In 1779 George Washington moved the Continental Army into New Jersey. He wanted to be within striking distance of New York City but at the same time be able to respond to an attack in or around Philadelphia. He chose Morristown at Jockey Hollow in the Watchung Mountains as his camp and headquarters. To protect the army from a surprise attack by Gen. Clinton’s forces out of New York, he ordered General Alexander, Lord Stirling to put together a plan for a series of signal beacons be built “on conspicuous hills and Mountains, which appear to be judicious and well disposed” on the eastern side of the Watchung Mountains then called the Blue Hills of New Jersey.[1] Stirling was given the assignment because he knew the mountains and lowlands very well, being a gentleman farmer and soldier from nearby Basking Ridge.

Similar beacons had already been built in the Hudson Highlands of New York. The beacons were to serve three purposes: to call out the militia, to indicate the approach direction of the British and to direct the subsequent movements of the militia. Stirling met with the field officers of the militias of Middlesex and Somerset counties and “Setled with them their posts to Assemble at in Case of Alarm” as well as “the Most proper Method & places for Signals.”[2] Washington, aware that he needed permission from the state before building any beacons, wrote to Governor William Livingston. The governor “most heartily approved it,” but because the New Jersey Council-of-Safety Act, passed on September 20, 1777 and extended on June 20, 1778, had expired on October 8, 1778, he needed to set the request before the state’s General Assembly.[3]

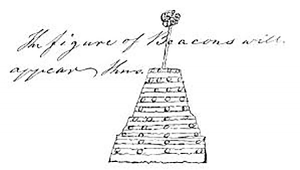

Stirling’s order on how each beacon was to be constructed stated:

Each of the beacons are to be of the following dimensions: at bottom, fourteen feet square, to rise in a pyramidal form to about eighteen or twenty feet high, and then to terminate about six feet square, with a stout sapling in the center of about thirty feet high from the ground. … The following logs to be cut as near the place as possible: twenty logs of fourteen feet long and about one foot diameter; ten logs of about twelve feet long; ten logs of about ten feet long; ten logs of about nine feet long; ten logs of about eight feet long; twenty logs of about seven feet long; twenty logs of about six feet long. He should then sort his longest logs as to diameter, and place the four longest on the ground, parallel to each other, and about three feet apart from each other. He should then place the four next logs in size across these at right angles, and so proceed until all the logs of fourteen feet be placed. Then he is to go on in the same manner with logs of twelve feet long, and when they are all placed, with those of lesser size, till the whole are placed, taking care, as he goes on, to fill the vacancies between the logs with old dry split wood or useless dry rails and brush, not too close, and leaving the fifth tier open for firing and air. In the beginning of his work to place a good stout sapling in the center, with part of its top left, about ten or twelve feet above the whole work. The two upper rows of logs should be fastened in their places with good strong wooden plugs or trunnels.[4]

A total of twenty three beacons were built. The Watchung Mountains are a multi-ridged mountain chain. The first eight beacons were built on the southeastern or first ridge; the remaining fifteen were built on the northeastern or second ridge. They stretched for over forty miles from Somerset to Bergen County.[5] The location of some of the beacons was very specific while others were atop a nondescript hill or mountain near a town.

“Signals on which the militia are immediately to assemble”

Locations described by Baron de Kalb with numbers added for clarity

Beacon #1 “A Longe fire on the Mountain in the rear of Pluckemin”

Beacon #2 “one on the mountain near steak [Steel] Gap”

Beacon #3 “one on the mountain near Mordicas or wayn’s Gap”

Beacon #4 “near Linelons [Lincoln’s] Gap”

Beacon #5 “one near Quibble Town Gap” [at Washington’s Rock Lookout?]

Beacon #6 “on the Hill the road to Baskin-Ridge four miles north of Col. Van Horns”

Beacon #7 “on the Hill toward princetown”

Beacon #8 “one on the Hill in front of Marten Taverns near short hills”

Beacon # 9 “at the point of the mountain [Beacon Hill?] north of Springfeild one mile under the care of Capt. [Isaac] Gillam”

Beacon #10 “on the top of the Hill [Hobart Hill in Summit?] one mile south East of Chatham Bridge under the Care of Capt. [Joseph] Norton ”

Beacon #11 “at [John] Cooper’s Wind Mill on Long Hill at [Col.] Corn[elius] Ludlows”

Beacon #12 “at the point of Kennys Hill at Morristown [Fort Nonsense]”

Beacon #13 “on pidgeon Hill four miles north west of morristown”

Beacon #14 “on Schuylers mountain N. W. of Pluckinin 12 miles”

Beacon #15 “on the Hill 10 miles west of Do.”

Beacon #16 “on the South Point of Cushatunk [Round Hill?]”

Beacon #17 “on the Hill [Prospect Hill?] N. W. of Fleming towns”

Beacon #18 “on the N. W. point of the Southern Hill [Goat Hill?] ”

Beacon #19 “on the Hight of Amwell looking southward”

Beacon #20 “one on princetown looking southward”

Beacon #21 “on the Carter hill in monmouth”

Beacon #22 “on middleton hill”

Beacon #23 “on mount Pleasent”[6]

It took twenty four men, detached from the regiment encamped nearest to the location selected, one day to cut the needed trees and complete the construction. Beacon 1 was built by soldiers under Gen. Henry Knox[7]; Beacons 2 and 6 were built by soldiers under Brig. Gen. William Woolford and Brig. Gen. Charles Scott;[8] Beacons 3, 4, and 5 were built by men under Gen. William Smallwood;[9] Beacon 7 was built by men under Maj. General Arthur St. Clair;[10] and Beacon 8 was built by men under Brig. Gen. Peter Muhlenberg.[11] These were the signal alarms that protected the initial passes into the mountains.

In General DeKalb’s list of the locations of the twenty three beacons he includes the names of two men who were assigned the responsibility of lighting them, Capt. Gillam and Capt. Norton, and suggests that Capt. Van Horn was responsible for a third. Governor William Livingston identifies six more men, Lt. VanDewater (Beacon No. 1), Capt. Sebring (No. 2), Lt. Mackleworth (No. 3), Ensign Van Dorn (No. 4), Lt. Catterlin (No. 5), and Capt. Smalley (No. 6).[12] The homes of DeKalb’s three men were located near their respective beacons. Further research could discover if Livingston’s six men had similar situations.

Rev. Dr. Joseph F. Tuttle wrote a description of what it was like for a sentinel atop a beacon hill :

a Company of armed sentinels was stationed on the crown of Short-hills, This point commanded a view of the entire country East of the mountain, including New York Bay, Staten-island, Newark Bay, Newark, Elizabethtown, Springfield, and, in fact, the entire seaboard in the vicinity of New York, so that the slightest movement of the enemy, in all that wide region, could, without difficulty, be detected. It also commanded a view of the entire region West of the mountain, to the crown of the hills which lie back of Morristown, and extending to Basking-ridge, Pluckamin, and the hills in the vicinity of Middle-brook on the South, and over to Whippany, Montville, Pompton, Ringwood, and, across the State-line, among the mountains of Orange-county, New York, on the North.

On that commanding elevation, which could, itself, be seen on both sides of the Short-hills, over all this wide extent of territory, the means were kept for alarming the inhabitants of the interior, in case of any threatening movements of the enemy, in any direction. A cannon — fired every half-hour, answered this object during the daytime and in very stormy and dark nights; while an immense fire, or beacon-light, answered the end at all other times. A log-house or two, it is believed, with fire-places and accommodations for sleeping, were erected there for the use of the sentinels who, by relieving one another at different intervals, kept careful watch both by day and night — their eyes continually sweeping over all the vast extent of country that lay stretched out like a map before them … When the sentinels discovered any movement of the enemy, of a threatening character, either the alarm-gun was fired or this mass of combustibles was set in a blaze, so that tidings were spread almost instantaneously over the whole region.[13]

Other beacons have been referenced in memoirs, letters, and orders, but this author has not been able to place them in the above twenty-three. They are Kettle Hill in Connecticut Farms, McGee’s Hill in Elizabeth, Warren beacon at Mount Bethel, Gouverneur Mountain in Ringwood, Bottle Hill in Madison, Federal Hill in Pompton, Beacon Hill near Parsippany and Green Pond Mountain.

The cost of building and maintaining a beacon varied because some were built by militias, others by the local citizenry. In Washington’s letter to Governor Livingston on March 23, 1779, he wrote, “the first Eight Signals … I will have erected. About the rest Your Excellency will be pleased to give order, if you approve them.” In the draft manuscript dated the day earlier, the second sentence initially read, “Your Excellency may be able to get others erected by the People of the Country in the Vicinity of them.” On January 8, 1781, it was reported to the New Jersey legislature that there was due to John Webster, for erecting a beacon on the Short Hills, by order of Governor Livingston, the sum of seventeen pounds, seventeen shillings and nine pence; on October 6, of the same year, the sum of eight pounds sixteen shillings was reported due to Captain Joseph Horton, for himself and others employed in building a beacon;[14] and Colonel Sylvanus Seeley, a resident of Chatham, was entitled to the sum of fifty six pounds, eight shillings and nine pence; paid to John Roll for building a beacon on Long Hill, and for six cords of wood.[15]

The Watchung Mountains were a natural fortress; combined with Lord Stirling’s beacons, the mountains became an impregnable line of defense. In June of 1780, two British attempts were made to attack Washington’s encampment at Morristown by sending troops from Staten Island to Elizabethtown Point, New Jersey, and from there through the Hobart Gap in the Watchungs. Both attempts failed largely because New Jersey militia were able to mobilize quickly and swarm to the threatened area. The beacons proved their worth, and the British were never able to dislodge Washington or penetrate his defenses.

[1] Philander D. Chase and William M Ferraro, eds., The Papers of George Washington, Revolutionary War Series, Vol. 19, 15 January – 7 April 1779 (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2009), 555-78.

[2] Ibid., 548.

[3] Ibid., 657-58; Peter Wilson, compl., Acts of the Council of the General Assembly of the State of New Jersey, September 20, 1777(Trenton: Isaac Collins, 1784), Chap. XL: 23; Ibid., Chap. XCI: 53.

[4] Benson John Lossing, The Pictorial Field-book of the Revolution (New York: Harper and Brothers, 1852), 808.

[5] Chase and Ferraro, eds., The Papers of George Washington, 19:577-78.

[6] Ambrose E. Vanderpoel, History of Chatham, New Jersey (New York: Charles

Francis Press, 1921), 137-38; Frédéric, Baron de Kalb to Washington, March 14, 1780, The Founding Era Collection, Founders Early Access; in the Peter Force Transcripts of Washington Papers (Continental Army Returns, No. 36, vol. 3, 119) is a paper marked “No. 2. Signals on which the Militia are immediately to assemble” which locates beacons number 1 through 23.

[7] Chase and Ferraro, eds., The Papers of George Washington, 19:577.

[8] Ibid., 581.

[9] Ibid., 580-81.

[10] Ibid., 580.

[11] Ibid., 581.

[12] Carl Prince, ed., Papers of William Livingston, Vol. 3, Reel 9, Frame 739, Lyon Letter Book (Trenton and New Brunswick, NJ: 1979-1988).

[13] Vanderpoel, History of Chatham, 128-29.

[14] Ibid., 136.

[15] Ibid., 138.

5 Comments

While many anticipate their day of shopping at the Short Hills Mall, the informed traveler will appreciate this informative article. Geography was and remains an essential feature of warfare and knowing high points with unobstructed lines of sight made for a successful system of signal beacons. If only Washington had the terrain feature of Google Maps which serves as an excellent tool. In NJ, driving on 124 after exiting I-78 or I-87 north from Suffern, these land features become very obvious.

Where exactly is Round Hill? If I’m looking at Round Valley, is it the 800 foot plateau at the southeast end of the reservoir, or is it the highest elevation (also 800 feet) on the northeast portion of the reservoir?

The northeast elevation is clearly a “point”, and it could be considered “south” to the primary source if he considered “Cushetunk” to be the longer chunk of mountain. The southeast end, however, while more of a plateau than a point, clearly satisfies the condition of “south point” if he was just going by the southernmost peak. I believe both would be viewable from high elevations NW of Flemington, though it’s tough to say as I imagine in 1777 there were far fewer trees in the area.

These beacon fires have always intrigued me in their simplicity and ingenuity, and little seems to be known of them. I had no idea there was a fire atop Cushetunk, and this is of particular interest to me as I live literally walking distance to there. Thanks for the info!

Between December 1778 and June 1779 Washington and His Army cantoned at Middlebrook, NJ not Morristown. General Alexander headquartered at the Van Horne House in Bridgewater NJ. Washington headquartered at the Wallace House in what is now Somerville, NJ.

Jockey Hollow was the following winter of 1779 -1780

In the winter after Trenton and Princeton (early 1777), Washington and his army were in Morristown, also. Washington stayed in an inn on the Green, while at least some of his troops were camped approximately where Loantaka Brook Park is today. Could #13 be Beacon Hill in Parsippany?

The beacon at Mount Bethel was probably located on the hill behind the former site of the King George Inn (corner of King George and Mountainview Roads) in Warren Township. The site is adjacent to the road to Basking Ridge (King George Road) and is almost approx. four miles north of Col. Van Horne’s house. From this point much of northern Somerset County is visible. Alan A. Siegel, President, Warren Township Historical Society.