It is not by coincidence that almost every battle of the American Revolution was fought along a road. Everything an army needed was carried on wagons which could only travel on roads. While a detachment of soldiers could operate independently for a short time by carrying their provisions or foraging for food, the movement of an army with horse-drawn artillery and cavalry required tons of provisions every day to feed the men and horses along with wagon loads of ammunition, tents, medical supplies, entrenching tools and an array of services including a portable blacksmith shop complete with anvils and bellows.[1]

Soon after taking command of the British Army in America, Gen. William Howe wrote the Treasury in London requesting that they purchase a wagon train for him in England in anticipation of his 1776 campaign aimed at capturing New York City.[2] Howe realized that he needed wagons and horses to move inland to suppress the rebels from his base at New York. The Treasury approved Howe’s request and employed Francis Rush Clark to supervise the project. Clark was a civilian who was recommended for the position by Parliament member John Strutt based on Clark’s expertise in the construction and maintenance of wagons and wagon harnesses in addition to being experienced in caring for horses. Clark was hired in the spring of 1776 with the title of, “Inspector and Superintendent of the Provisions Train of Horses and Waggons attending our army in North America.”[3] Things went badly for Clark from the outset of his assignment and his story is an example of the disorganization and corruption which plagued both the British and Continental armies during the war.

Clark purchased sturdy freight wagons and work horses in England which were dispersed throughout a transport fleet that sailed from the English port of Plymouth on July 20, 1776. The slow moving convoy took four months to cross the Atlantic and according to Clark, the long voyage combined with unseasonably hot weather killed a great number of horses.[4]

Clark’s wagon train reached British occupied New York in mid-November 1776. He landed his wagons and his remaining enfeebled horses which he intended to nurse back to good health. Finding stables for Clark’s horses in New York was a problem which never materialized as the British Army quartermaster general immediately appropriated Clark’s horses to meet the pressing needs of the army.[5] Acting under Howe’s orders, Gen. Charles Cornwallis invaded New Jersey on November 20 and every available horse and wagon was needed to keep his army supplied.

Clark’s wagons were a different matter. He discovered after arriving in New York that they were too heavy for the crude American roads. Clark showed General Howe that he could reduce the weight of his government owned wagons from 1,350 pounds to 850 pounds while maintaining their strength and hauling capacity. In addition he explained that the wagons the army was hiring at the time from Loyalist farmers on Long Island (Clark called them “Country Waggons”) were flimsy with weak harnesses made of “slight leather & ropes instead of chains” that snapped under the strain of pulling heavy loads and no canvas tops to protect food stuffs or shelter the sick and wounded. “Nothing of this sort could be constructed more unfit for any Army,” Clark wrote to his superiors in London. “They are so slight”, Clark said, “as to be in perpetually in want of repair.” He drew a sketch of a “Country Waggon” which he included in one of his reports to the Treasury to illustrate their flimsy construction.[6]

Clark was capable but he had no money or authority to dictate policy as it was assumed that he could count on the cooperation of the army. Apparently Clark, who was a civilian unfamiliar with army routine, was also obsessive about wagons. Howe quickly grew tired of Clark and his boring ceaseless chatter that the army should own its own wagons and horses instead of renting them from local farmers.

Howe’s quartermaster department continued to hire transport on a short term basis through the winter of 1776-1777. However, this casual system proved unreliable and in the spring of 1777, Howe ordered the quartermaster department to lease a wagon train on long term basis while Clark’s government owned wagons sat idle. The army’s policy of hiring wagons and horses remained in effect until the late spring of 1782. During this period, it averaged 730 wagons and 1,958 horses for the army based at New York with smaller wagon trains in other British held territories.[7]

The army’s hire system opened the opportunity for profiteering on a scale which one historian described as “an attack on the public treasury.”[8] The assault was led by army officers working in the quartermaster department. Their scheme was to use threats and intimidation to buy wagons and horses from civilians at low prices. Then they turned around and leased them to the military at the generous daily rate being offered by the army and pocketing the difference. If a wagon was damaged beyond repair or captured all the better as the owner (a British officer or his proxy) was paid a generous sum for his loss. Compensation was also paid for horses which died or were captured while in military service.

It is estimated that the army’s hired wagon train cost approximately £128,000 per year from 1777 to 1781 or about 30 million dollars a year in today’s U.S. dollars.[9] Aware of the situation, Clark reported that “private emolument has been more attended to than publick good.”[10]

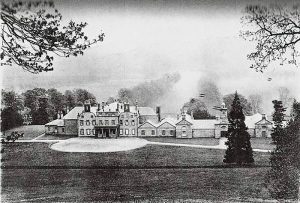

The leading participants in the wagon train scheme were Sir William Erskine, the Quartermaster General and his three senior deputies; Col. William Shirreff, Maj. Henry Bruen and Capt. Archibald Robertson. It is difficult to know how much money these officers made from their manipulations but after resigning from the army in 1779, Col. Shirreff purchased an estate near Southampton, England. Major Bruen retired in 1783 and bought a mansion called Oak Park in County Carlow in his native Ireland. Robertson was commissioned a lieutenant in 1763; captain in 1775 and major in 1780.[11] He was appointed a deputy quartermaster in 1780. Before retiring in 1783, he was to able purchase a lieutenant colonelcy for cash which gave him a handsome half-pay allowance for the rest of his life. Robertson then returned to Scotland where he married the daughter of a Lord, and paid £35,000 for a 20,000 acre estate named Lawyers in Ayrshire, Scotland. He lived the life of a gentleman on his estate for the next 30 years.[12]

How did these men manage to accumulate fortunes with an astute observer like Francis Rush Clark sending reports to the Treasury exposing their conspiracy? The answer is that the Treasury was overwhelmed by the complexities of supplying the British army in America. It was understaffed by civilians operating 3,000 miles from the war zone. Adding to the problem was that various army branches and private contractors were competing for wagons and horses resulting in erratic prices that were difficult to audit. Periodic inquiries into the enormous cost of army transport was buried in diatribe by officers who concealed their ownership of the wagon train and explaining that leasing transport had “…ever been the practice in America since General Braddock’s time.”[13] As for Clark, he wound up as a clerk in the quartermaster department.

Today’s U.S. Army Quartermaster officers study the logistical problems the British army faced in the Revolutionary War which is relevant to today’s American forces fighting far from home in unfriendly territory. One Quartermaster study of the period concluded; “… the lack of sufficient reserve supplies, insufficient transportation, widespread corruption, and the lack of a coherent strategy…ensured British failure in the American Revolution.”[14] [15]

[1]An army of 20,000 men consumed thirty-three tons of food in one day. Since a four-horse wagon could carry about a ton, an army of that size on a campaign required at least thirty-three wagons and 132 horses (33 wagons, 4 horses each) to provide the troops with food per day. This was in addition to feed for the horses of the cavalry and artillery companies plus food for the horses pulling the wagons. At times oxen were used instead of horses to pull wagons and artillery.

[2]In the eighteenth century the Treasury was the largest department of the English government and exercised general financial control over the operations of the entire government. It was administered by The Treasury Board, which consisted of the First Lord, the Chancellor of the Exchequer, and three junior lords. Howe’s wagon train was a costly expense which required Treasury approval and funding. See Thomas C. Barrow, Trade & Empire (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1967), 109.

[3]The Papers of Francis Rush Clark (17 November 1776 to 25 October 1779). Sol Feinstone Collection, David Library of the American Revolution (on deposit at the American Philosophical Society).

[4]Ibid. Clark stated that he left England with 845 horses. 367 of them died during the long voyage and 59 others succumbed shortly after reaching New York.

[5]British logistical practices at the time of the American Revolution divided supervisory responsibilities between a civilian Commissary General of Stores and Provisions, concerned with foodstuffs and the procurement and storage of general supplies and a military Quartermaster General responsible for transportation, forage, camps and the movement of troops. A separate logistical branch handled munitions. The Quartermaster General is identified as a senior officer in the army and should be a man of great judgment and experience. See Captain George Smith, An Universal Military Dictionary (London: Printed for J. Millan, 1779), 219 and Robert K. Wright, Jr., The Continental Army (Washington, D.C.: Center of Military History United States Army, 1983), 36.

Logistics in military usage means the aspect of military science dealing with the procurement, maintenance and transportation of military material, facilities and personnel. The word did not exist at the time of the American Revolution. The earliest known use of the word logistics is in an 1810 book titled The Elements of The Science of War.

[6]The Papers of Francis Rush Clark, Sol Feinstone Collection.

[7]Edward E. Curtis, The Organization of the British Army in the American Revolution (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1926), 139.

[8]R. Arthur Bowler, Logistics and the Failure of the British Army in America 1775-1783 (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1975), 182.

[9]Bowler, Logistics and the Failure of the British Army in America, 183.

[10]Richard M. Ketchum, Saratoga Turning Point of America’s Revolutionary War (New York: Henry Holt and Company, 1997), 262.

[11]Harry Miller Lydenberg, editor, Archibald Robertson His Diaries and Sketches in America (New York: The New York Public Library, 1930), 7.

[12]Ibid., 32. Robertson was born in Scotland and was educated as a youth by local tutors. He was a promising student in mathematics and physics but there is no record that he graduated or attended college. Robertson joined the royal engineers at the age of 15 on March 17th, 1759. It was an honorable but unfashionable appointment indicating that neither he nor his family were wealthy or influential. His slow promotions after joining the army are a further clue to his middling finances and social standing.

[13]This quote is attributed to British General Darlrymple who served as Quartermaster General in one point during the war. See Bowler, Logistics and the Failure of the British Army in America, 185.

[14]Major Eric A. McCoy, “The Impact of Logistics on the British Defeat in the Revolutionary War,” U.S. Army Sustainment Magazine, Vol. 44, Issue 5 (September-October 2012).

[15]There is a seemingly routine quote in the Papers of Francis Rush Clark of interest. The entry reads, “The Army moved the 13th June [1777] in the evening. I saw them clear of [New] Brunswick. The flat bottomed boats and carriages did not go with them. I therefore deposited the harness in a storehouse…and returned to New York the 14th at Night.”

What Clark is referring to is Howe’s June 1777 foray into central New Jersey from his base at New Brunswick to bring Washington’s army into a general engagement. Howe’s objective was Philadelphia, the principal city in the colonies and the seat of the rebel government. The fastest way to reach Philadelphia was through New Jersey but Howe had to first defeat the main American army which was holed-up in the Watchung Mountains which were a short march from New Brunswick. Howe knew that Washington would fight a partisan war from his mountain stronghold ambushing British troops and cutting Howe’s supply lines.

Apparently Howe was serious about attacking Philadelphia through New Jersey in June 1777 as Clark’s comment proves that his army was accompanied by wagon loads of boats which Howe’s engineers could use to construct a pontoon bridge across the Delaware River.

Unable to bring Washington’s army into a general engagement in New Jersey, Howe returned to New York and boarded his army onto ships to attack Philadelphia from the south.

3 Comments

Another good look at this scandal is in Thomas Flexner’s biography of States Dyckman. Dyckman had to go to England after the war and blackmail some of the officers to get his share.

I am glad to see this article with its illustration and sizes. Now I will have better answers to the questions people ask us at Hale Byrnes House.

40 wagon loads of grain and flour were taken from Daniel Byrne’s mill in Delaware by Washington’s troops to feed the soldiers and I have always imagined Byrnes standing out front staring down the road, watching the caravan.

Thank you so much for your good work.

Erna Risch’s history of Revolutionary War logistics in her online book, “Supplying Washington’s Army,” elaborates in detail about the subject of transportation in the Revolutionary War. For instance, Massachusetts responded to Washington’s request for wagons to transport his army from Boston to New York City in 1776 by providing him with 300 wagons. The problem with starvation at Valley Forge was basically a transportation problem. There was food and forage in the magazines surrounding the British in New York City but no plan to transport them to Valley Forge. Erna Risch was the historian (Univ. of Chicago Ph.D. in 1940) for the Quartermaster Department for the U.S. Army, well-qualified for this work.