical Park conducted an experiment wherein some rangers lived in one of their reconstructed log huts for several days. Gauges installed at various places around the inside and outside of the hut measured weather conditions throughout the period. After two or three days during which the fire thawed the hut and ground, the conditions inside the hut remained quite comfortable even with winter weather outside.[26]

The army also had barracks. On the Ticonderoga side, 400 men had use of the stone barracks within the fort. In November, engineer Jeduthan Baldwin began construction of post and beam barracks for 800 men as part of the Star Fort on the high ground on Mount Independence.[27] Unfortunately, these structures would remain unfinished until well into the winter. Assigned to one of the new barracks in December, Elmer found his building “very open, without any doors, chamber floor, or anything except just covered and partitioned off.” Nevertheless, he made the best of it: “I filled up our fire-place with clay for a hearth and other things about the house, in order to be something more comfortable.” In spite of his efforts, “the night was so excessively cold, and room so open, I could not sleep—indeed suffered most intolerably all night; learning some thing farther of the fatigues of a soldier’s life.”[28] Fifty stoves for the barracks had been requested but no documentation of their delivery or use has been found.[29] In like manner, Baldwin wanted glass for windows but it remained “much wanted.”[30]

Fatigue

Winter did not lessen the necessary work—called fatigue duties. Barracks and other buildings needed to be completed, the picket wall (logs several feet high placed a couple inches apart in a trench) around the fort on Mount Independence had to be installed, platforms and walls for artillery emplacements and breastworks for infantry needed to be constructed along with any number of other labors necessary to make the complex livable and defensible. Digging in ground frozen to a depth of at least two or three feet would have been extremely difficult but in mid-February, a party of men from Elmer’s regiment spent a few days installing abbatis. These are posts or small trees and branches with the ends facing the enemy sharpened and the other end sunk into the ground.[31] On rare occasions, the weather proved so bad that the officers excused the men from the work. Oddly enough, the spring day of March 29, 1777, proved to be one such day, “so Cold that we could not work at the Bridge [between the two posts].”[32]

Whether working on the bridge, barracks, or fortifications, people sweat—even in cold weather. Any moisture absorbed by the clothing will chill the body and even freeze. In an extreme case, on December 2, a party took some flatboats up the LaChute to gather boards at the saw mill. Once loaded, they found the flatboats had settled onto the river bottom and would not move. Unable to get them off the snags using their poles and oars, some of the men went into the chest-deep water—water with a temperature probably in the low forties Fahrenheit. After wrestling the boats free and pulling them some distance down the river, the men climbed back on their boats and their clothes promptly froze. They finally reached Mount Independence around 8:00 p.m. when the men “went home in a frozen condition.”[33] Whether any men died as a result of that experience is not known but the loss of body heat (hypothermia) resulting from such activities can easily prove fatal.

Mounting Guard and Scouting

Guard duty is critical at a post on the edge of no-man’s land and those men camped on the Mount did not get excused from such duty on the Ticonderoga side. That meant that not only did they have to spend their time exposed to the winter weather at the guard posts, they also had to form in their camp on the Mount, march off the Mount, row across the lake in boats or march across the quarter-mile-long bridge or on the ice to the Ticonderoga side, and then to their posts.[34] The process would likely have taken around an hour in each direction, adding two hours to the time the men spent out in the winter weather. In an effort to reduce the impact, the guards did get relieved after one hour instead of the two or more usually spent on guard.[35]

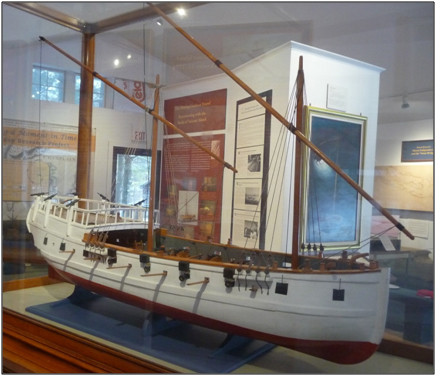

In an unusual twist for inland fortifications, some of the men mounted guard on ships moored at Ticonderoga. Although locked in the ice, the boats needed to be guarded in the event an enemy raiding party tried to burn them. Unlike the guards around the fortifications, those on the boats lived aboard them for a period of a couple weeks before being relieved. Also unlike the men on normal guard duty, the men on the ships practiced using the cannons aboard the ships.[36]

Being on the front lines also meant scouting for signs of the enemy. In his orders turning over command of Mount Independence and Ticonderoga to Colonel Anthony Wayne, General Philip Schuyler told him, “you will continually keep scouting parties on the Lake, as long as the Season will permit it to be navigated, and when that is no longer passable practicable parties must be kept out on both Sides of the Lake, to give the earliest Intelligence of the approach of an Enemy.”[37] These missions ranged from short one-day routes to multi-day movements far down the lake and the men could be drawn from any units of the garrison. Parties also went out in pursuit of enemy scouts and raiders.[38] Winter may have slowed down the war but it did not cause it to cease entirely.

Drill

Judging by the number of comments found in diaries, drilling caused the most problems for the men. Fatigue duty may have been hard, but at least the constant movement helped keep them warm. When drilling, the men stood with little movement for most of the time allowing the cold to penetrate to the bone. Because of constantly fighting the cold, some saw little value in drilling: “the weather was so cold, they could not exercise with that life which they usually did in warmer weather.”[39]

The men often spent hours drilling on the ice of the lake exposed not only to the cold but to the wind that regularly blows across the open ice. Occasionally, they received a bit of rum or other spirits but they always came off the ice suffering from the cold: “when being dismissed I repaired on board [the ship Gates] much troubled with the rheumatism proceeding from standing so long in the cold.”[40] The soldiers drilled on Christmas day “and the men almost perished.”[41]

Life and Death

Serving in a remote location like Mount Independence and Ticonderoga could not have had much appeal and being there in the winter must have been that much worse. Along with the cold and snow, shortages of supplies, garrisoning a dilapidated fort, and trying to repair old positions or construct new ones, various illnesses ran through all the regiments. In cold weather, the body’s need to maintain its warmth expends energy that would otherwise be used to fight off diseases. On four separate days over the span of two weeks, Jonathan Burton noted more than two dozen men in his company sick.[42] Ebenezer Elmer noted for December 10, “We have now above 100 sick belonging to this regiment. The most frequent complaint is the camp dysentery, and has been rife ever since we came upon this ground, though it now begins to grow less frequent as the weather grows cold and severe—and more inflammatory disorders, of a very complex nature, come in its place.”[43] On December 20, Elmer noted that his regiment remained “very sickly” and that “[s]carcely a day passes but some one dies out of it.”[44] A muster roll for his company dated January 1, 1777, listed as sick twenty-five out of about forty men—including the doctor.[45]

The list of sick men in the garrison continued to grow as winter deepened. Wayne wrote to Gates about it and one can almost feel him chocking up as he penned his note: “We shall be hard set to get the sick away; our hospital, or rather house of carnage, beggars all description, and shocks humanity to visit. The cause is obvious: no medicine or regimen on the ground suitable for the sick; no beds or straw to lay on; no covering to keep them warm, other than their own thin wretched clothing. We can’t send them to Fort George as usual, the hospital being removed from thence to Albany, and the weather is so intensly cold that before they would reach there they would perish.”[46] The trip meant the sick men would spend several days exposed to the winter weather in carriages, wagons, or sleighs. Even healthy men would have been pressed to come through that trip unscathed. Illness became enough of a problem that during the January thaw, Wayne finally sent many of the sick to Albany.[47]

The number of sick certainly increased as a result of malnutrition. Not only did the men receive limited rations for days or weeks at a time, they received the same things day after day and the body needs variety to remain healthy. Jeduthan Baldwin noted that several of his men could not work because of receiving “only 12 ouz. of pork & 1½ lb of flower pr Day.”[48] Working on the bridge, in particular, must have been very difficult when both cold and hungry. Many decades later, James Rankins, Jr., told the clerk filling out his pension application, “but of one fact he is very certain; it was a cold job, and in the prosecution of it he endured great fatigue, & suffered from hunger & want of Cloathing.”[49]

Along with sickness, the cold snowy weather brought its own set of challenges: “This Day, three men are returned frost-bit.”[50] A few days later proved to be a “very snowy day. … The night proved equally stormy with the day, so that two men coming from Skenesborough to this place, suffered greatly, one perished 5 miles off from here, and the other but just escaped.”[51] Even the officers suffered from the cold in spite of their better living conditions. Colonel Wayne wrote to General Gates that even after spending three hours before the fire, “I was not half thawed until I put one Bottle of wine under my Sword belt at Dinner—I have been toasting you all but can’t toast myself—for by the time that one side is warm the other is froze.”[52]

Scores did perish as a result of the weather. For two months, Jonathan Burton kept an account of the men from the New Hampshire regiments who died. Once the count reached around two dozen, he seems to have stopped making note of the deaths.[53] Either the news no longer passed through the ranks or he just stopped making note. In either case, like most veteran soldiers, the New Hampshire men must have become hardened to death.

Burying the dead became a problem once the ground froze. By mid-winter, the frost in the ground made the pick-axe rather than the shovel the preferred tool for digging. The challenge of burying one’s brothers-in-arms can be seen in an incident that happened to Ebenezer Elmer. Two men from his company perished and Elmer with some other men dug the graves for the burial. They went back to get the bodies and upon returning to the graves, found some Pennsylvania men burying two of their compatriots in them. After some long discussion—probably heated at times—the Pennsylvania men disinterred their comrades and Elmer and his friends completed their melancholy task.[54]

Diversions

Soldiers being soldiers, the men at Mount Independence and Ticonderoga did find ways to enjoy themselves during the winter. Some went sledding or skating, and snowball fights did break out—some certainly in fun but others probably with varying degrees of antagonism. In spite of orders against them, “Cards and drinking are the diversions which the whole garrison are daily employed at.”[55]

Valley Forge

There is no question that the weather at Valley Forge presented its challenges to the men and women who camped there.[56] This article is not intended to denigrate the hardships they faced but, rather, to point out that the army camped in the Champlain valley had it much rougher. While the 1776-1777 winter in the north cannot be directly compared with the 1777-1778 winter at Valley Forge, there is a way to accomplish the next best thing—a comparison of the weather in the two areas for the winter of 1776-1777. Thomas Coombe and Reverend Henry Melchior Muhlenberg lived within a few miles of Valley Forge and kept detailed weather records. A comparison can be achieved using their information on the winter of 1776-1777.

Washington’s army marched into Valley Forge when the weather began to turn wintery—on December 19, 1777. By that date in 1776, the northern army had been experiencing cold weather for two months, snow covered the ground, and most of Lake Champlain had frozen over. While the precise temperatures in the Champlain valley during the winter of 1776-1777 will never be known, it must have consistently been well below freezing for the lake to ice over. During the same period the northern army experienced only one period of thawing. In contrast, the temperature in the area of Valley Forge never fell below six degrees Fahrenheit and frequent thaws occurred each lasting from three to six days.[57]

The area around Valley Forge also did not suffer the amount of snow that the northern army experienced. Reports of the first snow by Coombe and Muhlenberg appear five weeks after that on Lake Champlain. Both sites appear to have twice been hit by the same snow storm with both producing several inches more to the north than at Valley Forge. The deepest snow on the ground at Valley Forge lasted three days as heavy rains beginning on February 8 washed much of it away. By the end of February, most of the ground had become bare.[58] The snow in the north lasted until well into April.

The Valley Forge region did have one problem the northern army did not: the regular thaws produced muddy ground which, if rutted, becomes appalling, upsetting, and often dangerous to move over. The remaining snow soaks up the water and, when it freezes again, develops a grainy crust that is difficult to move over. At worst, the waterlogged snow becomes a sheet of ice.

Unrelated to weather, Washington’s army had an advantage in their location—they had a large developed area within easy reach. Joseph Plumb Martin made note of the advantage: “We fared much better than I had ever done in the army before, or ever did afterwards. … When we were in the country we were pretty sure to fare well, for the inhabitants were remarkably kind to us.”[59] In contrast, the soldiers in the Champlain valley did not have many inhabitants from whom to garner supplies and clothing. They had to rely on supplies reaching them from long distances but, as mentioned above, that system did not prove reliable.

In a letter to Robert Morris penned at Ticonderoga in December, 1776, Joseph Wood wrote, “it’s now as cold as ever I felt in my life.”[60] This is a direct comparison between the weather in the north and the area around Valley Forge. Wood lived near Valley Forge and knew full well what winter in Pennsylvania felt like in relation to that at Mount Independence and Ticonderoga.

Conclusion

Modern technology has made our lives comfortable and, every day, advancements add to our ability to shelter ourselves from the weather. We pay a price for that comfort, however. Every step forward has done more to isolate us from nature to the point where many people have little concept of what experiencing bad weather—winter, in particular—feels like on a daily basis. Maybe we go out in the cold to brush snow off our car or shovel for a while but we quickly and easily retreat to a much warmer shelter. The men—and the women accompanying them—who dedicated themselves to fighting for their posterity had no such luxuries. Next time you go out in foul weather, stay out there for a while and think about those people and what they must have gone through. They deserve at least a few moments of consideration.

[1] Lakes George and Champlain flow north so moving south is coming up either lake.

[2] Marc Brier, “Tolerably Comfortable: A Field Trial of a Recreated Soldier Cabin at Valley Forge” (Valley Forge National Historical Park: 2004), 2.

[3] Climatologists view the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries as the latter stages of a “mini ice age” with a maximum beginning around 1770. See http://earthobservatory.nasa.gov/Glossary/?xref=Little%20Ice%20Age (accessed July 12, 2015).

[4] Guy Carleton to William Howe, October 20, 1776, in Naval Documents of the American Revolution, ed., William James Morgan (Washington, D.C.: Naval History Division, Department of the Navy, 1972), 6:1336.

[5] Benjamin Beal, Journal of Benjamin Beal (Worcester, MA: American Antiquarian Society), 18-19; Jeduthan Baldwin, Revolutionary Journal of Col. Jeduthan Baldwin, 1775-1778 (Bangor, ME: The DeBurian Society, 1906), 86; Jonathan Burton, The Diary and Orderly Book of Sergeant Jonathan Burton, ed. Isaac W. Hammond (Concord, NH:

n.p., 1885), 699-700.

[6] Burton, Diary and Orderly Book, 701.

[7] Ebenezer Elmer, “Journal Kept During An Expedition to Canada in 1776,” Proceedings of the New Jersey Historical Society 3 (1848), 47, 49-51. The LaChute is the outlet of Lake George and enters the southern arm of Lake Champlain at Ticonderoga.

[8] Elmer, “Journal,” 54-5.

[9] Baldwin, Revolutionary Journal, 91.

[10] Elmer, “Journal,” 91.

[11] Baldwin, Revolutionary Journal, 93.

[12] Ibid., 94-5

[13] Ibid., 96; Zephaniah Shepardson, A Narrative of Soldiery: The Journal of Zephaniah Shepardson, Guilford, Vermont, 1826. ed. Charles Butterfield (n.p.: 2000), 23.

[14] George Measam to Horatio Gates, December 15, 1776, in Peter Force, American Archives: Fifth Series (Washington, D.C.: 1853), 3:1237.

[15] Elmer, “Journal,” 55.

[16] Asa Hale, pension application, Revolutionary War Pension and Bounty-Land Warrant Application Files (Washington, D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, M804), 192.

[17] Benjamin Whitcomb to Henry Laurens, Papers of the Continental Congress (Washington, D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration) M247, roll 10:370.

[18] John Lacey, “Memoirs of Brigadier-General John Lacey of Pennsylvania (continued).” The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography 25 (1901): 346-7.

[19] Henry Sewell, quoted in “Board with Tents?,” The Fort Ticonderoga Blog, July 10, 2014, http://www.fortticonderoga.org/blog/board-with-tents/.

[20] Lewis Beebe, “Journal of Lewis Beebe, A Physician on the Campaign Against Canada, 1776,” The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography 59 (October 1935) 9, 29; David R. Starbuck, The Great Warpath (Hanover, NH: University Press of New England, 1999), 137.

[21] Lacey, “Memoirs,” 346-7. Col. Anthony Wayne, “Orderly Book,” November 23, 1776, quoted in “Lodging as the Nature of the Campaign Will Admit,” The Fort Ticonderoga Blog, November 30, 2014, http://www.fortticonderoga.org/blog/lodging-as-the-nature-of-the-campaign-will-admit/. Sewell, quoted in “Board with Tents?”

[22] “Lodging.”

[23] Ibid.; Starbuck, The Great Warpath, 137-8.

[24] Beal, Journal, 13-14.

[25] Shepardson, A Narrative of Soldiery. This incident is part of an illustration in an up-coming book on Mount Independence.

[26] Brier, “Tolerably Comfortable.”

[27] Donald Wickman, “Built With Spirit, Deserted in Darkness: The American Occupation of Mount Independence, 1776-1777” (Masters thes., University of Vermont, 1993), 51.

[28] Elmer, “Journal,” 49-50.

[29] Philip Schuyler to Anthony Wayne, November 23, 1776, quoted in “Keeping Ticonderoga Safe and Healthy During the Winter of 1776-1777,” The Fort Ticonderoga Blog, August 8, 2012, http://www.fortticonderoga.org/blog/new-details-emerge-about-life-at-ticonderoga-during-the-american-revolution/.

[30] Schuyler to Congressional Committee, November 6, 1776. During three years of work on Mount Independence, archaeologists found very little window glass (see Starbuck, The Great Warpath, 124-59). Aside from work in the area where Ticonderoga built the Mars Education Center, similar work has not been conducted.

[31] Elmer, “Journal,” 92-3

[32] Baldwin, Revolutionary Journal, 96. Crews built twenty-two pyramid-shaped caissons by laying courses of interlocking logs directly on the ice and placing rocks on platforms inside. They cut away the ice and continued to build until the caisson sat on the lake bottom with about three feet out of the water.

[33] Elmer, “Journal,” 47.

[34] Ibid., 50.

[35] Wayne, “Orderly Book,” 120.

[36] Elmer, “Journal,” 55-6.

[37] Schuyler to Wayne, November 23, 1776, quoted in “Keeping Ticonderoga Safe and Healthy.”

[38] Burton, Diary and Orderly Book, 695-700; Michael Barbieri, infamous Skulkers: Continental Rangers in Vermont During the American Revolution, master’s thesis (Norwich University, 1999), 132-140.

[39] Elmer, “Journal,” 48.

[40] Ibid., 55.

[41] Ibid., 51.

[42] Burton, Diary and Orderly Book, 694-5.

[43] Elmer, “Journal,” 48.

[44] Ibid., 51.

[45] Ibid., 91.

[46] Wayne, “Orderly Book,” 111-12, fn1.

[47] Elmer, “Journal,” 55.

[48] Baldwin, Revolutionary Journal, 60-1.

[49] James Rankins, pension application, Revolutionary War Pension and Bounty-Land Warrant Application Files (Washington, D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, M804), 19.

[50] Measam to Gates, American Archives, 3:1237..

[51] Elmer, “Journal,” 51.

[52] Charles J. Stille, Major-General Anthony Wayne and the Pennsylvania Line in the Continental Army (Philadelphia, PA: J.B. Lippincott, 1893). 45.

[53] Burton, Diary and Orderly Book, 694-699.

[54] Elmer, “Journal,” 93.

[55] Ibid., 51, 92.

[56] I am indebted to Dona McDermott, the archivist at Valley Forge National Historical Park, for her assistance in gathering information on the weather during the encampment at Valley Forge. Along with providing me some basic information, she directed me to more detailed sources and gave me permission to use the publication concerning the hut experiments.

[57] David M. Ludlum, Early American Winters (Boston: American Meteorological Society, 1966), 101-2. Ludlum’s detailed study includes considerable excerpts from the records of Coombe and Muhlenberg.

[58] Ibid., 101-2.

[59] Joseph Plumb Martin, Private Yankee Doodle (San Diego: Acorn Press, 1979), 81-3.

[60] Joseph Wood to Robert Morris, December 16, 1776, Fort Ticonderoga museum.

6 Comments

Mike, an excellent, and certainly interesting, article which provides a context useful in understanding the plight of the American soldier in the war. A college American History professor of mine use to emphasize the role and conditions of the “little man” in history as a key to understanding the larger events. This, it seems to me, is a valuable article in this regard.

A very well researched and cited article, Mike. The categories you’d divided the content into made it very pleasant to read and digest. And seemingly timely. The weather said you might be having an early start to winter this year in that area. Terrific information to appreciate what the average guy went through. Thank you.

Thoroughly enjoyed this article – always difficult to capture the practical side of soldiering, particularly aspects which we have lost as we assume modern conveniences of construction and HVAC.

Having dug in Vermont and constructed similar huts there and elsewhere, some observations. First, digging in Vermont is not like digging at most other AWI sites. The ground is stony and often there’s a bedrock ledge visible or just a few feet down. Even with that, digging was essential to construction for a number of reasons:

1. They needed the dirt for post construction purposes, so obtaining it on site was labor effective (chinking and external banking).

2. Digging, and setting the wooden construction on the edge of the hole, meant that fewer log courses were required to reach the desired interior height. Thus, recessing the foundation into the ground reduced the required timber and also saved the labor required to fell, strip, and shape the timbers or boards and move it to the construction site.

3. After construction, the removed dirt would have been used as a component of the chinking material (wet soil and clay daubed between logs and boards to enhance the structure’s wind- and water-proofing). Loose soil also would have been shoveled against the exterior walls to provide a reverse slope that channeled water away from the structure. These exterior banks also acted as a form of insulation. If started early enough in the season, these banks would have had cut turf laid over them to reduce erosion. The closer together the huts were built, the higher these banks could have been made, even benefitting from additional soil brought in from elsewhere (perhaps obtained from water diversion ditches dug to carry water away from the site.

Although I’ve visited Ft Ti a number of times, I’m not familiar with the Ft Ti archeological studies and can’t say whether these attributes were detected on site. The “holes” you mentioned suggest they used soil as an essential component of construction, as do the scarcity of available resources and the harsh climate. Lack of these attributes would have magnified the soldier’s hardships.

Again, great article on an overlooked aspect of soldiering!

Excellent article Mike. It makes one shiver just reading! Certainly these soldiers were not “sunshine patriots” as coined by Thomas Paine.

The Continental Army winter camp at Jockey Hollow in 1779-80 was also a testament to patriotic fortitude and may have been more brutal than Valley Forge. However, nothing compares to the winters in Vermont!

Thank you for the kind comments, gentlemen. In particular, I am glad to hear that some felt cold reading the article. That effect played a role in my writing process. Historians spent two centuries building the American myth by concentrating on great events and putting great men up on pedestals but the “LIP” (local indigenous population) saw little attention. It’s only in the last three or four decades that they are getting the deserved attention. I try to add to their story.

Regarding Jim’s comments about the dug hut foundations at Ticonderoga, I am unaware of ANY professional archaeological work being done on them. I am sure such work has been discussed but the site has been going through a restructuring period which, I’m sure, has necessitated concentrating on the more visible aspects of their presentation. Personally, I would love to spend time exploring what’s under the leaf litter that has filled those holes over the centuries. Such work would add considerably to the knowledge of the northern theater and, from my selfish perspective, would be a nice addition to my experiences working on the above-ground huts on Mt. Independence.

Lastly, the winter of 1779-80 is pretty much universally accepted as having been a severe one so the army camped at Jockey Hollow those months certainly suffered more than the previous winters. Of course, by that time most of Lake Champlain had become a no-man’s-land with no large numbers of troops in the valley.

Thanks for this excellent article. When reading Lt. Elmer’s journal I was struck by the line “…the men died so fast for some time that the living grew quite wearied in digging graves for the dead in this rocky, frozen ground…”. My ancestor spent winter with the 3rd New Jersey at both MI and at Valley Forge. Captain Joseph Bloomfield, in his journal, doesn’t really talk about the conditions, but he was sick most of the time he was there and left on Christmas day.

It all makes me cold thinking about it