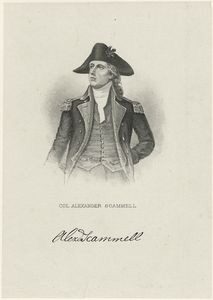

The highest ranking Continental Army officer to be killed during the Siege of Yorktown in 1781 was Col. Alexander Scammell, 34-year old commander of the New Hampshire Regiment.[1] The descriptions of his capture and wounding in the many published accounts of the siege contain inconsistencies about where he was captured and associated events. In addition, they are silent as to how he was transported from Yorktown, where he was wounded, over twelve miles to the Continental Army hospital at Williamsburg, where he died.[2] Recently-discovered evidence of the latter prompted the author to study contemporary reports of the events leading to his death with the objective of resolving those inconsistencies.

The combined Continental Army-French Army (Allied Army) under Gen. George Washington marched from Williamsburg to Yorktown on September 28, 1781 to complete the isolation of the British Army begun when the French Navy blockaded the Chesapeake Bay. During the night of September 29-30, the British commander, Lt. Gen. Charles, Lord Cornwallis, ordered the withdrawal of his forces from its outer defensive works based on his expectation that the British Fleet could break the naval blockade and bring him reinforcements. Early on September 30 American pickets, scouting in advance of the Continental Army camps near the center of the Allied Army line, determined there were no British forces in the earthworks they faced and began to probe cautiously towards Yorktown. Col. Alexander Scammell, field officer of the day that began early on September 29 and ended early on September 30, led the pickets in their probing as soon as dawn provided sufficient light, i.e. soon after 5:35 a.m.[3]

A small British cavalry patrol under Lt. Allan Cameron left cavalry headquarters at the Moore House east of Yorktown at dawn in a search for isolated Allied soldiers to capture. They probably reached the position in front of Scammell and his men, northwest of the earthwork called Poplar Tree Fort by the Americans, well before the 6:01 a.m. sunrise, i.e. during the twilight period.[4] Colonel Scammell’s account of what happened next was recorded a few days later by a visitor:

…he mistook a few of the enemy’s light horse for [Col. Stephen] Moylan’s; he thought he knew the officer in front, and was therefore not alarmed. Two of them rode up to him, one of which seized his bridle, while the other pointed a pistol at him. Being thus in their power, and enquiring who they were, a third rode up and shot him in the back, at so near a distance as to burn his coat with the powder; another soldier then made a pass at him with his sword, but being weakened with his wound, and his horse starting at the report of the pistol, he happily fell to the ground and avoided the stroke. He was then plundered, taken to York…[5]

Some of Scammell’s men were close enough to witness this episode but unable to act in time to rescue their commander. They reported what they had seen to Col. Philip Van Cortlandt who, as field officer of the day beginning September 30, had just arrived with his men to relieve Scammell.[6] Van Cortlandt described the situation thus:

I found [Scammell’s] men and relieved them; but the Colonel had, before my arrival, observed that [the British] had retired from the poplar-tree redoubt to the road in front, and mistook a British patrol of horse for our men, was under the necessity of surrendering, when one of their dragoons coming up, fired, and wounded the Colonel after his surrender, but whether the dragoon knew of the surrender, being behind him, I cannot say, but from all the information I could obtain, it was after his surrender.[7]

His report or that of Scammell’s men spread throughout the Continental camp and within a few days made its way into several journals and letters.[8]

The surviving British record of Scammell’s capture is limited to brief mention in several private journals.[9] However the substance of subsequent events in Yorktown can be surmised with a reasonable degree of confidence. During the morning British army doctors realized that the colonel was seriously wounded and concluded that they had inadequate resources to care for him, especially in the face of the coming Allied attack or siege. Scammell knew that the Continental Army had established a hospital in the empty Governor’s mansion in Williamsburg to provide care beyond that available in a field hospital, and requested parole in order to transfer to that facility. The British agreed to the parole and on the afternoon of September 30 sent under flag to the Allied lines a letter from Scammell to his next-in-command, Lt. Col. Ebenezer Huntington, asking him to send Scammell’s personal baggage and servant to Williamsburg. Huntington complied with that request and also dispatched the regimental surgeon’s mate, Dr. Eneas Munson, to Williamsburg to care for him.[10]

The British then placed Scammell in one of their boats, possibly from one of the Royal Navy vessels supporting Cornwallis, sailed it up the York River to the mouth of Queen’s Creek,[11] then sailed and rowed it up that creek to Capitol Landing, a voyage of twelve miles requiring up to six hours.[12] Virginia militiaman Pvt. Erasmus Chapman was on guard there:

[W]hile the army continued [at Williamsburg] I frequently stood sentry at a place called the stone bridge which was made over a creek that emtied into York river not far distant[.] [W]hile on duty one night a boat sailed or was rowed up the creek to the bridge, I hailed it, and deterred the boat till a file of men and an officer from our camp came; the boat proved to be a British one, and came with a flag bearing an American colonel who had been taken prisoner by them and was dangerously wounded. I may have forgotten his name but I now think the colo’s name was either Scamel or Campbell. He was immediately sent to the Doctors at Williamsburg on a litter[.] [T]he British boat was suffered to return.[13]

The wounded colonel had just over a mile to travel to the hospital in Williamsburg where he probably arrived late in the evening of September 30.[14]

The early visitor mentioned above thought Scammell would recover from the wound. Dr. Munson later reported that he remained with the colonel during the following days and initially he also thought that he would recover. Scammell told Munson and several visitors the details of his capture and wounding, confirming the account given to Van Cortlandt. On October 6 the colonel’s condition worsened and he died about 5:00 p.m.[15] He was buried with full military honors, presumably in Williamsburg though the specific location of his burial is unknown.[16] Lt. Col. David Humphreys of Washington’s staff, a friend of Scammell’s, wrote this fine epitaph:

To the Immortal Memory

of

Alexander Scammell, Esq;

Colonel of the first Regiment of New-Hampshire

(formerly Adjutant-General of the American Army)

who commanded a Regiment of Light-Infantry

at the

Siege of York in Virginia;

Where, in performing his Duty gallantly,

He was unfortunately captured,

And

Afterwards mortally wounded,

He expired 6th October 1781.

Anno Aetatis 34.[17]

[1] Henry P. Johnston, The Yorktown Campaign and the Surrender of Cornwallis 1781 (New York: Harper & Brothers, 1881), 192.

[2] “Narrative of Ada Redington,” typescript in the library of the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, 12, contains an ambiguous statement concerning Scammell’s return to the Continental Army. That statement could be interpreted to mean that the British returned Scammell to the Continental Army at Yorktown. The direct testimony by Pvt. Erasmus Chapman below proves that Redington did not know precisely how Scammell was returned to American lines, and kept his account vague on purpose. Redington’s original manuscript is owned by Stanford University whose on-line catalog states that it was written in 1838.

[3] Jerome A. Greene, The Guns of Independence: The Siege of Yorktown, 1781 (New York: Savas Beatie LLC, 2005), 114-118; John C. Fitzpatrick, ed., The Writings of George Washington 23 (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1937), 148; calculation of dawn (“Civil Twilight” or “when there is enough light for objects to be distinguishable, so that outdoor activities can commence”) based on “Spectral Calc.Com” site http://www.spectralcalc.com/solar_calculator/solar_position.php for September 30, 1781, and the latitude and longitude of Yorktown.

[4] Banastre Tarleton, A History of the Campaigns of 1780 and 1781 in the Southern Provinces of North America (Dublin: Colles, Exshaw, White, H. Whitestone, Burton, Byrne, Moore, Jones, and Dornin, 1787), 382-383, 386; A List of the Officers of the Army and Marines, with an Index (Thirty-Ninth Edition) (London, 1791), 366; calculation of sunrise based on “Spectral Calc.Com” site.

[5] Letter of October 4, 1781 published in Freeman’s Journal (Philadelphia) for 24 October 1781, Issue XXVII, 2-3, found on the website GenealogyBank.com. This letter was “written by a gentleman in Williamsburg” who also stated “I have seen his wound, and think he may recover.” Clearly he had visited Scammell in the hospital and heard from him the account of his capture. Col. Stephen Moylan commanded the 4th Regiment of Continental Light Dragoons.

[6] Philip Van Cortlandt, “Autobiography of Philip Van Cortlandt, Brigadier General in the Continental Army,” Magazine of American History 2 (May, 1978), 293; Fitzpatrick, Writings of George Washington, 152. Van Cortlandt placed the capture near the Poplar Tree Fort, which Tarleton described as a “field work…on the left [facing south] of the center, to command the Hampton road.” Washington’s October 2, 1781 letter in Fitzpatrick, Writings of George Washington, 157, says “Scammell…was wounded…as he was reconnoitering One of the Works, which had just been evacuated” which was true of the Poplar Tree Fort. Benson J. Lossing, Pictorial Field Book of the Revolution 2 (New York: Harper & Brothers, 1852), 515, places the capture near the Fusiliers’ redoubt, on the far left of the Allied line. However, that redoubt, which had not been evacuated, was in front of the French portion of the line and was not likely to have been picketed by Continentals. Tarleton, who was not present at Scammell’s capture, later wrote that the colonel was wounded while trying to escape, an account not supported by Scammell or the witnesses who described the action to Van Cortlandt.

[7] Philip Van Cortlandt, “Autobiography of Philip Van Cortlandt,” 293. Colonel Van Cortlandt clearly arrived within minutes of Scammell’s capture.

[8] “Journal of the Siege of York in Virginia by a Chaplain of the American Army,” Collections of the Massachusetts Historical Society 9 (Boston: Hall & Hiller, 1804), 105; Lloyd A. Brown and Howard H. Peckham, eds., Revolutionary War Journals of Henry Dearborn 1775-1783 (Chicago: The Caxton Club, 1939), 218 (erroneously dated October 1 instead of September 30); John Austin Stevens, “The Allies at Yorktown, 1781,” Magazine of American History 6 (New York: A.S. Barnes & Company, 1881), 20-21.

[9] Robert J. Tilden, “The Doehla Journal,” The William and Mary Quarterly, Second Series, 22 (July 1942), 247; Stephan Popp and Joseph G. Rosengarten, “Popp’s Journal, 1777-1783,” The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography 26 (1902), 40.

[10] William Feltman, The Journal of Lieut. William Feltman, of the First Pennsylvania Regiment, 1781-1782 (Philadelphia: Henry Carey Baird, 1853), 16; John Bell Tilden, “Extracts from the Journal of Lieutenant John Bell Tilden, Second Pennsylvania Line, 1781-1782,” The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography 19, No. 1( 1895), 59; Benson J. Lossing, Reflections of Rebellion: Hours with the Living Men and Women of The Revolution (London: The History Press, 2007), 118; James D. Thacher, A Military Journal during the American Revolutionary War, from 1775 to 1783 (Boston: Richardson and Lord, 1823), 319-320, 337. Feltman’s journal contains the statement that Scammell’s clothing was to be sent “to Williamsburg, where he would be sent on parole as soon as his wound was dressed” indicating that the British planned to send Scammell to Williamsburg that day rather than turn him over to the Americans to transport to Williamsburg; as will be seen, that is what occurred. Some accounts state that Scammell was paroled on September 30 and others say October 1. Since he was seriously wounded and the British agreed to parole him on the afternoon of September 30, there would have been no reason to keep him in Yorktown for another day; hence the statement in the text that he was sent to Williamsburg on September 30. Dr. Thacher seems to be the authority for the statement that Washington requested the parole of Scammell; however, no documentation of such a request, which would probably have been made on September 30, has been found.

[11] “Carte des Environs de Williamsburg en Virginie ou les Amees Francoise et Americaine ont Campe’s en Septembre 1781. Armee de Rochambeau, 1782.” Map Division, Library of Congress; National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Chart 12243, “York River-Yorktown to West Point.” The former names this stream “Queen’s Creek” while the latter calls it “Queen Creek.”

[12] Jack Coggins, Ships and Seamen of the American Revolution (Harrisburg: Promontory Press, 1969), 41-42; Andrew Norris emails to Bill Reynolds, March 29, 2015, 30 March 2015, 26 April 2015, and 27 April 2015 re: York River and Queen’s Creek; Log of HMS Fowey, September 29 – October 1,1781, ADM 52/1748, UK National Archives, Kew. The boat used could have been the launch or cutter from the frigate Chalon. Andrew Norris of the York River Yacht Club provided insight as to the range of time required to sail (supplemented by rowing) from Yorktown to Capitol Landing, based on wind direction from Fowey’s log. Assuming the journey began soon after Scammell’s letter was delivered to the American Army on the afternoon of September 30, arrival at Capitol Landing should have been during the early evening. Based on “Spectral Calc.Com” sunset was at 5:50 p.m. so arrival would have been in darkness lit by a nearly full moon, which rose about 5:30 p.m.

[13] Revolutionary War Pension Application (RWPA) R1867 for Erasmus Chapman, filed in 1832, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, DC, Record Group 15, “Records of the Veterans Administration,” microfilm publication M804. A copy of the original document was accessed via the website fold3.com. Chapman served in Capt. John Tankersley’s Company of militia from Spotsylvania County, Virginia. RWPA S30457 for Nathan Hawkins states that this company moved from Williamsburg to Yorktown around October 9. On September 30 it was acting as a rear guard for the Allied Army that had marched to Yorktown two days earlier. According to RWPA S48512 for John Tankard, the “Doctors at Williamsburg” included Tankard, Matthew Pope, and John M. Galt. The “stone bridge lately erected at the Capitol Landing” is mentioned in the Virginia Gazette, March 24, 1777. According to Cara Harbecke and John Metz, Phase I Archaeological Testing at Capitol Landing (Williamsburg: Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, 2005), 2, remains of the stone bridge could still be seen in 1977.

[14] This mode of returning Scammell to the Continental Army requires comment. While it was more comfortable for him than a wagon ride from Yorktown to Williamsburg, it required far more effort by the British. A generous view is that they realized he was badly wounded and wished to get him to a hospital which could treat him as rapidly as possible.

[15] Lossing, Reflections of Rebellion, 118; “Open letter to Earl Cornwallis from An American Soldier,” dated at Annapolis October 30, 1781 in Pennsylvania Gazette, November 14, 1781, 1; Letter of October 4, 1781 published in Freeman’s Journal (Philadelphia) for October 24, 1781, Issue XXVII, pages 2-3; Stevens, “The Allies at Yorktown, 20-21; Johnston, The Yorktown Campaign, 175; Octavius Pickering and Charles Wentworth, The Life of Timothy Pickering 1 (Boston: Little, Brown, and Company, 1867), 303. The writer of the October 30 letter stated that “the circumstances are precisely as related by the Colonel himself.” Charles Coffin, compiler, The Lives and Services of Major General John Thomas, Colonel Thomas Knowlton, Colonel Alexander Scammell, Major General Henry Dearborn (New York: Egbert, Hovey & King, 1845), 100, gives Dr. Thacher as the authority for the statement that Scammell was wounded after surrendering. Thacher, who remained at Yorktown throughout the siege, must have obtained that information from Dr. Munson when the latter returned to Yorktown after Scammell’s death.

[16] Philip Van Cortlandt, “Autobiography of Philip Van Cortlandt,” 293-294; William O. Clough, “Colonel Alexander Scammell,” The Granite Monthly: A New Hampshire Magazine, Vol. 14, No. 9 (September 1892), 273; Meredith Poole email to Bill Reynolds, April 3, 2015, re: Burials in the Garden of Governor’s Palace; Coffin, Lives and Services, 100. Find-A-Grave Memorial #51790804 says that Scammell is “reportedly buried among the Revolutionary War graves located in the garden of the Governor’s Palace” but Meredith Poole, Staff Archeologist, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, notes that there is no record of names of the 158 burials in the garden of the Governor’s Palace and that efforts to identify them have not been successful. Since records cited below indicate a marker was placed over the colonel’s grave, he may have been buried in the Bruton Parish cemetery. No marker is extant.

[17] Stevens, “The Allies at Yorktown,” 21; Boston Evening Post (Boston), November 24, 1781, Vol. I, Issue 6, 3; Frederic Kidder, History of the First New Hampshire Regiment in the War of the Revolution (Albany: Joel Munsell, 1868), 104. The full epitaph was on “ a Stone erected by the Army” (or a “monumental tablet”) and included a poem that is omitted here. Frank Landon Humphreys, Life and Times of David Humphreys 1 (New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1917), 224 contains a slightly different version of the epitaph and poem.

9 Comments

Salut –

since you quote Redington maybe you should also mention that Scammell was not popular with his men; Redington for one was glad to see him dead.

About this time our Col. Scammell was out reconnoitering the enemy’s position, accompanied by some other officers on horseback,

when a party of British Cavalry rushed upon them from a copse of

pines, fired on them and mortally wounded Scammell, and made him

prisoner. The rest escaped. He was taken into Yorktown, but they

not wishing to be troubled with him, sent him out to his friends under

the protection of a Flag of Truce. He was then sent to Williamsburg,

lying up York river, and I was requested to go and assist in taking

care of him, but not owing so muoh good will, I declined the appointment,

and my messmate, Uriah Ballard, was selected in my place, who

went and remained with him a few days, when he died. The men did not

at all regret his loss, but said it was. just punishment tor his

extreme severity in carrying into effect so rigid a discipline.”

There are a number of examples in Redington’s account of how Scammell mistreated his men.

Bob

Bob,

I was aware of Redington’s sentiment when I wrote the article. Since it reflected on the period prior to the siege, I decided to leave it out since my focus was on Scammell’s last days. Redington’s comments are certainly relevant to a more comprehensive study of Scammell’s service.

Bill

It is worth noting that Asa Redington was at the time 19 and a fairly young private who had served one year beginning in the summer of 1779 before enlisting again in February of 1781. Uriah Ballard was three years older and had been a drummer in Scammell’s 3rd New Hampshire regiment since 1777 and would have been accustomed to Scammell’s norm for a high level of discipline. Scammell would likely have known Ballard much better as well. Redington served with the 3rd NH regiment after they returned from the Iroquois Expedition and in their campaign in New Jersey in 1780, which was fraught with a comparative lack of discipline – it was not a good year for that regiment, and it was disbanded at the end of that year. That Redington was chosen to be in Scammell’s light regiment in 1781 speaks well of him. Like Redington, I was a private in the U.S. Army at age 19 and did not have high regard for a commander’s effort to instill military discipline. That Redington’s opinion did not change over the course of his life is unfortunate, not surprising. There was also a pronounced class difference between a Harvard-educated Colonel who was at home in the inner circles of the Army’s leadership and a brash young private who may have been the social glue for his mess-mates, but perhaps not so comfortable in Scammell’s company.

Bill, the fact that Col. Scammell was though to be recovering is a great example of the state of care in AmRev hospitals. Your article us also an example of the deference that both armies provided to officers. Very enjoyable and illustrative read!

The idea that Scammell was unpopular with his men is simply not true. Peleg Wadsworth, John Brooks and Henry Dearborn all named their sons after him; a well known elegy to him was published at the time; the Marquis de Lafayette offered a public toast to “Yorktown Scammell” on his tour of America in 1824-25.

Readington’s account was made 57 years after the events in question, which hardly counts as a reliable source.

For having studied Redington’s account and his pension application, I have found much of it to be very reliable and can be corroborated independently. It is a bit jumbled and rambling, but his insights into the second battle of King’s Bridge in 1781 and the involvement of Washington’s Life Guard match with Gen. Lincoln’s casualty report and other accounts. Not all 19-year old privates thrive on a diet of intense military discipline. I wouldn’t be surprised if Redington and Scammell were mutually irritating to one another and neither would have wanted the other’s company. Lafayette knew Scammell well from Valley Forge onward and I suspect they got on rather well. Note the above comment about class with respect to officers and enlisted.

Will,

You make a very good point. Scammell was certainly well-regarded by many of his contemporaries, in spite of what Redington said. Most enlisted men of the day disliked military discipline so Redington may have been venting on that subject in his comments about Scammell. I came away from my research with the feeling that Scammell had been an excellent officer.

Bill

Did the British officer that murdered Scammel ever get punished for his crime?

I am not aware that he did.