The image of a rattlesnake was used as a symbol of the American colonies from the beginning of the French and Indian War to the end of the War for Independence. It appeared in printed caricatures, newspapers, and paper money, in addition to other media including flags, buttons and even on a cemetery monument. The basis of this pervasive imagery can be traced back to a May 9, 1751, tract by Benjamin Franklin.

Franklin wrote a satirical article entitled “Rattle-Snakes for Felons.” For years England had been shipping convicted criminals to her American colonies, which she justified as a way to help them grow in population. Franklin wrote that

“such a tender parental concern in our Mother Country for the welfare of her children calls aloud for the highest returns of gratitude … In some of the uninhabited parts of these provinces there are numbers of these venomous reptiles we call rattle-snakes: felons-convict from the beginning of the world. These, whenever we meet with them, we put to death, by virtue of an old law: Thou shalt bruise his head. But as this is a sanguinary law, and may seem too cruel; and as however mischievous those creatures are to us, they may possibly change their natures if they were to change the climate; I would humbly propose that this general sentence of death be changed for transportation.

In the spring of the year, when they first creep out of their holes, they are feeble, heavy, slow and easily taken; and if a small bounty were allowed per head, some thousands might be collected annually and transported to Britain. There I would propose to have them carefully distributed in St. James Park, in the Spring Gardens and other places of pleasure about London; in the gardens of all the nobility and gentry throughout the nation; but particularly in the gardens of the prime ministers, the lords of trade, and members of Parliament, for to them we are most particularly obliged.”

He closed his article by writing, “Rattlesnakes seem the most suitable returns for the human serpents sent us by our Mother Country.”[1]

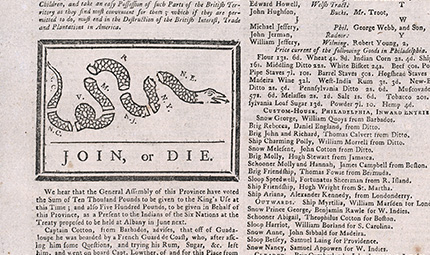

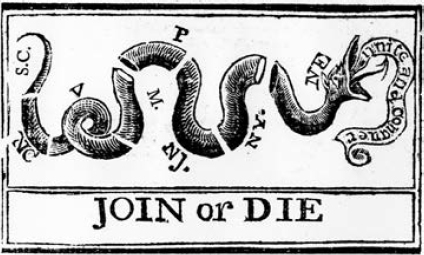

Three years later, the colonies’ western frontiers were under attack by the French and Indians. Representatives of the seven most northern colonies gathered in Albany on June 19. Their purpose was twofold: to secure a peace treaty with the Iroquois Nation and possibly garner their support in fighting the French and to form “under one government as far as might be necessary for defense.”[2] Franklin, one of the Pennsylvania delegates who had been appointed on April 8, presented a plan that would address the second purpose. It was unanimously approved, but when the delegates returned to their colonies, not one legislature would ratify it.[3] Franklin had to be thinking about his plan long before he left for Albany because an article dated May 9 appeared in the Pennsylvania Gazette calling for the colonies to unite against French aggression. The article was accompanied by an illustration depicting the colonies as a segmented snake and bearing the caption, “JOIN, or DIE.” At the time there was a common superstition that if the segments of a snake were put back together before sunset it would come back to life. This was probably one of the inspirations for the illustration.[4]

In addition to the Pennsylvania Gazette, four other newspapers included the snake image to encourage unity: the New-York Gazette and the New-York Mercury, both of May 13, the Boston Gazette of May 21, and the Boston News-Letter of May 23.

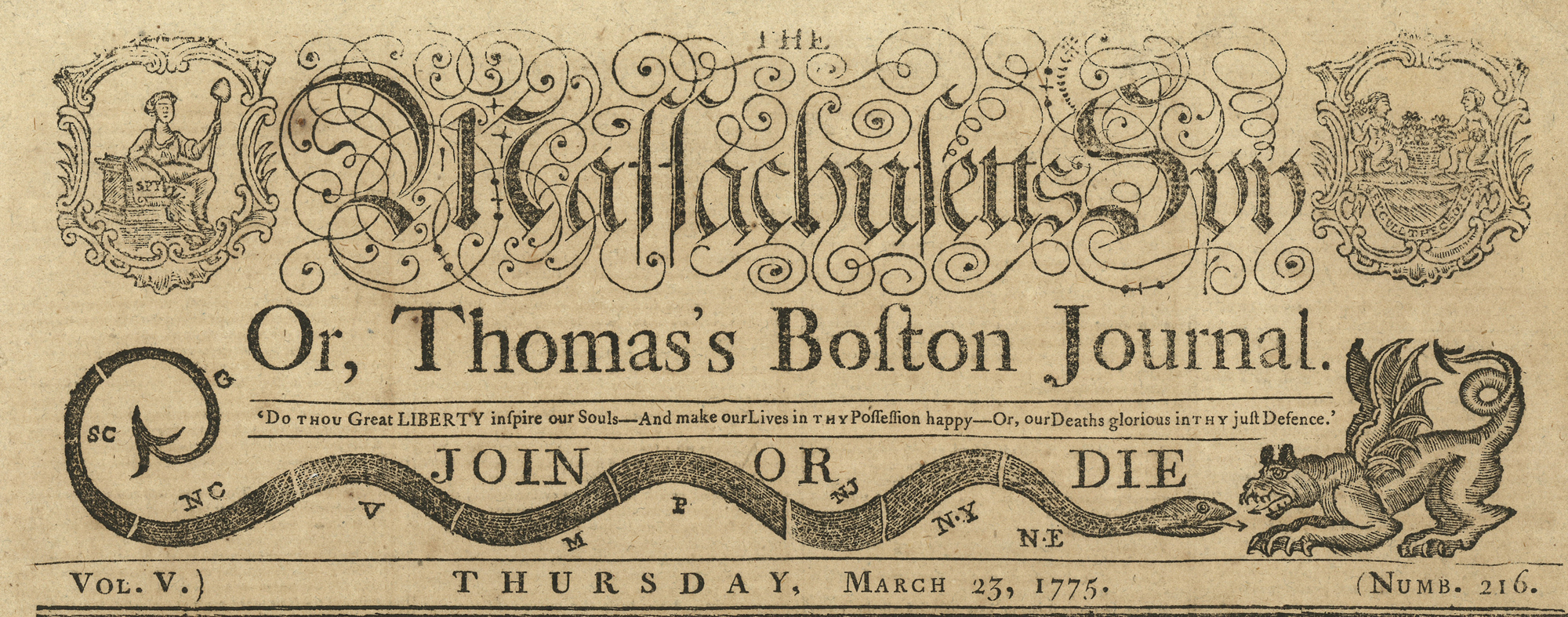

Twenty years later, on the eve of the Revolution, the snake image would again appear in print, but this time the enemy was not France but England. Isaiah Thomas in his Massachusetts Spy displayed the snake in his newspaper’s masthead confronting a dragon that symbolized England.

The masthead drew the reader’s attention to the line of text below the newspaper’s title: “Do THOU Great LIBERTY inspire our Souls – And make our Lives in THY Possession happy – Or, our Deaths glorious in THY just Defence.”

In addition to the Massachusetts Spy, two other newspapers included the snake image. They were the New-York Journal of June 23 (and December 15) and the Pennsylvania Journal of July 27.

In the December 27, 1775 edition of The Pennsylvania Journal, Benjamin Franklin wrote about why he believed the rattlesnake was the ideal image for the colonies:

“[The rattle-snake’s] eye excelled in brightness, that of any other animal, and that she has no eye-lids. She may therefore be esteemed an emblem of vigilance. She never begins an attack, nor, when once engaged, ever surrenders: She is therefore an emblem of magnanimity and true courage. As if anxious to prevent all pretensions of quarrelling with her, the weapons with which nature has furnished her, she conceals in the roof of her mouth, so that, to those who are unacquainted with her, she appears to be a most defenseless animal; and even when those weapons are shewn and extended for her defence, they appear weak and contemptible; but their wounds however small, are decisive and fatal. Conscious of this, she never wounds till she has generously given notice, even to her enemy, and cautioned him against the danger of treading on her.

Was I wrong, Sir, in thinking this a strong picture of the temper and conduct of America? The poison of her teeth is the necessary means of digesting her food, and at the same time is certain destruction to her enemies. This may be understood to intimate that those things which are destructive to our enemies, may be to us not only harmless, but absolutely necessary to our existence …

‘Tis curious and amazing to observe how distinct and independent of each other the rattles of this animal are, and yet how firmly they are united together, so as never to be separated but by breaking them to pieces. One of those rattles singly, is incapable of producing sound, but the ringing of thirteen together, is sufficient to alarm the boldest man living.”[5]

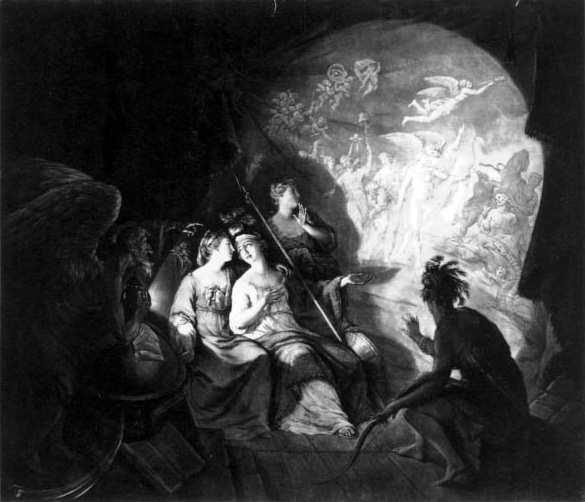

The rattlesnake appeared in other iconography, particularly in political cartoons and related prints. In a print called The Oracle by John Dixon published in April 1774, the winged Father Time is joined by the countries of Britannia, Hibernia, Scotland, and America. They gaze upon a ghostly projection depicting a hopeful view of Great Britain at a time when not only America , but Scotland, and Ireland were threatening to revolt. Cornucopias representing prosperity are overflowing, Fame is marching forward as the serpents of discord cower, and Britannia is hoisting the liberty cap high, symbolizing her claim as the most liberal nation on earth. It is important to note however that the seated figure of Britannia and the crouching figure of America are armed.[6]

By 1778, Tea Tax Tempest had been revised by a German artist to convey the opposite meaning in a print titled The Oracle; in 1783 a British artist pubished a new version with a narrative balloon. The winged Father Time descrbes the scene projected by a magic lantern, saying, “There you see the Little Hot Spit Fire Tea pot that has done all The Mischief – There you see the Old British Lion basking before the American Bob Fire whilst the French Cock is blowing up a form About his ears to Destroy him and his young Welpes – There you see Miss America Grasping at the Cap of Liberty – There you see the British Forces be yok’d and be cramp’d flying before the Congress Men – There you see the thirteen Stripes and Rattlesnake exalted – There you see the Stamp’d paper help to Make the Pot Boil – There you see etc, etc, etc.” The rattlesnake appears twice, on the thirteen-striped flag carried by the American soldiers and in the smoke veering toward the British soldiers.[7]

In the 1779 print Ô qu’el d’Estain, a cock, a lion, and a rattlesnake attack a leopard; the phrase “Tu la voulu” can be translated as “You wanted it.” In the four corners are the heads of a cock labeled “La France,” a lion labeled “L’Espagne,” a rattlesnake labeled “L’Amerique,” and a leopard labeled “L’Angleterre.” The quote below is from Voltaire: “Du sein de la tyrannie naquit l’independance” (“From Tyranny’s Breast Independence if Born”).[8]

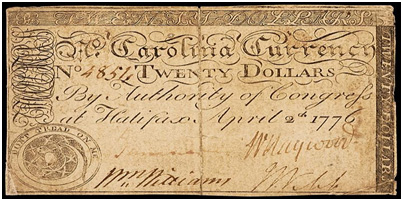

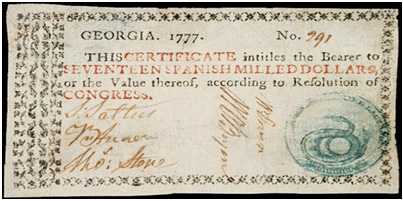

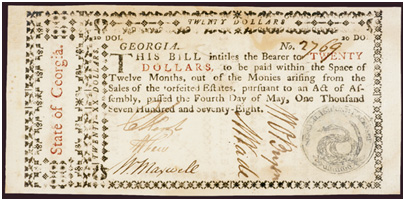

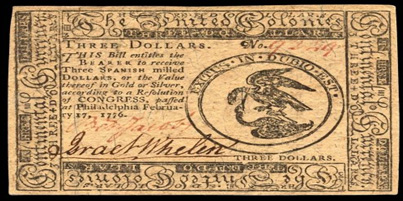

Another printed form sometimes bearing the rattlesnake image was the printed money issued in the colonies.

In 1782, when Britain was coming to grips with defeat and negotiating a treaty of peace, English cartoonists portrayed the United States as a vengeful and menacing rattlesnake. These political cartoons, called satires or caricatures, were not printed in newspapers but rather published by printmakers and sold individually.

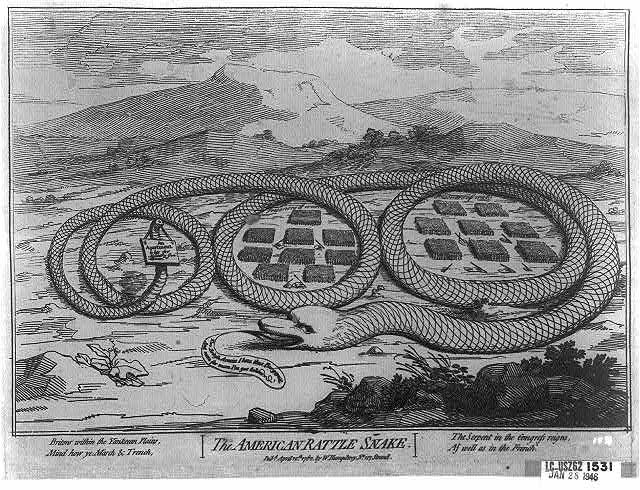

In an April 1782 print called The American Rattle Snake, a giant serpent encircles two armies and boasts: “Two British Armies I have thus Burgoyn’d, And room for more I’ve got behind.” A sign is posted over the vacant third coil reads, “An Apartment to Lett for Military Gentlemen.”[9]

Paradice Lost, published a month later, shows four British cabinet officials, Lord Bute, Lord North, Lord Sanwich, and Lord Shelburne or Germain, being driven out of the “Garden of Eden” by prominent Whig politician Charles Fox as the American rattlesnake looks on defiantly.[10]

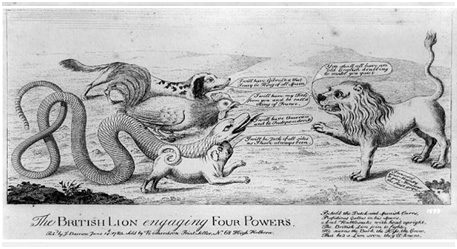

In June, The British Lion Engaging the Four Powers depicted a lion representing England confronting four opponents: a pug dog representing Holland, a rattlesnake representing America, a fighting cock representing France and a spaniel representing Spain. The pug says, “I will be a jack of all sides as I have always been.” The rattlesnake says, “I will have America and be independent.” The Fighting cock says, “I will have my title from you and be call’d King of France.” The spaniel says, “I will have Gibraltar, that I may be King of all Spain.” The lion says, “You shall all have an Old English drubbing to make you quick.”[11]

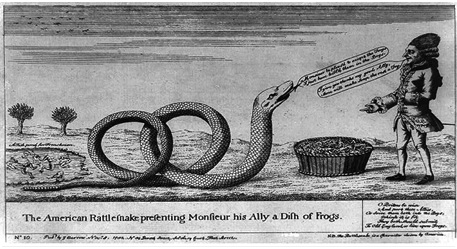

November 1782 saw publication of The American Rattlesnake presenting Monsieur his Ally a Dish of Frogs. Unlike the other prints, this was a pro-British image that included a verse advising Britons to drive a wedge between the Americans and the French during the peace negotiations.[12]

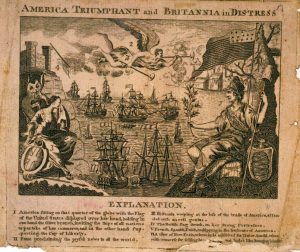

America Triumphant and Britannia in Distress first appeared in the Weatherwise’s Town and Country Almanac for 1782; the author is unknown. On the right hand side, America is sitting on the globe that includes the continent of North America. Displayed over her head is the Flag of the United States. She holds in her right hand an olive branch, inviting the ships of all nations to partake of her commerce; in her left hand she holds a pole bearing the Cap of Liberty. Her shield bears the image of the rattlesnake. Britannia is seen weeping on the left hand side.[13]

[1] Walter Isaacson, A Benjamin Franklin Reader (New York: Simon and Schuster, 2003), 150-51.

[2] “Letter to the PRINTER of the LONDON CHRONICLE July, 1754,” in Albert Henry Smyth, ed., The Writings of Benjamin Franklin, Vol. II, (Brooklyn, NY: Haskell House, 1970).

[3] Leonard W. Labaree, et al. eds., The Papers of Benjamin Franklin, Vol. V (New Haven, CT: 1959- ), 160; Benjamin Franklin, The Autobiography of Benjamin Franklin (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1964), 210.

[4] Lawrence Monroe Klauber, Rattlesnakes: their Habits, Life Histories, and Influence on Mankind

(Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1956), 350.

[5] Isaacson, A Benjamin Franklin Reader, 264-66.

[6] Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, British Cartoon Prints Collection.

[7] Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, British Cartoon Prints Collection.

[8] Joan D. Dolmetsch, Rebellion and Reconciliation: Satirical Prints on the Revolution at Williamsburg (Williamsburg, VA: The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, 1976), 170-171.

[9] Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, British Cartoon Prints Collection.

[10] Dolmetsch, Rebellion and Reconciliation, 180-181.

[11] Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, French Political Cartoon Collection.

[12] Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, British Cartoon Prints Collection.

[13] Dolmetsch, Rebellion and Reconciliation, 193-194.

Recent Articles

When Some Americans First Lost Their Constitution

The Great Contradiction: The Tragic Side of the American Founding

Reluctant Ally: The Dutch Republic and the American Revolution

Recent Comments

"The Complicated History of..."

Carole, Thank you, I appreciate that. I agree that much of what...

"The Sieges of Fort..."

I very much enjoyed your well-written article. Interest in the site continues,...

"An Enemy at the..."

Bob: Great Article! I never heard of Abraham Carlile and his fate....