A soldier writes his wife:

Mount Independence, June 8, 1777

I heartily embrace the opportunity to write to you, hoping that these will find you and yours in good health as I am now. I have been vary hearty since I left home. I herd last week that you were all well. Mr. Church said Sarah had been sick but had got well again. I would have your write to me if you can. I want to hear how you make out. I have nothing in particular to write to you. June 10th I received your letter yesterday and was very glad to see it. I was down the lake as far as Cumberland Bay last week but we could not see anything. We keep out small scouts but never have seen any but once. There were a party came up to Split Rock but did not stay more than 3 days. By what we herd they will not trouble us this summer. The measles are amongst us. Carpenters has had them. Robert & several others expect to have them soon. The Tories are the greatest trouble we have. They have tried to spread the Small Pox but were found out. Rum is 10/- a Quart Sugar 2/6 per lb. Chees 2/6—tobacco 30 a lb. We have got our bounty. My Dear Wife after my regard to you, I don’t know when I shall see you but would have you do as well as you can. Remember that god is as able to support you now as ever if you trust in him. I shall come home as soon as I can get a chance and so I remain you loving husband till Death.

Acquilla Cleaveland[1]

It is likely that by the time Mercy Cleaveland read this letter, her husband already lay in his grave. Four months earlier, he had enlisted as a private in Benjamin Whitcomb’s Independent Corps of Rangers, a small group of men who functioned as scouts and spies for the Northern Department of the American army.[2] Cleaveland died on June 17, 1777, just one week after finishing his letter, during an Indian ambush of a party of Rangers returning from a scouting mission down the lake.[3] A minor occurrence in the overall history of the American Revolution, this small action has become lost in the myriad events of greater significance. However, judging from the number of letters, diaries, and journals that mention the ambush, it held considerably more significance for Acquilla Cleaveland’s contemporaries. Like all combat, for those directly involved, it held mortal importance.

In early 1777, the American army on Lake Champlain struggled to gather the necessary strength to man its positions. Unlike the previous year when there had been well over ten-thousand men at Mount Independence and Fort Ticonderoga, late spring of 1777 found barely a quarter of that number defending the posts. Two conditions brought on the predicament. To the south, Washington had his own dire problems assembling sufficient numbers to counter the British threat to the areas around Philadelphia and New York. As a result, he had few troops to spare for the Northern Department. Acquilla Cleaveland pointed to the second condition when he wrote that rumors claimed the British did not plan to “trouble us here this summer.” Many soldiers, civilians, and members of Congress felt the British would not mount an invasion out of Canada with the result that minimal effort went into strengthening the department.

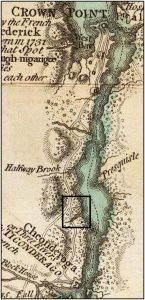

Nevertheless, plans had to be made for defense. Lake Champlain ended twelve miles north of Ticonderoga at Crown Point and the southern extension of the lake, commonly called “the river,” became very narrow. Only a quarter-mile of water separated Ticonderoga from a promontory called Mount Independence on the east shore. Since Ticonderoga had been built by the French to counter an attack from the south, the north-facing Mount offered better protection against an invasion coming up the lake from Canada. However, the Americans had “but 2200 effective, and these ill armed ill cloathed and unaccoutered,” a number and condition considered inadequate for defending the extensive Ticonderoga complex.[4] Expanding the works on the east side of the lake meant taking men from the west side so, to compensate, the old “French Lines” just a few hundred yards out from the fortress became the main line of defense. Outside those lines, use of the old works that had been repaired and the newly-built positions had to be kept to a minimum.

As well as devising a defensive strategy, the American commanders attempted to gain information about British plans by regularly sending scouting parties down the lake. Cleaveland had been on such a mission to Cumberland Bay the week before writing to his wife. Gen. Authur St. Clair commented that “[t]these parties were generally selected from a corps of rangers, who had been accustomed to services of this kind.”[5] St. Clair’s comment referred primarily to two companies commanded by Capt. Benjamin Whitcomb and a smaller company of Vermont men under Capt. Thomas Lee that had been attached to Whitcomb’s corps. The hazards of long distance scouting fell principally to these three companies—a total of less than one hundred men.

American scouting parties in the late spring of 1777 seldom traveled farther down the lake than Cumberland Bay near Plattsburgh, NY. The scouts should have gone beyond that point but intense Indian activity to the north severely restricted the success of such movement and drastically threatened the survival of the scouts. The Indians formed part of the British invasion army that the Americans did not expect to see that summer but which did exist. If the American scouts had been able to approach St. John’s, another 45 miles down the lake, they would have seen the preparations taking place for the British army’s southward movement but those activities remained undiscovered by the American scouts.

The army gathering in Canada represented part of an intricate plan devised by Gen. John Burgoyne who felt that since the heart of the rebellion beat strongest in New England, separating that area of the colonies from the rest would cause the rebellion to wither and die. To accomplish this dissection, he proposed that one force move up the Hudson River from New York City with Albany, New York, as the objective. A second force with the same objective would come from the west via the Mohawk River. The plan would be completed by a third force, under his command moving south out of Canada, up Lakes Champlain and George to the headwaters of the Hudson River, and then follow that river down to Albany. The army gathering under Burgoyne included approximately 9,000 British and German regulars, French-Canadians, loyalists, and Indians from several communities including St. Regis, Sault St. Louis, Lake of the Two Mountains, and St. Francis.[6]

The number of Indians with Burgoyne varied almost on a daily basis, but he expected to have 400-500 accompanying him. Most British officers regarded them with mixed feelings: “The Indians are cunning and Treacherous, more remarkable for rapid marches and sudden attacks than Courage.”[7] The British did see some value in their methods and Burgoyne used them as a screen to sweep up anyone who might observe his army. He also used them in the same manner as Whitcomb’s Rangers served the Americans—as long-range scouts. Lt. Thomas Anburey, an officer with Burgoyne, echoed St. Clair’s comments about Whitcomb’s Rangers when he said that the Indians “were of vast service in foraging and scouting parties, it being suited to their manner.”[8] It was a party of Mohawks from Sault St. Louis, an Indian settlement also called Caughnawaga west of Montreal, which brought about the actions on Tuesday, June 17, 1777.

On that day, with pleasant weather and little expectation of trouble from the British in Canada, the American camp at Ticonderoga had a relaxed attitude.[9] Around noon, the calm atmosphere changed dramatically when the long roll of the drums signaled a call to arms. The alarm had been occasioned by “two Men taken and two killed by a Party of Indians who had concealed themselves in the Bushes near our out Guards, and rushed suddenly upon some unarmed Men who had strolled out a fishing.”[10] These men, from Hale’s New Hampshire regiment, had gone out along the road between the French lines and the mills on the La Chute River.[11] When they had walked only about one hundred rods (about a quarter of a mile) from the lines where a thousand men sat encamped, the Indians fell upon them.[12] Within moments, the Indians had completed their bloody work, dragged their prisoners into the woods, and begun their trek back to Canada.

The attack caught the American camp completely by surprise and assembling the pursuit party took some time. In addition to the lack of a party already under arms at the time of the attack, the Americans held the same opinions about fighting Indians in the woods as did the British and the men felt a certain amount of reluctance to chase an unknown number of them through wooded terrain. By the time the pursuit finally left the camp, the Indians had an insurmountable head start and the Americans could not find them. According to Nathan Brown, the Americans learned a lesson from this incident: “I believe that the officers are all vare much Disapointed and will not tary after them again.”[13]

The Indians knew that they had caused considerable confusion and that the Americans did, indeed, “tary after them.” They certainly did not feel, as one American claimed, “pushed to that degree that they flung away there packs and knives to facilitate there escape.”[14] Soldiers, and Indians, commonly took off their packs before engaging the enemy in order to allow for easier movement, particularly in the woods. The Indians may have taken theirs off before attacking the fishermen but they certainly removed their packs a few miles north of Ticonderoga on their return to Canada.

The attack on the men outside the American defenses did not end the fighting for that day. Jabez Colton wrote a friend that “[s]oon after this a Small Scout of our men returning home commanded by a Leutenant, fell into an Ambuscade of these Indians.”[15] The Indians had successfully raided the front door of the American positions and now, on their way back north, they discovered another party coming towards them from the direction of Crown Point. Since close pursuit from Ticonderoga did not materialize the Indians prepared for more battle.

The Indians set up their ambush around one o’clock in the afternoon.[16] They chose a place called Taylor’s Creek about halfway between Ticonderoga and Crown Point where the approaching party would be down in the bed of the waterway and paying more attention to crossing the creek than to their surroundings.[17] The Indians numbered around thirty. Moving into the ambush was a group less than half that size. Under the command of Lt. Nathan Taylor, at 22, the youngest officer in Whitcomb’s Rangers, the American party included Acquilla Cleveland and a few other men from Whitcomb’s Rangers accompanied by some volunteers from other regiments—a total of fourteen men. With the approaching party outnumbered, unsuspecting, and distracted by crossing a stream, the Indians must have felt confident of another success.

The party of Rangers certainly felt relieved to be within a few miles of Ticonderoga and their camp on Mount Independence. Earlier, they had passed by the American outpost at Crown Point and they would be home within one or two hours. They would have felt secure now that the most dangerous part of the mission had passed. With the Indians well hidden the two parties “were within ten steps of each other” when the Indians triggered the ambush.[18]

The Indians did not fire upon the scouting party without warning. Instead, “[t]he Indians Sprung up & ordered them To Surrender.”[19] One Indian addressed the Rangers using the word “Sago.”[20] Although the word had no direct English equivalent, “Sago” did not constitute a threat but rather carried the essence of’ a greeting one would extend to a friend.[21] Did this Indian think the Rangers were a loyalist party? Did he suppose that the Rangers could be fooled into thinking the Indians sided with the American cause and thereby trick them into an easy capture? Was he actually sympathetic to the American cause and trying to warn them? The men of the scouting party did not care. All they knew was that a strange Indian had suddenly appeared very close to them in the wilderness and Taylor immediately ordered the men to fire.

The reaction surprised the Indians “so thay mad Very wild fires on owre men a pritey warm scurmidge Ensued for a few minets.”[22] Outnumbered and nearly surrounded, Taylor and the rest of the party soon realized that they had to fight their way out. Following one of the classic military maneuvers with which to counter an ambush, Taylor and his men attacked a weak point in the Indians’ position. They broke through the encirclement and, expecting hot pursuit by the Indians, fled toward Ticonderoga: “[O]ne of our men was a Bliged to swim through the Lack.”[23] Although the Indians had the Rangers outnumbered and on the run, they did not pursue them back towards Ticonderoga. They knew that, by now, the Americans at Ticonderoga had a party after them and the noise of the musket fire had told that party just where to find them. Their confidence now shaken by the hard fighting of the Rangers, the Indians collected their casualties and continued down the lake leaving their packs to be found later by the Americans.

Reports of American casualties for the day varied. Lieutenant Taylor received a wound in the left shoulder. The ball entered near the top of his shoulder, ran across his shoulder blade and came out near his backbone.[24] He continued to serve in Whitcomb’s Rangers for two-and-a-half more years until he finally had to resign his commission due to lingering effects of the wound. An unnamed soldier received a wound in the head.[25] Others certainly received wounds during the fight but, at this time, their names have not been discovered. Two men died in the ambush—one being Acquilla Cleaveland. Records indicate three men of Caleb Robison’s Company in Hale’s Regiment—Joseph Harris, Moses Copps, and Samuel Smith—all died that day. Whether they suffered their fate near the French Lines at Ticonderoga or in the ambush has not been determined. Four other men—Israel Woodbury and Thomas Creighton of Hale’s regiment, Edward Wells of Poor’s regiment, and William Presson of Scammell’s regiment—are all listed as missing at that time. Like those killed, it has not been determined if they became prisoners during the raid or the ambush.

The number of Indian dead and wounded remains more of a mystery. In the confusion of fighting in the woods, the combatants could not tell if their shots reached their targets but Taylor and his men knew that they had killed at least one Indian and suspected that they had inflicted other casualties. When a burial party went back the next day, they “found one Indian dead lying between two logs with his Powder horn and a Bullet Pouch. … Our men saw as they supposed signs of one or two more that were killed and draged into the 1ake.”[26] Further, although the Indians succeeded in disguising how many casualties they had suffered by carrying off their dead, the Americans felt that “it is probable they must have met with some as they were within ten steps of each other.”[27] Even with a smooth-bore musket, it is hard to miss a target at that range and the Americans often loaded with buck and ball which would increase the likelihood of their fire having an effect.[28]

If the Americans could believe the accounts given by the Indians to their British commanders, however, the Indians did not suffer many casualties in the action. The British officer in charge of the Indian scouting parties, Lieutenant Scott, sent a report to Brigadier General Fraser telling him that one of the scouting parties “had met with a small party of the Enemy about 14 or 15 in Numbers, of whom his people killed 4, and took 4 prisoners; the Indians had one killed and one wounded; … They fell in with them some where near Ticonderoga.”[29] The British accurately reported the size of the American party but the numbers of casualties and captured differed from American reports. Lieutenant Scott may have included in his report those killed and taken prisoner near the French Lines or at some other time and place in the Indians’ movements. Even with unclear casualty figures, the day’s events appeared to have been a victory for the Indians.

In spite of the danger of the Indians still being in the area, Whitcomb and some of his men returned to the scene of the ambush the next day. They found and buried the two dead Americans, one of whom had been scalped by the Indians before they left the scene.[30] The Rangers returned to Mount Independence the next day after performing their melancholy duty.[31]

If there existed any sense of triumph for the Americans to take from these occurrences, it was that the Rangers had killed at least one Indian and wounded some others “so that our injuries are not altogether unavenged.”[32] Benjamin Whitcomb made the best of the situation: “Thursday. This day pleasant wind variable Capt Whitcomb returns from Scout brings a Grand Scalp of the Coynawago’s.”[33] A touch of the excitement (and possible embellishment) the taking of this scalp brought to the American camp can be read in the lines, “and to our satisfaction the body of the Indian Chief with all his Ornaments on, of which they striped him, as well as his Scalp which were carried in triumph through our Camp.”[34]

With the Indians getting so close to the American lines and a scouting party being ambushed such a short distance from home, many in the camps at Mount Independence and Fort Ticonderoga began to worry about the British plans. Did they, after all the rumors, intend to move up the lake? From that point on, St. Clair sent out more scouts than before and over a wider area: “I had all the ground between this and Crown-point, from the Lake some distance over the mountains, well examined yesterday with a heavy scout, but they discovered no enemy, nor appearance of any.”[35] Although this particular scout had nothing to report, it went only as far north as Crown Point. On the 28th, a smaller party went farther north:

My scout, on which I depended much for intelligence. is not yet returned, nor I fear ever will now. It consisted of three men only, the best of Whitcomb’s people, and picked out by him for the purpose. The woods are so full of Indians that it is difficult for parties to get through.[36]

By the time of this scout, the army under Burgoyne had advanced several miles up the lake and had his Indians scouring the woods to prevent American scouting parties from discovering the move. Although the Americans apparently did not get captured or killed, they did not return in time to give St. Clair any information that could save the positions around Mount Independence and Ticonderoga.[37]

Four days after the action at Taylor’s Creek, on June 21, Burgoyne made a speech to the Indians in which he complimented them and offered a reward for bringing in prisoners. At the same time he forbade their scalping any but the dead. Did the action of the 17th have some influence on Burgoyne’s speech? Offering the Indians a reward for prisoners minimized unnecessary killing such as that which had happened to the unlucky unarmed fishermen near the French Lines. Burgoyne knew the coming campaign promised to be long and difficult and he felt it best to reinforce his expectations of the Indians before events such as those of the 17th became more frequent and the risk of unwanted and unnecessary actions became too high.

The events on June 17,1777, proved to be the first in a series of actions which would cost the lives of many people, culminate in the battles at Saratoga, and alter the course of world history by helping secure the birth of the United States. Innumerable people over the interceding centuries have been aware of these results but what has been lost in the haze of history (but certainly remembered by Mercy Cleaveland—she still had her husband’s letter over sixty years later) is that somewhere near a woodland creek between Ticonderoga and Crown Point are the graves of a few, including that of Mercy’s husband, who died early in that struggle.

[1] Acquilla Cleaveland, letter to wife Mercy, June 8-10, 1777; pension application of Mercy Cleaveland, page 25; Revolutionary War Pension and Bounty-Land Warrant Application Files (National Archives and Records Administration, M804, roll 574). Hereafter referred to as “Pension Files.”

[2] The Northern Department of the army consisted of most of New York and Vermont.

[3] Lakes Champlain and George flow north so anyone going from that area to Canada would go “down” the lake.

[4] Arthur St. Clair, letter to James Wilson, June 18, 1777; vol. 2, box 10, James Wilson papers (Collection 721, The Historical Society of Pennsylvania).

[5] “Proceedings of a General Court-Martial, … for the Trial of Major General Arthur St. Clair, August 25, 1778,” in Collections of the New-York Historical Society for the Year 1880 (New York, 1881), 78. Hereafter cited as “Court-Martial of Gen. St. Clair.”

[6] George G.F. Stanley, ed., For Want of a Horse, (Sackville, New Brunswick, Canada: Tribune Press, 1961), 98n.

[7] James Murray Hadden, Hadden’s Journal and Orderly Books, Horatio Rogers, ed., (Albany, NY: J. Munsell’s Sons, 1884), 15.

[8] Thomas Anburey, Travels Through the Interior Parts of America; in a Series of Letters by an Officer (London: W. Lane, 1789), vol. I, 425 (Letter XXXIX).

[9] Moses Greenleaf, “’Breakfast on Chocolate:’ The Diary of Moses Greenleaf, 1777,” Donald Wickman, ed., The Bulletin of the Fort Ticonderoga Museum, vol. XV, no. 6 (1997), 494.

[10] St. Clair to Wilson.

[11] Henry B. Livingston, Ticonderoga, to William Livingston, June 21, 1777, letter, Livingston Papers, Massachusetts Historical Society, Boston.

[12] Nathan Hale, Ticonderoga, to Abigail Hale, Rindge, NH, letter, June 21, 1777, Hale Family Papers, 1698-1918, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.

[13] Nathan Brown, Mount Independence, to John Dudley, Raymond, NH, letter, June 23, 1777, Dudley Papers, File 1, document 3-b, New Hampshire Historical Society, Concord, NH.

[14] Ebenezer Stevens, Ticonderoga, to Samuel Philip Savage (President of the Board or War), letter, June 24, 1777, Massachusetts Historical Society, Boston.

[15] Jabez Colton, Mount Independence, to Reverend Dr. Stephen Williams, Longmeadow, MA, letter, June 19, 1777, Fort Ticonderoga Collections [FTA M#-1998].

[16] Greenleaf, 494.

[17] Surgeon’s report, pension application of Nathan Taylor, “Pension Files,” reel 2350, image 565. Although a creek by that name does not show on contemporary maps, there is a brook named Halfway Brook (shown as Grant’s Creek on many current maps) on William Brassier’s 1762 map, A survey of Lake Champlain, including Lake George. It is likely this is the area where the action occurred. In further support of this is a contemporary comment that the lake was almost two miles wide at the point where the ambush occurred. Inspection of the lake between the two forts shows that although much of that stretch of the waterway is relatively narrow, it does widen considerably in the area where Halfway Brook enters the lake.

[18] St. Clair to Wilson.

[19] Hale to Hale.

[20] Colton to Williams.

[21] Author’s conversation with George Larrabee, expert on northeastern Native Peoples.

[22] Hale to Hale.

[23] Brown to Dudley.

[24] Surgeon’s report, Nathan Taylor pension application.

[25] Hale to Hale; Colton to Williams.

[26] Ibid.

[27] St. Clair to Wilson.

[28] “Buck and ball” is nine or twelve smaller buck shot loaded on top of the normal full-size ball.

[29] Stanley, 98.

[30] No information has come to light as to how or when in the skirmish poor Cleaveland died or whether or not his body suffered from the scalping knife. Clues exist for some of the names of the other men taken and killed that day but who was involved where and what happened to whom has not yet been verified.

[31] Colton to Williams.

[32] St. Clair to Wilson.

[33] Greenleaf, p. 495.

[34] Stevens to Savage. No other sources claim the dead Indian to be a chief. If he had been a chief, it would seem that the British reports of the incident would have included that bit of information assuming, of course, that the other Indians told him that bit of knowledge. Another question is why did the Indians leave this body instead of taking it away with them as was their usual custom? It seems as though they would particularly have wanted to take the body of a chief with them. Did they simply not find the body? According to Whitcomb’s report, his burial party found the body near the dead Americans and they apparently found it with little trouble. The Indians took the time to scalp at least one of the dead Americans and they took the time to carry off their other casualties. Why not this one? If this Indian had been the one to stand up and say ”Sago” to the Rangers, could it have been an intentional action by the rest of the Indians to leave this body and thereby condemn his soul to eternal disgrace?

[35] Court-Martial of Gen. St. Clair, 21.

[36] Ibid., 122.

[37] Which individuals went on this scout is not known but the rolls for the companies under Whitcomb’s command do not show any casualties around that time. Abel Rice, a sergeant in Whitcomb’s Rangers, may have been one of those men. He returned to Ticonderoga from a scouting mission to find the British flag flying over the fort! Imagine the shock—instead of relaxing with his friends, he now had to travel through an unknown number of miles of enemy territory in search of an army the whereabouts of which he had no idea. He eventually found his way through the enemy lines without incident and rejoined the rest of the Rangers.

14 Comments

Very nicely done. Solid research, Michael.

Thanks, Will. Your comments are greatly appreciated. Since Whitcomb’s Rangers is my reenactment unit, I did the work–at least in part–as a “labor of love” and, to a greater extent, out of respect for their service and commitment to the newly united states.

Yesterday was the 150th anniversary of the Lincoln assassination, so the New York Times published an article about the non-academic (I refuse to say “amateur”) historians who devote their time to John Wilkes Booth. They were originally called “Boothies” as a slight insult by the Lincoln scholars, but now it has become a term of affection because they have dug up so much on Booth for which professionals had not bothered to look. An example: people put pennies, with Lincoln facing up, on Booth’s grave in Baltimore, to symbolically keep him buried.

So we are not alone!

Excellent piece, Mike! Finding the relevant correspondence must have taken considerable sleuthing! I recall that Brigadier Simon Fraser also discusses the reports he received about the incident in his post-Battle of Hubbardton letter, but he may have been simply relating the information he got from Stanley. I don’t remember offhand what it says about casualties, but I believe they were mentioned. Very poignant tale about the hapless Acquilla Cleaveland!

There are British documents, including Fraser’s, that can be interpreted as referring to this incident but they are, as you say, based on the same second-hand information. On top of that, the Indians pretty much blended all their activities from that mission into one story. Because the Brit sources did not add to the account, I did not bother to include much from them.

Mike, a thoroughly enjoyable article providing a rich texture of what life was like in the Champlain Valley in 1777. You provide another example of the importance of Intel and geography on military outcomes.

Given that Burgoyne’s Indians helped galvanize the patriots resistance, I wonder if he would have been better off without them. South of Ft TI, Native Americans provided little military value including abandoning the fight at the battle of Bennington.

Thanks for your comments, Gene. It means a lot when the scholars on this site take the time to provide feedback.

It is the story of the person rather than the event that draws my interest. I want to learn about the details of what they experienced and, because of that, I tend to build my research and writings from the bottom up. While that may draw me away from grand analytical historiography, I think it gives readers a more personal connection to whatever the topic is.

With regard to Burgoyne’s Indians, even he eventually wondered the same as you. Some form of the question, “Would I have been better off without them?” crossed his mind early in the campaign. The Indians did adequate service until the death of Jane McCrae and Burgoyne’s meeting with them on August 4 (I believe that’s the date–it’s well before Bennington in any case). Following that, large numbers began leaving and returning to Canada every day. On top of diminishing numbers, their one great advantage–the American fear of them–had begun to diminish and the Indians found themselves overmatched by enemy irregulars. The campaign’s Indian situation is covered in some detail in Burgoyne’s “State of the Expedition,” the report of his hearings before the House of Commons.

Mike, I like your bottoms up approach to interpreting Revolutionary Vermont. It helps the reader more accurately understand what people in the Champlain Valley were experiencing and thinking. Grand, sweeping generalities can neglect the personal motivations and experiences which led to collective actions. As you point out Indian activity limited American scouting down the lake and also likely weighed heavily on Acquilla Cleaveland’s mind for the safety of his wife. It had to be fearful times for all Champlain Valley residents. The matter of fact nature in which Cleaveland raises the specter of death is telling.

Gene, I agree with Mike that much depends upon what portion of Burgoyne’s campaign you are looking at. Prior to July 3, 1777, the role of the Indians was potentially decisive in that, as Mike mentions in his article, they effectively suppressed scouting efforts and prevented the Americans from assessing the magnitude of the threat to their post at Fort Ticonderoga/Mount Independence until Burgoyne was literally at their doorstep. Had Burgoyne been able to capitalize on the spectacular strategic surprise he had attained by then capturing St. Clair’s army whole, the role of the Indians would have been the key.

Ron, very interesting idea about Burgoyne not being able to capitalize on his strategic surprise enabled by the Indian activity screening his army. I also wonder if there were mismatched goals and expectations. Burgoyne employed the Indians in a conventional fashion to support his massive invasion and the Indians were seeking quick victories and easy plunder. When it became clear that the Americans would put up a spirited fight, the Indians returned to Canada unwilling to risk heavy casualties.

There’s more to the Indian departure than an American spirited defense. Hubbardton, while a victory for the Crown forces, had a high cost for Burgoyne and friends and showed them the kind of fight the Americans had in them. Burgoyne’s desire for control of the Indians (limited scalping), the deteriorating state of his army (diminishing spirit), and the American scorched-earth retreat (limited plunder) all played a part. Top it off with supplies running low by early August creating a distinct possibility of going on reduced rations in the near future. All these factors increased the motivation for departure. The American victory at Bennington (a spirited action by the Americans, yes, but mostly a victory brought about by overwhelming numbers and the timely arrival of Warner’s fresh troops) appears to have been the final straw for many Indians–they announced their intent to leave shortly after that and most did just that. They saw the writing on the wall–or, in this case, in the mud.

Gene: I have given considerable thought to Burgoyne’s actions as he began to invest Fort Ti/Mount Independence, and I suspect that historians have missed some key points about his strategy. We know that Burgoyne was aware before he left Canada that Howe was not going to act in a coordinated manner with his campaign, and there is considerable evidence from Burgoyne’s correspondence that he also knew that he had an insufficient supply train for a lengthy sustained campaign inland. Given these realities, it would stand to reason that Burgoyne would have given a very high priority to achieving a decisive victory at the outset, and, indeed, Simon Fraser confirms this in a letter he wrote shortly after Hubbardton, saying that in the days prior to the American retreat, Burgoyne was obsessed with cutting the army off and capturing it, ordering his forces forward agressively (to the alarm of his subordinates) at the merest hint of any move that might suggest a retreat. The fact that the Americans were able to successfully retreat in the face of a very determined effort to prevent it is noteworthy, and has been virtually overlooked by historians. Once the American army escaped, I think Burgoyne knew the odds of success were now stacked against him, but the capture of a huge amount of American supplies at Fort Ti/Mount Independence, coupled with hubris and likely a fear of the political consequences if he called the campaign to a halt at that point, served to draw Burgoyne onto a path that eventually doomed his army.

Yup.

A very informative and detailed accounting of the events transpiring on June 17th, citing some interesting sources of which I had not previously been aware. I am curious in regards to what, during the course of your research on this subject, however, led you to conclude that the war party under Captain Scott’s command were from the mission of Caughnawaga, other than the reference made near the end of the article to Captain Whitcomb’s having taken the “Grand Scalp of the Coynawago’s” upon his return to the scene of Taylor’s ambush the following day. It had been my understanding that Lieutenant Thomas Scott of the 24th Regiment had been appointed as the British officer responsible for the Lake of Two Mountains mission during the reorganization of the British Indian Department occurring in December of 1776. Stanley’s Journal references the arrival of Captain Scott and a party of 70 natives from the Lake of Two Mountains mission at the Bouquet River encampment on June 14th, which were the first to arrive at that location. In Fraser’s letter to Robinson, the general stated that once Indians had arrived, he dispatched a scout towards Ticonderoga to try to take a couple prisoners as he had very little intelligence regarding the enemy up until then, and, again, Stanley’s Journal confirms their deployment to Split Rock the following day, which would seem to support the contention that the war party was from the Lake of Two Mountains not Caughnawaga mission. Captain Alexander Fraser, Lieutenant Richard Houghton of the 53rd Regiment (British appointee of the Caughnawaga mission), and Lieutenant James Wright of the 9th Regiment (British appointee of the St. Francois mission) with 230 Indians from the Caughnawaga and St. Francis missions did not arrive at the Bouquet River encampment until the evening of June 17th, or after the events at Ticonderoga had already taken place. Any insight into a better understanding of this aspect of the subject matter would be warmly appreciated.