Isaac Barré was born in Dublin, Ireland, in 1726. He was educated at Trinity College and following graduation in 1745 enrolled at the Inns of Court. Within a year he lost interest in the law and decided to enter the military. He served as an infantry officer, becoming a captain in the 32nd Regiment of Foot in 1758 and earning an appointment as adjutant-general on the staff of Gen. James Wolfe on that officer’s expedition to America.

Barré was there when General James Wolfe was fatally shot at the Battle of Quebec in 1759. In the same battle, Barré received a bullet wound to his right cheek that distorted his appearance and caused blindness in his right eye. He wrote several letters to Prime Minister William Pitt asking for promotion, but his request was denied. Barré seemed aware that his chances of promotion had been reduced with the death of Wolfe. In his first letter to Pitt, dated April 28, 1760, he wrote, “I am apprehensive that my pretensions to military advancement are to be buried with my only protector and friend.”[1] He remained in North America with Gen. Jeffery Amherst until October, when he returned to England

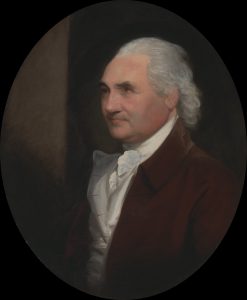

On December 5, 1761, with the help of Lord Bute and the Earl Shelburne, Isaac Barré was elected to Parliament. Horace Walpole left us a description what he heard and saw as he entered the House of Commons five days later, “My ear was struck with sounds I had little been accustomed to of late, virulent abuse on the last reign, and from a voice unknown to me. I turned, and saw a face equally new; a black, robust man, of a military figure, rather hard-favoured than young, with a peculiar distortion on one side of his face, which it seems was owing to a bullet lodged loosely in his cheek, and which gave a savage glare to one eye. “What I less expected from his appearance was very classic and eloquent diction.”[2]

Shortly after taking his seat in the House of Commons, Barré gained notice when in a speech he attacked William Pitt. He did this at Bute and Shelburne’s encouragement, for both strongly disagreed with Pitt’s policies towards Spain, and because Barré had not forgotten Pitt’s refusal to grant his promotion. In 1763 after Lord Bute became Prime Minister, Barré was awarded the rank of Lieutenant Colonel, Adjutant-General to the British Army and Governor of Stirling Castle. His reputation as a speaker increased with the passing of each year. In 1764, he, Shelburne, and Pitt resolved their differences and formed an alliance to oppose the ministry’s treatment of John Wilkes.

Opposing the Stamp act

The Stamp Act was a direct tax on the colonies. It required all printed materials be produced on paper from London bearing an embossed revenue stamp. It was created to pay for the cost of British troops stationed in North America. On February 6, 1765, Barré cautioned members of the House of Commons regarding passage of the Stamp Act:

We are working in the dark, and the less we do the better. Power and right; caution to be exercised lest the power be abused, the right subverted, and 2 million of unrepresented people mistreated and in their own opinion [made] slaves. There are gentlemen in this House from the West Indies, but there are very few who know the circumstances of North America … The tax intended is odious to all your colonies and they tremble at it … He [Townshend] thinks part of the regulation passed last year very wise in preventing them from getting the commodities of foreign countries. We know not however the real effect of this … We are the mother country, let us be cautious not to get the name of stepmother.

Charles Townshend recognized Barré’s points, and then stated “And now will these Americans, children planted by our care, nourished up by our indulgence until they are grown to a degree of strength & opulence, and protected by our arms, will they grudge to contribute their mite to relieve us from the heavy weight of that burden which we lie under?”

Isaac Barré immediately responded,

They planted by your care? No! Your oppressions planted them in America. They fled from your tyranny to a then uncultivated and unhospitable country ¾ where they exposed themselves to almost all the hardships to which human nature is liable, and among others to the cruelties of a savage foe, the most subtle and I take upon me to say the most formidable of any people upon the face of God’s Earth. And yet, actuated by the principles of true English liberty, they met all these hardships with pleasure, compared with those they suffered in their own country, from the hands of those who should have been their friends.

They nourished up by your indulgence? They grew by your neglect of them: as soon as you began to care about them, that care was exercised in sending persons to rule over them, in one department and another, who were perhaps the deputies of deputies to some member of this House ¾ sent to spy out their liberty, to misrepresent their actions and to prey upon them; men whose behavior on many occasions has caused the blood of those Sons of Liberty to recoil within them; men promoted to the highest seats of justice, some, who to my knowledge were glad by going to a foreign country to escape being brought to the bar of a court of justice in their own.

They protected by your arms? They have nobly taken up arms in your defense, have exerted a valour amidst their constant and laborious industry for the defense of a country, whose frontier, while drenched in blood, its interior parts have yielded all its little savings to your emolument. And believe me, remember I this day told you so, that same spirit of freedom which actuated that people at first, will accompany them still. But prudence forbids me to explain myself further. God knows I do not at this time speak from motives of party heat, what I deliver are the genuine sentiments of my heart, however superior to me in general knowledge and experience the reputable body of this House may be, yet I claim to know more of America than most of you, having seen and been conversant in that country. The people I believe are as truly loyal as any subjects the King has, but a people jealous of their liberties and who will vindicate them, if ever they should be violated, but the subject is too delicate and I will say no more.[3]

In this momentous monologue, Barré called the British colonists in America the “Sons of Liberty,” a phrase that was quickly adopted in the New England colonies and would forever be connected with opposition to the Stamp Act.

Opposing the Declaratory Act

The Stamp Act was repealed, but it was soon followed by the passage of the Declaratory Act. William Pitt believed that the Stamp Act’s repeal represented a significant concession on the part of Parliament and that the only way to secure the repeal was to counter-balance it with an Act asserting Parliament’s authority.

On February 3, 1766, almost one year to the date of his most famous speech, Barré spoke against the Declaratory Act. He moved that the words at the end of the resolution “in all cases whatsoever” be stricken. He stated, “Let their [America’s] origin be what it will, they are now become [a] great Commonwealth. It is clear that no man has the right to tax [another man’s] money without his own consent or by his representative.” Barré then held up a picture of America and said “larger than Europe and perhaps in the whole containing more inhabitants, peopled from this little island. Can any sight or any prospect be more flattering to humanity or more glorious and more likely to immortalise it in the annals of fame?” he asked. Regarding American representation in Parliament, he responded, “The idea of a representative from that country is dangerous, absurd and impracticable. They will grow more numerous than we are, and then how inconvenient and dangerous would it be to have representatives of 7 millions there meet the representatives of 7 millions here.” He then warned:

If you do mean to lay internal taxes, act prudently and draw the sword immediately. The ulcer will remain, and they will expect another Stamp Act the next year. If you enforce the Act, you must draw the sword. You will force them to submit, but the trade will be forced to submit like wise . . . All colonies have their date of independence . . . The wisdom or folly of our conduct may make it the sooner or later. If we act injudiciously, this point may be reached in the life of many of the members of this House.[4]

Opposing the Townsend Acts

One year after the repeal of the Stamp Act, a series of acts called the Townshend Acts were created to pay for the salaries of colonial royal governors and judges as well as for better enforcing compliance with the trade regulations. On January 26, 1769, in reference to the Townshend Acts, Barré stated categorically that the American colonists

will not submit to any law imposed upon them for the purposes of revenue … In such a situation, she would serve only as a monument of your folly. For my part, the America I wish to see is America increasing and prosperous, raising her head in graceful dignity, with freedom and firmness asserting her rights at your bar, vindicating her liberties, pleading her services, and conscious of her merit. This is the America that will have courage to fight your battles, to sustain you when hard pushed by some prevailing force and by her industry will be able to consume your manufactures, support your trade, and pour wealth and splendor into your towns and cities. If we do not change our conduct towards her, America will be torn from our side. I repeat it, unless you repeal this law [the Townshend duties], you run the risk of losing America.[5]

On April 9, 1770, Parliament repealed all of the Townshend Acts but one – the tax on tea. This action would lead to the Boston Tea Party and further colonial protests.

On April 19, Barré questioned the continued existence of the tea tax:

This tax has been said to be not a fruitful one; I think it a very fruitful one, for it has produced riots and disturbances; it has been resisted, it has done its duty, let us dismiss it. I have been much quoted for requisitions; if you will make them with some address, they will comply. I have been also quoted for the olive branch; I say, you have let slip several millions in the East, and now look for a revenue from a pepper-corn in the West. This you will have to lay to your charge, that you will whet your swords in the bowels of your own subjects, and massacre many of your fellow-creatures, who do not know under what constitution of Government they live, by enforcing this tax.[6]

Opposing the Boston Port Act

Following the destruction of tea in Boston Harbor in December 1773, a series of acts that were created to punish the citizens of Boston for their rebellious activities. The first, the Boston Port Act, was passed on March 25, 1774. It ordered the port of Boston closed until the East India Company received full payment for all of the tea that had been destroyed and the crown received full payment for all of the lost tax revenue. On March 14, 1774, Barré cast his vote in support of the Boston Port Bill, but stated, “I shall agree with the motion for an address as a mere matter of course, but not holding myself engaged to a syllable of its content.”[7]

On March 17, he “wished to see a unanimous vote in the onset of this business; that when Boston saw this measure was carried by such a consent, they would the more readily pay the sum of money to the East India Company; that he hoped, if they did, that the Crown would mitigate the rest of their punishment.”[8]

On March 23, Charles Van, a member of Parliament from the Welsh borough of Breccon, declared “the town of Boston ought to be knocked about the ears, and destroyed; Delenda est Carthago. You will never meet with the proper obedience to the laws of this country, until you have destroyed that nest of locusts.” The Latin phrase for “Carthage must be destroyed” was used by the Roman Republic towards her rival, the city of Carthage, in the Punic Wars of the second century BC. Barré challenged the phrase because historically it had a very definitive meaning: “I should not have risen … had it not been for those words. The Bill before you is the first vengeful step that you have taken … This Bill, I am afraid, draws in the fatal doctrine of submitting to taxation; it is also a doubt by this Bill, whether the port is to be restored to its full extent. Keep your hands out of the pockets of the Americans, and they will be obedient subjects.”[9]

Opposing the Impartial Administration Act

The second punitive act, the Impartial Administration of Justice in Massachusetts, was passed on May 20, 1774. It suspended the right of self-government and turned control of the colony over to the Royal Governor who now had the authority to send rebellious colonists to England for trial. On April 15, Barré had been the first to speak after Lord North presented the bill.

I must call you to witness that I have been hitherto silent, or acquiescing, to an unexpected degree of moderation, While your proceedings, severe as they were, had the least colour of foundation in justice, I desisted from opposing them; … but [this] proposition is so glaring, so unprecedented in any former proceedings of Parliament; so unwarranted by any delay, denial, or perversion of justice in America; so big with misery and oppression to that country, and with danger to this – that the first blush of it is sufficient to alarm and rouse me to opposition. It is proposed to stigmatize a whole People as persecutors of innocence, and men incapable of doing justice; yet you have not a single fact on which to ground that imputation. I expected the noble Lord would have supported this motion by producing instances of the officers of Government in America having been prosecuted with unremitting vengeance, and brought to cruel and dishonourable deaths, by the violence and injustice of American Juries … Captain Preston and the soldiers, who shed the blood of the People, were fairly tried, and fully acquitted. It was an American jury, a New England jury, a Boston jury which tried and acquitted them. Is this the return you make them … Alienate your Colonies, and you will subvert the foundation of your riches and your strength.” He challenged Lord North’s advisors, Edward Thurlow, the Attorney General and Alexander Wedderburn, the Solicitor General to: ”declare, if they can, that there is upon your table a single evidence of treason or rebellion in America. They know, there is not one, and yet are proceeding as if there were a thousand … In assenting to your late [Boston Port] Bill I resisted the violence of America, at the hazard of my popularity there. I now resist your phrenzy at the same risk here. [10]

On May 6, Barré warned the House that the colonists would not agree to anything they feared would place them in a state of slavery:

I think it criminal to sit still upon the final decision of this question, as I cannot, in any shape, approve of this measure. I think the persons whom you employ to execute your laws, might have been protected in the execution of their duty in a less exceptionable manner than [the] Bill proposes. Your Army, in that country, has the casting voice; and it is dangerous to put any more power into their hands … The People of America will receive these regulations as edicts from an arbitrary Government. The heaviest offence they have been guilty of is, that they have resisted that law which bears such an arbitrary cast … I do not apprehend the Americans will abandon their principles; for if they submit, they are slaves.[11]

Opposing the Better Regulation of Government Act

The third of the punitive acts, the Better Regulating of Government in Massachusetts, was passed on May 20, 1774. It revoked the charter of the colony of Massachusetts, dissolved the Provincial Assembly and forbid selectmen of any township or district to hold a meeting without the permission of the governor. On May 2, again Barré seemed to have had a prescient understanding of the impact of the act:

The question now before us is, whether we will choose to bring over the affections of all our Colonies by lenient measures, or to wage war with them? I shall content myself with stating —that when the Stamp Act was repealed, it produced quiet and ease … You sent over troops in 1768, and in 1770 you were obliged to recall them … All other Colonies behaved with nearly the same degree of resistance, and yet you point all your revenge at Boston alone; but I think you will very soon have the rest of Colonies on your back … You propose, by this Bill, to make the Council of Boston nearly similar to those of the other Royal Governments; have not the others behaved in as bad a manner as Boston … Let me ask again, what security the rest of the Colonies will have, that upon the least pretence of disobedience, you will not take away the Assembly from the next of them that is refractory? … I do not know of any precedent for this Bill — I think this Bill is, in every shape, to be condemned … and all the protection that you mean to give to the military, whilst in the execution of their duty, will serve but to make them odious. I would rather see General Gage invested with a power of pardon, than to have men brought over here to be tried … You are, by this Bill, at war with your Colonies … therefore, let me advise you to desist … In one House of Parliament, we have passed the “Rubicon,” in the other “Delenda est Carthago” … I see nothing in the present measures but inhumanity, injustice, and wickedness; and I fear that the hand of Heaven will fall down on this country with the same degree of vengeance.[12]

There is no record of Barré speaking during the brief debate on the renewal of the Quartering Act. Passed on June 2, it permitted the billeting of soldiers and officers in uninhabited houses and buildings if there were no barracks available.

Opposing the Quebec Act

The Quebec Act was not one of the four punitive acts that came to be known as the Coercive Acts, however it was passed shortly afterwards on June 22. The act provided for recognition of the French Civil Code in all but criminal matters, the free practice of Catholicism, and the extension of the province’s boundary as far west as the Mississippi River and as far south as the Ohio River. On May 26, Barré could not grasp why the Catholic Church was being granted such latitude:

The Bill was every way complete; that its clauses perfectly corresponded with its principle; and that taking them unitedly, they were the most flagrant attack on the constitution that had hitherto been attempted. … I cannot agree that there is any thing in the laws of England, in the trial by Jury, and the habeas corpus, that the Canadians would not very easily understand; and it is preposterous to suppose, that the superiority of good and just law, and freedom, should not be felt by People, because they had been used to arbitrary power. But why is the religion of France, as well as the law of France, to become the religion of all those People not Canadians, that pass out of one Colony into another? By this Act you establish the Roman Catholic religion where it never was established before … [13]

On May 31, Barré told his colleagues in the House that the Ministry will never divulge their full reasoning behind the Bill because if they did, it would not stand up to scrutiny.:

I think there will be very little difficulty in showing, that the proposition now made by the noble Lord [North] will be very far from answering the purpose of those who wish for full information on this subject. “[14] “The papers we now call for would give us that information … That satisfaction should be made [to] the House on these points nobody can doubt; for to tell us that we cannot have information for want of time to copy papers, is to tell us plainly that we are to proceed in the dark; it is and will be a deed of despotism, and therefore may well be linked with darkness … It is [an] exertion of arbitrary power, in which the less concern Parliament has, the better. Intelligence must be kept from us because it will not bear the light; if it was openly and fairly laid before you, it would condemn in the strongest and clearest manner the principles and the provisions of this Bill, all of which it would be found are equally unnecessary and pernicious.[15]

On June 8, 1774, Barré questioned Lord North’s honesty. He alleged the Bill had originated with the Lords, “who were the Romish Priests that would give his Majesty absolution for breaking his promise given by the Royal Proclamation, in 1763;” that they, in this Bill, “had done like all other Priests, not considered separately the crimes with which the Bill abounded, but had huddled them all up together, and, for dispatch, had determined to give absolution for the whole at once.’’ He said, he was certain, that after Lord North’s death and those of his followers people would say, as they did after the death of King Charles, “that by papers found in their closets [they appeared] to have died in the Roman Catholic belief.”[16]

Opposing the use of Foreign Troops

King George III signed a treaty with the Duke of Brunswick on January 9, 1776, with the Landgrave of Hesse-Cassel on January 15 and with the Hereditary Prince of Hesse-Cassel on February 5, permitting the British government to hire German troops to fight in the American colonies. On February 19, Lord North presented the treaties to the House of Commons.

Barré assured Lord North and Lord Barrington that America would never submit to be taxed even if “half of Germany were to be transported over the Atlantic to effect it.” He then reminded Lord Barrington “of the assurance he gave on a former occasion, that no foreign troops were meant to be employed. ” After Barrington denied giving such an assurance, Barré turned his attention toward Lord North and his ministers – telling them “they were not fit to conduct the affairs of a great nation, either in peace or war.” He said he “did not doubt but this sale of human blood would turn out as advantageous to the woollen manufactures of Brunswick and Hesse, in the clothing branch, as it was already likely to become lucrative to their respective Sovereigns.”[17] Not only were these treaties resolved in the affirmative but also the treaty with the Prince of Waldeck that would be signed on April 20.

On October 31, Barré expressed his concern about the state of England’s Navy. He believed that France and Spain posed a real threat. He recommended to the ministry “to make up matters with America … that we had in the last war 12,000 seamen from America, who would now, should France attack England, be fighting against us; that all the useful part of our navy was on the coasts of America … that unavoidable ruin hovered over this devoted country. Recall, therefore, your fleets and armies from America, and leave the brave colonists to the enjoyment of their liberty.”[18] His plea brought only laughter from the ministerial benches.

Epilogue

In 1783, the bullet that was lodged under Isaac Barre’s right eye caused him to go blind. In 1790 he resigned his seat in Parliament and retired to his home in the Mayfair district of London. On July 20, 1802, the hero to every American who knew his name died. His importance to Americans of the era lives on in the names of Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania, name for him and John Wilkes in , 1769 and Barre, Massachusetts, named for him in 1774.

Though name of Isaac Barré has been lost in the history of the American Revolution, his accomplishments were impressive. He was a lieutenant colonel and adjutant general before the age of thirty-three, a member of Parliament for close to forty years and a leading debater during most of them, the governor of Stirling Castle, the Vice-Treasurer of Ireland, the Treasurer of the Navy, Paymaster of the Army, Clerk of the Pells, and most importantly, while holding all of these offices, one of the most notable defenders of the American colonies in the House of Commons. The colonists knew of him as much as they knew of Edmund Burke or John Wilkes. Whether aligned with the Earl of Shelburne, Lord Chatham or Lord Rockingham, he defended the colonies against arbitrary bills and for that, America says Thank You!

1 William Stanhope Taylor and Captain John Henry Pringle, eds., Correspondence of William Pitt, Earl of Chatham (London: John Murray, 1838), 2:41-3.

2 Horace Walpole, Memoirs of the Reign of King George the Third, Denis Le Marchant, ed. (London: Richard Bentley, 1845), 1:109.

3 “Speech of Isaac Barré, Common Debates, February 6, 1765,” Parliamentary Diaries of Nathaniel Ryder, Peter David Garner Thomas, ed. (London: Royal Historical Society, 1969), 257; The Fitch Papers: Correspondence and Documents During Thomas Fitch’s Governorship of the Colony of Connecticut, 1754-1766, Albert Carlos Bates, ed. (New Haven: Connecticut Historical Society, 1918), 317-23.

4 “Speech of Isaac Barré, February 3, 1766,” Proceedings and Debates of the British Parliament Respecting North America, 1754-1783, R. C. Simmons and P. D. G. Thomas, ed. (New York: Kraus International Publications, 1983), 2:144; 27.

5 “Speech of Isaac Barré, January 26, 1769,” Proceedings and Debates of the British Parliament, 78; J. Wright, ed., Sir Henry Cavendish’s Debate of the House of Commons, May 10, 1768 – May 3, 1770 (London: Longman, Orme, Brown, Green, & Longmans; Hatchard & Son; Ridgway; Calkin & Budd; J. Rodwell; L. Booth; W. H. Allen & Co.; and J. Bigg & Son, 1846), 1:205-7.

6 Peter Force, ed., American Archives, 4th series, 1:166.

7 Ibid., 1:36.

8 Ibid., 1:40.

9 Parliament of Great Britain, The Parliamentary History of England (London: T. C. Hansard, 1813), 17:1178. Peter Force, ed., American Archives, 4th series, 1:46.

10 Peter Force, ed., American Archives, 4th series, 1:113-15.

11 Ibid., 1:125.

12 Ibid., 1:85.

13 Ibid., 1:184.

14 Ibid., 1:180.

15 Ibid., 1:187.

16 Ibid., 1:205.

17 Ibid., 6:270, 284-88.

18 Parliament of Great Britain, The Parliamentary History of England, 18:1426-27.

One thought on “Isaac Barré: Advocate for Americans in the House of Commons”

Very informative. Thank you for the history lesson we never heard in school. I’m hoping by your passing of this information, the children of Wilkes-Barre, Luzerne County and Pennsylvania in general will have this added to their history lesson as part of the curriculum. Along with the information regarding the Wyoming Monument and the First Nations or The Five Nations.