The next time you’re in a trivia contest and the question comes up, “What was the last battle of the American Revolutionary War?” the judges will probably be looking for the predictable answer of “Yorktown.”[1]

That’s the neat and tidy answer, but it’s not true. After the defeat at Yorktown, King George III brushed it off as a minor stumbling block and decreed that the war in America should continue. He wrote to the prime minister avowing that he would “do what I can to save the Empire.”[2] Gen. George Washington, not having read twenty-first century schoolbooks, never knew Yorktown would be considered the end of the war, or famously as the “last battle of the American Revolutionary War.” He smartly assumed the British were certainly wounded with Lord Cornwallis’ surrender, but that they wouldn’t quit. The war would continue. Washington felt it was his absolute duty to keep the Continental Army together until there was a final peace treaty signed and approved.

A preliminary treaty finally came on November 30, 1782, a year after Yorktown… but there was still no formal treaty. Washington remembered what Ben Franklin had said, “The British Nation seems… unable to carry on the War and too proud to make peace.”[3] The politicians were all still talking in Paris. Washington instinctively didn’t trust the British and knew it could be a mistake to lower his guard of them, even while talks were going on. As late as January 1783, from Newburgh, New York, he wrote to Maj. John Armstrong that he suspected Parliament would still “provide vigorously for the prosecution of the war.”[4]

But in the meantime, between Yorktown and the preliminary peace treaty, there were at least forty-four more documented world-wide battles, sieges, actions, incidents, and skirmishes of the American Revolutionary War[5].

France officially entered the war in 1778, followed eventually by Spain and the Netherlands. What was once a provincial police action by the British in their American colonies soon became a world war. Britain essentially abandoned fighting the Continental Army in the stalemated northern states and switched to a southern strategy. Thinking that the population in the southernmost states was more Loyalist friendly, the strategy also allowed Britain to keep its fleet and armies closer to their real economic strong box of the Caribbean (and Jamaica, in particular). Great Britain began to focus on protecting its world-wide economic interests from French and Spanish plunder.[6] Some of these global hotspots included the West Indies, Gibraltar and the Mediterranean, Africa and India.

India, long the profitable domain of the British East India Company, was literally a world away from Great Britain and from any means of speedy communication in the late eighteenth century. Word of the signing of the Revolutionary War preliminary peace treaty in Paris didn’t arrive in India for quite a while after the ink was dry.

Thus, your correct answer to the trivia question should be, “the last battle of the American Revolutionary war was fought in India.”[7]

The Back Story

Since the 1600s, both Great Britain and France had colonies in India. But when France declared war against Britain in 1778 and entered into the American Revolutionary War, the British East India Company (who actually had its own soldiers!) decided to attack the other French colonies in India. To help out, the British government told the company that they would also send some British army regulars to India, along with some hired Hanoverians.

For history book labeling, this started the Second Anglo-Mysore War lasting from 1780 to 1784 (you can think of it as a war within a war). It was also the second of four Anglo-Mysorean wars, but there’s no need to get hung up on the numbers. The only thing you have to remember is that our indirect ally in this off-shoot war was a guy named Hyder Ali, the Sultan of Mysore. Ali had allied himself with our friends, the French, early on and because of his ferocity and military expertise, he became a real pain for Great Britain until his death[8] in December 1782. From 1780 to 1783, the Franco-Mysorean forces fought the British all over western and eastern India in far-off-sounding places like Mahé and Mangalore.

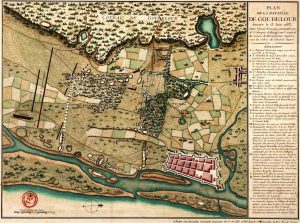

By early 1783 and now that Hyder Ali was dead, the British decided to retake the important and ancient seaport city of Cuddalore, on India’s eastern shore of the Bay of Bengal. British Gen. James Stuart left Madras with his army bound for the French-Mysorean garrison quartered in the fortress of Cuddalore. It’s not like they were all strangers there – the British and French had already battled in Cuddalore during the earlier Seven Years’ War. But this time, General Stuart came equipped to besiege Cuddalore into surrender. British command was also sending a warship fleet to reinforce Stuart’s siege through a naval blockade of Cuddalore. The French heard about it and readied their own fleet of battleships to reinforce their loyal soldiers and to battle the slightly-superior British fleet.

The last battle of the American Revolutionary War in the summer of 1783 was shaping up to be a major engagement – halfway around the world from America.

The Siege of Cuddalore (June 7 – June 25, 1783)

Under the steamy summer sun of east India, the British forces arrived outside the fortress of Cuddalore on June 7. The British army had bolstered the troops owned by the British East India Company, and had added assistance with Bengal sepoys and Carnatic battalions of the Bengal army. “The next five days were spent in landing guns, tools, ammunition, and a detachment of the 16th Hanoverians.”[9] The British formed initial siege lines facing the Cuddalore fort, stretching from the seashore to the hills. The French-Mysoreans themselves, under Marquis de Bussy-Castelnau and Sayed Sahib, formed up facing the British lines and began the construction of trenches and redoubts as protection against the expected siege and assault. To support the siege, eighteen British ships of the line (the battleships of the time) under Sir Edward Hughes, had arrived and anchored off of Cuddalore creating a naval blockade.

Just one week later, on June 13, the British decided to attack a Franco-Mysorean redoubt to put them into a better position for the coming siege. But an unplanned, all-out skirmish began with attacks and counterattacks by both sides. The ferocious fighting (each side said to have committed about 11,000 soldiers) lasted until the two warring factions counted about a thousand casualties each. Both sides retired to lick their wounds, and the French-Mysoreans fled back behind the fortress walls. General Stuart then began the siege bombardment of Cuddalore.

The (Naval) Battle of Cuddalore (June 20, 1783)

But, surprise, the French fleet under Adm. Pierre Andre de Suffren sailed up on the evening of June 16. The fifteen French ships of the line also carried 1,200 reinforcements.

“Suffren sailed to contest the blockade, though his ships were in poor shape, undermanned, and outnumbered. He cleverly maneuvered to draw the British out of the Cuddalore roadstead and occupied it himself.”[10]

Admiral Suffren asked the Cuddalore commanders if he could keep the 1,200 reinforcement troops he had transported onboard ship, so that the ship gunnery crews would be well manned. With those extra personnel aboard, “… he boldly went out to attack the superior British force.”[11]

The two fleets aligned themselves in the wind on June 20 and began cannonading each other. The three-hour long naval battle unfolded in the late afternoon, amazingly with light casualties on both sides and without a lot of damage to either fleet. Although basically a draw, the Battle of Cuddalore goes down in history books as a French victory because the British disengaged and then both fleets sailed away from each other. Soon after though, Sir Hughes and his ships set sail back to Madras since they were very short of drinking water and were experiencing a “severe outbreak of scurvy, from which nearly 2,000 men were in hospital.”[12]

That left the French fleet to be able to sail up to Cuddalore again, and Admiral Suffren was able to disembark his promised 1,200 soldiers that he had borrowed earlier from the fortress defenders, along with an additional 2,400 reinforcement troops. “Upon the departure of the British squadron to Madras, M. de Suffrein immediately proceeded to Cuddalore, where he not only returned the 1,200 land forces which had been lent by the Marquis de Bussy, but he landed 2,400 of his own men from the fleet, as a most powerful aid to the defence.”[13]

The French Counter-Siege Attack (June 25, 1783)

With the additional soldiers and replenished supplies, the French-Mysoreans inside Cuddalore decided to strike out again against the besieging British. On June 25, they repeatedly made attacks against the British lines and repeatedly were driven back, sustaining heavy losses each time. The French attacks were a disaster. Many French officers were taken prisoner, including the assault commander Chevalier de Dumas, a very high-ranking officer. Also taken prisoner was a sergeant in the Régiment de Royal-Marine, Jean Bernadotte, who survived his capture and lived through the Cuddalore expedition. In an example of a great career path, he eventually was named Marshal of the Empire by Napoléon, which led him to becoming the King of Sweden.

The Disintegration of the Siege and Word of the Treaty (June 29, 1783)

After nearly a month of fighting, both on land and in the Bay of Bengal, the British along with the French-Mysoreans were becoming weary and disillusioned. Both sides were racked with disease and thirst. The sick and wounded on both sides were dying at an alarming rate.

General Stuart felt like he’d been abandoned by British command and fired off angry letters from Cuddalore to the Madras government. He was soon fired and sent back to England in disgrace where he had to fight a duel to defend his honor; he was severely wounded.

Marquis de Bussy was also dealing with disheartened defenders because of the many failed attempts to break out of the siege. But unlike the treatment of Stuart, de Bussy was soon honored for holding out during the British siege. He was made the governor general of Pondicherry, another important port city in India, but died in 1785, just two years after the siege.

On June 29, with both sides of the Cuddalore siege disintegrating in the oppressive heat of late June, a British vessel flying a white truce flag sailed up to Cuddalore. Sir Hughes wrote, “… on June 27, I dispatched his Majesty’s ship Medea, as a flag of truce, with letters to M. Suffrein and the Marquis de Bussy.”[14] The letters carried news that the American Revolutionary War was over. An initial peace treaty had been signed on November 30, 1782, seven months before the siege and the battle of Cuddalore. But there was no way to get the news to eastern India any faster. The final Treaty of Paris was signed on September 3, 1783 and ratified by Congress a few months later. Under the terms of the treaty with the French, ironically, a curious game of India musical chairs happened. Britain gave Pondicherry back to the French, and (after all that) Cuddalore was awarded back to the British.

The final battle of the American Revolutionary War had happened. It hadn’t been fought in a New England meadow, in a forested wilderness, or in a southern swamp. It had been fought in the Bay of Bengal and outside the fortress of Cuddalore, India.

You’ll really win the trivia contest with that one!

[1] Actually Yorktown wasn’t even a battle. It was a siege. Two different things. You can correct the judges on that also, aside from what you learn in this article.

[2] George III to Lord North, February 26, 1782, in Sir John Fortescue, ed., The Correspondence of King George the Third from 1760 to December 1783 (London: Macmillan, 1927-1928), 5:326.

[3] George Washington to Nathanael Greene, September 23, 1782, in John C. Fitzpatrick, ed, The Writings of George Washington from the Original Manuscript Sources Vol. 25 (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1939), 195.

[4] George Washington to Major Armstrong, January 10, 1783 at http://memory.loc.gov/cgi-bin/query/r?ammem/mgw:@field(DOCID+@lit(gw260041)), accessed May 13, 2015; The Writings of George Washington from the Original Manuscript Sources, 1745-1799. John C. Fitzpatrick, Editor.

[5] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_American_Revolutionary_War_battles. The exact number is unknown. The brutal partisan fighting in the southern states continued and is not counted in this cited listing. One particular battle in April 1783 may have been the last battle fought on American shores. It was between British and Spanish forces and fought in Louisiana, although the location would now be considered Arkansas. It was called The Battle of Arkansas Post. A Smithsonian publication lists the final battle of the American Revolutionary War on American soil as happening in November 1782 “between American, Loyalist, and Shawnee forces in the Ohio territory.” Stuart A. P. Murray, Smithsonian Q&A: The American Revolution (Irvington, NY: HarperCollins Publishers, 2006), 103.

[6] This is in addition to the fact that Britain had to keep some of its naval fleet near its own shores to protect itself from a perceived Franco-Spanish invasion. The threat of a copy-cat revolution in Ireland was also a concern in Parliament.

[7] Andrew Jackson O’Shaughnessy, The Men Who Lost America: British Leadership, the American Revolution, and the Fate of the Empire (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2013), 14.

[8] Hyder Ali (Khan) did not die in battle, but rather from a cancerous growth on his back in December 1782. His son, Tipu Sultan, took over his father’s command of Mysorean forces in 1783. The Third and Fourth Anglo-Mysorean Wars were then fought. With the death of Tipu Sultan, Mysore finally fell in 1799 to the British East India Company forces. Incidentally, Hyder Ali was illiterate, but spoke six languages. He also invented Mysorean rockets which he used against British East India Company soldiers. These were the first rockets to be enclosed in iron casings. After the wars, the British did technical innovations to Ali’s rockets and developed the Congreve rockets… which they used against Americans in the War of 1812.

[9] Lieutenant-Colonel W. J. Wilson, History of the Madras Army (Madras: E. Keys, Government Press, 1882), 2:76.

[10] R.G. Grant, Battle at Sea: 3,000 Years of Naval Warfare (New York: DK Publishing, 2011), 169.

[11] Ibid., 169.

[12] Wilson, History of the Madras Army, 80.

[13] Edmund Burke, The Annual Register, or a View of the History, Politics, and Literature for the Year 1783 (London, J. Dodsley, Pall-Mall, 1785), 112; https://books.google.com/books?id=Mr0vAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA112&dq=Cuddalore+1,200+reinforcements&hl=en&sa=X&ei=CghZVd37KILdsAWVy4GgBg&ved=0CCMQ6AEwAQ#v=onepage&q=Cuddalore%201%2C200%20reinforcements&f=false, accessed May 17, 2015.

[14] James Boswell, “Affairs in the East Indies – App 1783; Extract of a Letter from Vice-Adm. Sir Edward Hughes to Mr. Stephens,” The Scots Magazine, Vol. 45 (1783), 685, 688; https://books.google.com/books?id=Tt8RAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA682&hl=en#v=onepage&q=Cuddalore&f=false accessed May 13, 2015.

12 Comments

A couple of corrections, some of which come from my own upcoming JAR article that looks at the last battles in all the major theaters of war, as well as from my book, “After Yorktown,” that comes out this fall from Westholme Publishing.

• Wikipedia, this article’s source of the 44 post-Yorktown actions, grossly underestimates their number. Scholars including John Robertson, Patrick O’Kelley, Mark Boatner, Todd Braisted, and Howard Peckham have identified more than 300 actions around the world.

• Contrary to footnote 5, the last battle in North America was not at Arkansas Post in April 1783, but a month later and 90 miles away when the Spanish caught up with some of the Loyalist–Chickasaw raising force.

And a comment: Hyder Ali was a brilliant innovator, as well as “ferocious” and with “military expertise.” A 19th century British commissioner to Mysore described him as “a bold, an original, and an enterprising commander, skillful in tactics and fertile in resources, full of energy and never desponding in defeat.” Even General Eyre Coote, Hyder’s British counterpart and nemesis, conceded, “Hyder had taken every measure which could occur to the most experienced general to distress us and to render himself formidable; and his conduct in his civil capacity had been supported by a degree of political address unequalled by any power that had yet appeared in Indostan.”

Hyder ran a meritocracy: Although he was Muslim, he welcomed Hindus and others to his administration based on their competency.

The illustration of him in this article is fanciful: He shaved his head and eyebrows because, he explained to an East India Company official, he didn’t want anyone in Mysore to look like him.

Finally, a caution: Gen. James Stuart is sometimes confused with Lt. Col. James Stuart (1741–1815) who was under Gen. Stuart’s command at Cuddalore. The lieutenant-colonel also became a general.

Mea culpa. It should read “Loyalist–Chickasaw RAIDING force”

Don – thank you for your insightful and well directed comments! One of the best parts of the JAR site is that good, knowledgeable discussions go on for all readers to enjoy and benefit from.

Regarding the number of post-Yorktown actions, I was sure to preface the point with “The exact number is unknown.” The “… at least forty-four” recognized actions also corresponded with the stats from the American Military History’s “Army Historical Series” publication 9105291/42040 that I use for reference. But I’m very familiar with scholars like Boatner, Peckham, and Todd Braisted and value their insights also. The feelings on the ranking of the Battle of Arkansas Post would fall into that category as well. Zeroing in on indisputable statistics to that world-wide war would be like nailing Jell-O to a tree. But your excellent points are well taken.

Your reflection on Hyder Ali is spot on. Most people would never guess that (re. endnote 8), Ali “also invented Mysorean rockets which he used against British East India Company soldiers. These were the first rockets to be enclosed in iron casings. After the wars, the British did technical innovations to Ali’s rockets and developed the Congreve rockets… which they used against Americans in the War of 1812.”

Thank you again and I greatly look forward to adding your “After Yorktown” Westholme Publishing book to my collection. Congratulations!

JL –

Great article! You’ve managed to cut through the hopeless Mysore entanglements and proxy forces to focus on the prize: the direct confrontation between England and France at Cuddalore, and retained a couple of the best tangential anecdotes. Great add to the growing JAR knowledge base – well done!

Jim – thank you, and you’re exactly right when you say “hopeless Mysore entanglements and proxy forces”. Whether the RevWar actions were in the Caribbean, the mouth of the Mississippi River, Gibraltar, in the American heartland, Canada, or off the coast of America, England, Africa, or India… the proxy forces were set loose to battle it out. Most people would never guess that the Bay of Bengal was one of the sites! Who would’a thought?

Many thanks again for your nice words.

Here’s a poser: what constitutes a “battle?” Surely there were not 44, or 300, battles after Yorktown. The naval battle of Saintes counts as a battle. The skirmishes around Charlestown SC count. But does Arkansas Post – although it’s now a National Memorial – really count? Were people on the east coast, or Europe, even aware it happened, and did it make any difference whatsoever? Your thoughts are welcome: Can we count any instance where one hillbilly fired on another as an historic event?

Agreed that not all the 300 actions were “battles.” As John said, they included “sieges, actions, incidents, and skirmishes.” In terms of battles equivalent to the Saintes, I’d say there were four campaigns after Yorktown that included at least one or more major battles that really made a difference: The Saintes, as you mentioned; the India campaign with multiple army and navy battles including Cuddalore; Blue Licks, which was part of the frontier campaign and raised rebel white settlers’ outcries to the point where the government was forced to address them; and, of course, Gibraltar.

I’d argue that the “hillbilly” actions taken in their totality did make a difference, and that London, Paris, Philadelphia, and Amsterdam were very much aware of them, even if the news came late. (The rebels even named one of their ships after Hyder Ali.)

For example, Bernardo Gálvez in Havana was kept well-informed of what his subordinates were doing in Arkansas; his British counterparts, who already had lost West Florida, cared deeply about Spanish threats; and every Indian nation closely monitored and often participated in European, loyalist, and whig actions along the Mississippi. All these minor battles and skirmishes in the Mississippi Valley helped shape the conditions that led to Andrew Jackson’s invasions of Indian and Spanish territory less than a generation later.

The Big Data of history, after all, includes the little data of “hillbillies” shooting at each other.

Will, your theoretical question of what is a “battle” (and then its obviously-connected next question: “If a battle happens in the Ohio territory and if no one hears about it, is it still a battle?”) is an underlying point. What Don replies back is valid. Like my old boss used to say, “That dog will chase its tail forever”. At some point, a writer has to make a determination for the story.

So, aside from the sources cited, I used the quote (endnote 7) from the popular book from my esteemed friend, Andrew Jackson O’Shaughnessy who wrote, “the last battle of the American Revolutionary war was fought in India.”

I realize that’s open to endless interpretations, but that’s partly the fun in discussing history.

Hi John,

Thanks again for another wonderful article. It got me thinking more about how the American Revolution turned into a global conflict especially once France, Spain and others got involved. This article plus works by others like Andrew Jackson O’Shaughnessy, who gave an excellent presentation about the Caribbean at the March Williamsburg conference, really brings the war to light beyond the 13 colonies. In the Mohawk Valley, the Battle of Johnstown, which occurred on October 25, 1781 about week after Yorktown, was the last “major” engagement of the Revolution in the Northern Department but raids were still occurring through 1782. Great stuff!

Brian

Thank you, Brian. You’re right about zeroing in on the October 25, 1781 Battle of Johnstown in the Mohawk Valley as another example of a post-Yorktown battle.

In Boatner’s Encyclopedia of the American Revolution (p. 564), he labels the action as “Border Warfare” and goes on to give a brief description of the event.

Interesting; and just one of many, many battles, skirmishes, actions, fights, encounters, fracas… and all the other synonyms out there for global engagements after Yorktown.

And thank you for your work at the Fort Plain Museum.

An interesting footnote, perhaps, is that William Richardson Davie, a southern militia/ partisan officer and later Greene’s commissary during the later stages of the Southenr Campaigns named one of his sons Hyder Ali. Davie later served as minister to France during the Quasi-War.

The last military action of the Revolutionary War was actually the withdrawal of British troops from Charleston, SC in 1789.