One of the things that make human intelligence operations so interesting is that you never know how, and for that matter whether, an operation will work out as planned.

Lt. Lewis J. Costigin’s mission as a spy for George Washington did eventually work out. But, not the first time he tried in early 1777. In his second attempt in late 1778, he was able to report intelligence of value.[1] However, the circumstances under which he accomplished this were highly unusual, to say the least. The most surprising aspect of his successful mission was that he did it in British occupied New York City, dressed in his Continental army officer’s uniform, openly walking around the city observing British activities and forces.

Costigin was a merchant in New Brunswick, New Jersey prior to the war. In November 1776 he was a first lieutenant in the New Jersey Line of the Continental army. According to his pension statement:

… after the Battle of Trenton Col. Lourey the Company general informed him that information was received that Lord Cornwallis was approaching with his army from Brunswick to attack the army at Trenton and informed him that he was directed by Gen. Washington to select a suitable person to proceed to Brunswick to ascertain the strength of the British forces that guarded Gen. Lee and their baggage. And as he was a native of that place and had been in the Mercantile business there and his family remaining in Brunswick that he was thought qualified for this undertaking upon which he volunteered his service and by the direction of Col. Lourey waited on Gen. Washington for his instructions after reviewing his orders he proceeded to Brunswick and procured all the information in his power…he was taken by a party of light horse … and was sent to New York a Prisoner of War where he remained as such for three years … and after such period of three years exchanged for a Captain of the British Army.[2]

That Costigin was captured in January 1777 is supported in his expense report for costs related to his intelligence activities in New York City which was forwarded to General Washington by Costigin’s superior.[3] Apparently when captured he was in enough of a uniform of an American officer to be treated as a prisoner of war and not a spy. In any event, once a prisoner in New York City, he was placed on parole, which allowed him freedom of movement but involved three specific pledges he had to make against his honor as an officer:

He could not involve himself in any military activities.

He could not communicate with his military colleagues, nor publically criticize any British activities.

When summoned, he must present himself to British prisoner authorities.[4]

Costigin appeared to be forgotten, or ignored by the Continental army until August 21, 1778, when Washington sent a letter to Col. John Beatty, the Commissary General for Prisoners:

Lewis Johnson Costagan a Lieut. In the 1st Jersey Regt. Was taken prisoner early in 1777. I would wish that the speediest means may be used for the obtaining his Exchange, at the same time you will observe such caution in conducting the affair as not to alarm the enemy or induce them to detain him. You will not seem over anxious, and yet take such measures as cannot fail to procure his liberty.

As soon as he comes out you will be pleased to direct him to repair immediately to the Head Quarters of the army.[5]

No official explanation has been found to explain this sudden interest in Costigin. However, in this same month Washington began planning the development of the Culper spy ring in New York City.[6] He was well aware that creation and operational development of that collection network would take time. However, he also needed current intelligence on enemy plans and activities in the city now that the British command had returned there. Perhaps Washington had in mind the use of Costigin, who had previously been selected as a spy and was known to Washington, as one measure to fill the intelligence gap until the Culper Ring could become operational.

In September, Costigin traveled from New York City to New Brunswick to await his formal exchange. Washington was informed of this in a letter from William Livingston, the governor of New Jersey, who wrote on September 21, 1778 that, “About a week ago arrived in Brunswick from New York one Crowel formerly a New Jersey man with a flag for his Boat from Admiral Gambier, for the sole purpose of his carrying to Brunswick Lewis Costigen & his family…”[7]

In his expense report to Washington relating costs of his intelligence collection activities in New York City, Costigin explained that at that time he was “… prevailed upon by the Solicitations of Major General Lord Sterling & Colonel Ogden To Stay in the City of New York after his Exchange for the space of Four Months, in order to procure & send out information respecting the movements of the Enemy.”[8]

Interestingly, Costigin makes no reference to his involvement in intelligence activities in New York City in his pension application, even some forty years after the events. Also, he gives his time as a prisoner of war to be three years, when in actuality it was about two years. This may be due to his understanding that secrets are to remain so. It might also be that since the pension was based upon his military service, his intelligence role was not a factor to consider. A third possibility is that since pension applications required witnesses or written documentation, he may not have had such supporting evidence for his intelligence activities.

It seems that after so many months wandering about New York City in his Continental army uniform Costigin had become an accepted part of the landscape. Upon his return from New Brunswick he apparently simply continued to walk about observing and talking with various people as before. While this may seem highly improbable in a logical sense, bureaucratic procedures in any large organization often create such errors. This would not be the last time it happened to the British Army.[9]

However, having been legally exchanged Costigin was removed from the pledges that accompanied his parole. Thus, he could assist Washington by reporting on events in the city. Still, to protect his identity and his current non-parole status, Costigin needed to find a covert manner to get his reports to American lines, and he used the mark Z as his signature on these reports to hide his true identity. The only clue as to how he managed to smuggle his reports out of the city is in his expense report, wherein he notes a total expenditure of sixty-five pounds which included “… sending the intelligence procured to the American lines.”[10]

Costigin’s first, of a total of three, reports is dated December 7, 1778. It includes information on a variety of subjects, and refers to three other letters of which no record seems to exist. The report states:

After Observing the Troops in Motion on the ev’ning of the second I immediately dispatched a person with what I could gather – since which I forwarded three letters carrying ev’ry matter I could Possibly learn, which were near the Facts.

Last ev’ning Genl Clinton return’d to town, and the Troops disembarking, passing to Long Island and their different Cantonments thro’ the Night.

Every Species of Provissions Especially Fresh are in great plenty, except Bread, and from the best authority I can assure you none have been issued for several days past. They are hourly expecting a fleet with flour from Home which is said to have sail’d some time ago.

The Bedford of Seventy-four Gun is Order’d home, she having lost all her Masts cannot get them here, and goes under Juries, she belongd to Byron’s fleet.

For fear of fire, Orders are Issued that all ships and Vessels remaining here to lay in New Town Creek, this winter where arm’d Vessels are to protect them.

In One of my last I Mention’d things coming [from] Shrewbury. Since I find that Most amazing Quantities come from that Quarter, within this Year not less than One Thousand Sheep, five Hundred Hogs, and Eight Hundred Quartr or up-wards’s of good beef, a large Parcel of Cheese – besides Poultry – which give [good] support to the City.

Yesterday Arriv’d seven Prizes, Two [French] Vessels bound to America: Two with Tobaco from Virginia, the Others small West Indiamen.

It is reported that Genl Vaughen is shortly to go home.[11]

This report, while general in nature, does appear to be accurate in its details, and indicates that Costigin did enjoy freedom to walk about the city and collect local gossip. There are no documents suggesting that he received any response to this report, nor that he was given any specific reporting requirements for this or his future reporting.

His second report, sent some days later, does contain more useful intelligence, and would seem to indicate that he had developed some access to individuals with knowledge of British troop movements. It is dated December 13, 1778 and states:

Since my last, nothing having turn’d up untill this day. A fleet of Jamacia Men about thirty sail are geting into the North river and are to sail in a few days under convoy of a frigate – the Emerald Tomorrow the Amazon of 32 Guns sails for England, a number of Passenge among whom, Colo. Wm Bayard, Colo. Campbell of the 22nd Regt the Major of 16th Dragoon’s name unknown, and a Parson stringer from Phila.

As yet no Acct of the three fleets sail’d under Command of Major Genl Grant. Genl Cambell and Lieut. Colo. Campbell of the 71st now appointed a Brigr by the Commander in Chief: it is believ’d by all that Grant is gone to the West India: Genl Campbell being appoint’d Governor of Pensacola it cannot be a secret his destination: Colo. Campbell seem’d of more importance; I have paid ev’ry Attention to his line, and find he has from 3000 to 3500 Men, call’d here a pretty Command, and from the best Judges and men entituled to know ev’ry thing transacted. I am of Opinion they are intended for Georgia: from which they have high expectations not only from the weakness of the place, but likewise friendship of the Citizens of that Province – I this day saw Go’vernor Tryon in the City [he] having been very ill with the Gout is retu [returned] but cannot learn who is left in Command [of] the bridge. I this day also learned that the Light Infantry from Jamacia, with the 17th Dragoon’s, and Cathcarts Legion, from Jerico, are Order’d to South and East Hampton’s and as they [take] no Provisions with them, it is believ’d they will sweep all that Country.

Bread with the Army is exceedingly [short] but Large Quantities of Rice have been taken which serve as a Substitue – the Opinion of an evacuation still prevails among numbers of the inhabitants – but I must say I cannot as yet see any Probability of it.[12]

Costigin’s final intelligence report is brief, and dated December 19, 1778:

Mr. James Willing, with Two Officers said to be deserters from the British service, at Pensacola have been lately taken in a small sloop from that Quartr bound as suppos’d to Philadelphia. The three on being brought to this place found means to make their escape from the prize, and got into the City.

Mr. Willing who is some way connected with Lawr. Kirtwright immediately repair’d to his house, but unhappily found no shelter there, he being a person of Consequence was given up and is now in confinement he being no Seaman, and taken unarm’d it is generally said he will be held up for Connelly – the other Gentlemen are not yet discover’d.

The Jamacia fleet have not yet sail’d and I find there will be in the whole 40 or 50 sail – a number of them Arm’d.[13]

From other correspondence, and Colonel Ogden’s role as indicated in Costigin’s pension paper and his operational expense report, it can be surmised that his reporting channel went directly to Ogden, and then to Ogden’s Commanding Officer Lord Stirling (William Alexander), and from Stirling to Washington. It appears Stirling may have provided Washington with a consolidated intelligence report on New York City activities, but accompanied by the reports from each source.

Washington’s only recorded reaction to Costigin’s reporting was almost lost to history. On December 30, 1778, Stirling sent Washington a communication which included information from Costigin, but it is not clear which December report it was from.[14] On January 2, 1779, Washington responded to Stirling, “I am favd with yours of the 30th Ulto. I thank you for the intelligence it contains.”[15]

However, also preserved is the draft of the correspondence, which reads: “I am favd with yours of the 30th Ulto with the information from Z inclosed. I thank you for that and what you have collected from other quarters.”[16]

Another indicator that Washington appreciated Costigin’s reporting comes from the fact that he was aware when Costigin’s reports ceased to appear. In a March 15, 1779 letter from his Headquarters at Middle Brook, Washington wrote to Brigadier General William Maxwell, “We have heard nothing of a long time from Z. Has he dropped the correspondence? Or what is become of him. If we are to depend no further upon him, you should endeavor to open some other channel for intelligence – The Season advances when the enemy will begin to stir, and we should if possible be acquainted with their motions.”[17]

Maxwell responded, on March 17, identifying who Z was and noting that he was no longer active as a reporting source: “We have several people in New York that would give us intelligence but we have none that will attempt to go for it; those that have gone formerly have been presented at the last Court, and Bills found against them; they denyed the charges but are bound to the next Court so that we cannot get them to move The person, under the Carracter of Z is out some time ago. I think he lives at Brunswick Viz. Costican.”[18]

With this correspondence, Costigin’s role in American intelligence ends with the exception of his subsequent request for reimbursement submitted through Colonel Ogden on April 4, 1782 and the brief description of his intelligence role in his pension statement of August 25, 1820.

[1]In Colonial times the word “intelligence” had a broader meaning than is currently in use. It was used to refer to any information of interest or value, and in various documents the words information and intelligence were both used to refer to details on the enemy obtained by both public and nonpublic means.

[2] Pension Statement of August 25, 1820, at www.fold3.com/image/#12766045. Pension: S. 43,337.

[3] Letter from Matthias Ogden to George Washington, April 4,1782, at http://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/99-01-02-08080.

[4]Charles Henry Metzger, The Prisoners in the American Revolution (Chicago: Loyola University Press, 1971), 193.

[5]David R. Hoth, ed, The Papers of George Washington, Revolutionary War Series, vol. 16, 1 July -14 September 1778, (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2006), 343.

[6] For information on the Culper Ring, see Journal of the American Revolution, “Abraham Woodhull: The Spy Named Samuel Culper”, May 19, 2014, by Michael Schellhammer. https://allthingsliberty.com/2014/05/abraham-woodhull-the-spy-named-samuel-culper/

[7] http://rotunda.upress.virginia.edu/founders/GEWN-03-17-02-0069 (accessed May 26, 2015).

[8] Ogden to Washington, April 4, 1782.

[9] The disinformation operation by Private Charles Morgan, of the New Jersey Light Battalion, prior to the Battle of Yorktown was also apparently assisted by British Army bureaucratic structure. Posing as a deserter, he convinced Cornwallis of false information regarding American capabilities. However, when he returned to American lines a few days later, it appears Cornwallis was not informed and continued to believe Morgan’s information. See Kenneth A. Daigler, Spies, Patriots, and Traitors: American Intelligence in the Revolutionary War (Washington: Georgetown University Press, 2014), 225-27.

[10] Ogden to Washington, April 4, 1782.

[11] Edward G. Lengel, ed., The Papers of George Washington, Revolutionary War Series, vol.18, 1 November 1778 – 14 January 1779 (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2008), 376-77. Note: No previous reports from Costigin regarding supplies from Shrewsbury have been found.

[12] Lengel, The Papers of George Washington, 399-400.

[13] Lengel, The papers of George Washington, 465.

[14] http://rotunda.upress.virginia.edu/founders/GEWN-03-18-02-0600 (accessed May 26, 2015).

[15] http://rotunda.upress.virginia.edu/founders/GEWN-03-18-02-0625 (accessed May 26, 2015).

[16] http://rotunda.upress.virginia.edu/founders/GEWN-03-18-02-0625 (accessed May 26, 2015).

[17] http://rotunda.upress.virginia.edu/founders/GEWN-03-19-02-0483 (accessed May 26, 2015).

[18] http://rotunda.upress.virginia.edu/founders/GEWN-03-19-02-0510 (accessed May 26, 2015).

7 Comments

Terrific piece Ken! Great work putting together this story together. I think this helps point out that although the Culper Ring gets a lot of press, it was one of the many successful intelligence operations that Washington, and his subordinates, ran at varying levels throughout the war. Thanks for highlighting this in a lively style.

Thanks Mike. JAR is one of the few vehicles where researchers can write short pieces in detail on such specific subjects. And, its knowledgeable audience makes the work meaningful.

Thanks! Great article couldn’t find much else about this person.

Hello Mr. Daigler,

This is a great article. I was wondering if you would know we’re he might be buried. I would like to visit and honor and pay my respects.

Thank you,

John Resto

John, my focus tends to be on the intelligence side of the war rather than a broader approach on the individual. My research indicates that after his time in New York his intelligence reporting ended and, like all really good spies, he promptly blended into the background. I do not know where he is buried, but would not be surprised if some other JAR reader could provide that information.

I am glad you enjoyed the article – Lt. Costigin is, indeed, one of the unsung hero’s of the Revolution, acting bravely in a dangerous situation.

Mssrs. Daimler and Resto,

I was so pleased to locate the JAR article when I was researching information on Lewis Johnston Costigan in order to prove him as an ancestor and a Patriot for a supplemental application with the National Society Daughters of the American Revolution. He is not in its Patriot listing. My Dusenbury line crosses with his through his daughter, Harriet Costigan, who married Thomas Dusenbury. Each one is buried in Green-Wood Cemetery in Brooklyn. Her death certificate does not name her parents. I need to document her parentage and marriage.

My research led me to the NYC Archives to find a death certificate for Lewis Johnston Costigan. No death certificates then, but I received a certified copy of “Deceased” ledger pages documenting his death on November 10, 1822, showing he died of Old Age at 80, with interment at St. John’s. Subsequently I discovered that St. John’s was the St. John’s Chapel of Trinity Church, Manhattan, with the churchyard, St. John’s Cemetery, used for burials from 1806 to 1852. The congregation moved northward in Manhattan and St. John’s was torn down, the graveyard fell into ill use and disrepair and, after a long legal battle, was purchased from Trinity for use as a NYC park. In 1896, notice was given for families to retrieve the remains of some 10,000 for reinterment elsewhere by the end of that year. Only some 250 were removed. Park construction started in 1897, opened in 1898 and was named Hudson Park, renamed James J. Walker Park in 1947. See New York Cemetery Project, Mary French.

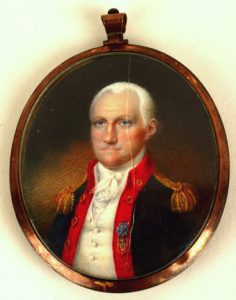

My research will continue from this point. The LJC Cameo pictured was donated to the NY Historical Society by Harry H. Lloyd in memory of his widow Adele T. Dusenbury Lloyd, dated February 1, 1945. If possible, I will pursue locating where they are buried on the chance they may have been family to retrieve LJC’s remains, one of the 250 reinterred.

Variously I have seen references to LJC’s military rank as Lieutenant, Captain and even General. I wish to identify with certainty that it is Lieutenant.

Other nuggets of information discovered have been remarkable. Will see where they lead. I had to share the above for anyone interested in Lewis Johnston Costigan’s service to this great nation of ours.

Hello Judith,

I just noticed that you responded. Thank you for the great information. If you find anything, please keep me posted. Appreciate all of the information you had researched.

John