Captain Jonathan Carver’s Reconnaissance

Captain Jonathan Carver was hired in August 1766 as a surveyor and draughtsman by Major Robert Rogers, the newly appointed governor-commandant of British Fort Michilimackinac. Rogers instructed Carver to familiarize himself with the northern Mississippi River basin and western Lake Superior region’s geography, prepare a map of the area and then, if directed, join an exploration team on a westward trek to discover a route to the Pacific Ocean.

Shortly after Carver’s return to Michilimackinac in late August 1767, Rogers was arrested on a charge of treason and taken to Montreal. Although Carver was left unpaid for his year’s work, he spent the ensuing winter and early spring at the fort working on his journal and survey plans before returning to his home near Boston, Massachusetts. Carver’s explorations were recorded in his travel journal and on his manuscript map, compiled during and shortly after his travels in the region.[1] His geographic details were derived from personal surveys, reconnaissance and from information shared by fellow traders, voyageurs and Native Americans he met during his twelve month mission of good will and discovery.

After his early September 1768 arrival in Boston, Carver offered its citizens an opportunity to subscribe to a publication of his journal and map. Because of insufficient local interest in his explorations and being desperate for money, he sailed for England in February 1769. His itinerary included collecting his overdue wages from the Crown and securing a publisher. Using a letter of introduction written by Reverend Samuel Cooper in Boston, Carver met face-to-face in London with Benjamin Franklin. As part of their meeting Carver likely enthusiastically shared his personal exploits, manuscript journal and map. After conferencing with Carver, Franklin wrote to Cooper thanking him “for giving me an Opportunity of being acquainted with so great a Traveller. I shall be glad if I can render him any Service here.”[2]

Carver finally self-published his journal-based book, Travels through the Interior Parts of North-America in the Years 1766, 1767 and 1768 in London in 1778. It was an immediate best seller, being reprinted by publishers in London and Dublin in 1779, again in London in 1781, and many further editions in the following decades; in 1780, a German translation was published in Hamburg.[3] A first edition copy was almost immediately acquired by Franklin, who in 1778, was America’s ambassador stationed in Paris, France.[4] Profits were not sufficient, however, to spare Carver from dying in poverty in early 1780.

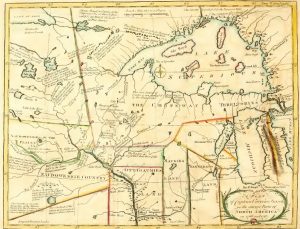

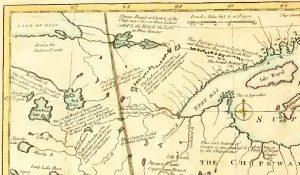

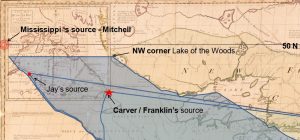

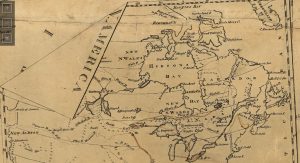

The book contained a small engraving of his manuscript map.[5] His published map, titled A PLAN of Captain Carver’s, was first engraved by Thomas Kitchin and subsequently less professionally re-engraved before being included in Travels. It shows White Bear Lake (470 N 950 W) as the main northern source of the Mississippi River. The source is correctly positioned relative to the continental drainage divides, Red Lake and Lake du Bois (hereinafter Lake of the Woods). Carver’s White Bear Lake might be any of the larger lakes (Itasca, Winnibigoshish, Turtle, Bemidji, etc.) in north central Minnesota. A note on the map reads “The Head Branches of the Mississippi are little known Indians seldom travel this way except War Parties.” The regional hydrology is shown with considerable accuracy.

Carver’s manuscript map coordinates were adjusted on his published map. For example, he placed the easternmost part of Lake of the Woods at 105 degrees West on his manuscript map whereas it is re-positioned at 96.6 degrees West on his published map (actual is approximately 940W). Almost all geographic and text details from Carver’s manuscript map were accurately transposed to his published map with little alteration or addition.

Dr. J. C. Lettsom, who likely sponsored the 1781 edition of Carver’s Travels, sent Benjamin Franklin a letter along with a copy of the new release.[6] Lettsom wrote,

“Sept. 13. 1781… May I request Dr. Franklin’s acceptance of the publications herewith sent. The octavo volume by Captn. Carver is more interesting, on acct. of the importance of a Country whose back settlements it describes, and which is one day destined, I hope to form the hemisphere of freedom”[7]

Carver investigated and collected considerable data on the source of the Mississippi River. This information appears on his maps and is expanded upon in Travels. His book relates,

“Not far from this Lake [Red Lake], a little to the south-west, is another called White Bear Lake, which is nearly about the size of the last mentioned. The waters that compose this Lake are the most northern of any that supply the Mississippi, and may be called with propriety its most remote source. It is fed by two or three small rivers or rather large brooks.”[8] “There are an infinite number of small lakes, on the westward parts of western head-branches of the Mississippi,”[9]

Steps Toward Peace

Britain’s resolve to continue war in America diminished by early 1782. British peace emissary Richard Oswald met the United States’ plenipotentiary Benjamin Franklin to determine grounds for securing an end to the war. Franklin, in Paris since 1776, responded with a list that included the voluntary surrender of Canada. American commissioner John Jay, previously on assignment in Madrid, emphasized their new country’s claim to lands extending west to the Mississippi River, from its northwestern source southward towards its mouth. By September 1782, beginning peace talks in Paris were replaced with productive negotiations.

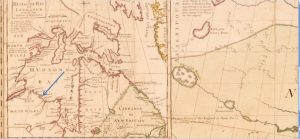

The first British-American draft accord, concluded in Paris, established among many requirements a boundary for the new United States.[10] Although no official map was part of any preliminary peace agreement, several editions of John Mitchell’s famous 1755 map of North America served as drawing boards from which the boundary of the United States slowly emerged.[11]

First Draft Peace Treaty (early October 1782)

Oswald and Jay successfully concluded the first draft peace agreement that in part defined the northwest portion of the divide between their two nations.[12] They agreed the boundary would run from the intersection of the 45th North parallel and St. Lawrence River “thence Streight to the South end of Lake Nipissing and then Streight to the Source of the River Missisippi.”[13] (This line later became known as the Nipissing Line.[14]) Both commissioners plotted their version of the line on separate Mitchell maps. They expected their respective governments to ratify the agreement.[15]

Because of illness, Franklin had limited involvement in finalizing the first draft treaty.[16] However, Lettsom’s gifted copy of Carver’s Travels, received in late September 1781, renewed Franklin’s opportunity to acquaint himself with Carver’s work. The explorer’s geographic and cartographic details provided Franklin with much needed, credible information about the extreme northwestern reaches of the Mississippi that now greatly interested the United States. Carver’s details on the river appear to have influenced how the draft boundary was plotted on both Jay’s and Oswald’s maps.

Once agreement was reached on the Nipissing Line, Oswald added his version of the line to his fourth edition Mitchell map.[17] Franklin must have shared his knowledge about the Mississippi headwaters with Oswald before the latter’s Nipissing Line was plotted.[18] The most northwestern portion of Oswald’s line roughly parallels Jay’s but it ends abruptly at the lower right edge of Mitchell’s inset map A NEW MAP of HUDSON’S BAY …. Oswald’s (Franklin’s) location for the source of the Mississippi closely approximates that shown on A Plan of Captain Carver’s.

The Nipissing Line on both maps lacked geographic distinctiveness; i.e., it wasn’t a natural boundary like a mountain ridge, river or lake, etc., and it angled tangentially across several degrees of latitude.

Negotiations Continue

Before the end of October 1782 peace negotiators in Paris were aware Britain had rejected the proposed boundary in the first draft treaty.[19] To negotiate, among other matters, a more acceptable northwestern boundary, the British Cabinet ordered Henry Strachey to Paris to assist Oswald.[20]

After discussions on the boundary were re-opened, Strachey likely soon sharpened the Americans’ focus on Dr. John Mitchell’s authoritative Mississippi map note.[21]

“The Heads of the Missisipi is not yet known; It is supposed to arise about the 50th degree of Latitude, and Western Bounds of this Map; beyond which Nth America extends nigh as far Westward as it does to the Eastward by all accounts.”[22]

The ensuing second brief, intense round of negotiations afforded the Americans an opportunity to revise their northwestern boundary. Both Jay and Franklin (the latter via Oswald) had earlier disclosed their desired course for the boundary on two different Mitchell maps thereby making known their best estimates for the Mississippi’s source. Newly arrived peace commissioner John Adams along with Jay and Franklin likely quietly and quickly responded to Strachey’s geographic directives and admonitions concerning the rejected northwestern boundary.[23] Adams recorded in his peace journal on November 2, “We have made two Propositions. One the Line of forty five degrees. The other a Line thro the Middles of the Lakes.”[24] Their simplest proposal was an extension of the existing New York – Canada 45th degree North latitude boundary starting at the St. Lawrence River and running westward to the Mississippi. The second “Middles of the Lakes” option was a line running, in part,

“. . . between that Lake [Huron] and Lake Superior, thence through Lake Superior Northward of the Isles Royal and Philipeaux to the Long Lake [actually a river inlet to Lake Superior], thence through the middle of said Long Lake and the water communication between it and the Lake of the Woods, to the said Lake of the Woods, thence through the said Lake to the most north- western point thereof, and from thence on a due western Course to the River Mississippi,”[25]

Most of the geography for the Americans’ new proposed boundary, from the intersection of the St. Lawrence and the 45th parallel through the Great Lakes to Lake of the Woods, was detailed in Carver’s Travels and on A Plan of Captain Carver’s. For example, Carver did a masterful job of describing and illustrating the passageway from Lake Superior to Lake of the Woods using information gleaned during his 1767 summer stay at Grand Portage.[26] The water communication route to Lake of the Woods, in Carver’s time, was known only to area natives, a few British fur traders and veteran French voyageur-traders.[27] In Carver’s words, he arrived

“at the Grand Portage, which lies on the north-west borders of Lake Superior. Here those who go on the north-west trade, to the Lakes De Pluye [Lac de la Pluie or Rainy Lake], Dubois [Lake du Bois or Lake of the Woods], &c. carry over their canoes and baggage about nine miles, till they come to a number of small lakes, the waters of some of which descend into Lake Superior, and others into the River Bourbon [Carver used this composite name to identify the southeastern arm of the river systems draining into Hudson Bay via Lake Winnipeg and the Nelson River].”[28]

“[Lake of the Woods] lies still higher up a branch of the River Bourbon, and nearly east from the south end of Lake Winnepeek [Winnipeg]. It is of great depth in some places. Its length from east to west about seventy miles, and its greatest breadth about forty miles.”[29]

“[Rainy Lake] appears to be divided by an Isthmus, near the middle into two parts: the west part is called Great Rainy Lake, and east, the Little Rainy Lake, as being the least division. It lies a few miles farther to the eastward, on the same branch of the Bourbon, than the last-mentioned lake [Lake of the Woods].”[30]

“Eastward from [Rainy Lake] lie several small ones, which extend in a string to the great carrying place [Grand Portage], and from thence into Lake Superior. Between these little lakes are several carrying places, which renders the trade to the north-west difficult to accomplish, and exceedingly tedious.”[31]

The northwest corner of A Plan of Captain Carver’s has additional information about the water – land route to Lake of the Woods. Carver replaced Mitchell’s erroneous estuary immediately west of Isle Royale with an accurate rendering of a small, short stream entering Lake Superior northeast of Grand Portage Bay.[32] Shown above “The Grand Portage” label are two small opposing arrows marking the Atlantic – Arctic drainage divide.[33] The map scale included near the top of his map permitted reasonable estimates for distances west of Lake Superior.[34] Coordinates for the south-eastern part of Lake of the Woods are very close to modern values.

In Paris, on November 30, 1782, the Preliminary Articles of Peace were endorsed by commissioners from both nations. For the northwestern boundary Britain chose the “Middles of the Lakes” option.[35] The details of boundary Article 2 appear to have been influenced by Strachey’s likely promotion of Mitchell’s faulty map details. The revised boundary awarded America an extensive tract of both real and “not-so-real” land in the northwest.[36] Article 2 states

” … thence along the middle of said Water Communication into Lake Huron, thence through the middle of said Lake to the Water Communication between that Lake and Lake Superior; thence through Lake Superior northward of the Isles Royal and Phelipeaux to the Long Lake; thence through the middle of said Long Lake and the water Communication between it and the Lake of the Woods, to the said Lake of the Woods; thence through the said Lake to the most Northwestern point thereof, and from thence on a due west Course to the river Missisippi.”[37]

The American commissioners’ mid-December 1782 homeward communication emphasized their northwestern boundary negotiating successes. The line “divides the Lake Superior, and gives us Access to its Western & Southern Waters.”[38]

Because the source of the Mississippi, according to Mitchell, was near the western edge of his map and about 500 N, Britain needed the latitude of the due west treaty line from Lake of the Woods to be less than fifty degrees.[39] Article 2 stated the divide line was to proceed due west from the most northwestern corner of Lake of the Woods to the Mississippi River (not its source).[40] Strachey was likely mindful of Mitchell’s latitude for the lake’s northwest corner, although not numerically quantified in the treaty, because he recognized his nation’s need to retain land abutting the Mississippi to preserve his country’s navigational rights to the river.[41]

About two months after signing the preliminary treaty, Franklin’s January 20, 1783 letter book entry revealed his knowledge about the “true” source of the Mississippi. He recorded

“The Limits of the thirteen United States, acknowledged by England, shall be formed . . . by a Line continued from Lake Superior through Long Lake, until the Lake of the Woods, by a Line tending towards the South and connecting the Lake with the River Missisippi.”[42]

Benjamin Vaughan, a close friend of Franklin’s and Britain’s intermediary between the Paris negotiators and Prime Minister Lord Shelburne and his cabinet in London, offered Shelburne some background information regarding Article 2. His letter to the first minister, dated February 21, 1783, advised

“The line to be drawn from the last boundary lakes [Lake of the Woods] to the Mississippi, probably should go South, and is by mistake said to go West. . . . It ought to stand in the definitive treaty perhaps to the nearest part of the Mississippi in a direct line; [or] from thence [Lake of the Woods], on a due South course to the Mississippi.”[43]

During the British parliamentarians’ debate focused on the preliminary treaty, Lord North, then Opposition Leader, sharply criticized the geography on which Article 2 was predicated. He orated

“The second article of the Provisional Treaty contained some very remarkable things; it states that a line drawn through the Lake of the Woods, through the said Lake, to the most N. W. point thereof; and from thence on a due west course to the River Mississippi.

“Now this being duly considered, would be found to be absolutely impossible; for this line would run far beyond the source of the Mississippi: thus [First Minister Shelburne] would agree as to the reciprocity; the mouth of this river is in the hands of the Spaniards; its source in the possession of the Americans; one side of it is within the boundaries ceded to the Colonies; the other is in the hand of the Spaniards; thus the river, the half of which is given to us by the treaty, belongs wholly to other powers, and not an inch of it, either at north or south, at west or east, belongs to us. This, no doubt, would establish the reciprocity beyond a cavil.”[44]

Terms of the November 1782 preliminary peace settlement were unknown in America when James Madison’s list of recommended reference books to be acquired and made available to Congress was read in Independence Hall in Philadelphia. Carver’s Travels was on Madison’s list.[45]

Official communication of peace with Britain reached Philadelphia on March 12, 1782.[46] Anne-Cesar, Chevalier de la Luzerne, the French diplomat stationed in Philadelphia since 1779, reflected to Charles Graver, Comte de Vergennes, senior French statesman in Paris, his thoughts on the new United States’ northwest boundary in a letter on March 19, 1783:

“. . . They [the United States] seem to have availed themselves chiefly of a journal printed by a Traveller, for in fixing the boundaries from Lake Superior to the sources of the Mississippi, one has no hope of obtaining a boundary so extensive in that area; One thinks that the Plenipotentiaries, by extending their possessions to the Lake of the Woods inclusively, are preparing for their posterity, in times still very distant, a communication with the Pacific Ocean.”[47]

The traveller mentioned by Luzerne could be none other than Captain Jonathan Carver. Carver’s geographic information and maps and their influence on America’s boundary-defining goals appears to have been known for some time in Philadelphia and beyond, and to have preceded the arrival of news of the peace settlement.

Within a few months after the signing of the 1782 Preliminary Articles of Peace, cartographers on both sides of the Atlantic were busy drafting maps of the new United States of America. William McMurray first offered his map to Philadelphians by subscription in early August 1783.[48] McMurray, a former Assistant Geographer to the United States, acknowledges using in toto the northwest quadrant of A Plan of Captain Carver’s to complete his map The United States According to the Definitive Treaty of Peace signed at Paris, Sept.r 3.d 1783.[49] In the lower right his inset map of North America exhibits an enticing open gateway to the West between Lake of the Woods and the source of the Mississippi.

John Cary’s plan, An Accurate Map of the United States of America,[50] was published in London in early August 1783. He borrowed numerous details from A Plan of Captain Carver’s. Cary labelled the traveller’s 1766 wintering locale on a westward tributary of the Mississippi and he illustrated Carver’s entire 1766-67 circle exploration route departing from and returning to Michilimackinac.

Conclusions

The Preliminary Articles of Peace were jointly signed by commissioners from the United States and Britain on November 30, 1782. Article 2 called for the extreme northwestern portion of the line of separation between their two nations to extend due west from the northwest corner of Lake of the Woods to the Mississippi River. The boundary defined in the preliminary treaty was confirmed verbatim in the Definitive Treaty of Peace signed in Paris on September 3, 1783.

Based on knowledge of Captain Jonathan Carver’s maps, surveys and travel narrative, the American commissioners knew the westward extension of the boundary from Lake of the Woods to the Mississippi was geographically impossible. Benjamin Franklin was most aware of the implications of Carver’s observations. By shrewdly acquiescing to Mitchell’s erroneous cartography, as promoted by the British, the Americans demonstrated their willingness to trade significant territorial interests along the Atlantic coast and “Nipissing country” for a vast additional tract of interior North America.

Various past and recent experts have postulated the Americans plotted the northwest boundary to Lake of the Woods because they considered it the source of a continuous water connection supplying the St. Lawrence River. The American negotiators’ knowledge of the continental drainage divide immediately west of John Mitchell’s Long Lake should dispel the mythology associated with the Lake Superior – Lake of the Woods water communication route. Shortly after signing the 1782 preliminary treaty, the American commissioners wrote,

“and having no Reason to think Lines more favourable could ever have been obtained, we finally agreed to those described in this Article: indeed they appear to leave us little to complain of, and not much to desire.”[51]

By 1807, the gambit on the due west line from Lake of the Woods to the Mississippi, although not free from controversy, compromise and re-definition, netted for United States of America all the territory visited and mapped by Carver, envisioned by Lettsom, and secured by Franklin, Adams and Jay in 1782.[52]

[1] Jonathan Parker, ed., The Journals of Jonathan Carver and Related Documents 1766-1770 (St. Paul, MN: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 1976), 25-44 (hereinafter Parker, The Journals). Parker did a comparative analysis of Carver’s published travel narrative and the versions of his MS journal and maps held by the British Library.

[2] National Historical Publications and Records Commission – Founders Online (hereinafter NHPRC-FO), http://founders.archives.gov/documents/Franklin/01-16-02-0056. Part of Franklin’s 27 April 1769 letter to Rev’d Samuel Cooper, a Congregational minister in Boston.

[3] Jonathan Carver, Travels through the Interior Parts of North-America in the Years 1766, 1767 and 1768 (London: Printed for the Author; and Sold by J. Walter, at Charing-cross, 1778 ), (hereinafter Travels). This edition of Carver’s book is available online at Internet Archive, https://ia601206.us.archive.org/22/items/travelsthroughin02carv/travelsthroughin02carv.pdf.

[4] NHPRC-FO, http://founders.archives.gov/documents/Franklin/01-28-02-0135. Travels is recorded on Franklin’s November 1778 list of loaned books.

[5] Parker, The Journals, 35. Carver’s 1766-67 manuscript map is part of the Collection of the British Library, catalogue number Add.8949.f.41.

[6] Ibid, 224.

[7] NHPRC-FO http://founders.archives.gov/documents/Franklin/01-35-02-0357. The letter is from Franklin’s acquaintance and Royal Society fellow in London. The copy of Travels sent to Franklin was a re-issue of Carver’s book sponsored by Lettsom in 1781 (see Parker, The Journals, 41-42). A 1781 edition of Travels was part of Franklin’s library; it is Volume 542 in Wolf and Hayes’ inventory of his books.

[8] Carver, Travels, 116.

[9] Ibid, 117. Carver’s interest in the northwesternmost branches of the Mississippi reflected his possible need to cross from the Mississippi to the Red River system en route to his intended 1767-68 wintering place near Fort La Reine on the Assiniboine River. The latter route was known to the local natives and was later used by fur traders.

[10] Mary A. Giunta, et al, ed., The Emerging nation, a documentary history of the foreign relations of the United States under the Articles of Confederation, 1780 -1789 (Washington, DC: National Historical Publications and Records Commission, 1996), 598-599 (reference hereinafter Giunta, Emerging Nation).

[11] A Map of the British and French Dominions in North America WITH THE Roads, Distances, limits, and Extent of the SETTLEMENTS, Humbly Inscribed to the Right Honourable The Earl of Halifax And the other Right Honourables, The Lords Commissioners for Trade & Plantations, By their Lordships Most Obliged and very humble servant Jno Mitchell, Published by the author Febry 13th 1755. The 3rd and 4th editions of the map were printed for Jefferys and Faden, Geographers to the King. The 4th edition, released circa 1775, omitted ‘and French‘ from the title.

For detailed information on the multiple editions of Mitchell’s 1755 map see the following by Matthew H. Edney: “John Mitchell’s Map of North America (1755); A Study of the Use and Publication of Official Maps in Eighteenth-Century Britain,” Imago Mundi 63 (2001): 63-85; “A Publishing History of John Mitchell’s Map of North America, 1755-1775,” Cartographic Perspectives 58 (Fall 2007): 4-27; “The Most Important Map in U.S. History,” Online publication at: Osher Map Center, Smith Center for Cartographic Education, University of Southern Maine, http://oshermaps.org/exhibitions/map-commentaries/most-important-map-us-history.

[12] Giunta, Emerging Nation, 597. The preliminary peace treaty was formally drafted in Paris on 5th-8th October 1782.

[13] Ibid, 598. The section of the Nipissing Line from the St. Lawrence River to Lake Nipissing was designated by King George III’s Royal Proclamation of 1763 as the southwest boundary of the new province of Quebec. The agreed upon line from the St. Lawrence R. to Lake Nipissing and straight to the source of the Mississippi R. was in accordance to Congress’s boundary objectives per Adams’ 1779 peace commissioner appointment and instructions. See NHPRC-FO http://founders.archives.gov/documents/Adams/01-04-02-0002-0001.

[14] Walter Nugent, Habits of Empire: A History of American Expansionism, (New York and Toronto: Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, Random House, 2008): 33-35. Andrew Stockley, Britain and France at the Birth of America, (Exeter, UK: University of Exeter Press, 2001), 64.

[15] Jay’s 3rd edition Mitchell map is held by the New-York Historical Society, Call No. NS4 M32.2.1A. Oswald’s 4th edition Mitchell map (also known as King George III’s Red-Lined Map) is held by the British Library, catalogue number K.Top (118.49.b).

[16] NHPRC-FO http://founders.archives.gov/documents/Franklin/01-38-02-0090. Franklin’s chronic problem with gout and kidney stones limited his participation in September – early October 1782 peace negotiations.

[17] Only faint red traces of Oswald’s Nipissing Line remain on his Mitchell map. His map eventually became part of George III’s extensive map collection. For further details on Oswald’s map see: J.P.D. Dunbabin, “Red Lines on Maps: The Impact of Cartographical Errors on the Border between the United States and British North America, 1782-1842,” Imago Mundi 50 (1998) and “Red Lines on Maps’ Revisited: The Role of Maps in Negotiating and Defending the 1842 Webster-Ashburton Treaty,” Imago Mundi 63 Part 1 (2011): 39-61.

[18] Because of illness, it is unlikely Franklin was present when Oswald plotted his Nipissing Line to the source of the Mississippi.

[19] Giunta, Emerging Nation, 623. News of Britain’s rejection of the first draft treaty was known to Oswald and Jay on 24 October 1782.

[20] Ibid, 631. British Under-Secretary of State for the Home Department, Henry Strachey, assisted Oswald to conclude the preliminary peace treaty. Adams and Franklin had previously met Strachey during a 1776 failed peace initiative on Staten Island.

[21] Ibid, 628. Shortly after his Paris arrival Strachey made known through Oswald he hoped the Americans would accept a line of longitude east of the Mississippi as their western boundary. The Americans (Jay) refused to consider this option and warned Oswald they would break off negotiations if it was insisted upon.

Ibid, 631. Strachey and commissioners from both nations spent considerable time studying earlier North American boundaries on a variety of maps as well as acts, laws and proclamations that might bear on establishing a revised boundary.

[22] Mitchell’s map note about the source of the Mississippi is located under the inset map A New Map of Hudson’s Bay at latitude 46.50 N. His text is similar to Henry Popple’s 1733 note on his gigantic map A map of the British Empire in America with the French and Spanish settlement adjacent thereto. Franklin was long acquainted with both of these early maps.

French cartographer Philippe Buache’s 1754 map Carte physique des terreins les plus eleves de la partie occidentale du Canada has remarks in French about the source of the Mississippi. Based on French army officers’ regional reconnaissance starting in the 1730s, the French concluded the source of the Mississippi lay south and nearby their trading route from Lake Superior to their forts on Rainy Lake, Lake of the Woods and Assiniboine River. Buache’s map can be viewed at McGill University’s digital map library http://digital.library.mcgill.ca/pugsley/IMAGES/3%20-%20300%20DPI%20JPGs/Pugs31.jpg.

[23] NHPRC-FO http://founders.archives.gov/documents/Adams/01-02-02-0001-0004-0009. As early as 1771 Adams was cognizant of Carver’s Mississippi basin explorations.

Relying on the correctness of Carver’s personal surveys and reconnaissance in the northern Mississippi region, Franklin, Adams and likely Jay may have immediately recognized the vast NW territory to be gained by accepting Strachey’s input. NHPRC-FO http://founders.archives.gov/documents/Franklin/01-38-02-0205. The American commissioners likely remained silent as Strachey possibly encouraged them to accept the correctness of Mitchell’s information about the Mississippi. Adams described Strachey as “artfull and insinuating a Man as they could send. He pushes and presses every Point as far as it can possibly go. He is the most eager, earnest, pointed Spirit.”

[24] Giunta, Emerging Nation, 631. An interval of only three days elapsed between the joint commissioners’ beginning review of Strachey’s maps and documents and the Americans’ presentation of their “Middles of the Lakes” proposal. NHPRC-FO http://founders.archives.gov/documents/Adams/01-03-02-0001-0004-0002. See Adams’ diary note for the Americans’ revised NW boundary line.

[25] Ibid, 650-652. The Americans’ “Middles of the Lakes” proposal was recorded on a separate folio and marked on the map Strachey carried back to London. Strachey’s map could have been Oswald’s 4th ed. Mitchell map (later known as King George III’s Red-Lined Map).

[26] Parker, The Journals, 180-191. Using information from Carver’s Travels and James Goddard’s journal Carver was at Grand Portage landing from 19 July to 8 August 1767.

[27] Veteran French voyageur-trader, Charles Boyer, traded for furs in the Rainy Lake / Lake of the Woods area in the 1740’s. He is likely ‘Mr. Boyce’ referenced in Major Robert Rogers’ letter dated 10 June 1767 (Parker, The Journals, 197). James Goddard’s journal reference to ‘Monsr. Boyiz’, was likely the same Charles Boyer (Parker, The Journals, 191). Boyer was in a partnership with Forrest Oakes in 1767, and later with his brother Michel Boyer, established a trading settlement at Rainy Lake. For the Rainy Lake 1771 Boyer settlement, see Glyndwr Williams, ed., Andrew Graham’s Observations on Hudson’s Bay 1767-1791, (Hudson’s Bay Record Society, London, 1969), 289. See also Merv Ahrens, Fort Lac la Pluie of the North West Company 177?-1821, (Fort Frances, ON: Fort Frances Times Ltd., 2006): 4, 5, 29.

[28] Carver, Travels, 106.

[29] Ibid, 113.

[30] Ibid, 114.

[31] Ibid, 115.

[32] The estuary / bay shown on Travel’s second map, A New Map of North America from the Latest Discoveries 1778, is likely Long Lake shown on Mitchell’s 1755 map. There is no such massive shoreline indent; its existence can be traced to Mitchell’s likely erroneous interpretation of regional features shown on earlier French maps (e.g. see Endnote 22 – Buache’s ‘Lac Long’).

[33] Carver, Travels, 106. Carver expanded on the meaning of the two opposing arrows on his map. He states

“[traders] carry over their canoes and baggage about nine miles, till they come to a number of small lakes, the waters of some of which descend into Lake Superior, and others into the River Bourbon.” This continental drainage divide is between North and South Lake on the Ontario – Minnesota international boundary.

Water features between Lake Superior and Lake of the Woods on Mitchell’s map promote Lake of the Woods as the source waters of the St. Lawrence drainage complex. The Americans’ faith in Carver’s hydrological details bolstered their conviction to their new NW boundary proposal. For details on the former drainage theory see William E. Lass, Minnesota’s Boundary with Canada It’s Evolution since 1783, (St. Paul, MN: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 1980): 15, 17 & 18. See also Dunbabin, Imago Mundi 50 (1998), 109 (Endnote 17).

[34] Using Carver’s map scale of “69.5 British Miles to a Degree” of longitude, America’s commissioners could approximate the distance from Lake Superior to Lake of the Woods and westward to “Mitchell’s Mississippi.”

[35] Prime Minister Lord Shelburne’s cabinet may have opted for the “Middles of the Lakes” boundary because it appeared “geographically distinct” and provided a “boundary of certainty.” The latter expressions were used in the British House of Commons when the New York – Canada boundary was debated before enacting the Quebec Act of 1774.

[36] If coordinates 500 N and 1060 W, implied by Mitchell’s Mississippi map note, were applied to a modern map, boundary Article 2 would have entitled America to territory extending north of the international boundary (490 N) and west to near Moose Jaw, SK, Canada. Thus the real and not-so-real territory gained by the American commissioners’ acceptance of Strachey’s/Mitchell’s faulty NW geography was the triangle-like territory extending from Carver’s source of the Mississippi to that of Mitchell’s and back to Lake Superior (Isle Royale and fictitious Isle Phelipeaux were also within the new proposed American territory).

[37] Avalon Project, http://avalon.law.yale.edu/18th_century/prel1782.asp#art2. Part of Article 2, Preliminary Articles of Peace, 30 November 1782 (font enhancements added by author).

[38] NHPRC-FO http://founders.archives.gov/documents/Adams/06-14-02-0076. American Peace Commissioners to Robert R. Livingston, Paris, 14 December 1782.

[39] Although the NW corner of Lake of the Woods is not shown on Carver’s published map, it’s likely about 510 N.

[40] The northwest corner of Lake of the Woods extends to 49.50 N on Mitchell’s map. British astronomer-surveyor David Thompson initially reported in 1797 an on-site measurement for the northwest corner of Lake of the Woods (outlet of the lake) to be 490 37′ N. Today’s geopolitical actual is at the NW end of Angle Inlet (Lake of the Woods) at 490 23′ 55″ N.

For the “deep water channel” adjusted NW point (490 23′ 04″.49 N) see Joint Report upon the Survey and Demarcation of the Boundary between the United States and Canada from the Northwesternmost Point of Lake of the Woods to Lake Superior, (Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1931), 109.

The Hudson’s Bay Co.’s (HBC) southern limit is boldly marked on Oswald’s map using a contrasting colour wash and a labelled bicoloured red and blue MS line coincident with the 49th degree North parallel. Its MS annotation reads “Boundary between the Lands granted to the Hudson’s Bay Company and the Province of Quebec.” The HBC MS line continues westward across the southern end of Lake of the Woods to the right edge of the inset A New Map of Hudson’s Bay. Shelburne had earlier in 1763 considered the company’s desired 490 N (southern) limit when he was First Lord of Trade but no document has been located that formally granted the HBC their long standing request.

[41] NHPRC-FO http://founders.archives.gov/documents/Franklin/01-38-02-0334. American Commissioners to R. Livingston, 14 December 1782, “Their possessing the Country on the River, North of the Line from the Lake of the Woods, affords a foundation for their claiming such Navigation; . . . The Map used in the Course of our Negotiations was Mitchells.”

[42] Giunta, Emerging Nation, 755-756. Digital images of Franklin’s letter copy book entry can be viewed online at National Archives – Fold3, http://www.fold3.com/image/#379298.

[43] Benjamin Vaughan Papers, American Philosophical Society, Mss.V46P, TLS Cy Vaughan to Lansdowne, William Petty, Marquis of, 21 February 1783.

[44] Full and Faithful Report of Debates in Both Houses of Parliament, Monday the 17th of February, and Friday the 21st of February, 1783 on the Articles of Peace, (Printed for S. Bladon, London, England, 1783), Numb. 13, 19 D2. Available online at Internet Archive, https://archive.org/details/cihm_36137. Lord North may have based his knowledge on William Faden’s maps of the British colonies in North America (1776 & 1783) that displayed much of Carver’s northern Mississippi R. details. Faden became King George III’s Royal Geographer in summer 1783.

[45] NHPRC-FO http://founders.archives.gov/documents/Madison/01-06-02-0031. During the second half of 1782 James Madison, Virginia’s delegate to the Second Continental Congress, identified Carver’s 3rd edition of Travels printed in London in 1781, as a recommended book to be acquired for Congress. His book list was reviewed by Congress on 24 January 1783.

[46] Giunta, Emerging Nation, 767. Luzerne, in his 9 February 1783 letter to Vergennes, indicated the peace terms with Britain were common news in America. NHPRC-FO http://founders.archives.gov/documents/Adams/06-14-02-0076, fn 2. Official notice from the American commissioners of the 30 November 1782 preliminary treaty, along with a copy of the latter, were received in Philadelphia on 12 March 1783.

[47]Giunta, Emerging Nation, 801-802; italics are as per Guinta.

[48] http://loc.gov/exhibits/mapping-a-new-nation/online-exhibition.html. McMurray’s map would have been America’s first map of the new nation had it not experienced publication difficulties. (Post-treaty details would not have been part of the map offered to the public by subscription as per McMurray’s receipt issued 13 August 1783.) See Harvard Map Collection, 2011 Toward a National Cartography: American Mapmaking 1782-1800, guest curator Michael Buehler, at: http://www.americanmapmaking.com/nation.php.

[49] Library of Congress map collection: http://www.loc.gov/item/gm71005423/.

[50]Library of Congress map collection: http://www.loc.gov/item/gm71005488/.

[51] NHPRC-FO http://founders.archives.gov/documents/Adams/06-14-02-0076. American Peace Commissioners’ letter to Robert Livingston, Paris, 14 December 1782.

[52] Negotiators from United States and Britain reached in March 1807 an agreement recognizing the 49th North parallel as the boundary between their territories from Lake of the Woods west to the Rocky Mountains. This agreement was formalized by the Convention of 1818. Boundary particulars of the section from Lake Superior west to Lake of the Woods were finalized by the 1842 Webster – Ashburton Treaty. The latter portion of the international divide line follows the land-water communication route investigated and described by Carver in 1767. Ancillary details on setting this portion of the U.S. – Canada boundary were summarized by U.S. Agent Major Joseph Delafield in Robert McElroy and Thomas Riggs, ed., The Unfortified Boundary, (New York, 1943): 403-465. See also William E. Lass, Minnesota’s Boundary with Canada, Endnote 33.

4 Comments

Fascinating article about a little known, and even less discussed, element in the Treaty. The maps are a wonderful addition to the narrative. I am delighted with the excellent end-notes.

Hugh, thanks for your observations and kudos. This important gap in the boundary record needs more of the experts’ attention.

Monsieur,

vous *êtes* l’expert!

Merci beaucoup.