Billy Flora was cold.

That was not surprising. He was crouched in the lee of a pile of shingles next to a burnt out building in the early hours of December 9, 1775, with a musket in his hands and a rime of ice forming in the marshes of the Great Dismal Swamp that lay on both sides of the narrow spit of land on which he and the other forward sentries were stationed. About seventy yards in front of him, at the other end of the “Great Bridge” was a force of red-coated British soldiers in their palisade fort, named Fort Murray after the Royal Governor of Virginia, John Murray, Lord Dunmore.

About a quarter mile behind him, built across the northern end of the island on which the town of Great Bridge was located, stood the Patriot breastwork;[1] a seven-foot high palisade wall fronted with a six-foot wide parapet of earth.[2] Behind that breastwork was stationed the 60 men of the Patriot main guard commanded by Lieutenant Edward Travis.[3] And about a quarter mile behind them, camped near the local church was the main Patriot force of about 650 men of the 2nd Virginia Regiment and the 1st (Southern) Minute under the command of Colonel William Woodford.[4]

Cold and tired, Billy’s thoughts drifted. He recalled his early childhood. Born in Norfolk, Virginia about 1755 to Mary Flora, a “free Negro,”[5] his early years were little different from those of most of the other children his age. Like most of his contemporaries he had little formal schooling. At the age of eight he was apprenticed to Joshua Gammon, a carter and wagon master.[6] On completion of his apprenticeship in 1770 he had gone to work – first for John Fenstress, then, in 1773, for William Brissie.[7]

Shortly after his eighteenth birthday, in compliance with the Virginia Militia Law[8] that required all able bodied men between the ages of eighteen and sixty to be enrolled in their local militia company, he enlisted in the Princess Anne County Militia and met regularly for drill with the other men of his neighborhood.[9] Never rich, but not dirt poor either, Billy lived a life little different from most other people.

That is, until the trouble came.

Although there had been some dissatisfaction and unrest as a result of measures taken by Parliament in the wake of the French and Indian War, passions erupted when Governor Dunmore had sailors from HMS Magdalen remove the Colony’s store of gunpowder from the magazine in Williamsburg.[10]

Fearing for the safety of himself and his family, on June 8 Governor Dunmore had fled Williamsburg, taking refuge on board the 24 gun frigate HMS Fowey[11] in the York River. For the next two months he employed the sailors and marines of the naval assets in the Chesapeake to conduct sporadic raids on the plantations along the rivers, principally to get supplies. Then, following the arrival of three companies of regulars of the 14th Regiment from St. Augustine in late July,[12] he raised the King’s Standard, calling all loyal citizens to join him, and began raiding aggressively throughout the countryside, seeking out and destroying Patriot military assets.

Many residents of Norfolk and the surrounding communities flocked to sign an oath of allegiance to the King. But not Billy. He joined the Princess Anne District Minute Battalion. When Dunmore occupied Norfolk, Billy slipped out of Norfolk and made his way to the patriot forces.[13]

On November 14, following his rout of a muster of the Princess Anne District Minute Battalion at Kemp’s Landing, Dunmore ordered a palisade fort to be constructed at the north end of the Great Bridge over the southern branch of the Elizabeth River[14]. Although derisively called the “Hog Pen” by the patriots,[15] it was garrisoned by 30 to 50 Regulars and volunteers and mounted two 4 pounder cannons.[16] It effectively interdicted the causeway through the Great Dismal Swamp that was the only practical approach to Norfolk by land.

The Patriot response had been to send a force of about 215 riflemen and light troops under the command of Lieutenant Colonel Charles Scott to confront Dunmore’s forces at the Great Bridge and keep them from raiding into the countryside.[17] They had arrived on November 28 and immediately began skirmishing, with Scott’s riflemen taking “pot shots” at the garrison of Fort Murray on an almost continual basis, to which the defenders replied with musket and cannon fire.[18]

Billy made his way to Great Bridge with other volunteers of the Southern Minute Battalion. He was probably set to work constructing the palisade breastwork fronted by an earthen parapet that now lay across the north end of the island on which the town of Great Bridge was situated, or on the flanking breastwork and artillery emplacement built on a small island to the west in anticipation of the arrival of Colonel Robert Howe of North Carolina with a strong train of artillery well supplied with ammunition.[19]

As he shivered in the early morning cold, Billy looked forward to the arrival of those cannon. They would quickly knock that flimsy British fort to splinters, opening the way for the Patriots to drive the British out of Norfolk.

Faintly he heard the drums in the Patriot camp a half mile distant beating reveille. His duty as sentry was almost over and he was more than ready to get back to camp for a meal and some rest.

What was that?

He had heard something else. He peered over the top of his shingle pile. There, barely visible in the first weak light of the coming dawn, he saw men replacing the planks that the British had removed from the floor of the Great Bridge. It took only an instant for Billy to realize that the Redcoats were about to mount an attack.

He raised his musket and fired.

Almost simultaneously the other sentries also fired, then fired again. After two or three shots, the other sentries ran back up the causeway to give warning to the fore guard at the Patriot breastwork.

Not Billy.

Realizing that the firing of the sentries well might be ignored because of the constant sniping that had been going on for days, Billy resolved to delay the British for as long as he could. From behind his pile of shingles, he loaded and fired again. And again. And again. Finally, after being fired on by an entire platoon[20] of British, he broke cover and ran for the protection of the Patriot breastwork.

The element of surprise having been lost, the British began firing chain shot and grape shot from the two 4 pounders in Fort Murray at the Patriot breastwork. With shot from the British guns flying all around him, Billy scrambled over the plank that gave access to the breastwork. But before dropping down to safety, he paused to take up the plank and pulled it within the breastwork so as to deny it to the approaching enemy.[21]

Billy quickly reloaded, possibly with buckshot rather than single ball.[22] It seemed only seconds later that Lieutenant Travis ordered “Make Ready!” Then “Take Aim!” As the British van crossed a small bridge some fifty yards in front, Travis ordered “Fire!”[23]

A thunderous volley rang out and a number of the Grenadiers of the British van went down, including their commander, Captain Charles Fordyce. Fordyce immediately sprang to his feet, waved his hat and, shouting “The day is our own!” rallied his men.

Another volley rang out. More British soldiers went down, including Fordyce. This time he did not rise, having been struck by 11 balls.[24]

The British, recognizing that musket fire would be ineffective against the fortified Patriots and that pausing to fire would only expose them longer to the fire of their enemies, valiantly attempted to carry the breastwork at the point of the bayonet. But as fast as they could advance up the narrow causeway they were cut down by repeated Patriot volleys.

Within minutes, 66 of the 120 men of the 14th Foot who had embarked on the assault were dead or wounded.[25] The rest streamed back to Fort Murray, hurried along by fire from the riflemen posted on the small island to the left of the breastwork.

As the firing died away, Colonel Woodford arrived with the main body of the Patriot force. But it was all over. From first volley to last, the Battle of Great Bridge had lasted less than five minutes.[26] Although some urged him to pursue the defeated British, Woodford prudently refrained, realizing that if he were to lead his force down that narrow causeway up which the British had just advanced and retreated, the British would be able to do to him what his forces had just done to them.[27]

In the days that followed the Patriot forces drove Dunmore and the British out of Norfolk and subsequently out of Virginia.

Billy and the other men who had fought at Great Bridge that morning probably never realized it, but they had just won a critical victory which, though tiny, indeed almost insignificant as battles go, was of immense importance to the Patriot cause. For, as a consequence of the Patriot victory at Great Bridge, Lord Dunmore and the British were driven from Virginia, and for the next five years, Virginia was essentially free of any organized British presence.[28] During those five years Virginia, one of the wealthiest and most populous of the nascent United States, sent thousands of men[29] and tons of arms, munitions and supplies[30] to Washington’s Army — Men, arms, munitions and supplies that were critical to keeping that army in existence[31] so that, six years later, in 1781, it could march south with our French allies to defeat the British Army under Lord Cornwallis in the action that insured our independence. It was one of the earliest, smallest, shortest battles of the entire American Revolution,[32] yet one of the most important ones. (This significant battle will be depicted in a diorama at the American Revolution Museum at Yorktown, opening in late 2016.)

After the taking of Norfolk, Billy probably went home for awhile. But he did not stay.

In November of 1776, as the war heated up, he enlisted in Captain William Grymes’s company of the 15th Virginia Regiment of the Continental Line.[33] Muster rolls and pay rolls show that Billy served in the Virginia Line for the rest of the war, moving from the 15th Virginia to the 11th Virginia and then to the 5th Virginia as the Virginia Line shrank and regiments were consolidated.[34] Billy missed being captured with the bulk of the Virginia Line when the army under General Benjamin Lincoln surrendered at Charlestown in 1780. He was among the troops that besieged and captured Lord Charles Cornwallis and his army at Yorktown in 1781.[35]

With the cessation of hostilities, Billy returned to civilian life. He either began or continued to operate a successful cartage and livery stable business based in Portsmouth. Sometime after 1782 he was wealthy enough to purchase freedom for his wife and two children. In 1784 he purchased two lots in Portsmouth and is believed to be the first African-American to own land in that town. For a number of years thereafter he bought and sold several houses and unimproved lots. By 1810 he was paying taxes on three large wagons, three two-wheeled carriages and six horses.[36]

In 1806 he entered a claim for the land grant due to veterans of the Continental Army. The surviving affidavits supporting his claim testify to his being highly regarded as a soldier who, contrary to popular modern perceptions, served throughout the war side by side with white Virginia soldiers.[37]

But Billy was not through with military service. In 1807, at age 52, when the militia of Norfolk and Portsmouth were called to service as a result of the attack on the Frigate Chesapeake, “Billy appeared, armed and accoutered, declaring that he would ‘be buttered’ (the only oath he swore) if he could not use old Betsy again.” In 1812 he served another short stint as a home guard during the Battle of Craney Island.[38] In 1818 he received a land grant of 100 acres in the Virginia Military District, which he probably sold to one of the land companies attempting to settle the area.[39]

Billy Flora died ca. 1820 at Portsmouth ”at a good old age,” respected and honored by the people of Norfolk, Gosport and Portsmouth as one of the true heroes of the American Revolution.[40]

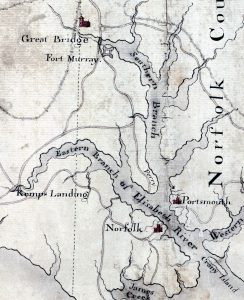

[FEATURED IMAGE AT TOP: Source: Benson J. Lossing, Pictorial Field Book of the Revolution, Volume II (1850)]

[1] The layout and dimensions of the battlefield at Great Bridge were determined from three contemporary maps:

Samuel Leslie, “A View of the Great Bridge near Norfolk in Virginia when the action [occurred] between a Detachment of the 14th Rgt. And a body of the Rebels” by Captain Samuel Leslie of the 14th Foot, a participant in the action” (Clements Library, University of Michigan) (hereafter cited as Leslie, “A View of the Great Bridge …”). This map shows the important elements of the field — Fort Murray, the Rebel fortifications, the town of Great Bridge, the causeway and the church where the main body of the Patriots were encamped, but is un dimensioned and out of proportion (Leslie did not advance past Fort Murray at any time before or after the battle.)

James Stratton, “Plan of the Post at Great Bridge, on the South Branch of the Elizabeth River, Established the 5th of February 1781” by James Stratton, Corps of Engineers. Published by him, October, 1788.” (Library of Congress) (hereafter cited as Stratton, “Plan of the Post at Great Bridge …”) Stratton was attached to the Queen’s Rangers under John Graves Simcoe during Cornwallis’s advance into Virginia. His map is properly proportioned but lacks a scale or dimensions.

“Survey Report for repairs to be made to the south causeway between the Great Bridge and the old rampart where the causeway ends.” Dated July 18, 1787, pursuant to the order of the Norfolk County Court of June 21, 1787 for repairs to be made to the south causeway between the Great Bridge and “the old rampart where the causeway ends.” (Archives, City of Norfolk). This map includes the dimensions of the causeway and the distances between key points from the south end of the Great Bridge and the site of “the old rampart”

By combining the information from these three maps it was possible to estimate key distances: from Fort Murray to the Patriot fortification (approximately 390 yards {~1/4 mile}) and from the Patriot fortification to the Church where Woodford’s main body was encamped (approximately 400 yards {~1/4 mile}).

[2] “[We] were ordered by the Governor to [attack] a strong Body of the rebels [who were] as securely intrenched against any Numbers as Nature or Art could place them. … We knew their Situation well, & knew that it was impenetrable, … their Breastwork & Stockade seven feet high, with loop Holes to fire through, …” Letter from “JD” [Captain John Dalrymple, 14th Regiment] To The Earl Of Dumfries, Virginia, January 14, 1776, (National Archives, UK. PRO CO 5/40 folio 124) (hereafter cited as “JD” to the Earl of Dumfries). “Figure to yourself a strong breastwork built across a causeway, on which six men only could advance abreast.” Extract of a letter from a Midshipman on board His Majesty’s Ship Otter, Commanded by Captain Squire, dated January 9, 1776. In Peter Force, American Archives, S4: V4: 0540. See also Leslie, “A View of the Great Bridge …” Because of the need to secure the defenders from fire of two 4-pounder artillery pieces in Fort Murray, the Patriot “stockade” was probably fronted with an earthen parapet 8 or more feet thick faced with logs or fascines.

[3] John Burk, The History of Virginia, from the First Settlement to the Present Day, (Petersburg, Dickson Pescud, 1805) 442 (Hereafter cited as Burk, The History of Virginia). “… lieutenant Travis commanded … at the breastwork. … The troops at this place, besides the ordinary guard of twenty-five men [muskets], consisted of forty of Mead’s company [muskets], to these he added forty of the Augusta Riflemen [Rifles].” The 65 musket armed men would have been stationed at the breastwork, with a few stationed in the ruins of the houses near the bridge as advanced sentries. The 40 riflemen would have been stationed at its supporting earthwork to the left.

[4] Charles H. Lesser (ed.) The Sinews of Independence; Monthly Strength Reports of the Continental Army. (Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 1976) 13 (hereafter cited as Lesser, The Sinews of Independence). The Virginia troops present at Great Bridge on December 9, 1775 consisted of the 2nd Virginia Regiment (273 present, fit for duty), the Culpeper Minute Battalion (137 present, fit for duty), and the Southern (Princess Anne District) Minute Battalion (197 present, fit for duty). In addition there were about 150 volunteer militiamen from North Carolina. Hugh F. Rankin, The North Carolina Continentals, (Chapel Hill, University of North Carolina Press, 1971), 24. Total ~757 men. Subtracting the 105 men with Travis at the breastwork leaves ~652 men with Woodford at the main camp.

[5] Paul Heinegg, Free African Americans of Virginia, North Carolina, Maryland and Delaware. (By the author, 2010.) Entry for the Flora Family. <http://www.freeafricanamaericans.com>. (Hereafter cited as Heinegg, Free African Americans of Virginia)

[6] Order Book for the Norfolk County Court of Pleas and Quarter Sessions, 1763-65, Pg. 15.

[7] Elizabeth B. Wingo, Norfolk County, Virginia Tithables, 1766-1780, (Norfolk, E. B. Wingo, 1985.) 128.

[8] The last Militia Law tobe officially adopted in Virginia was “An Act for the better regulating and disciplining the Militia,” enacted in April, 1757. Frederick S. Aldridge, Organization and Administration of the militia system of Colonial Virginia, (Ph. D diss., American University, 1964) 158. Subsequently the law was simply renewed on an annual basis until 1775. This law provided that “… the lieutenant … of the militia, in every county … shall list all male persons above the age of eighteen years, and under the age of sixty years … under the command of such captain as he shall think fit …” William Walter Hening (ed.), The Statutes at Large, Being a Collection of all of the Laws of Virginia…, (Richmond, for the Editor, 1820) 8: 93.

[9] Although Section 4 of the Virginia Militia Law excepted “… free mulattoes, negroes, and Indians …” from the obligation to “… be armed …” and Section 7 directed that they appear at musters without arms, those provisions of the law were clearly ignored, at least in Billy Flora’s case, as he appeared at Great Bridge and during the War of 1812 fully armed and accoutered.

[10] Virginia Gazette (Purdie), April 21, 1775; Virginia Gazette (Dixon & Hunter) April 22, 1775; Log, HMS Magdalen April 20, 1775; Dunmore to Dartmouth, May 1, 1775. Cited in, John E Selby, The Revolution in Virginia, 1775-1783. (Charlottesville, University of Virginia Press, 1988) 1.

[11] Mark Mayo Boatner III, Encyclopedia of the American Revolution, (New York, McKay, 1976) 1148; Virginia Gazette (Holt) Aug. 12, 1775.

[12] “By order of the Committee for this Borough, I am directed to inform the Convention of the arrival of troops this day … from St. Augustine, … sixty in number, … another vessel with more troops [is] hourly expected.” Committee of Norfolk to Peyton Randolph, President of the Virginia Convention, Norfolk, July 31, 1775. William Bell Clark (ed.) Naval Documents of the American Revolution, (Washington, U.S. Navy Department, 1964) I;947 (hereafter cited as Clark, Naval Documents). “On Monday last [July 31] arrived here from St. Augustine, about sixty soldiers … These with about forty more, which are hourly expected, are to compose a body guard for his Excellency the Governor, …” [Holt’s Virginia Gazette, Wednesday, August 2, 1775]. See also Purdie’s Virginia Gazette, Friday August 4, 1775; James Parker to Charles Stewart, [Norfolk] 4 August [1775] in Clark, Naval Documents, I;1064.

[13] The Virginia troops present at Great Bridge on December 9, 1775 consisted of men of the 2nd Virginia Regiment the Culpeper Minute Battalion, the Southern (Princess Anne District) Minute Battalion and about 150 volunteer militiamen from North Carolina. [See endnote 4.] Flora was most likely a member of the Southern (Princess Anne District) Minute Battalion as the Southern Minute Battalion was the only force present at the Battle of Great Bridge that was raised in the counties (Isle of Wight, Princess Anne) around Flora’s home in Norfolk. E. M. Sanchez-Saaverda, A Guide to Virginia Military Organizations in the American Revolution, 1774-1787, (Westminster, MD, Heritage, 1978) 16-38. (hereafter cited as Sanchez-Saaverda, Guide).

[14] “I determined to take possession of the pass at the Great Bridge, which secures us the greatest part of two counties to supply us with provisions. I accordingly ordered a stockade fort to be erected there, which was done in a few days; and I put an officer and twenty-five men to garrison it, with some volunteers and negroes.” Dunmore to Howe, November 30, 1775 in Force, American Archives, S4: V3: 1713.

[15] “Our army has been for some time arrested in its march to Norfolk by a redoubt, or stockade, or hog pen, as they call it here, by way of derision, at the north end of this bridge.” Thomas Ludwell Lee to Richard Henry Lee, Williamsburg, Decr. 9, 1775 in Clark Naval Documents, 4:26.

[16] “Two four-pounders were sent to them yesterday …” Leslie to Gage, December 1, 1775 in Force, American Archives, S4: V4: 0349.

[17] Burk, The History of Virginia, 439.

[18] [The Rebels] have continued firing small-arms at it in an irregular way … without any other consequence than that of slightly wounding two or three of our men. .” Leslie to Gage, December 1, 1775 in Force, American Archives, S4: V4: 0349. “We still keep up a pretty heavy fire between us, from light to light.” Letter from Lieutenant Colonel Scott to a friend in Williamsburg, dated Great Bridge, December 4, 1775 in Force, American Archives, S4: V4: 0171.

[19] Letter from Colonel Scott to a Friend in Williamsburg, December 4, 1775, in Force, American Archives, S4: V4: 0171. “The Carolina forces are joining us. One company came in yesterday, and we expect eight or nine hundred of them to-morrow, or next day at farthest, with several pieces of artillery, and plenty of ammunition and other warlike stores.” See also Skelton Jones and Louis Hue Girardin, The History of Virginia, from the First Settlement to the. Present Day (Continuation), (Petersburg, Dickson Pescud, 1816). 4, 78. “At the same time, batteries were commenced for the cannon hourly expected…” and J. H. Norton, Jr. to J. H. Norton Sr., Williamsburg, Decr 9 1775, PRO, Colonial Office, 5/40, 282-83 in Clark Naval Documents, 4:25. “Colo [Robert] Howe from Carolina with about 600 Men & a good Train of Artillery are daily expected to join Woodford, when a general Engagement will probably happen.”

[20] “The conduct of our centinals I cannot pass over in silence. Before they quitted their stations they fired at least three rounds as the enemy were crossing the bridge, and one of them, who was posted behind some shingles, kept his ground till he had fired eight times; and after receiving [the fire of] a whole platoon, made his escape over the causeway into our breastwork.” Virginia Gazette (Pinkney, December 20, 1775) 3.

[21] Although apparently common knowledge to the people of Norfolk at the time, documentation of Billy Flora as the courageous “centinel” reported in the Virginia Gazette appears to be traceable to the verbal testimony of Captain Thomas Nash.

Nash was an 18 year old private at the time of the Battle. He was the only American wounded (in the hand) during the engagement. He served in the Virginia Line during the Revolution. After the War, he went on to become a wealthy planter, Justice of the Peace and respected leader of the Norfolk community. He served as a Captain of Militia in the War of 1812. . H. Clarkson Meredith, Some Old Families and Others, (Norfolk, Tidewater Typography, 1976?)) 268-272; Colonel William H. Stewart, History of Norfolk County, Virginia, and Representative Citizens, Chicago, Biographical Printing Co., 1902) 34, 54; John H. Gwathmey, Historical Register of Virginians in the Revolution, Soldiers, Sailors, Marines, 1775-1783, Richmond, Dietz Press, 1938) 577; Revolutionary War Service Records, (National Archives, Record Group 93, Virginia, Individual, Folder “N”).

The earliest written documentation of Nash’s verbal account of Flora’s actions at the Battle of Great Bridge unearthed to date appears in a manuscript document written by James Jarvis in 1846. [James Jarvis, Reminiscences of Events Which Were Precious [?] to the American Cause: The Battle of Great Bridge, Norfolk County VA, December 9th 1775, and The Attack and Defense of Craney Island, Norfolk County, June 22nd 1813; also a “Six Months Tour (Portsmouth, Virginia, February 22nd, 1846, Manuscript. James Jarvis Reminiscences, Special Collections Research Center, Swem Library, College of William and Mary.) 13-14.]

“Captain Thomas Nash, late of Gosport, Virginia, was one of the faithful and conscientious soldiers who fought at the Battle of Great Bridge. In that battle he was slightly wounded in the hand. Captain Nash was well known as an honorable man. I knew him well. To honor his memory for his virtues, his patriotism, his Charity his Manners I partly write this note. In his Manners he was the “Old Virginia Gentleman.” Capt. Nash has been dead many years, long before I had ever seen any of quotations or letters preceding these remarks [referring to the account in the Virginia Gazette (Pinkney), December 20, 1775, PG. 3.].

“I will here relate one or two reminiscences which Capt. Nash was fond of telling whenever the subject was on the carpet. “That at the Battle of the Great Bridge, Billy Flora was the last sentinel that came into the breast work, that he did not leave his post until her had fired eight times. Billy had to cross over some loose plank to get to the breast work and had got some distance over when the idea struck him that it would be well to go back and pull the plank over on his side, which he did, stopping the headway of the enemy. And this he did amidst a shower of bullets.”

Jarvis (b. ca. 1790) clearly knew Thomas Nash well. He probably knew Billy Flora also, if not personally, at least by reputation.

The earliest published account is found in William Maxwell (ed.), The Virginia Historical Register and Literary Companion for the Year 1853, (Richmond, McFarland & Fergusson, 1853) 6: 5:

“Billy Flora, a colored man, was the last sentinel that came into the breast work, and that he did not leave his post until he had fired several times. Billy had to cross a plank to get into the breast work, and had fairly passed over it when he was seen to turn back, and deliberately take up the plank after him, amid a shower of musket balls. He probably was the very sentinel who is mentioned in the account as having fired “eight times.”

A note to this entry attributed to the editor’s “collector” (initialed “J.J.”), which repeats almost word for word the passage from James Jarvis’s Reminiscences, affirms that the “collector” was James Jarvis and that the account was based on his Reminiscences.

[22] Casualty reports clearly indicate that at least some of the Patriot defenders were firing buckshot. In addition to Fordyce with 11 or more wounds:

A corporal “… has seventeen balls through him” “JD” to the Earl of Dumfries

John McDonald, a marine from HMS Kingfisher “… departed this life of 11 wounds …” [Journal of H. M. Sloop Kingfisher, Captain James Montague, 9 December, 1775 (National Archives, UK, PRO, Admiralty 51/506) in Clark , Naval Documents, 3: 40.]

“Edward Villis, in the Thigh, Arm & Belly, Ball lodged in his Bowels, judged Mortal. … Saml. Hale, in the Shoulder, Side, both Hands with fractures, no Balls lodged. … Geo. Tilley, in both Thighs, in 5 places, one Ball lodged, no fracture.” [Report of Dr. William Browne, included as fifth enclosures of letter from “Colonel William Woodford, On the Virginia Service, to The Honble The President of the Convention at Wms:burg, with Enclosures, Great Bridge, Decemr, 10th, 1775 in Robert L Scribner and Brent Tarter (eds.), Revolutionary Virginia, The Road to Independence, Vol. V, (University Press of Virginia, 1979) 5: 102.]

[23] “Lieutenant Travis, who commanded in the breast work, ordered his men to reserve their fire until the enemy came within the distance of fifty yards.” Virginia Gazette (Pinkney, December 20, 1775) 3. A surveyed map of the Great Bridge area (Stratton, “Plan of the Post at Great Bridge …”) shows the causeway crossing a small stream about fifty yards from the site of the Patriot fortification. The bridge over that stream would have made an ideal range marker.

[24] “JD” to the Earl of Dumfries. John Burk says that Fordyce was struck by 14 balls. Burk, The History of Virginia, 442.

[25] Return of the Killed and Wounded of a Detachment of His Majesty’s 14th Regiment of Infantry at the Great Bridge, Virginia, 9th December 1775, signed by Captain Samuel Leslie, included as an attachment to Dunmore to Dartmouth, Dec. 13 1775, (PRO, CO 5/1353.)

[26] Woodford’s main body was at morning formation, fully armed and accoutered, in camp ~¼ mile from the Patriot breast work. Woodford would have gotten his men in motion either at the sound of the first volley or when a messenger from Travis reached him with news of the attack, whichever came first. At a brisk march, it would have taken his main body no more than five minutes to cover that quarter mile. By the time he reached the breast work the battle was, for all practical purposes, over.

[27] “… Colonel Woodford very prudently restrained his troops from urging their pursuit too far.” Virginia Gazette (Pinkney, December 20, 1775) 3.

[28] With the exception of a two week raid by Admiral Sir George Collier in May of 1779 (which caused immense damage), there was no organized British presence in Virginia until the arrival in January of 1781 of a force of 1,600 British under the command of Benedict Arnold.

[29] In 1776-77 Virginia sent 15 regiments to Washington’s army, more than any other state except Massachusetts, which also sent 15 regiments. In addition, Virginia provided 4 “additional” regiments, 17 independent companies, 2 artillery regiments and 3 cavalry/dragoon regiments. Sanchez-Saaverda, Guide, 16-38.

An analysis of the returns for the Continental Army shows that between 10% and 35% of the troops available to Washington from 1776 through 1780 (when most of the Virginia line was captured at Charlestown) were Virginians. Lesser, The Sinews of Independence.

In May, 1777, Virginia troops constituted more than a third of the Continental Army (3,561 of 10,003). “A General Return of the Continental Forces…Under the Command of His Excellency General Washington, May 21, 1777” Record Group 93, National Archives, in Lesser, The Sinews of Independence. 46.

[30] No full account of the amount of materials and supplies sent from Virginia to the Continental Army is known. However an indication of the importance of Virginia in supplying Washington can be gleaned from the journal of an officer of one of the ships in Sir George Collier’s fleet during its two week incursion in 1779. “[In] the town of Suffolk, … Nine thousand barrels of salted pork, which were stored there for Washington’s army; eight thousand barrels of pitch, tar, and turpentine, together with a vast quantity of other stores and merchandise, were all burnt and destroyed, together with several vessels in the harbor, richly laden, … {emphasis in the original}” In addition to the above, he writes of the destruction of “ … a vast deal of … stores … that could not be embarked [upon departure of Collier’s force]… for want of vessels but might be sent by degrees to England, where it is much wanted; …” [Reported in Lithiel Town, “A Detail of Some Particular Services Performed in America (Journal of Collier and Matthews’s Invasion of Virginia),” Virginia Historical Register and Literary Notebook 4 (October 1851): 189, 193.]

[31] The importance of Virginia was belatedly recognized by the British. “The way which seemed most feasible to end the rebellion was cutting off the resources by which the enemy carried on the war … these resources were principally drawn from Virginia {Emphasis added}.” [Reported in Lithiel Town, Ibid: 185]

[32] The Battle of Great Bridge took place eight months after Lexington/Concord, six months after Bunker Hill, two months before the Battle of Moore’s Creek Bridge (NC) and seven months before the Declaration of Independence. Fewer than 300 men, both sides included, were actively engaged in the action, which lasted less than five minutes.

[33] A ”Pay Roll of the Company that was formerly Captain William Grimes [sic], deceased of 15th Virginia Regiment…” dated August, 1777 lists William Flora as a Private. National Archives, Revolutionary War Rolls, Record Group 93 and National Archives, Revolutionary War Service Records, Record Group 93, Virginia> 15th Regiment (1777-78) >334>page 42. Grymes’s company, the only company of the Virginia Line to be raised in Princess Anne County (Flora’s home county) was raised November 21, 1776. There is only one officer named Grymes/Grimes listed for Virginia for the entire war. Sanchez-Saaverda, Guide, 72.

[34] National Archives, Revolutionary War Rolls, Record Group 93 and National Archives, Revolutionary War Service Records, Record Group 93, Virginia, Individual, Surname starts with “F” at http://footnotelibrary.com (Revolutionary War Archives) Search: Flora, William, accessed 17 December, 2013. Only one William Flora (sometimes spelled Flory) was found in the National Archive records.

[35] In his affidavit dated July 16, 1806, Thomas Matthews, late Lieutenant Colonel of the 15th Virginia Regiment wrote “…I was well acquainted with William Florey, who belonged to the 15th Virginia Regmt. and was from Norfolk County that he served in the Continental Line until the siege of York or the close of the war … and was held in high esteem as a soldier.” Certification of William Flora’s Revolutionary War service, July 16, 1806, Virginia State Library. <http://image.lva.virginia.gov/Microfilm/Revolution/RW/009/00415.tif> (accessed 1/25/2011). An image of this affidavit is also in Sidney Kaplin, The Black Presence in the Era of the American Revolution, 1770-1800, (New York, New York Graphic Society, 1973) 20.

[36] Heinegg, Free African Americans of Virginia; James A. Garraty & Marc C. Carnes, American National Biography (New York, Oxford, 1999)8: 136-7.

[37] Affidavit of Thomas Matthews, late Lieutenant Colonel of the 15th Virginia Regiment dated July 16th 1806, and affidavit of A. Slaughter, Surgeon to the 9th Vrginia Regiment, 1776-1778; Certification of William Flora’s Revolutionary War service, July 16, 1806, Virginia State Library. <http://image.lva.virginia.gov/Microfilm/Revolution/RW/009/00415.tif> (accessed 1/25/2011).

[38] Jarvis, Reminiscences, 13-14.

[39] James A. Garraty & Marc C. Carnes, American National Biography (New York, Oxford, 1999)8:137.

[40] Jarvis, Reminiscences, 14.

5 Comments

Thank you for this thorough and interesting article on an unsung American hero. I also appreciated your argument as to why this “tiny” battle’s importance transcended the action of one cold December day.

This is a very thorough account of The Battle of Great Bridge, which is something I have been researching for several years now. This six month period leading up to the burning of Norfolk is an intriguing and oft overlooked period in the War for American Independence.

I drive over the spot where this battle took place everyday and hope that one day the visitors center will be complete. Billy Flora has all the hallmarks of an American legend, from his over the top performance at The Battle of Great Bridge, to his continued service through the Revolution and beyond. What makes his case even more remarkable is that just a month prior Lord Dunmore had issued his proclamation freeing the slaves of Virginia and even utilizing his own Ethiopian Regiment during the skirmish at Kemps Landing, how easy it would have been for Flora to side with the British despite being a freeman.

The story of Captain Fordyce is equally intriguing. He led a group of Grenadiers over that Great Bridge directly into a choke point of Rebel fire. It was this group of Grenadiers that took the bulk of the casualties, including Captain Fordyce himself. The Colonial contingent even buried him with full military honors (sorry for my lack of references, I’m typing this on a phone). The loses sustained by the 14th Regiment of Foot sent them back to England for nearly the duration of the war. That is a pretty devastating impact, though it must be noted that their numbers were already drastically depleted after a deployment to the Caribbean prior to the onset of hostilities in the colonies.

The Battle of Great Bridge is truly a remarkable moment from that crucible that was 1775 and was even contemporarily refered to as the “second Bunker Hill” (an exaggeration for sure, but strategically sound). I could go on and on but I will end with my thanks for this article and the work you do in Colonial Williamsburg, Mr. Fuss. CW is one of my favorite place in Virginia, if not the entire United Stated. If you ever ascertain the exact were about of Mr. Flora’s grave in Portsmouth, I think it would be fitting for a memorial.

Humbly,

Joe Kresse

Came across the following in the “Essex Journal” out of Newburyport, Mass, for 1/12/76:

“Extract of a letter from Col. Woodford, to Edmund Pendleton Esq; President of the Convention.

“Great-Bridge, near Norfolk, Dec. 20.

“I must apologize for the hurry in which I wrote you yesterday, since which nothing of moment has happened but the abandoning the fort by the enemy. We have taken possession of it this morning, and found therein the stores mentioned in the enclosed list, to wit, 7 guns 4 of them bad, 1 bayonet, 19 spades, 2 shovels, 6 cannon, a few shot, some bedding, part of a hogshead of rum, 2 or more barrels, the contents unknown, but supposed to be rum, 2 barrels of bread, about 20 quarters of beef, half a box of candles, 4 or 5 doz. of quart bottles, 4 or 5 iron pots, a few axes and some old lumber; the spikes I find cannot be got out of the cannon without drilling.

“From the vast effusion of blood on the bridge, and in the fort, from the accounts of the centries, who saw many bodies carried out of the fort to be interred, and other circumstances, I conceive their loss to be much greater than I thought it yesterday, and the victory to be compleat. I have received no late information from Norfolk of Princess Anne, nor yet fixed on a plan on improving this advantage, I have dispatched scouting parties, and from their intelligence, shall regulate my future operations.”

I would love to see a picture of Billy Flora. My grandson loves history. He and my husband went to the enactment of The Battle of Great Bridge today and was approached by the executive director about playing this character. Our family is very interested in Mr. Flora. Anything you can send me will be appreciated.

Thanks for the great article! I’d seen the diorama containing Billy when I visited the American Museum of the Revolution at Yorktown several years ago but not fully realized Billy’s participation. I’ve posted a link to your article at our 2nd Virginia Regiment (NWTA) page: http://www.2VA.org

Thanks again!

William J. Bahr

Author, “George Washington’s Liberty Key,” a best-seller at Mount Vernon.