Wars were fought by soldiers, but it is the campaigns and commanders that are remembered and studied. This is a shame because the soldiers had a remarkable range of fascinating experiences, often more exciting than those of the policymakers they served. And yet, the farther back in history one goes, the fewer personal stories of soldiers survive. The names of most British soldiers who served in America can be found on regimental muster rolls, but those administrative documents give only a few career details. Only a few personal narratives by British soldiers who served in the American Revolution are known to exist.[1] There is, however, a vast trove of records that contains some precious details about what many of these men experienced.

British soldiers could get pensions if they served well and survived their ordeals; in fact, it was just about the only profession that offered a pension during the 18th century. A board of examiners recorded the name, age, place of birth, trade and length of service of each pension applicant.[2] In addition to these demographic details, they recorded the infirmity that prevented the man from earning his own living, thereby making him a worthy candidate for government support. Reading through these lists, we find a broad array of maladies induced by military service: rheumatic, lost the use of his hand, dropsical, asthmatic, sore legs, lost his sight, fits, and a host of other ailments including the catchall “worn out.” Fewer than half of the men who served in America eventually applied for pensions (often long after the war due to lengthy military service),[3] but these pension board ledgers are often the only source of personal data that we have.

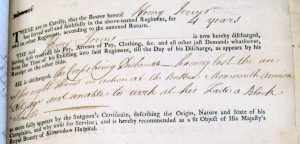

The discharge papers of some pensioners also survive.[4] A discharge is a document given to the soldier to prove that he had been legally released from his military obligation; most are printed forms with individual details handwritten into blank spaces. In addition to the personal data recorded in the admission ledgers, the discharges often include one or two sentences describing the soldier’s infirmities, sometimes including dates and locations where wounds or injuries were received. From these records we learn, for example, that John Hawkins of the 22nd Regiment, discharged in 1796 after serving for 24 years, was “Paralytic and was wounded in the neck 25th May 1778 at Bristol in New England, in the right thigh at Bedford, and lost the use of his right side in the West Indies,”[5] and that Isaac Miller, a 24-year veteran of the 35th Regiment, suffered from “a wound he received in the left Leg, at the attack of the American Intrenchments at Bunker Hill the 17th of June 1775, in consequence of which & the rheumatism he contracted in America from the Climate.”[6]

There are hundreds of similar statements among the discharges; the collection contains over 250 volumes, each containing documents for about 500 soldiers; I’ve read though the first 14 volumes so far, tedious but rewarding work with microfilm at the British National Archives. As fascinating and enlightening as these statements of battle wounds are, affording personal insight on many of the war’s great clashes, the discharges also reveal the many other hazards of military life. Among the hundreds of men who were simply “worn out” or contracted chronic illnesses are dozens of accidents and mishaps that speak to the variety of experiences that soldiers had.

From my notes on several hundred pensioners, below are a ten of the more interesting and revealing descriptions of disabilities incurred as a result of service in the American Revolution:

- John Hawkins, a writing clerk from Shankill near Lurgan in County Armagh, Ireland, joined the army in 1775 when he was 24 years old. He enlisted in the 37th Regiment of Foot. Although he was not discharged until 1788, his discharge reveals that he had been wounded during his second year of service; he was granted a pension because of “being wounded in the head in the action at Brandywine the 11 of September 1777 and Melancholy.” His melancholy did not stop him from serving another 10 years in a garrison battalion in Great Britain.[7]

- Samuel Newly (sometimes written Newby) had been with the 10th Regiment of Foot since 1758, and in North American since 1767, when war broke out in Boston in 1775. He spent 30 years in the army, taking his discharge in 1788 when he was 51 years old. He came through this long service without injury but, a musician by profession, he was “worn out on account of his long service and Constant Practice on Musical Wind Instruments.” He nonetheless reinlisted in the 54th Regiment and served another 5 years.[8]

- Robert Chapman enlisted with a recruiting party of the 54th Regiment of Foot in 1777 when his regiment was already at war in America. A 20 year old bricklayer from Fakenham, Norfolkshire, he spent the next 15 years in the army. When the war ended, the 54th Regiment was sent to Canada for several years. It was here that Chapman acquired “a lame Foot occasioned by being Frost bit in the Province of New Brunswick when on duty as an Escort to a Courier going to Canada.”[9]

- William McCreally, a blacksmith from Disset Martin in Londonderry, Ireland, joined the 3rd Regiment of Foot in 1773 when he was only 15 years old, a unusually young enlistment age. During his 15 years in the army he suffered not only from the enemy but from the forces of nature. After “having received a Ball in his leg, at the Eutaws in America” in September 1781, he went with his regiment to the West Indies. There he had “both his arms broke in a Hurricane in Jamaica.”[10]

- Charles Smith was a ten-year veteran in the 44th Regiment of Foot when he was “wounded at the Battle of Brandy Wine in his left arm” in September 1777. The weaver from Payton, Lancashire, who had enlisted in 1767 when he was 30 years old, continued to served until 1790. This was in spite an ordeal he survived when his regiment was sent to Canada part way through the war; he had “his right arm broken & the use of two fingers of his left hand destroyed when shipwrecked on his passage from New York to Quebec.”[11]

- John Hopwood was a butcher, a useful trade in an age when armies had to slaughter cattle in order to provide fresh meat for soldiers. A native of Hutton, Yorkshire, he’d enlisted in 1771 when he was 28 years old and served until 1792, spent his entire career in the 54th Regiment. His disabilities were partly due to the harsh life of a soldier and partly from practicing his trade, “being rheumatic and having lost the use of the two first fingers of his right hand, occasioned by an accident when killing cattle for the use of the army in 1778.”[12]

- Samuel Shepherd, from St. James, London, proved that the army’s butchers didn’t always have enough to work with. When he was discharged in 1788 after having served 15 years in the 31st Regiment of Foot, much of the time in Canada, the 36 year old had “an inveterate scurvey from living upon salt provisions for eleven years in America.”[13]

- Henry Brown served in three different regiments during his 20 years as a soldier. When he was discharged in 1790, the stocking maker from Dufftile, Derbyshire, was just 39 years old. Besides having been hurt “in America where he received a wound in the left knee” as a soldier in the 70th Regiment of Foot, he’d had an ignominious encounter with what was usually considered one of the soldier’s best friends; he was “bruised in the side & privates by a fall of a cask of rum on board the Charlestown frigate since which he cannot retain his water.”[14]

- Archibald MacEndow – a name that was spelled various ways – was born in 1754 in Ardnamarchan, Argyllshire, Scotland. When a new regiment, the 71st Regiment of Foot, was raised in Scotland for the war in America in 1775 he answered the call for recruits. MacEndow served for the entire war and took his discharge when it was over, but did not apply for a pension until 1792. The pension examining board recorded that he “was disabled at the siege of York Town in Virginia by the kick of a horse in the forehead and afterwards taken prisoner and when released he returned to his familiy in the highlands where he has lived since, subject to convulsion fits, which and real poverty, prevents his coming to solicit the pension sooner.”[15]

- John Wallace enlisted in the 76th Regiment of Foot as soon as the regiment was created in 1777, part of an expansion of the army in response to a widening war. The native of Kelso in Roxburghshire, Scotland, was 26 years old when he left his trade as a baker to become a soldier. On 6 July 1781 he was part of a rear guard of about 20 men that was attacked by a large American force at the Battle of Green Spring, Virginia; they fought desperately for some two hours, and Wallace was one of only a few who escaped unscathed. But at Yorktown the following month he was not so lucky; thunderstorms rolled through the area and he “lost his left eye by lightening on duty in America.” After the war “He went home to his friends in the Highlands of Sutherland, who in his absense had disposed of his little property, a house & garden. He then came to work at his Trade as a baker till his other eye in consequence of the suffering of the first was so dim he could not see sufficient to get his living.”[16]

[1] Only 11 lengthy narratives of British soldiers are known to exist. Two are available in standalone books: Don N. Hagist, A British Soldier’s Story: Roger Lamb’s Narrative of the American Revolution (Baraboo, WI: Ballindalloch Press, 2004), and Joseph Lee Boyle, From Redcoat to Rebel: the Thomas Sullivan Journal (Bowie, MD: Heritage Books, 1997). The remaining 9 are published in Don N. Hagist, British Soldiers, American War: Voices of the American Revolution (Yardley, PA: Westholme Publishing, 2012).

[2] Out Pension Admission Books, WO 116, British National Archives.

[3] Men who died in the service or deserted clearly did not apply for pensions. Discontinuities in service and other factors make it impossible to determine a precise number or portion of soldiers who served in America and later received pensions. Extensive study of the 22nd Regiment of Foot has shown that about half of the men who could eventually apply for pensions actually did so; the actual number may be higher.

[4] Soldiers’ discharges, WO 121, British National Archives. WO 97 and WO 119 also contain discharges. All of these pertain to men who were granted pensions; the discharges were apparently held by the pension office.

[5] Discharge of John Hawkins, WO 121/26/357.

[6] Discharge of Isaac Miller, WO 121/6/44.

[7] Discharges of John Hawkins, WO 121/1/6, WO 121/145/604.

[8] Discharges of Samuel Newly (Newby), WO 121/5/34, WO 121/142/357.

[9] Discharge of Robert Chapman, WO 121/14/442.

[10] Discharge of William McCreally, WO 121/5/117.

[11] Discharge of Charles Smith, WO 121/8/51.

[12] Discharge of John Hopwood, WO 121/14/459.

[13] Discharge of Samuel Shepherd, WO 121/5/152.

[14] Discharge of Henry Brown, WO 121/8/258.

[15] Discharge of Archibald MacEndow, WO 121/14/368.

[16] Discharge of John Wallace, WO 121/3/341.

5 Comments

A fascinating article that begs my question: is there any trick to deciphering the handwriting that one finds (untranscribed) in letters, pension records and other period documents? Some are very clear such as the DOI and US Constitution, but I have trouble reading letters to and from Washington that have no transcription. If I have trouble reading them could the original recipients have had the same reaction? Recently, I tried to reaad a pension record before looking at a transcription of the document. While I was able to decipher about 2/3 of the letter, I was unable to finish and some of my transcription was wrong. I wonder if it’s just my older eyes or have others confronted this challenge?

That’s a very good question, Steven.

I spend a lot of time reading manuscript material from the 1770s and 1780s, much of which is quite challenging to read (anyone who says “people had beautiful handwriting back then” hasn’t read much of it). There’s no single trick, but I can offer some pointers:

Acclimation is the biggest “trick.” The more handwriting you read, the better you become at figuring it out. This is partly because of recognizing the strokes, and partly because of acclimation to the sentence structure and word use. Often a word becomes recognizable because it sounds right in the sentence.

The more you read by a particular writer, the more you’ll be able to recognize her or his handwriting, both from the penmanship and the word choices.

Individual words can sometimes be recognized by comparing the strokes to other known words written by the same person, whether within the same document or in others.

I like to see the original documents in person whenever possible. But even with access to them, sometimes a photograph of the document is easier to read than the original. With the photo, you can zoom in, adjust the contrast, and do other things that might make the material more readable.

For documents written by famous people like Washington, there’s a reasonable chance that someone else has transcribed it already. Try an internet search on a readable sentence, and see if the whole document can be found already transcribed. But, check the transcription against the original to see if you trust it.

If the document is something that might contain standard language, like a will, pension deposition, military order or what have you, do internet searches on known phrases to find similar documents of the same genre.

Terminology can be a barrier, especially for specialized material like legal or military writings – it’s not easy to decipher handwriting when you don’t know the words or phrases that the person was writing. Look for documents dealing with the same subject matter that might contain similar words or phrases.

Decide whether an exact transcription is necessary for your purposes. If you can get the gist of a document, it may be sufficient to paraphrase it rather than transcribe it exactly, especially if the unreadable parts are peripheral to the theme.

Ask others for help! I work closely with Todd Braisted and a few other researchers, and we often exchange “what do you think this says” emails. It’s amazing how a person who has never seen the document before can often instantly recognize a word that someone else has puzzled over for hours.

There’s always some risk and judgment involved. It’s easy to transcribe something incorrectly because the word *didn’t* seem difficult to read – but factors from the original writer’s bad spelling to modern predispositions make a word or phrase seem different from what it is. Most researchers have a funny story or two. One of my favorites is a transcription of a British journal kept during the 1779 siege of Penobscot in which the writing frequently referred to “piquets”, a military term for outer sentries. The transcriber, unfamiliar with the terminology, rendered it as “Pequots” and assumed that the British had a corps of Indian allies working with them.

There’s an interesting range of handwriting types among letters of this era. The most legible letters are those from people important enough or rich enough who chose to hire a personal secretary or, somewhat counterintuitively, important people who were illiterate (often backwoods militia commanders or politicians). The penmanship on some of the first category of letters is beautiful. You can tell they’re using a secretary because every so often they had to write a letter on their own and the handwriting is usually ok, but not nearly as easy to read. The letters written by people in positions of authority who were nevertheless illiterate obviously had to be written by someone else, which was usually someone with good handwriting. An example of this latter category was Andrew Williamson, the South Carolina militia leader, who was illiterate. His letters are all easy to read, but it took the longest time for me to figure out that the letters were his because he would try to sign his name at the end of the letters someone else wrote and it was mostly a scribble that looking nothing like “Williamson.” The harder letters to read were by the educated class who had poor handwriting (John Rutledge of SC is a good example) and the barely literate who had to write their own letters. In the latter case, it’s all phonetic and you have to say the words out loud a couple times before you realize what he’s saying (examples include Moses Kirkland, a Loyalist militia leader from SC and George Galphin, the Patriots’ agent to the Creek Indians in Georgia). There are still some letters I took pictures of that I can’t decipher, but as Don said, it gets easier once you’ve fought your way through enough of the letters.

My favorite transcription error was an October 1780 letter from the Board of War in NC to General Henry William Harrington, also of NC. The writer was speculating about “the probability of the French landing six thousand men in Georgia.” The person doing the transcription saw this as “the French landing six Maryland men in Georgia.” Not that this happened, but 6,000 men vs. 6 Maryland men could have made a huge difference in the outcome….or perhaps no difference at all, depending on who you ask!

Another one I remember was the transcription from the original to the transcribed version of a document published in the Colonial and State Records of NC (generally a very dependable transcription, based on my comparison of certain letters with the original). In the transcribed version of the minutes of one June 1775 meeting of the Rowan County Committee of Safety, a man named Conrad Hildebrand was referred to as “Comrade Hildebrand.” I had to check the original to confirm it was an error. After all, ours wasn’t *that type* of “Revolution!”

Don, thank you for your article and again for reminding all of us that each soldier in the Revolutionary War, whether American or British, was first and foremost a living human being – each with a story of their own.

It seems sometimes when we deal with entire armies, divisions, or regiments, we forget that. Their disabled pension stories are swatches of their real lives.

Whether falling rum casts, scurvy, frost bite, wounds, or being kicked in the head by horses along with just plain being worn out… they paint real pictures of real people disabled by war. Great article!

Don, thank you so much for the terrific suggestions. One of them, zooming in, has been helpful. It’s too bad the Government can’t allocate more funding to transcribe handwritten items from the period, like a Federal Writers Program from the New Deal’s WPA. I can dream, can’t I?