Smallpox raged across the backcountry in the late spring of 1781 and both of the Refugee commanders, Elijah Clarke and James McCall, caught the disease. Clarke was out of action for a month while McCall never returned at all, having died from the disease in March. During his time in bed, Colonel Clarke put plans in motion to retake Augusta and the Georgia backcountry. He dispersed the regiment “into parties of 10 to 12 men each, so as to spread themselves over the settlements, and appointed Dennis’s Mill on Little River, for the place of rendezvous. When these small parties entered the settlements where they had formerly resided, general devastation was presented for their view.” The Georgia Refugees reacted with “resentment. Mercy to a Loyalist who had been active in outrage, became inadmissible and retaliative carnage ensued.”[1]

Second Siege of Augusta

The British commander at Augusta, Lt. Colonel Thomas Brown, tried to stop the uprising. He first sent a patrol of 25 regulars and 20 militia down the Savannah River to investigate interruptions in his supply lines. The Patriots, “attacked them, though superior in number to themselves, killed the officer and 15 of his men, and compelled the remainder to retreat precipitately to Augusta.” Having learned their lesson, the next time Brown tried to react with his Provincials, they deserted and “fled to the Indians” on the frontier.[2]

Not one to give up easily, Brown stiffened even further and led a patrol against the Patriots at Wiggin’s Hill where he killed 7 and wounded another 11. In that raid, a guide named Wylly gave Brown false intelligence in an attempt to lead them into a trap. “Brown turned him over to the Indians, who ripped him open with their knives in his presence, and tortured him to death.”[3] It was the only instance in which Brown actually admitted to having used his Indian allies to execute a prisoner.

Brown retaliated for the ambush by hanging at least 5 more men at Augusta but there was no stopping the Georgia Refugees. Always a loose outfit, their numbers now surged with all types of men who sensed victory over the Tories and came out to join the insurgency. A Colonel Dunn swept across the ceded lands above Augusta and murdered about 60 Loyalists. “Augusta was placed in a blockade until the middle of May.”[4] Brown was now trapped inside his two forts outside Augusta.

Colonel Clarke returned to the field around the 15th of May. His presence helped bring some order to the chaos but did little to stop the retributions. When Brown tried to send a detachment of regulars and Indians out for forage, Clarke countered with the infamous Patrick “Paddy” Carr who “lay in a thicket, near Mrs. Bugg’s plantation and attacked them; and following the example which had just been set for them by the enemy, they spared the life of none who fell into their hands.”[5]

In spite of Brown’s predicament in the forts, there was little Clarke and the Refugees could do against their defensive works. Clarke tried to rebuild an old four pounder “which had been thrown away by the British; believing it might be converted to use” but the lack of powder and ammunition rendered the piece virtually useless. As a result, the siege continued until the 23rd when Pickens and Lee arrived to reinforce the Refugees and help overwhelm the British in Augusta.

The story of the battle and taking of the forts is for another day, but is itself quite interesting and involved construction of a wooden tower that would allow riflemen to target men inside Fort Cornwallis. In what was probably their last fight as a regiment, Clarke and the Refugees withstood a furious sally by Brown to break free of the siege. Unable to get out, Brown finally surrendered and the 2nd Siege of Augusta ended along with the last British rule in the Georgia backcountry.

Murder of Grierson

With the surrender of Brown and his troops came the problem of securing prisoners that many of the Georgia Refugees found personally repugnant. As the overall commander with a very legitimate fear that Clarke’s men lacked discipline, Lt. Colonel Henry “Lighthorse Harry” Lee placed Brown and the other officers “under a strong guard of Continental troops.” Even with the guard’s presence, a young man named McKay, whose brother had been executed, “sought an opportunity of putting Brown to death. His attempt was stopped by the guards. However, another prisoner, the Loyalist militia commander James Grierson, was not so lucky.

James Grierson was a local Loyalist who had lived in the Augusta area for a number of years before the war. The British investigated Grierson early in 1780 and then commissioned him a Colonel of militia in the Georgia backcountry above Augusta. Very influential, he even advised Governor Wright on choices of magistrates for the area.[6] Unfortunately, the war had been costly for Grierson; he lost his wife, daughter, son, and a brother who was “shot dead by rebels.”[7]

Perhaps motivated in part by revenge over his prior tragedies or perhaps by the ordeal he endured with Thomas Brown, Grierson had been directly involved in the mass retributions and executions that ravaged the backcountry after the 1st Siege of Augusta. Among his specific acts had been the mistreatment of an old man named Alexander whose sons, Samuel and James, were both captains with the Georgia Refugees. Later, during the 2nd siege, “Browne and Grierson resorted to the inhuman expedient of bringing out on the platform a number of aged persons, the parents, relatives and friends of the besiegers, and thus interposing as a screen for his own men – a living screen. Among them was old Mr. Alexander, too far advanced in age to bear arms, or otherwise unite in hostilities.”[8]

According to the later report by Andrew Pickens, on June 6, a man “rode up to the door of a room where Col. Grierson was confined, and without dismounting shot him so that he expired soon after.” The killer “instantly rode off” and escaped before he could be identified.[9] Nineteenth century historians James McCall and Joseph Johnson both followed on along and reported the killer as “one of the Georgia riflemen”[10] or “some one, at that time unknown.”[11] On the other hand, was Pickens really being sincere in his report to Greene?

The British clearly did not think so. Governor Wright said that Grierson was “basely murdered in the very midst of Rebel troops; a sham pursuit was made for a few minutes after the murderer, but he was permitted to escape.”[12] As to the identity of the shooter, Thomas Brown wrote a more detailed description of the events. A man “named James Alexander, entered the room where he [Grierson] was confined with his three children, shot him through the body, and returned unmolested by the sentinel posted at the door, or the main guard. He was afterward stripped and his clothes divided among the soldiers, who, having exercised upon his dead body all the rage of the most horrid brutality, threw it into a ditch without the fort.”[13]

Unfortunately for the Americans, when looking into the record a bit further, it does appear that Brown may be correct as to just who shot Grierson. In his memoirs, Tarleton Brown (not to be confused with Loyalist Thomas Brown) said that it was Captain Alexander who shot “Grierson for his villainous conduct in the country.” Additionally, two pensioners from Georgia, James Young and George Hillen, both identified Grierson’s killer in their accounts. “The next day after the surrender of the Forts, Colonel Grierson was killed by a gun fired by on James Alexander as was reported at the time.”[14]

As if killing Grierson weren’t enough, another shooter managed to wound an officer named Williams. At that point, Lee and Pickens decided to send Brown and the remaining officers to Greene who was engaged in a similar siege across the Savannah River at Ninety-Six.[15]

After the fall of Augusta, the focus of military operations in Georgia moved downriver to Savannah. The Georgia Refugees sort of fell apart as civil government was restored. Most of the officers and men received promotions and official commissions in new state or militia regiments. Elijah Clarke became Brigadier General Clarke and continued to lead the backcountry Georgians along the frontier for a number of years. Not only did they war with the Indians but a great many Loyalists had gone to live beyond the frontier and rounding them up took much of Clarke’s time.

A Few Closing Thoughts

No official regiment known as the Georgia Refugees ever existed. When government in Georgia collapsed, these men simply refused to surrender and carried on as an insurgency. They played key roles in the victories at Musgrove’s Mill, Blackstock’s Plantation, Cowpens, and 2nd Augusta. Even their defeats at 1st Augusta and Long Cane are significant events that went a long way toward convincing the British to give up their attempt to maintain control of the southern colonies. While certainly no single regiment or militia commander can claim to have single-handedly saved the war, in my opinion at least, the Georgia Refugees fought as many battles and had a greater impact on defeating the southern strategy than any other single regiment in that theater of operations.

So, why are the Georgia Refugees almost completely unknown to history? The answer might be their lack of definition as a unit or possibly that Elijah Clarke is thought to have been illiterate and therefore left almost no record of their activities. The problem could also be the very nature of the southern campaigns. Such a messy place overall that few go to the trouble for a real understanding of events there. However, there may be yet another answer. Perhaps Elijah Clarke and the Refugees aren’t much written about because their exploits tended toward the dark side of things and many historians prefer a rosier view of the American Revolution. After all, how many want to imagine their personal heroes out hanging a few Tories or burning out whole families in a purge of anyone who dared voice political opposition to the Whigs? However, there is real truth found in the story of the Georgia and South Carolina backcountry. These states were not prevented from joining East Florida as British colonies simply by virtue of Nathanael Greene’s nicely performed campaign of delay against Cornwallis. The men of the back country, the volunteer militia of the Refugees (and a few other regiments) won the war of hearts and minds in southern states. Unfortunately, they did it by utilizing brutal tactics of murder and intimidation that Americans would actually like to avoid knowing much about. The famous southern strategy employed by the British was based upon a belief that a majority of southerners would actually prefer to remain with the crown. Today we enjoy chuckling at how wrong they were and how the people of the backcountry rose up in defiance of that notion to send Cornwallis packing. But my research has never really proved the British wrong. Instead, I have tended more towards a view that the Whig population, even though surely a minority in 1775 and probably still short of majority in the summer of 1780, carried the revolutionary war in the south by several years of harsh oppression followed by a violent purge of the remaining Loyalists from 1781 to 1782.

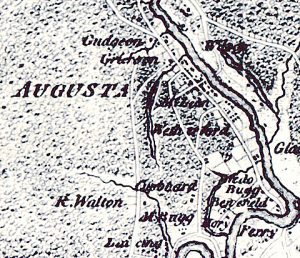

[FEATURED IMAGE AT TOP: Scarce regional map of Georgia, 1764, from Nicholas Bellin’s La Petit Atlas Maritime. View full size. Extends from Port Royal and Augusta in the North to Saint Augustin in the South. Shows a number of early roads, Fort More, Ft. Argyll, F. du Roi George, F. Diego, F Picolata, Ebenezer and Old Ebenezer, Savannah, Fort S. Georges, etc. The 1738 Georgia-Florida Boundary line is also shown. One of the earliest obtainable maps of the region. Source: Barry Lawrence Ruderman Antique Maps, raremaps.com]

[1] Hugh McCall, History of Georgia (Savannah, GA: Williams, 1816), 2:362.

[2] McCall, History of Georgia, 2:366.

[3] McCall, History of Georgia, 2:366; see also, Thomas Brown to Dr. David Ramsay, 25 December 1786, in George White, Historical Collections of Georgia (New York: Pudney & Russell, 1854), 617. Brown admitted that he turned Willie over to an Indian Chief for execution but only says the man was tomahawked. Brown indicates this as the only Indian outrage committed by any Indians under his command. His claim is actually a bit suspect in light of the Patriot claims of regular outrages by the Indians along the GA frontier and also the incidents following the 1st Siege of Augusta. At that time, torture and killing of prisoners was not uncommon practice among Native Americans and there would seem to be little evidence that Thomas Brown was more successful than other commanders at stopping these practices.

[4] McCall, History of Georgia, 2:366.

[5] McCall, History of Georgia, 2:368.

[6] Mary Bonderant Warren, Georgia Governor and Council Journals 1780 (Athens, GA: Heritage Papers, 2009), 26.

[7] James Grierson, Grierson Family Bible, reprinted in Georgia Loyalist Claims,

[8] Joseph Johnson, Traditions and Reminiscences, Chiefly of the American Revolution in the South (Charleston, SC: Walker & James, 1851), 359.

[9] Andrew Pickens to Nathanael Greene, 7 June 1781, in Richard K. Showman, The Papers of General Nathanael Greene vol VIII, (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 1994), 8:356.

[10] McCall, History of Georgia, 2:374.

[11] Johnson, Traditions and Reminiscences, 357.

[12] James Wright to Shelburne, 28 February 1782, in Warren,Georgia Governor and Council Journals 1780, 145.

[13] Brown to Ramsay, 25 December 1786, in White, Historical Collections of Georgia, 617.

[14] James Young, Pension Application R11977, transcribed by Will Graves, http://revwarapps.org/r11977.pdf; see also, George Hillen, Pension Application S7006, transcribed by Will Graves, http://revwarapps.org/S7006.pdf, which says, “A comrade named James Alexander killed Grayson [Grierson].”

[15] Pickens to Greene, 7 June 1781, in Showman, The Papers of General Nathaniel Greene, 8:356.

19 Comments

Wayne,

I have thoroughly enjoyed this series. I am researching the Refugees because I descend through one of them, Robert Hammock (Hammack) or Richmond and Wilkes Counties. I have been particularly interested in the contributions of his Refugee family to the Cause.

I must challenge a couple of your assertions. Namely, “No official regiment known as the Georgia Refugees ever existed,” and “The answer might be their lack of definition as a unit or possibly that Elijah Clarke is thought to have been illiterate and therefore left almost no record of their activities.”

I have in my possession digital copies of four yellowed pages from a file box in a special collection at the University of Georgia Library. The note on the outside of the documents reads, “Return of Refugees Richmond County.”

The heading on page 1 reads as follows:

“A List of the Officers and Soldiers Who fled the Protection of the British and took refuge in Other States and did their Duty faithfully Under the Command of Coll Wm Candler from the 15th Septr 1780 Untill the Reduction of the British Troops in Augusta.”

The list was, apparently, compiled by Col. Wm Candler. It contains 63 names and a total summary of officers and men as, “1 Coll, 1 Maj, 3 Captains, 5 Lieuts, 65 Privates.” It is broken down into three separate companies.

The list is certified and signed by, “Elijah Clark – Col. Commandant of Refugees.” This certification is n a different handwriting from the remainder of the document.

The back of the second document reads, “List of Refugees who Hid with Col Candler 15 Sept 1780.”

This list confirms that there was an official, organized regiment of Georgia Refugees. It also seems to indicate that Elijah Clarke was, indeed, literate.

Have you seen these documents?

Would you like a copy?

🙂

I would love a copy of the list! Are there any Dickeys. Braggs, Burkes, Mills, Bonnells, Lovetts or Boyettes on it?

Is it possible to get a copy of this list as well? My ancestor, Daniel Jackson, was also a refugee. I obtained copies of the land bounties given to him by Elijah Clarke and the grants clearly show that he was a “refugee”. I think I may also be related to the Robert Hammock refugee soldier mentioned as well – there was a later marriage between a Robert Hammock and a Combs and my gr-gr grandmother was a Combs. All from Wilkes and Oglethorpe Counties.

My email: sigmaindgrp at msn.com

Thanks.

Just stumbled across this article. My patriot great grandfather Daniel Sikes 1742-1788 is credited as being a GA “Refugee Soldier”. He was killed after his return by Indians in 1788 in Washington Co. near Williamson’s Swamp. I have seen him referred to as Lieutenant Daniel Sikes, but I have not found any proof of that rank or title. I’m not sure if anyone in this article comment thread will continue to get notifications, but I would love to know if Daniel appears on any lists or documents referred to in the comments here. If so, could someone please forward me the info? I would truly appreciate it. Thanks!!

I wonder if a copy of this regiment is available. I am looking for information on LT Joel Doss who is said to have been a refugee. Thank you for any help you might offer

Geoff,

Delighted at your interest in Elijah and the Refugees. I would certainly not wish to quibble over semantics but I think we are using the term, ‘official’, a bit differently. At the time the refugees refused parole and begin to band together the civil government of Georgia had completely collapsed and most of the militia structure was also gone. The men came from different counties (although many were from Wilkes) and simply volunteered on an individual basis to join the regiment. To me, that is not an official regiment. However, if you want to rely on the existence of a command structure (militia generally chose their own officers and the Refugees seem to consider themselves militia) and a duty roster with identifiable soldiers, then I would certainly go along with your assessment. However, one other item I might point out is that Elijah and the Refugees were in South Carolina skirmishing with Dunlap two months before Candler’s call to arms in September of 1780.

I would love to see digital copies of any Clarke letters. As cited in the article, there are also a couple of Clarke letters elsewhere. One in the Cornwallis Papers and another in the pension file of Major Cunningham. I do not know much about the conclusion concerning Clarke’s literacy. I am no handwriting analyst and don’t have an opinion about the letters being written by Elijah or by an assistant. My email is ly******@ya***.com if you wish to forward the documents.

I have also recently done some work (it is continuing) in the Draper manuscripts and noticed a reference to many Elijah Clarke letters having been lost in a fire in 1845.

In keeping with my latest research on Elijah, I will leave you with a couple of delightful quotes (even though totally biased) from his Grandson.

“His determination & courage never quaverd. He was either victorious or, personally disabled in every battle. The confidence he inspired was universal. The inhabitants of that region reposed upon their opinion that he was always ready for service.”

And this from the son of Elijah’s friend, Micajah Williamson, “He [Micajah] spoke of him [Clarke] as cool, methodical and undaunted. He spoke of Genl. Clarke as heroic, never going to a battle without receiving physical wounds & as an intense sufferer from physical pain. He spoke of them [Elijah & Micajah] as a rare combination of men who aided one another so that each supplied what seemed to be necessary to efficient command so that together they were perfect.”

No mention of the Battle of Kettle Creek, a battle involving Elijah Clarke and the Georgia Refugees. I enjoyed the story very much.

Good morning David. Kettle Creek was fought while Georgia’s regular militia regiments remained intact. The Refugees came out of the collapse of state government and parole of most citizens occurring in June 1780. Elijah was certainly on hand with many of the same men but they were the Wilkes District militia at Kettle Creek.

Wayne,

This unit is, indeed, one of the more fascinating to me in all of the Rev War. I was absolutely thrilled when I discovered an ancestor in its ranks.

The roster of soldiers that I have is actually not by Clarke (though he has a paragraph of “certification” at the end of the roster.). It appears that this was a list complied by Candler of the men who were with him at the first Siege of Augusta and “hid” with him and Clark after that date (15 Aug 1780). I am assuming, I hope correctly, that this means they were all part of the mass evacuation / exile to Watauga a few days later.

I have managed to procure every document that I can find for my ancestor, Robert Hammock (of Wilkes County). His bounty documents clearly identify him as one of the “Refugees,” and seem to confirm his appearance on Candler’s list. His bounty certificate was actually signed by Benjamin Few, not William Candler, which has been a matter of curiosity to me. This, it seems, confirms your well-made point about the loose, unofficial nature of this militia group. Subsequent to the act of Sept 20, 1781, my Robert Hammock returned to Georgia and filed his land claims in Wilkes County (presumably upon land that he had settled prior to the war, before displacement).

I am away from my office this morning, but upon my return this afternoon I will be happy to forward you a copy of Candler’s list (4 pages). I am certainly no analyst of handwriting, either. But it seems to me that the paragraph attributed to Clark (no “e”) is in a different style from the remainder of the document.

I’m sure that you will enjoy examining it …

Blessings.

Geoff,

I noticed your reference to the Clark (no ‘e’) and it reminded me of the pension file of John Cunningham. That file has a number of transcriptions of Elijah Clarke documents done by Will Graves. I notice that several of them have ‘Clark’ while several others have ‘Clarke’. I feel certain Mr. Graves transcribed each according to the signature.

Interesting.

http://revwarapps.org/w6752x.pdf

Geoff,

Pleased to meet you through the website. I find the roster very interesting. Particularly, as I sit back and ponder its significance, I think it goes to show that county militia regiments remained somewhat important even during the period when civil government collapsed in Georgia. I have pension application printouts on about 20 of Elijah’s refugees and I see they don’t appear on Candler’s list. I went through my notes in a quick scan kind of way and noticed they all seem to be from Wilkes County. Perhaps in truth, the men remained mostly within their existing regiments under their existing officers. I am reminded of Benjamin Few showing up at Blackstock’s and getting credit for commanding the GA regiments due to his seniority over Clarke. However, that doesn’t seem to be a problem any other time as Few’s men didn’t really travel with Clarke. (or at least Few doesn’t seem to have).

I have no idea about whether the Richmond County Men with Candler were also with Clarke on the exodus to Watauga. Sources indicate that Clarke had about 200 to 300 men recruited for the attack on Augusta at September 15. Evidently, part of these men were the Candler regiment. You might try looking at the roster and searching the names in the pension files to see how many gave summaries. The exodus appeared in about 20% of the pension applications for Elijah’s Wilkes County men.

Have you had opportunity to review the Draper manuscripts for info on Candler? A quick glance at a couple of items yielded me these tidbits. Don’t know how accurate they are:

“At the opening of the Revolution [Candler] took a disided part in favor of Collonies Raised a Redgment and equipted at his own expense (his Ridgement was called Minuit men). His property was confiscated by the British government his negroes taken to Savanoh by the British army and his houses plundered and burned and his wife and children driven to a swamp for safty whare they Resided in a Camp for several Months. He was seriously wounded at Brier Creek in GA toward the close of the war and never performed any further Military service. He represented Richmond County for several years after the war and died and is buried at his farm Known as fruit Hill in Columbia County 4 miles east of Mt Carmel in 1789.” D. G. Candler 12 Feb 1872

Mr. D. G. Candler later corrected himself somewhat with this addition:

“He was never seriously wounded as stated by me from family tradition. . . The service which he performed was mostly detached services on the Georgia side of the river. He took part in the fights at Kings Mountane, Blackstocks farm, Bryer Creek and many other battles and skirmishes mostly with the Tories to whome he was said to be a Terrore. During the war he was outlawed by the British athorties together with 151 others prominent whigs provided they did not appear and take the prescribed oath in a given time. He failed to comply and while the british held savnah They sent a force and plundered and burned his houses and fences and caried off his negroes 43 in number and kept them until they evacuted the place, when the negroes being turned loose all come back to there master except two who had died while captives . . . ”

I didn’t run across any mention of Candler being with Clarke on the exodus to Watauga but I noted the part about living in a swamp for several months. This may be an indication that Candler remained in Georgia during the occupation and the time of retribution by Brown and Grierson following 1st Augusta.

Mr. Lynch,

Candler & his entire family fled toward the Watauga Settlements with Clarke. Clarke had been wounded and was not able to fight. The Georgians were in the vicinity of present day Rutherfordton, NC when they got word about Ferguson. Clarke assigned Major Candler to lead the small contingent of Georgians to aid in what would be the victory at Kings Mountain. There were 33 Georgians present at the battle including Major Candler’s son, Henry Candler.

Draper documents this in his writings. The service of both Candler’s has been fully documented by the NSDAR.

According to Georgia Governor, Allen Daniel Candler, based on his own research, Candler was known as the Colonel of the Refugee Regiment.

This may have been a term of honor from his men, or it may have come about as a way to identify Candler’s men.

Can you check the list for Robert Jarrett. He was identified as a refugee soldier in family lore. Can you also check for Charles Kennedy who married Robert Jarrett’s widow.

Thank you,

Carol Kennedy Hightower

Found a reference for Devereaux Jarrett who was an assemblyman in GA. He was named in the Disqualifying Act of 1780. No Robert. Several Kennedy references but none for Charles.

Thank you for your excellent article. I am searching for information on my fourth great grandfathers, William Daniell and David Elder, both were awarded land grants in Clarke County which later became Oconee County. William Daniell’s headstone has Georgia Troops on it. It was thought he fought at Kettle Creek but there is very little proof. Thank you for your time, Susan Ryan

I know Joseph McCormick was listed as a”refugee”, aKing’s Mtn. soldier, at seige of Augusta, etc. He has draws on the GA lottery from Elijah Clarke, but I do not know if he was part of Candler’s troops?

Dear Wayne,

My 6th Great Grandfather, Maj. John Shields, was shown “killed at the siege of Augusta” and the date of his death as 24 May 1781 – yet I can find no information whatsoever as to how he died. Chandler’s memo on his pension application notes “lost his life…” whereas he cites other deaths as “Fell” etc. I really want to know how he died. Has his name ever appeared in your research, and if so, can you tell me what you found or cite the reference? Greetings from a fellow Texas – Frank Brown, Dallas

Thank you for an informative article. I am searching for information on a sixth great grandfather, Peter Perkins. He was granted 500 acres of land in St. Paul’s Parish (Richmond County) in Dec. 1768, granted 200 acres in Wilkes County in 1788, and in 1784 granted 287 acres in Washington County. I’m unclear if he was part of any militia – let alone the Georgia Refugees. Although not a Quaker, he was part of the Wrightsborough Settlement. His Bounty grant said “hath faithfully done, his duty from the time of passing an act at Augusta, to wit, on the 20th of August 1781 until the total expulsion of the British from this state”

Please advise if you see a Peter Perkins on the Georgia Refugees list.

I am interested in any listing that might be available.

I am searching for a James Martin who suddenly surfaces in GA during and after the Revolution. It has been cl;aimed that he was born in Barnwell District SC in 1756, and that he was a Dunker preacher who became a wealthy landholder and planter in Bryan County. It is believed that he may have been a SC Militia member who joined the GA Refugees about 1780 or so. There were multiple men of the same name, making it difficult to sort them without more detailed information. It has been claimed that he was involved with the Lumbees of NC in his early years, but valid proof is lacking, making those claims supposition.. From later documentation, I know that he was literate and fathered twelve or more children with two wives. There is no evidence that he was the Militia Surgeon/Doctor.