Earlier this year the AMC network aired a new series, Turn, about the Continental Army’s Culper Spy Ring, based on Alexander Rose’s book, Washington’s Spies. In one episode, the character of Benedict Arnold refers derisively to General Horatio Gates as “Granny Gates.” One might think it was a bit of literary license on behalf of the screenwriter, yet the nickname is found in dozens of books, many written by well-known scholars: Joseph Ellis, John Ferling, Thomas Fleming, Christopher Hibbert, and Richard Ketchum, among others – each saying that men in the 1770’s called him “Granny Gates.”

And all of them are, apparently, wrong.

Horatio Gates was a career officer in the British army before he moved to Virginia in 1774. He was eligible for a half-pay pension and, since he was still in British territory, could have simply retired at age forty-seven as a country farmer. When the Revolution began a year later, he went to Mount Vernon, met George Washington, and traveled to Philadelphia where the Continental Congress appointed both of them as generals. Gates became the first adjutant general and was given command of the Northern Department. As such, he was the ranking officer when British general John Burgoyne surrendered after the Battle of Saratoga. Three years later he was in command at the American defeat at Camden. He was still respected enough to serve in the New York state legislature later in life, and was buried at Trinity churchyard in New York City with other war veterans. Yet historians now disparage him – based on an obscure novel, along with the memories of two soldiers who were interviewed seventy years after the Revolution ended.

The Boston:1775 blog caught this in an article on September 21, 2013, showing that the first appearance of the phrase “Granny Gates” comes from Seventy Six, a novel by John Neal, published in 1823.[1] The next reference comes from a letter written in 1855 by 95 year old veteran Nathan Knowlton, and referred to obliquely in a book from 1897;[2] the third from an interview with Samuel Downing, a 102 year old veteran, published in 1864.[3] In Downing’s case, he said that Gates was an “old, granny looking fellow,” and did not use the full phrase. This constitutes the entire testimony of people who say Horatio Gates was referred to by the name “Granny.”

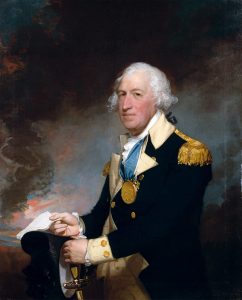

The legend itself is only half the story. The references from Knowlton and Downing were forgotten for decades, and may have stayed buried but for two descriptions in Samuel W. Patterson’s Horatio Gates: Defender of American Liberties, from 1941. Even he did not use the phrase “Granny Gates,” but he described Gates with words that echo to this day. He did so by reviewing a painting from 1782, now at Independence National Historical Park: “As Charles Willson Peale portrayed him, he had a youthful appearance, though his hair was graying and rather thin above his long, well-modeled face. His shoulders were a bit stooped…his cheeks were ruddy and full.” In itself the description is fair, since Patterson clearly shows he is referring to the Peale painting. Three hundred ten pages later Patterson described Gates again – eight years after the portrait, and thirteen years after his victory at Saratoga: “Gates was sixty three years old, though he looked older. His hair, pure white and very thin above his forehead, hung rather low down the back of his neck. His shoulders stooped to a noticeable degree.”[4]

Consider the next description, by Christopher Ward, in his widely respected book, The War of the Revolution, published in 1952: “Gates was of medium height, his body not muscular, his shoulders somewhat stooped. He seemed older than fifty, his age at that time.” Notice that Ward took the two separate descriptions above and combined them, so Gates no longer had a youthful appearance at fifty but looked older than he was – which is how Patterson described the general later in life. The reference to being stooped no longer hinges on the painting, as it did with Patterson.[5]

The turning point came in 1961, with publication of Daniel Morgan: Revolutionary Rifleman, by Don Higginbotham. He combined Patterson, Ward and Downing into a portrayal of the general who (until then) was basically unscathed: “Gates did not look like a soldier; he was small of stature, ruddy-faced, and bespectacled, with thin graying hair. His enemies, who were numerous, said he looked like a ‘granny.’”[6] Higginbotham’s work is rich in footnotes, yet this has no citation to its dubious origins.

Now consider George Athan Billias, in George Washington’s Generals, published three years later: “He seemed much older than his fifty years. He was stooped in stature, ruddy-cheeked, had thinning gray hair, and wore spectacles perched precariously on the end of his long nose.”[7]

Higginbotham mentioned the image of eyeglasses, which is backed up by witnesses of the time. A Hessian soldier who saw Gates at Saratoga in 1777 wrote home about both his gray hair and glasses, which he “always wears.”[8] James Wilkinson, Gates’s adjutant, also mentioned the general’s glasses in his memoirs.[9] Billias, however, created the image of glasses being perched on the end of his nose – something those who followed him seem to have taken as gospel.

Now Christopher Hibbert, in Redcoats and Rebels: The American Revolution through British Eyes, from 1990: “He looked considerably older. Grey-haired and round-shouldered, with

spectacles constantly slipping down his long nose, he seemed more like an elderly schoolmaster than an officer.”[10]

Now John Ferling, in John Adams: A Life, from 1992: “Gates, gray and overweight, with spectacles habitually perched on his nose (his men later called him ‘Granny Gates’) hardly looked like a soldier.”[11] At least Ferling allows that the epithet was not used at the time of Saratoga, but readers may not have caught the distinction.

Now Richard Ketchum, in Saratoga: Turning Point in America’s Revolutionary War, from 1997: “Fifty years old, he looked much older, because of a pronounced stoop, wispy gray hair,

thick spectacles worn at the edge of his nose…all of which prompted one soldier to describe him as an ‘old, granny looking fellow,’ whereupon he acquired the nickname ‘Granny Gates.’”[12]

Now Carl Green, in The Revolutionary War, from 2002: “Gates was given the nickname ‘Granny’ because his gray hair, ruddy face, and spectacles that often slid down his nose made the fifty year old soldier look like an old woman.”

Now Joseph Ellis, in His Excellency: George Washington, from 2004: “Horatio Gates was called ‘Granny Gates’ because of his advanced age (he was fifty) and the wire-framed spectacles dangling from his nose.”[13]

Now Bruce Chadwick, in The First American Army: The Untold Story of George Washington and the Men behind America’s First Fight for Freedom, from 2007: “An overweight, ruddy faced former British officer who wore thick glasses, he was called ‘Granny Gates’ by some of his men.”[14]

Now Alex Storozynski, in The Peasant Prince: Thaddeus Kosciuszko and the Age of Revolution, from 2009: “Gates, hunched over, with thinning gray hair, chubby ruddy cheeks, and

spectacles perched at the tip of his nose, looked older than his fifty years and was called ‘Granny Gates’ by his men.” [15]

The whole thing resembles the childhood game in which a teacher whispers a benign phrase to one student, who whispers it to another, and so on, until the end result is garbled. Neal and Knowlton used the phrase Granny Gates; Downing added “granny looking,” Patterson added stooped, ruddy-faced and gray hair, Ward moved the idea of Gates “looking older” from age sixty three to fifty, Billias added the bit about the glasses at the end of his nose, and so on. Instead of a fifty year old man with youthful appearance, as Patterson wrote, we have a gray haired, stooped old man peering through his glasses and being called Granny. Patterson literally described a painting, but now we have this caricature – a grandmother, a weakling – slapped onto a career military officer, and based on the memories of two men speaking seven decades after the events occurred.

Ketchum is noteworthy. He used the original “granny looking fellow” from Downing’s 1864 interview (without a citation) but then wrote, “whereupon he acquired the nickname ‘Granny Gates.’” In this phrasing, Ketchum implied that Downing said it during the war and others picked it up soon after. In Founding Conservatives, published in 2013, David Lefer wrote, “He was known throughout the army as ‘Granny Gates.’” Now, according to Lefer, everyone in the army used the phrase – which is a neat trick, since there is no evidence that anyone ever said it.[16]

The image is so widespread it may be impossible to erase. A search of Google Books lists forty different works published since Patterson’s that use the name Granny when talking

about Gates; even renowned authors like Benson Bobrick, Richard Brookhiser, Thomas Fleming, Robert Leckie and John Pancake appear on the list, all apparently inspired by Higginbotham, or Billias, or Ferling, or Ketchum – and all without citation. Leckie made the Granny Gates claim in a book on American life after the War of 1812.[17]

Thus for 191 years, since Neal’s novel first appeared, our man Gates has had a cloud over his stooped and gray head, gathering strength with each generation. It is so colorful, so cute. Continental soldiers muttered the words “Granny Gates” when their commander walked by. Who could resist repeating it? Yet it is baffling that respected authors who spent years researching the Revolution have all accepted the claim without question. They all seem to operate under the idea that if so-and-so said it, the story must be true – which allows specious claims, like this one, to become accepted as fact in our literature.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT: I am grateful to Eric Schnitzer of Saratoga National Historical Park for his contribution to this article.

[1] John Neal, Seventy Six, or Love and Battle (Portland, Maine, 1823), 71. Google Books uses the 1840 version.

[2] Massachusetts Society of the Sons of the American Revolution, Historical Memoranda: with

Lists of Members and their Revolutionary Ancestors (Boston: by the Society, 1897), 329.

[3] E. B. Hillard, The Last Men of the Revolution (Hartford: N. A. and R. A. Moore, 1864), 15.

[4] Samuel White Patterson, Horatio Gates: Defender of American Liberties (New York: Columbia University Press, 1941), 50, 369.

[5] Christopher Ward, The War of the Revolution, in two volumes (New York: Macmillan, 1952), 1:500.

[6] Don Higginbotham, Daniel Morgan: Revolutionary Rifleman (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1961), 62.

[7] George Athan Billias, George Washington’s Generals (New York: William Morrow, 1964),

[8] Ray W. Pettingill, ed., Letters from America, 1776 – 1779: Being Letters of Brunswick, Hessian and Waldeck Officers with the British Army During the Revolution (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1924), 113.

[9] James Wilkinson, Memoirs of My Own Times (Philadelphia: Abraham Small, 1811), 1:302.

[10] Christopher Hibbert, Rebels and Redcoats: The American Revolution through British Eyes (New York: W. W. Norton, 1990), 69.

[11] John Ferling, John Adams: A Life (Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1992), 128.

[12] Richard Ketchum, Saratoga: Turning Point in America’s Revolutionary War (New York:

Henry Holt, 1997), 52.

[13] Joseph Ellis, His Excellency George Washington (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2004), 81.

[14] Bruce Chadwick, The First American Army: The Untold Story of George Washington and the

Men Behind America’s First Fight for Freedom (Naperville, Illinois: Sourcebooks, 2007), 186.

[15] Alex Storozynski, The Peasant Prince: Thaddeus Kosciuszko and the Age of Revolution (New York: Thomas Dunne/St. Martin’s, 2009), 34.

[16] David Lefer, The Founding Conservatives: How a Group of Unsung Heroes Saved the American Revolution (New York: Sentinel / Penguin, 2013), 162.

[17] Benson Bobrick, Fight for Freedom: The American Revolutionary War (New York: Atheneum Books for Young Readers, 2004), 74; Richard Brookhiser, George Washington on Leadership (New York: Basic Books, 2008), 25; John Ferling, John Adams: A Life (Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1992), 128, and Almost a Miracle: The American Victory in the War of Independence (New York: Oxford University Press, 2007), 232; Thomas Fleming, Liberty: the American Revolution (New York: Viking, 1997), 245; Robert Leckie, George Washington’s War (New York: Harper Collins, 1992), 381, and From Sea to Shining Sea: From the War of 1812 to the Mexican War, the Saga of America’s Expansion (New York: Harper Collins, 1993), 244 – 45; John S. Pancake, 1777: The Year of the Hangman (Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1977), 149 – 50.

13 Comments

I am not a fan of Horatio Gates but I adore solid biographical research. I have followed this process of slow, cumulative distortion in many historical figures. Great sleuthing!

Thank you for another look at Gates. He is an enigma to me and other South Carolinians. Thank goodness he ordered Francis Marion out of the Camden camp when he did!

The process of research is finding and distilling and this article is a fine example of that. What’s disturbing to me is how the sobriquet may have tainted my own perceptions of Gates. Three examples suffice: Gates’ interaction with Benedict Arnold at Saratoga, his involvement in the ‘Conway Cabal’ and his flight after the Battle of Camden. While ‘Granny Gates’ may have been applied (fictionally) as a term of endearment by those who served under Gates, it also connotes an unpleasant stereotype that’s wholly unnecessary to make the reader dislike Gates’ character, which I continue to do.

Congratulations on this refreshing review!

I would like to see “granny” put into a wider context. I have not looked at Neal’s book, but what it the term meant in some military usage during the Revolution and the next decades was midwife, and there were clever plays on birthing in military puns, as when the Rochester Daily Advertiser in 1836 (as reprinted in the Albany Argus of 23 August 1836) quoted an article in which C. A. Wickliffe of Kentucky referred to William Henry Harrison “as an expeditious granny, having delivered Gen. Proctor of the British Army of six hundred children in forty minutes.” The Advertiser labeled this as “a new version of an old story, of which General Gates, of Saratoga memory was hero”—which by the way is an earlier example of this usage than 1855. There’s another example in the Portland ME Daily Advertiser of 19 July 1862: “All eyes were turned to “granny Gates” after the surrender of Burgoyne.”

The term was widely applied to Harrison in 1840. The Vermont Phoenix of Brattleboro on 7 February 1840 quoted a defense of WHH: “‘They call him,’ said Mr C., ‘an “Old Granny”—very well—he is a granny, who will deliver this country on the 4th of March, 1841, of the greatest litter of political scamps that were ever produced.’” The 16 April 1840 Boston Courier piece by “Old Seventy-Six” entitled “Granny Harrison” says this: “I occasionally find in the Tory papers the nickname, ‘Granny,’ applied to the present Whig candidate for the Presidency. I know not if it be a dictionary word, and if it be, I know not the meaning of it as now used. But I have a distinct recollection of its meaning in the days of the Revolution. It was synonymous with midwife.” Old Seventy-Six continued: “Previous to the storming of Stony Point, the British had given this name to General Wayne—I know not why. I recollect, however, it was currently reported at the time, that on entering the fortress, and meeting the British officers, he [unidentified] exclaimed lustily—‘Here comes Granny Wayne!’ As Harrison was a pupil of this veteran, and served under him afterwards in subduing the Indians, perhaps the name was bequeathed to him by his tutor.’”

Old Seventy-Six continued with an anecdote which he thinks he saw in print somewhere: “It is said that Gates and Burgoyne had been school-fellows in early life. After the surrender of the latter at Saratoga, while dining together, Burgoyne said to Gates, ‘I little thought, when we were at school together, that you would be a warrior. I thought you might make a pretty clever man-midwife.’ ‘Well,’ replied Gates, ‘you find I am a man-midwife to your sorrow; for I have delivered you of upwards of seven thousand men.” The “Revolutionary meaning” of “the term GRANNY” was undoubtedly “midwife,” according to Old Seventy-Six.

It’s fascinating that what may have begun as a compliment shaded quickly into a slur as people forgot the original contexts.

There are definite references to Continental soldiers calling Gen. Joseph Spencer “Granny Spencer,” and that was clearly not meant as a compliment.

I posted without seeing that J. L. Bell in his BOSTON 1775 printed a piece on Granny Gates by Jack Kelly that anticipates some of what I quoted.

I also see that interesting results appear if you search Google with three words–Burgoyne Gates Granny.

Congratulations on dispelling a long standing myth. This is another example of why it is critical to rely on primary rather than secondary sources for historical research. General Gate’s star was tarnished after Camden, but no reason to disparage him as “Granny”. Further his hesitancy for a general engagement was shared (for good reason) by many other Continental Army Generals including Washington.

His looks nor any elderly personality traits were impactful on his command decisions, so there is no reason for historians to perpetuate the myth that you found unsubstantiated. Great work!

This is a nicely argued piece. Thanks for the effort. I’m also pleased to see that Eric Schnitzer continues to help out the rest of us so effectively.

TURN is not a miniseries; the second series has begun production & the show will reappear on AMC later this year. It has its pleasures, including some excellent performances. However, although the show claims to be based on history, there are numerous inaccuracies.

So, look at TURN as a continuing opportunity to explain “the real story” or “the full story” of things Revolutionary. I thoroughly enjoyed your article & hope to see more.

This is tantalizing!

It looks to me as if the story started early with the military-maternal pun on “delivery.” The New-York Packet 23 Dec. 1788, gave the anecdote about Burgoyne and Gates which was copied at least a couple of dozen times in the next couple of decades. Granny apparently comes in around 1840.

ANECDOTE

Soon after the renowned capture of Burgoyne, he was in company with his aged vanquisher and a number of inferior officers, who in consequence of a few bottles, found their spirits in a jocose te[m]perature, war[sic] ceated [sic], and the prisoner in a measure forgot his captivity. In the height of conversation, Burgoyne reproached Gates for undertaking so hazardous a charge in such a declined period of life–told him he was fitter for a midwife than a General–A Midwife! (exclaimed the old veteran) to your experience, I for sometime past acted in capacity of a General, yet have not deviated far from the office of Midwife, as I safely delivered you of 7000 men.

This anecdote was in Father Abraham’s Almanac for 1798 and was reprinted for years.

The gossip theory? From aged midwife to “granny”?

I have noticed that I’ve sometimes, when skimming, confused Gates and Gage… And for what it’s worth, there is definite contemporary evidence that Gage was referred to as an “Old Woman”*. That’s not calling Gage a granny, but just to throw it out there… I wonder if there’s any chance the GATES story got amplified by the Gage contemporary references, due to the similarities of the names…

* John Andrews to William Barrell, Mar 18, 1775 [the Postscript of Monday Morning, the 20th], in Proc. of MHS (1866) 8:401.

I don’t know what’s more impressive: Your fine, disciplined scholarship—or that so many historians are either sloppy, don’t use attribution, they just make things up, or they editorialize with the choice of their words.

One often-published historian in a 2013 book that I didn’t have the stomach to finish, filled it with phrases like: “Washington growled to a British friend” and “John Adams barked.”

C’mon, people. Let our subjects’ words or paintings speak for themselves. Granny Gates, indeed.

General Henry Dearborn was nicknamed “Granny” by his men during The War of 1812. He also served under Benedict Arnold during The Revolution. I wonder if that somehow influenced Neal’s novel. Fascinating to see all of these writers ape each other!