In August 1779 Continental army surgeon Jabez Campfield wrote, “How hard is the soldier’s lott who’s least danger is in the field of action? Fighting happens seldom, but fatigue, hunger, cold & heat are constantly varying his distress.” In the same vein, eighteenth century common soldiers spent much more time preparing meals, digging fortifications or latrines, chopping and hauling wood, and myriad other mundane tasks, than facing the enemy in battle. One of the lesser-known roles for a soldier was acting as servant to one or several officers.[1]

Officers of both sides during the War for American Independence were allowed one or more personal servants, also called waiters, but the practice was regulated. November 1776 Continental army orders stipulated, “No Boys (under the idea of Waiters, or otherwise) or old Men, to be inlisted …” Waiters (sometimes also called servants, batmen, or “bowman”) accompanied their masters wherever they went. Directions for making unit field returns in March 1779 mentioned this: ”Under Rank and File in the first column are to be inserted all men fit for duty, in which number are to be included all officers waiters belonging to the Army (who are ever to go on duty with their Masters, making part of the detail).” Furthermore, soldier-waiters were expected to carry arms during drill and in line of battle, though in reality this did not always occur. On May 4, 1779, Gen. George Washington directed that the army’s brigades practice Maj. Gen. Friedrich Wilhelm de Steuben’s new manual of discipline and maneuver, “and as a single man’s being ignorant of the principles will often cause disorder in a platoon and sometimes in a battalion, no waiter or other soldier is to be exempted from this exercise.” This was reiterated a week later: “The Commanding officers of regiments are to be answerable that no Waiter or other person absents himself from the Exercise on any pretence and the Generals and Inspectors of Brigades will visit the regiments and see that this order is strictly obeyed.” At month’s end, the commander-in-chief seemed to relent: “No Arms to be delivered to Waggoners, Waiters of the General Field or Staff officers but only to those men who are to appear in Action.”

No official allotment of servants to officers prior to 1782 is known. One early intimation dates from November 1778, to the commander of Sheldon’s 2nd Dragoons: “A field officer is to be allowed forage for four horses only including his servants. A captain forage for 3 horses including his servants, and a subaltern forage for two horses including his servants.”[2] This likely alludes to one servant per officer, with the additional mounts being pack horses for baggage. In early 1782, for the first time during the war, an authorized allotment of servants was announced. From Philadelphia, on January 19, General Washington directed that, “Commanding Officers of Regiments or Corps are not in future to furnish Servants or Waggoners from their Corps on any pretext whatever, without an express order from the Commander in Chief …”[3] Standards were set as follows:

Lt. Colonel Major Two each One with Arms one without Arms

Captain Subalterns Surgeon Mate each one Servant with Arms

Cavalry Colonel Lt Colonel Two without Arms

… The General and Military staff and officers not belonging to Corps are to be allowed Servants in the following proportions, and when they are not otherwise provided may take them from the Army viz.

Major General four Servants

Brigadier General four do.

Colonel Two do.

Lt.Colonel One do. without Arms.

Major One do.

Captains One do.

Aid decamp One do.

Major of Brigade one do.[4]

The British army had overall stipulations that could be altered by local commanders as needed. During his 1777 campaign into New York Lt. Gen. John Burgoyne directed “that every Regiment should be upon the same regulation … that the Servants and Batmen be allowed as follows:”

| Servants | Batmen | |

|---|---|---|

| Field Officers | 1 | 2 |

| Captains | 1 | 2 |

| Subalterns of a Company | 2 | 1 |

… The Batmen to be always armed, and to form the baggage Guard. The Servants to be considered as effective in the Ranks, and are to attend at every evening parade; the other parades and roll callings are excused, unless the Regiments are ordered under Arms.[5]

In mid-winter 1781 Lt. Gen. Charles, Earl Cornwallis’s forces advanced into North Carolina. At Ramsour’s Mill on January 24 he reiterated the “Regulations respecting Negroes & Horses”:

| Horses | Negroes[6] | |

|---|---|---|

| Field Offrs. of Infry | 3 | 2 Each |

| Captns. Subns. & Staff | 2 | 1 [ditto] |

| Serjts. Major, & Or Mr Serjts. | 1 | 1 |

| No Woman or Negroe to :possess a Horse. |

The black retainers referred to were servants likely doubling as packhorse man.

Five days after the action at Guilford Courthouse, on the road to New Garden, numbers of servants, batmen and horses were adjusted once more.

Head Qrs: Camp, Near Deep River 20th March 81[7]

… it is his Lordship’s wish that the Number of Bat Men Servants & Orderlys may be greatly decreased the Necessity of the Service requiring every means what ever may be used to Strengthen the files in each Corps, & that those Men permitted to continue in Such Imploy shall be of the worst Marchers.

Genl. O’Hara is pleased to Make the following regulations for the Brgd. of Guards …

| No. [of servants/bat men] | No. | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bd. Genls | 2 | Gl. Staff Offrs. | 1 | Surgeons | 1 |

| Commdant | 1 | Regl. Staff | 1 between two | ||

| Compy. | 1 to each | ||||

| [officers] |

While the proportion of black soldiers serving as officers’ waiters may have been higher in southern Continental regiments, throughout the army most waiters were probably white, given the relatively small numbers of blacks in Continental regiments. One hundred and five pension applications were examined in a preliminary study of African Americans in southern Continental regiments. Of those, nine of fifty-six Virginians told of serving as an officer’s waiter or batman. Three of those said they served as a “Bowman,” likely a colloquial pronunciation of batman. From the French cheval de bât (pronounced bah) for packhorse; the term could be used to denote a servant or waiter, but a batman was also responsible for pack or “bat” horses used to carry baggage. Several men recorded the officers they served, including James Harris’s time as servant to James Monroe (“then Major of horse & Aid de Camp to [Maj. Gen, William Alexander] Lord Stirling”), mulatto James Cooper’s 1780 service as waiter to Col. Abraham Buford (11th Virginia Regiment, later the 3rd Virginia Detachment of 1780), and James Wallace as cook for Lt. Col. Charles Porterfield of the Virginia State Regiment, before the colonel’s death at the Battle of Camden. The single black soldier found for Georgia was, by turns, waiter to major generals de Steuben and Arthur St. Clair. One South Carolinian was an artillery matross who occasionally did duty as servant to Col. Barnard Beekman, 4th South Carolina artillery, and a North Carolinian waited upon Brig. Gen. Jethro Sumner for thirteen months late in the war.[8]

A study of muster rolls for the New Jersey regiments from 1777 to early 1779 reveals that of ten soldiers listed as waiters from September 1778 to February 1779, all were white. These men all served with officers detached from their company, or served regimental and brigade commanders. There must have been waiters attached to the other company officers, but the men were not named as such possibly because they were not on detached duty. In January 1781 a “List of the Men of Col. Spencer’s Regiment belonging to the Jersey Line” contained seventy-two soldiers, twelve of whom were described as “Waiters, Absent.” The colonel and major of the regiment each had two waiters, while two captains, four lieutenants, the surgeon and a major of the New Jersey brigade each had one waiter apiece. James Condon, thirty-three years old at the time of his enlistment in May 1777, recalled of his service, “enlisted … for and During the war … in the Company Commanded by [Capt., later Major] John Hollinshead belonging to the second Jersey Regiment … he continued to serve … near six years and after the takeing of Cornwallis … was not in the battles … being a Waiter.” And, reiterating the use of white servants, some not soldiers, Georgian Dr. William Read, traveling north to join Washington’s army in June 1778, “made some improvements in his arms and travelling equipments, discharged a drunken servant and employed a steady, respectable Englishman,” named John Houston.[9]

Lt. John Tilden, serving with one of the Pennsylvania battalions in 1782, described some duties of servants in the field, writing from near the Edisto River in South Carolina:

January 9. – Make an addition to our hut; very bad off for want of furniture. … Dispatch two of our valets to head quarters.

January 10. – Spend the day in reading Spanish novels. Our valets arrive this afternoon-bring tents which relieve us very much.

[Then, operating against British forces occupying James Island in the Stono River.]

January 13. – Move up two miles from [Stono] river, lay in ye woods all day and eat potatoes. Our boys [waiters] not coming down with our bedclothes, we pass the night horridly …

January 14. – Our boys bring down something to eat …[10]

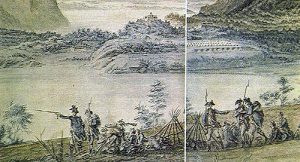

A good servant was close at hand when needed. Thomas Anburey, a volunteer serving with the 24th Regiment under General Burgoyne in northern New York, wrote that just after the battle at Freeman’s Farm, “My servant … arrived with my canteen, which was rather fortunate, as we stood in need of some refreshment after our march through the woods, and this little skirmish. I requested [Lieutenant] Dunbar [of the Royal Artillery], to partake of it … sitting down upon a tree …”[11]

At the June 23, 1780 Battle of Springfield, New Jersey, Pvt. Thomas Hobbs of the Brigade of Guards “was servant to Col. [Frederick] Thomas at the time and with the brigade.” Hobbs testified at a court martial that he, “had the care of a horse and a pair of canteens belonging to Col. [John] Howard , and of a few things belonging to Col. Thomas …” After stopping to “repair the trappings of the horse or canteens,” Hobbs followed the Brigade of Guards as it moved towards the enemy.[12]

Waiters on campaign were sometimes in or near combat. At Freeman’s “a bat-man of General Fraser’s [British Brig. Gen. Simon Fraser] rescued from the Indians an officer of the Americans …” Ensign George Inman, 17th Regiment of Foot, met a Philadelphia woman during the British occupation of that city and married her on April 23, 1778. He wrote in his memoirs that, “on the 16th June we evacuated the City, crossed (at) Cooper’s ferry, and I had a Coach for the convenience of my wife, my man servant and his wife who was also my servant, attended her … We … met with very little obstruction from the Enemy … until we came to Monmouth … we halted the 27th, the Enemy in parties making their appearance at every avenue in front of our advance posts …” After the June 28 Battle of Monmouth, “We marched on our Route towards Sandy Hook abt 12 at night without being further molested by the enemy. The next morning abt nine I got up to that part of the baggage where my wife was, she remaining in the Coach since she had left me, the Baggage had been attacked and my dear Mary very narrowly escaped being shot.” Unless they had run off, the Inman servants must have come under fire, too.[13]

On the American side of the Monmouth battle, Dr. William Read reached the field late in the day and “when he rode into the thick of the battle, his servant [Peter Houston] all the time remonstrating with him to go no further, reminding him of a promise ‘not to carry him onto battle.’”[14] Of that same action G.W. Parke Custis, General Washington’s step-grandson and adopted son, recounted a secondhand story,

A ludicrous occurrence varied the incidents of the 28th of June. The servants of the general officers were usually well armed and mounted. Will Lee or Billy, the former huntsman and favorite body-servant of the Chief, a square muscular figure, and capital horseman, paraded a corps of valets, and riding pompously at their head, proceeded to an eminence crowned by a large sycamore tree, from whence could be seen an extensive portion of the field of battle. Here Billy halted, and having unslung the large telescope he always carried in a leathern case, with a martial air applied it to his eye, and reconnoitred the enemy. Washington having observed these manoeuvres of the corps of valets, pointed them out to his officers, observing, ‘See those fellows collecting on yonder height; the enemy will fire on them to a certainty.’ Meanwhile the British were not unmindful of the assemblage on the height and perceiving a burly figure well mounted, and with telescope in hand, they determined to pay their respects to the group. A shot from a six-pounder passed through the tree, cutting away the limbs, and producing a scampering among the valets …[15]

Francis John Brooke, who served as a lieutenant in the 1st Continental Artillery Regiment, recounted after the war,

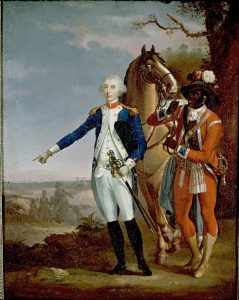

At Williamsburgh [Virginia] in 1824, on our return from York, there came an old man by the name of Powell, who had been the Marquis’ guide, after the army fell down between the two rivers James and York, and he asked Gen. LaFayette if he remembered the fine horse that was killed under him, at the battle of Green Spring, to which the General replied, the horse was a very fine one … but he was not killed under him, he had a leg broken by a six pounder, and he made his bowman cut his throat.[16]

One British officer’s servant matched his master’s martial character and idiosyncratic manner. Richard St. George Mansergh St. George was a lieutenant in the 52nd Regiment’s light infantry company; his friend Lt. Martin Hunter noted,

St. George and I were great friends. He was a fine, high-spirited, gentleman-like young man, but uncommonly passionate. He had a little Irish servant, the most extraordinary creature that ever was. He had been a servant in the family a long time, and was the ugliest little fellow I ever beheld. He was very much marked with the smallpox, had a broad white face, little blue eyes, and lank long hair. St. George always called him the Irish priest. This little man was to the full as passionate as his master, and frequently provoked him to such a degree that I often expected he would have killed him. St. George was quite military mad, and the man copied the master in everything. When the man was fully equipped for action, he was a most laughable figure as was ever seen. He wore one of his master’s old regimental jackets, a set of American accoutrements, a long rifle and sword, with a brace of horse pistols, and was attended by two runaway Negroes equipped in the same way. On a shot being fired at any of the advanced posts, master and man set off immediately – the master attended by a man of the Company named Peacock … a famous good soldier. I have often been surprised that they were not killed.[17]

Corporal George Peacock, the soldier named above, attended Lt. St. George well: when the officer was severely wounded in the head at the battle of Germantown in October 1777, “he was carried off the field by Peacock, who behaved like himself, otherwise St. George must certainly have been taken prisoner.” St. George asked Lt. Hunter “to take good care of Peacock, and gave him fifty guineas.” Peacock, a Yorkshire man who had joined the 52nd Regiment in 1763 at the age of sixteen, continued in the army until 1799 when he was discharged and received a pension.[18]

Lt. Hunter wrote that while campaigning in November 1776,

The 52nd Light Company was quartered in a house, the cellar of which was full of uncommonly fine Madeira … The next morning when we marched, Collins, the Captain’s servant, who liked a drop as well as his master, had loaded the Captain’s horses with so much, that they could scarcely move off the ground. Everything had been thrown away to make room for the Madeira, but it would not all do; three dozen must have been left behind, if St. George had not, very good-naturedly, put it on one of his horses.[19]

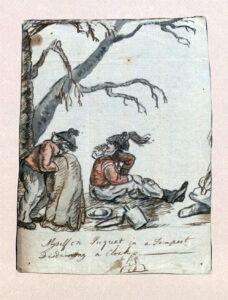

Lieutenant St. George also “drew caricatures uncommonly well, and I prevailed on him one day to draw himself and man in a violent passion, which he did so well, and so like, that everybody knew it immediately. Bernard, his servant, was lying on his back, and St. George, with one foot on his breast, flourishing a sabre over his head, telling him to say a short prayer, for that he had not more than a minute to live.” Bernard may have been Collins’ first name or one of the black retainers mentioned above by Hunter.[20]

Was taking servants from the ranks, as done by Continental army officers, detrimental to the service? The answer is, not at first, but eventually. In January 1779 General Washington told the Board of War that the practice was well in hand,

Some little time before I left Fredericksburg I had a very minute inquiry made into the number of Soldiers employed as Officers servants, and I had the satisfaction of finding … that the number was not more than common usage and the necessity of the Case required. In some particular instances where he found more soldiers returned as Waiters than was justifiable or reasonable, he mentioned the matter to the Officers employing them, and he … [had] the injury redressed … That Officers should be limited to a number of servants, in proportion to their Rank I think highly proper, and had I not found from Colo. Wards representation … that the number so employed was not more than sufficient, I should have made some regulations on that head.[21]

In March 1780 Congress passed a resolution that gave the commander-in-chief the authority “to make the most salutary regulations possible for modifying the practice of taking Men from the regiments to act as servants to Officers, which has heretofore been attended with many bad consequences.”[22] Their recommendation was that,

every Officer who by such regulations shall be intitled to a servant and who shall inlist to serve during the war a youth not under fifteen nor exceeding Eighteen years of age, and who from appearances is likely to prove an able bodied soldier, such Officer shall retain the Youth so inlisted as his servant until in the opinion of the Inspector Genl. or one of the sub-inspectors he shall be fit to bear Arms and the Youth shall receive the bounty Money, Cloathing, pay & rations of a soldier … In case of the death or resignation of such Officer, the servant to be turned over to some other Officer in the regiment intitled to a servant … any Officer intitled … to a servant who shall bring into the field with him a servant of his own, the Officer in such case not to be allowed a servant out of the Line.[23]

This same resolve, unchanged, was issued again one year later. Whether the recommendation was actually implemented is not known.

General Washington was finally compelled to act in mid-January 1782.

The Operating force of the Army having Suffered great diminution by the Number of Soldiers made use of as Servants by persons of different denominations not immediately connected with the line;

The General anxious to have the Regiments in the most collected State and as respectable as possible at the opening of the ensuing Campaigne, Orders that in future, no person belonging to the civil Staff be permitted to take a Soldier as a Servant, and that those Gentlemen in that Department who now have such, return them to their respective Regiments, or Corps, on or before the first day of April next, by which time he hopes they will be able to provide Themselves otherwise without inconvenience.

Officers Commanding Corps are desired to pay particular Attention to this order, and directed immediately to recall such of their men as are absent without proper authority: especially those with officers who have retired from the Service.

The General is astonished to find by the returns that some of the absentees are accounted for in the manner last Mentioned.[24]

The following day an order stipulating an army-wide standardized allotment of servants according to rank or function was issued, as described earlier in this article, three months after the British surrender at Yorktown. The great majority of Continental troops were sent home for good in June 1783, only a year and a half after this order.

[1] Journal of Surgeon Jabez Campfield, Spencer’s Additional Regiment, August 4, 1779, Journals of the Military Expedition of Major General John Sullivan Against the Six Nations of Indians in 1779 (Glendale, NY: Benchmark Publishing, 1970), 53.

[2] General orders, November 10, 1776, in John C. Fitzpatrick, ed., The Writings of George Washington from the Original Manuscript Sources 1745‑1799, vol. 6 (Washington, DC: GPO, 1932), 262-263. General orders, March 11 and May 4, 1779, ibid., vol. 14 (1936), 224-225, 488; General orders, August 7, 1782, ibid., vol. 24, 487-488; General orders, August 11, 1782, ibid., vol. 25 (1938), 7-8; General orders, May 12, 1780, ibid., vol. 18 (1937), 350-351, 407; Washington to the officer commanding Sheldon’s Dragoons, November 26, 1778, ibid., vol. 13 (1936), 339.

[3] General orders, January 19, 1782, ibid., vol. 23 (1937), 450-452.

[4] Ibid.

[5] E.B. O’Callaghan, ed., Orderly Book of Lieut. Gen. John Burgoyne from his entry into the State of New York until his surrender at Saratoga, 16th Oct., 1777 (Albany: J. Munsell, 1860), 87-88.

[6] A.R. Newsome, ed., “A British Orderly Book, 1780-1781,” North Carolina Historical Review, vol. IX, no. 1 (1932); IX, 2 (1932); IX, 3 (1932); IX, 4 (1932).

[7] Ibid.

[8] Material gleaned from online transcribed pension files collected at Southern Campaign Revolutionary War Pension Statements & Rosters, http://www.southerncampaign.org/pen/ (when my gleaning ended on 4/14/2011, 10,788 pension applications and 73 roster transcriptions were posted). 105 African-American veterans’ pensions found using the search terms “a free black,” “black,” “color,” “colour,” “molatto,” “mulatto,” and “Negro.” Breakdown is as follows: 1 Delaware; 10 Maryland; 56 Virginia, 32 North Carolina, 5 South Carolina; 1 Georgia.

[9] Muster rolls of the 1st, 2nd, 3rd and 4th New Jersey Regiments, Revolutionary War Rolls, 1775-1783, National Archives Microfilm Publication M246, Record Group 93, reels 55 to Reel 62. January 1781 “List of the Men of Col. Spencer’s Regiment belonging to the Jersey Line” contains seventy-two soldiers, twelve of whom are described as “Waiters, Absent,” Israel Shreve to Washington (enclosure), “A List of the Men of Col. Spencer’s Regiment …,” January 8, 1781, George Washington Papers, Presidential Papers Microfilm (Washington, DC: Library of Congress, 1961), series 4, reel 79.

James Condon (S34220), Index of Revolutionary War Pension Applications in the National Archives (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1976), and National Archives Microfilm Publication M804.

“Reminiscences of Dr. William Read, Arranged From His Notes and Papers,” R.W. Gibbes, M.D., Documentary History of the American Revolution: Consisting of Letters and Papers Relating to the Contest for Liberty, Chiefly in South Carolina, From Originals in the Possession of the Editor, and Other Sources. 1776-1782 (New York: D. Appleton & Co., 1857), 255.

[10] “Extracts From the Journal of Lieutenant John Bell Tilden, Second Pennsylvania Line, 1781-1782,” Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography, vol. 19 (1895), 218-219.

[11] Thomas Anburey, Travels Through the Interior Parts of America in a series of letters by an officer (London: Printed for William Lane, 1789), vol. I, letter XXXVIII, Camp at Freeman’s Farm, 412.

[12] The Trial of the Hon. Col. Cosmo Gordon, of the Third Regiment of Foot-Guards, for Neglect of Duty before the Enemy, on the 23d of June, 1780, near Springfield, in the Jerseys: Containing the Whole Proceedings of a General Court-Martial, Held at the City of New-York on the 22d of August, and continued … to the 4th of September, 1782 (London: Printed for Geo. Harlow, St. James’s Street, 1783). The Brigade of Guards was a composite corps formed for American service from officers and soldiers of the three British regiments of Foot Guards. Private Hobbs, Col. Thomas and Col. Howard were all from the 1st Foot Guards.

[13] Anburey, Travels Through the Interior Parts of America, vol. I, 411. George Inman, “George Inman’s Narrative of the American Revolution,” The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography, vol. VII, no. 3 (1883), 237-248.

[14] “Reminiscences of Dr. William Read,” Documentary History of the American Revolution, 255.

[15] G.W. Parke Custis, Recollections and Private Memoirs of Washington (Washington, DC: William H. Moore, 1859), 28-29.

[16] Francis J. Brooke, A Family Narrative being the Reminiscences of a Revolutionary Officer (Richmond, VA: MacFarlane and Fergusson, 1849), 18-19; see also, The Magazine of History, with Notes and Queries, extra numbers 73-76, vol. XIX (Tarrytown, NY: William Abbatt, 1922), 90-91.

[17] Martin Hunter, The Journal of Gen. Sir Martin Hunter (Edinburgh: The Edinburgh Press, 1894), 21-22.

[18] Ibid., 22. Muster rolls, 52nd Regiment of Foot, WO 12/6240, British National Archives. Discharge of George Peacock, WO 121/42/174, British National Archives.

[19] Ibid., 20-21.

[20] Ibid., 21-22.

[21] Washington to the Board of War, January 9, 1779, Fitzpatrick, The Writings of George Washington, vol. 14 (1936), 497-498.

[22] Continental Congress, Resolution on Officers’ Servants, March 11, 1780, and copy of the same Congressional resolution, March 11, 1781, George Washington Papers, Presidential Papers Microfilm (Washington: Library of Congress, 1961), series 4.

[23] Ibid.

[24] General orders, January 18, 1782, Fitzpatrick, The Writings of George Washington, vol. 23 (1937), 449.

3 Comments

Now there’s a great quote: “He was carried off the field by Peacock, who behaved like himself….”

This is a great article! It brought to mind two other Revolutionary War accounts of Officers’ servants.

The first was Major John Andre’s servant being sent across enemy lines with a clean uniform for the Major during his incarceration and later execution for his part in the attempt to turn West Point over to the British.

The second has to do with the 20th century forensic study of the skull of Dr Joseph Warren who was killed at Bunker Hill.(http://www.derekbeck.com/1775/info/stories-of-warrens-death/) The study was done using 19th century images rendered of his skull and the then subsequent studies to determine the caliber of bullet that struck him.

This study states that the shot was fired by a small caliber hand gun. The shot striking him in the right cheek, traveling through and out the back of the head. The authors then determined that the shot must have been fired by an Officer’s servant. It also proves, at least in my way of thinking, that the statement made in later years by the British Officer Small (Smallwood?) that he had spoken with Dr Warren just before he expired cannot be true.

I’ve written extensively on British soldier servants. Those who enjoyed this article will also like Chapter 8 of my book British Soldiers, American War (Westholme Publishing, 2012), and the following posts on my blog:

Post 1

Post 2

Post 3

Post 4

Post 5

Post 6