When it comes to Pennsylvania military hospitals during the Revolution apart from Philadelphia, Bethlehem has received a great deal of (appropriate) attention by scholars mainly because (1) it became the new Headquarters of the Hospital Department under Dr. Shippen, and (2) shortly after wounded arrived, the town began to see a very high mortality rate. In the entirety of its service (until 1778), it is estimated that between 500 and 1,000 soldiers in the care of the Continental Hospital in Bethlehem succumbed to disease and neglect.[1] These men are currently buried in a mass grave, which was once just farmland, overlooking the Monacacy Creek a few hundred yards away from where the main hospital building still stands to this day.[2] The role of another important army hospital in Easton is often ignored. Many presuppose that Bethlehem was the only place where large amounts of soldiers lost their lives while Easton is rarely, if ever, mentioned as a place of suffering. In reality, it appears that more Continental soldiers died at Easton than on most of the Revolutionary War battlefields. It doesn’t just end with Continental soldiers either; Easton is also where countless British prisoners of war found their final resting place.

In the winter of 1776 the population of Easton numbered around 450 people.[3] Surrounded by a landscape that Henry Dearborn, an officer in the New Hampshire Line, called “very poor and barren…such as will never be Inhabited,”[4] Easton wasn’t much to look at. Tories abounded in the county of Northampton, of which Easton stood as capital, and disaffected members of the community were constantly being hauled through the Court House at its center and then to the county jail about a block away. But in spite of its small population, with its unimpressive surroundings, Easton had a great deal of strategic value. It had one of the few ferries for miles around that crossed the Delaware between Pennsylvania and New Jersey, and it had an abundance of warehouses that General Washington would use to store military arms, ammunition, and supplies. It also happened to be a major thruway between New York and Philadelphia. These attributes were noted early on by Patriot leaders and military officials alike.

Sergeant John Smith of Rhode Island stayed at Easton on 16 and 17 December 1776, and made some small notes about the town in his journal. The inhabitants, he wrote, “were all Dutch and not the kindest in the world.” Smith had come in by ferry at night on the 16th, and he and his company knocked on doors to ask for a place to warm up as snow had fallen outside and “we could not pitch our tents the ground was froze so hard.”[5] He spent that first night shivering in the cold. Smith tried again the following night to find shelter, warmth, and comfort “amongst the houses But had some Dificulty their Being no Room for Us.” Luckily, he was able to find a place to hang his hat, though he and his companions took advantage of the home owners’ hospitality (which might be why they were none too kind in the first place).[6]

The reason shelter eluded the Sergeant was not due to the Eastonian’s sour dispositions; Smith wasn’t joking when he wrote that the residents had no more room. He and his company were among 4,000 troops under the acting command of General Sullivan (previously under General Lee, who had been captured a few days earlier) that arrived in the town over the course of his two-day stay, and when he left some 900 more men under General Gates and an additional 3,000 men under General Heath were expected to come through shortly after.[7] These numbers do not include the hundreds of camp followers. Among the living and healthy (well, as healthy as they could be) were British prisoners of war, and hundreds of sick, wounded, and dying.[8] One can only imagine the strain that put on a community with less than 100 buildings within the town’s whole radius (that includes the outhouses—and with few of those around, where exactly do 4,000 men relieve themselves?).

As always, context is important. Since August, Washington had been retreating from his defeat in New York; he’d crossed over the Hudson into New Jersey. From Newark to Trenton he had been harassed by Cornwallis, leaving behind many of the sick and wounded; a hospital was set up in Hackensack and then moved to Morristown almost immediately. While originally welcomed there by the community as a means to protect them from the British, an outbreak of smallpox, spread by the sick soldiers at the hospital there, caused the deaths of over 200 men, women, and children of the general population. One might see how that would make the community a little testy and uneasy.

By late November, Dr. William Shippen, Jr. was given directions by Congress to take over the hospitals, but Shippen wrote to Washington that 2,000 men were scattered around New jersey in terrible conditions due to a disagreement with Dr. John Morgan (in charge of the casualties on the other side of the Hudson) over who should be caring for them.[9] In reply, Washington gave permission for Shippen to use Morgan’s stores to establish a series of hospitals in Pennsylvania, to get the casualties away from where the British might capture them.

Shippen, taking over entirely for Morgan, moved quickly to locate suitable places for Continental hospitals in the interior parts of Pennsylvania; one large hospital in Philadelphia and one at Bethlehem were initially found, being far enough away from the British that the wounded and ill could be protected. By 4December, the Moravians at Bethlehem were given orders to allocate buildings for the wagonloads of invalids expected to arrive within the week. They immediately began preparing for their arrival, but as one Moravian diary notes, Easton ended up with the bulk of the invalids:[10]

“Dr. Shippen and Surgeon John Warren were so pleased with our willingness that they made arrangements to have the greater part of the sick quartered in Easton and Allentown. They informed us, that the hospital at Morris town, from whence they came, contained one thousand patients; of these five hundred will be quartered in the Forks [Easton], – about one hundred and fifty in Bethlehem.”

The remaining invalids were split and sent on to Allentown and Philadelphia.[11] On 8 December, the same day Washington had crossed the Delaware into Pennsylvania, and just a few days prior to the arrival of Sergeant Smith’s Rhode Island regiment at Easton, Shippen penned a letter to Washington from Bethlehem that, “With much difficulty & a small Loss I have got all the sick, except 20 who were too ill to remove, to Easton, Bethelem & Allenstown, where in a few days I flatter myself they will be as happy as sick soldiers ever are.”[12] In case you were wondering, yes, he flatters himself in nearly every letter.

Over the course of the winter and through the spring, the hospitals remained active. Every hospital report we have demonstrates that death tolls were exceedingly high during this period. Bethlehem lost a total of 110 soldiers between December and March. Unfortunately, manuscript evidence covering the losses at Easton during this winter are missing, though it is not implausible that they were comparable to Bethlehem, if not much worse considering the number of sick soldiers in the city at the time. By April, the number of dead in Philadelphia was even more staggering. John Adams told his wife about his solemn visit to the graveyard:[13]

“I have spent an Hour, this Morning, in the Congregation of the dead. I took a Walk into the Potters Field, a burying Ground between the new stone Prison, and the Hospital, and I never in my whole Life was affected with so much Melancholly…. The Sexton told me, that upwards of two Thousand soldiers had been buried there, and by the Appearance, of the Graves, and Trenches, it is most probable to me, he speaks within Bounds.”

Two causes for the high fatality rate are clear from the records: (1) smallpox and (2) epidermic typhus. Smallpox was everywhere and methods were not put into place quickly enough to isolate the infected and inoculate the healthy troops. In fact, inoculations were against Washington’s own General Orders and they wouldn’t occur army-wide until late February 1777 (and at least one prior attempt to inoculate troops had led to jail time for one surgeon), at the behest of Shippen.[14] Epidermic typhus, spread by lice, killed more after smallpox inoculations than anything else. This will be explained in a moment.

By mid-spring, the Continental Hospitals were nearly emptied of soldiers and they began to close. Washington’s successful attacks on Trenton and Princeton had dissuaded the British from making any major advance from New York. This stalemate gave way to several small skirmishes known as the Forage War, but no major battle took place and so there was no great need for large institutions to care for the wounded. With the passing of winter weather and the inoculations against smallpox going successfully, troop morale was raised and the smallpox-free army gave a much-needed boost to Washington’s recruiting efforts. But the Hospital at Easton was not yet done—war was coming to Pennsylvania.

By the fall of 1777, General Howe had begun to hint that he would be landing troops near Philadelphia, prompting Washington to build up defensive fortifications and prepare for an invasion which came in late summer. Washington’s defeats at Brandywine and Paoli in September, the capture of Philadelphia, and the defeat at Germantown in October meant that there were lots of wounded soldiers in need of immediate care. The most seriously wounded were generally kept at field hospitals near where the battle happened. But those that could be transported had to go somewhere and Philadelphia was no longer an option.

A letter was dispatched from Trenton at the hand of Shippen, dated 18 September, informing the residents of the Lehigh Valley to prepare to receive wounded.[15]

“It gives me pain to be obliged by order of Congress to send my sick & wounded Soldiers to your peaceable village—but so it is. Your large buildings must be appropriated to their use. We will want room for 2000 at Bethlehem, Easton, Northampton, &c, & you may expect them on Saturday or Sunday. I send Dr. Jackson before them that you may have time to order your affairs in the best manner. These are dreadful times, consequences of unnatural wars. I am truly concerned for your Society and wish sincerely this stroke could be averted, but ’tis impossible.”

By 21 September, sick and wounded men from Bristol were already streaming into Bethlehem and Easton. They entered into the towns “attired in rags swarming with vermin.”[16] Just slightly over a month later, on 22 October, the Brethren’s House in Bethlehem had been filled to capacity. According to a diarist:[17]

“A number of wagons with sick from the army arrived, but as no accommodation could be furnished, they were forwarded to Easton. Upwards of 400 are at present in the Brethren’s House alone, and 50 in tents in the garden back. The Surgeons refuse to receive any more into the large building.”

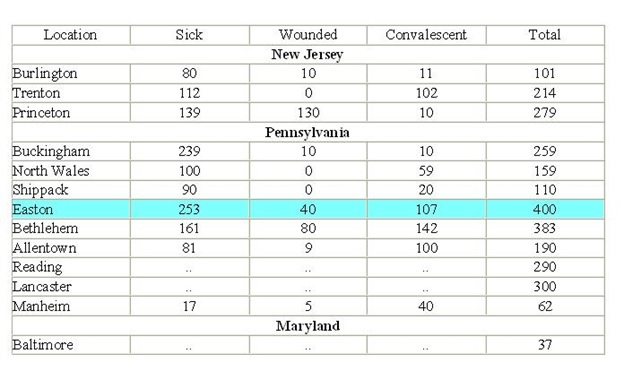

Around 24 November 1777, we find the first hospital reports, though some are still missing:[18]

From this chart, we can see that Easton had more patients than any other hospital facility that filed reports during the month of November—including Bethlehem and Reading. More carts would continue to flow into Easton and through Easton to other locations as the winter months continued.[19]

While all this was happening, Easton was also contending with the supplies flowing in from Philadelphia; hundreds of wagons were moving everything from clothes to gun powder, in order to prevent their capture by the British. British prisoners of war under armed guards were also marched into town, many of whom were malnourished and exhausted from being moved from town to town with little food and water.

Daniel Clymer, the Deputy Commissary of Prisoners, traveled to Easton in mid-December 1777 and noted that 60 prisoners of war were confined in the county jail.[20] Easton would provide them no comfort, as all the blankets and extra clothes—what little there was to find—were being used to help the sick and wounded Continental soldiers in the hospital. Like the Continental soldiers on parole in New York, the prisoners at Easton often starved or saw themselves catch ill.

Lewis Nicola, commanding the Invalid Corps (men too severely wounded for front line action but still able to handle light duty), stationed 25 of his men at Easton to guard the POWs in town and the hospital in mid-January, 1778.[21] His own troops were, according to him, “almost naked & besides what they suffer from the severity of the weather the appearance of many of them is offensive to decency.” Given the state of his soldiers, it is understandable that he reported to President Wharton that:[22]

“The English prisoners in goal are very sickly; of the 40, eighteen were reported to me sick this morning, one of which is since dead, & two were buried yesterday, there are, as I am informed about as many Hessian prisoners, but I found them all at liberty.”[23]

He also made note in his letter that only two sentries guarded the goal upon to his arrival, one at the gate and the other inside the yard with the prisoners; he was astonished that none of the prisoners had been enterprising enough to overpower the guard, take their guns, and burn Easton to the ground. It seems that their sour condition, being sick and wanting of food and clothes, made them too weak to make any attempt for freedom.

A month later, around 25 February, Doctor Benjamin Rush—director surgeon of the middle department of the Hospital Department—sent a letter to General Washington informing him of his intent to resign his commission over a feud with Shippen. His concerns laid out, in detail, the actual horrors of the hospitals that he had visited and explained to a large extent the appalling underreporting of fatalities by Shippen and his staff in the previous months. He aptly made a point to inform the General that “This Acct will appear to be the more distressing when I add that the mortality was chiefly artificial, and not the consequence of diseases contracted at camp. Eight tenths of them died with putrid fevers [typhus] caught in the hospitals.” He presented Washington with several copies of letters he had received from staff at Bethlehem sent to him on 17 December (which would also indicate how poor conditions were at Easton, given they were all run by Shippen):[24]

“That a putrid fever raged for three months in the hospital—and was greatly encreased by the sick being too much crouded, and by their wanting blankets—Shirts—Straw—and Other necessaries for sick people.

That so violent was the putrid fever in the hospital, that 9 out of 11 Surgeons were seized with it one of whom died, that out of 3 Stewards 2 died with it and the 3rd narrowly escaped with his life, & that many of the inhabitants of the Village caught & died with the said putrid fever.

That there have died in this place 200 Soldiers (8/10 of whom with a putrid fever caught in the hospital) within the Space of 4 months.”

Rush made it clear that these incidents were not isolated just to Bethlehem: “Vouchers of the same kind have been collected from several other hospitals all of which tend to shew the negligence and injustice of the Director general, and of some of the Officers connected with him.” And while not mentioning Easton specifically, we can see how terrible the conditions were throughout the middle department region:

“I am not acquainted with the number of the deaths in all the hospitals in the department for these last four months. In Reading there have died 180—In Lancaster 120—In Princetown between 80—& 90—(60 of whom died in Decr & Jany). These returns are only from one fourth of the hospitals which have existed within the four last months. I think from the best general Accts I can collect, that the number of deaths in the hospitals from which I have obtained no returns, cannot amount to less than seven or eight hundred more [Easton included].”

Most disturbing were the letters that Rush cited from Shippen indicating that all was well. Shippen had written to Washington on 18 January, stating “I flatter myself it will appear that our sick are not crouded in any hospital, that their number is not much if any larger than in my last return—that very few die—that no fatal disease prevails & the hospitals are in very good order.”[25] Rush did not hold back, asking Washington plainly, “What consolation can be offered to the friends of those unfortunate men who have perished—or rather who have been murdered in our hospitals…?”

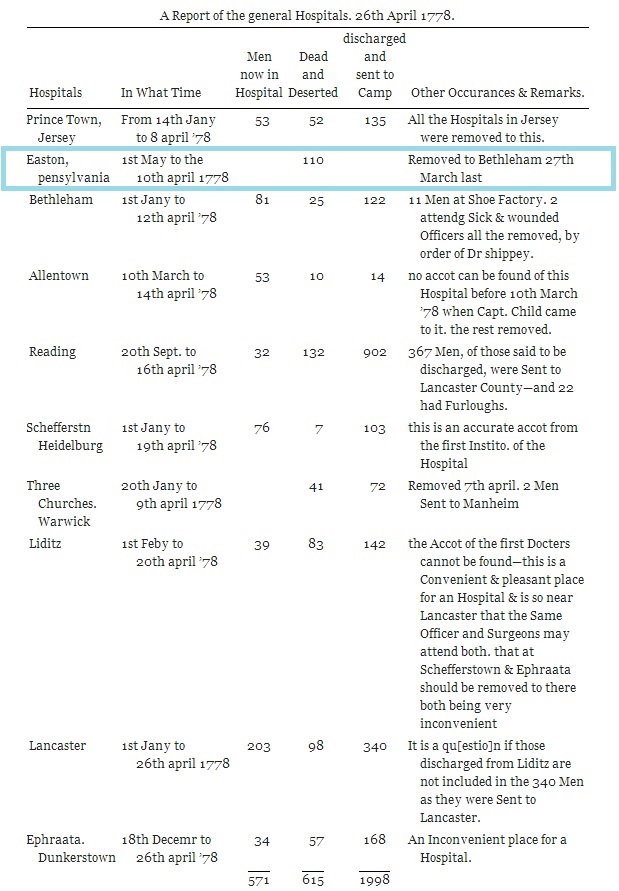

In March, the middle department began to close hospitals, one by one, as the war moved into the southern theatre. Easton’s hospital would close on 27 March, and Allentown’s shortly after that. A return was made of all the hospitals in April, and in it we find that the hospital in Easton reported that 110 patients had died.[26]

The dates given—1 May 1777 to 10 April 1778—are misleading; these are not the dates of the report (as the hospital had closed at the end of March), but rather the period for which the one report found would have been filed. Given that the remarks state that the hospital was removed to Bethlehem,[27] it is likely this was the last return made (all earlier returns seem to have been lost or were never filed to begin with), and so it also seems that they only list the number of dead (deserter totals were only relevant for the hospitals still open). These 110 soldiers would not be the last casualties of the war to find their end in Easton.

By the summer, Easton was again filled with Continental troops. General Casmir Pulaski and some of his Legion men were given orders to remain at Easton, though previously directed to Bethlehem. While there, his hussars tasked the British to do manual labor. At the same time, the prisoners who were not out working were confined to close quarters in the jail. Robert Lettis Hooper, Jr., wrote to his friend and colleague Elias Boudinot, Commissary General of Prisoners, on 13 June about the condition of the prisoners he was sending to him from Easton:[28]

“I have sent under the care of Mr Henry Shouse eleven prisoners of war; List inclosed—they are all that are left of the Brittish prisoners except one, who is too ill to move—Except the three persons that were cutting wood last Fall not one Man has attempted to escape—General Pulaski has enlisted 16 of the Brittish prisoners of War and detains them, & about thirty died since I rec’d your Orders to Confine them in a close Goal—I am collecting in the Hessians & they shall set out tomorrow but I think they’ll go reluctantly & I think will escape if they can—they wish to stay with us.”

However, more prisoners must have arrived shortly after; records indicate that a brawl broke out between members of Nicola’s Invalid Corps guarding prisoners and Pulaski’s Legion, in one of the craziest instances of the war (that I’ve come across). The events are rather confusing because according to all the depositions, it got violent and chaotic rather quickly. As happens when a fight breaks out, each side blamed the other (because ‘time out’ had not yet been invented as a means to deal with finger pointing).

Apparently, according to the first complaint lodged by the Invalids, two of the hussars under Pulaski were escorting a prisoner back to the jail and then struck the prisoner over the head in front of the Sergeant of the Guard (one of the Invalids). The sergeant demanded they cease their abuse. Well, that wouldn’t stand, because “the Serjt of the Husaws then Struck the Serjt of the Gaurd with the Same Stick as he struck the Prisoner with & took hold of him struck & Dragg’d Him from the Gaurd hause door into the Street & would have had Kill him had not Capt. Cregg not Come timely to Prevent it.”[29] This just led to more trouble: “a Great mob of Husaws & Inhabitants assembled. Capt. Cregg being Present order them to Disperce but they would not but Still Resisted, he orderd the Gaurd to Fier then they Dispersed.” Word soon came that the dragoons under Pulaski were grabbing their arms and clubs “for to do some mischiefs to us.” About 20 men arrived and assaulted the Invalid guards, but the Invalids fought back, stabbing one of the dragoons with a bayonet (you just don’t mess with wounded veterans).

On the flip side of the argument, the officer in charge of the dragoons deposed that the prisoner they were returning was a deserter and that they enlisted the aid of the Invalids to track him down. The Invalids, “were all drunck, and to whom, as soon as they came, my Prisoner spoke a few Words in English, which my Men did not sufficiently understand, whereupon the Guard of the Invalids, took my Guard (who had no Arms) under Arrest.”[30] The Invalids eventually released the dragoon sergeant and were asked by thier officer to hold the deserter in jail. But as it supposedly happened, “the Prisoner (who had already received Clothing, Bounty, Shirt, Shoes &c.) had deserted from the Guard and that the Invalids had aided and assisted him in doing so.” He placed blame for the fight on the Invalids:

“Upon this I immediately sent out my Men to search for the Prisoner in our Quarters; but my Under-Officer was attacked in the open Street by the Invalids, who beat him with Sticks, and upon the Arrival of a Serjeant and a Dragoon, who came to make Peace, two of my Men were stabbed thro’ their Bellies, with Bajonets and one shot thro’ the Hat, and that by Order of the Serjeant of the Invalids. Both these Men are dangerously ill at present, and I don’t know if one of them will recover.”

30 residents of Easton wrote a letter in support of the dragoons, and against the Invalids, writing “That Some Invalides under the Command of Coll Nicholas; have Since behaved themselves very immodest, incivil and not like Soldiers, but Villainous & roguish.”[31]

Things quieted down after that, for the most part, but in 1779 over 500 prisoners from Stony Point were sent to Easton for incarceration.[32] Later, in June of 1781, between 250 and 300 prisoners were sent to Easton from Lancaster.[33] How many survived their imprisonment and how many perished is unknown, but given Easton’s history it would be unsurprising to find that some of them died.

Easton saw many casualties during the tenure of the war. Between sick and wounded Continentals and sick and wounded prisoners, one could easily give a conservative estimate that the total number of dead had reached 300, though it may have even surpassed this. Many of the deaths seem to have gone unreported, or the reports are now missing. But this seems to be true for all the hospital sites in Pennsylvania during the war; if not for the diaries at Bethlehem, it is likely we would not have known about the mass grave there. Happenstance alone has meant that certain hospitals are better attested to than others, which is unfortunate.

But the real tragedy here is that the neglect of the Easton hospital and prisoner of war dead has meant that their final resting place has not been discovered. Easton today is much more urbanized than it was during the war, with much of the construction happening during the Victorian Period into the first decade of the twentieth century—a period when people just didn’t care about disturbing grave sites, and those that were found went unreported to authorities. Somewhere in Easton lies a mass grave (or maybe more than one). This is not just a local matter. Soldiers from all over, even from across the ocean, gave up the ghost in this little town on the bank of the Delaware. That makes it, in my humble opinion, a national story. With a little bit of effort, those lost soldiers can be remembered.[34]

[FEATURED IMAGE AT TOP: Center Square Easton, PA, circa 1780. Courtesy of Northampton County Historical Society]

[1] Sometimes this rate was higher—especially at the hospital’s conception, prior to the small pox inoculations in 1777.

[2] Now that area is a residential neighborhood that went up in the Victorian period; human remains are occasionally uncovered by homeowners landscaping their front lawns, or when construction is done near the marker. Most recently, in 1995, a grave was uncovered when a retaining wall was being placed.

[3] Easton’s population, according to census records, is now over 27,000.

[4] Henry Dearborn, Revolutionary War Journals of Henry Dearborn, 1775-1783 (Chicago: The Caxton Club, 1939), 157. The area to which Dearborn refers still maintains a name suited to this appearance: Dryland. But Dearborn was wrong. Incidentally, it’s now one of the ritzier areas of the Lehigh Valley.

[5] ‘Sergeant John Smith’s Diary of 1776’, Louise Rau, ed., The Mississippi Valley Historical Review, Vol. 20, No. 2 (September 1933), 247-270.

[6] Sergeant John Smith’s Diary. Smith and some of his company helped themselves to some cider and food from their cellar that evening, about which the woman of the house complained for some time, and the next morning he set off with his company.

[7] William Shippen would write to Richard Henry Lee from Bethlehem, “I saw all his [Lee’s] troops, about four thousand, this morning, marching from Easton, about two days’ march from Washington, in good spirits, and much pleased with their General [Sullivan]. General Gates, with nine hundred men, marches from this place this afternoon and to-morrow. We hear General Heath is within four days’ march, with three thousand men.” http://lincoln.lib.niu.edu/cgi-bin/amarch/getdoc.pl?/var/lib/philologic/databases/amarch/.28186# , accessed 22 July 2014. These numbers were corroborated by the Moravians at Bethlehem; see John W. Jordan, et al, ‘Bethlehem during the Revolution,’ The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography, Vol. 12, No. 4 (January 1889), 394-395.

[8] Shippen writes, ““After much difficulty and expense, I have removed all the sick to Easton, Bethlehem, and Allentown; their number is now much reduced, and all in a good way. I send twenty or thirty weekly to join the Army.” Sergeant Smith also recalled about 500 British prisoners being sent to Easton to be exchanged.

[9] “The Number of sick & wounded in my department is 338 – 4 fifths of them are in a fair way of recovery & will soon join their respective companys. I have not yet taken charge of near 2000 that are scatter’d up & down the Country in cold barns & who suffer exceedingly for want of comfortable appartments, because Dr Morgan dont understand the meaning of the Honble Congress in their late resolve, & believes yet they are to be under his direction although they are on this side Hudsons River. He is now gone over to take General Washington’s opinion—As soon as I recieve the Generals Orders on the subject I shall exert my best abilities to make the miserable soldiery comfortable & happy.” William Shippen, Jr., to Washington, 29 October 1776; http://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-07-02-0039 accessed 22 July 2014.

[10] Jordan, ‘Bethlehem during the Revolution’, 393.

[11] R.L. Blanco, ‘American Army Hospitals in Pennsylvania During the Revolutionary War’, Pennsylvania History 48, no. 4 (1981), 352; Blanco estimates that about 500 were sheltered in the hospitals at Philadelphia over the winter of 1776-1777.

[12] William Shippen, Jr. to Washington, 8 December 1776; http://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-07-02-0219 accessed 18 July 2014.

[13] John Adams to Abigail Adams, 13 April 1777; http://founders.archives.gov/documents/Adams/04-02-02-0158 accessed 18 July 2014. He went on to give context: “The Graves of the soldiers, who have been buryed, in this Ground, from the Hospital and bettering House, during the Course of the last Summer, Fall, and Winter, dead of the small Pox, and Camp Diseases, are enough to make the Heart of stone to melt away.”

[14] One physician, Azor Betts, was caught inoculating soldiers while stationed in New York in 1776, just days after Washington gave the general order against inoculations. Betts had a history of being a disaffected person and a Tory and it is unclear whether he was acting in the best interest of the troops or the general population, but he was tried and thrown in jail. Betts asked forgiveness, stating that he “meant not to injure those gentlemen who were inoculated, nor to show any contempt to your worshipful House, but ardently wished to render his best services to those who had the command in relieving them from those fears which people in general have who are subject to that disorder.” Upon his release, he joined a Loyalist regiment, the Queens Rangers, as their surgeon. Nevertheless, Washington’s failure to allow for inoculations may have led to a broader epidemic. See General Orders, 26 May 1776: http://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-04-02-0312, accessed 23 July 2014.

[15] Jordan, ‘Bethlehem during the Revolution,’ 405.

[16] John W. Jordan, et al, ‘Bethlehem during the Revolution (Concluded),’ The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography, Vol. 13, No. 1 (April, 1889), 75.

[17] Jordan, ‘Bethlehem during the Revolution (Concluded),’ 76.

[18] Mary C. Gillett, The Army Medical Department, 1775-1818 (Washington: Center of Military History, United States Army, 1981), 80.

[19] Robert Levers wrote to President Wharton on 27 December 1777 asking about four brigades of wagons “ordered to be raided directly, to convey the sick passing thro’ this place [Easton] from Princetown.” Pennsylvania Archives Ser. 1, Vol. 6, 141.

[20] Pennsylvania Archives Ser. 1, Vol. 6, 106.

[21] Requested by Shippen, but approved by Washington: “As to Colo. Nichola & his Corps I shall have no Objection to their being at the Hospitals, if there is no Resolution of Congress assigning them to other duty.” George Washington to William Shippen, Jr., 12 December 1777: http://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-12-02-0548 accessed 23 July 2014. See also George Washington to Richard Peters, 14 December 1777: http://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-12-02-0554 accessed 23 July 2014.

[22] Pennsylvania Archives Ser. 1, Vol. 6, 198.

[23] Because of the shortage of men on the home front, given Pennsylvania’s new militia law, Robert Lettis Hooper, Jr., would send off the Hessian prisoners to work for the German farmers in the county while on parole—they even earned a dollar a day in some instances. Many remained in Pennsylvania after the war. The most famous is the Hessian prisoner-turned-citizen Isaac Clinkerfoos, who faced some heavy persecution even after many local citizens in Easton and neighboring Phillipsburg, New Jersey, vouched for him and his character. His depositions and those of his supporters and inquisitors can be found in Pennsylvania Archives Ser. 2, Vol. 1, 457-465. It is unclear why the Hessians were given favor over the British POWs, but it may have something to do with the high population of German immigrants in Easton.

[24] Benjamin Rush to Washington, 25 February 1778: http://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-13-02-0564 accessed 23 July 2014.

[25] Note 7 to transcription of Rush to Washington, 25 Feb 1778.

[26] See full report with additional details, Brigadier General Lachlan McIntosh to Washington, 26 April 1778: http://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-14-02-0580 accessed 23 July 2014.

[27] Confirmed by other reports as well; this was decided by Shippen and Washington back in December. Washington wrote, “In answer to your Favor of to day, I cannot think Princeton under the present situation of affairs by any means a proper place for the sick. Should they remain there they would be liable to be taken. At the same time, I do not wish you to precipitate their removal in such a manner as to endanger them. In respect to the Hospitals at Easton & Bethelem, I also am of Opinion, that they should be removed. But these, as their situation is not so dangerous, may be deferred till the last.” George Washington to William Shippen, Jr., 12 December 1777.

[28] Transcribed from a facsimile copy of the original manuscript, sent to me by the Northampton County Historical and Genealogical Society; a complete transcription (along with transcriptions of other letters by Hooper about prisoners in Easton) can be found in The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography, Vol. 40 (1916), 497-498.

[29] The author of this deposition, Captain John David Woelpper, was originally an officer in the German Battalion—his grasp of English was clearly better than some, but not as clear as others. Still decipherable, though. For the full deposition, see: Captain John David Woelpper to Washington, 22 June 1778: http://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-15-02-0527 accessed 23 July 2014.

[30] Colonel Michael de Kowats to Washington, 26 June 1778: http://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-15-02-0584 accessed 23 July 2014.

[31] Note 2 to transcription of de Kowats to Washington, 26 June 1778. Apparently the Invalids were known to commit all sorts of criminal acts, like “breaking open the Storehouses and as the greatest Thiefes Stealing the Peoples Money & other Sundry Goods more out their Houses and breaking Several Locks of Store & Houses here.”

[32] Henry Phelps Johnston, The Storming of Stony Point on the Hudson, Midnight, July 15, 1779: Its Importance in the Light of Unpublished Documents (New York: James T. White & Co, 1900), 207. According to the figures, which are also found in the George Washington Papers, Series 4, General Correspondence, 441 privates and 25 officers made it to Easton. Two officers were killed and 43 enlisted were wounded in an escape attempt along the way. Only 9 of those wounded were left where the escape attempt happened, as they were too badly injured to be transported, along with two caregivers. It seems reasonable to assume that some of these wounded soldiers died while in prison at Easton.

[33] Pennsylvania Archives Ser. 1, Vol. 9, 224-226. Apparently Lancaster was without arms and with no means to guard the 1700 prisoners of war stationed there; they had to send some of them to Easton—but they didn’t have enough guards to make the trip without them being overpowered. So they sent for militia at Easton to help escort them. It is unclear how many of the prisoners were escorted, but Colonel Adam Hubley requested at least 250 armed guards to watch them. It could have been a significantly higher amount than the number listed above.

[34] I am currently working with several people, including the current mayor of Easton, Sal Panto, to raise a memorial to those who died at Easton during the war.

30 Comments

So I just noticed I used the wrong version of ‘capital’ (I referred to Easton as a ‘capitol’–whoops!). Besides my own re-readings, it went through two editors and several revisions and was missed every time. It happens. Please read sympathetically, if you’re feeling generous!

Corrected.

You (pl.) rock.

Thank you, Thomas! You see things once they are “in print,” even on a webzine. I just said that the imaginary Robert Hulclip had cheated the “Haselip’s” out of the glory of having a signer of the Tryon “Association” in the family A simple plural would have done . . . .

Awesome article!

Thanks! Glad you enjoyed it.

Excellent article.

Thanks Scott!

I always wondered where the diseased, sick, invalid and wounded soldiers went and what happened to them. This also includes where did all of the POWs – both sides – ever go? What became of them? We read about the battles and skirmishes and the resultant casualties then everything drops off. Thanks for a good piece of insight on a very interesting topic. Also, the sanitary conditions at the hospitals must have been horrible. I can understand why people were reluctant to expose themselves to disease and filth when so many sick and dirty men were concentrated in a such a small area. How did the Revolutionary Army handle basic everyday sanitary needs when settling down in towns such as Easton, or while on the march through other towns and communities? How about when confined to hospital? Surely their habits back then contributed mightily to their sick and suffering ways.

Thanks again for sharing such informative detail on a topic rarely discussed in any depth.

John Pearson

Thanks! One thing I did not have the space to touch on was that as a result of the extremely high death toll in hospitals and in camp due to disease, Washington ordered strict sanitary measures to be taken by all veterans and new recruits. Shaving consistently, washing, etc… though obviously antiseptics had not yet been invented; these procedures did actually help a great deal.

Another interesting bit of information is that at Valley Forge, they kept the latrines next to the commissary and food stores. It took them a while before they realized that part of the reason why so many men were dying and had contracted dysentery was due to this (now obvious) placement. It’s estimated that 1/4 of the army perished there from these diseases, as well as starvation and exposure (incidentally, no one knows where these men are buried). When Washington set up camp at Morristown in 1779-1780, his men had learned from their mistakes at Valley Forge which saved the lives of countless hundreds from the same fate.

So there is a bit of trial and error involved.

Thanks for reading!

I would like to read the entire article especially anything on Easton that you have written and review it for the Sept. issue of the Easton Irregular ‘zine. Kindly let me know how I can see and read the article on line.

Certainly. All of my articles may be relevant to you (with the exception of the piece I did on Sleepy Hollow):

https://allthingsliberty.com/author/thomas-verenna/

Follow that link and you will find all my work.

You can contact me at: th************@ru*****.edu

Thanks for the interesting article. I just saw an announcement of a new book about the prison in Lancaster, PA and what its impact was on the local population. Have you read anything about it? “Dangerous Guests: Enemy Captives and Revolutionary Communities during the War for Independence” by Ken Miller.

Watch for a review of “Dangerous Guests” that will be posted here in the coming weeks!

Nice!

I haven’t read anything about it; though I certainly look forward to reading it. Lancaster was as volatile an area as Easton during the war.

What a fascinating subject! I am still wondering how all of the desperately sick Revolutionary War soldiers – both sides – were ever able to travel for such long distances – such as Morristown, NJ to Easton or Bethlehem/Allentown PA 50-70miles and even longer treks such as Montreal down to Fort Ticonderoga and beyond. I constantly read of numerous terribly ill soldiers traveling long distances to other locations. Many of them were small pox victims and yet traveled! By horse and cart, boat and walking, in terrible weather year round. The suffering was incalculable. I still have trouble envisioning all of this – yet considering what`s happened these last 2 centuries (Civil War – WW1 & WW11 and current affairs) may be it`s somewhat easier to understand it if at all.

Thanks,

John Pearson

John,

Good question! In 1776, we see most men being carried into town by friends and fellow soldiers. But in the harsh weather, they were nearly naked and filthy (to which many respectable townspeople complained). However by 1777, the establishment of a new government in Pennsylvania meant that many wagons could be commandeered for transporting the severely sick and wounded. That didn’t seem to stop some from making the journey by foot; it raises another question: how many soldiers died on the long road to the hospital? Where are THEY buried? How many road-side graves are lost? I wonder if we will ever know.

Hi Again,

I met to say that I had no idea of the sanitary situation at Valley Forge! What possibly could these people in the Army have been thinking?! Wake up! After all the Roman Empire 1,500 – 2,000 years before knew all about the importance and details involving sanitary living. This horrible situation probably happened elsewhere in the War. What about in the Cities such as Philadelphia and New York during the war? Did those people conduct their sanitary affairs the same way ie. Outhouse in the Kitchen? or vice versa. I know I have gotten off course here but I have learned something new about the Hospitals and Valley Forge. I am chagrined that so many good people perished due to lack of common sense and probably gross negligence!

Thanks.

John Pearson

Officers and aspiring military men of the 18th century could draw on a rich literature of military textbooks (in English, French and German) that gave detailed guidance on many things including hygiene and sanitation. Among military professionals it was well known that simple things like careful placement of “necessary houses” and proper disposal of food and butchering waste went a long way towards preserving the health of armies. Books of this sort were available in America before and during the war, and many American officers had prior military experience – not to mention a couple of years of experience during the Revolution prior to Valley Forge. How a fundamental mistake of sanitation could have been made is indeed a puzzle, for these were not foolish men learning haphazardly by trial and error – Valley Forge was a well-laid-out military cantonment.

Sounds like something that requires further research to fully understand.

I wonder if the haste ( am I assuming this is right ) in setting up the initial encampment at Valley Forge had anything to do with the poor choice of sanitary and commissary locations. The army had just fought a good size battle at Whitemarsh in early December and needed to get away in order to quickly set up shop for the winter.

John Pearson

Yes, but Valley Forge was strategically chosen by Washington as well; it was far enough away from Philadelphia where a surprise attack would be difficult to pull off (it had a commanding place of the region), but was close enough for Washington to keep an eye on Philadelphia should the British pull out. Also, while completely unreliable, undersupplied, and frequently understrength, the Pennsylvania militia was tasked with patrolling the local counties and that freed up Washington to focus on his Continentals. I think a basic lack of experience played a role; Washington often left the day to day tasks of the army in the hands of subordinates and it is unclear if that played a role in the initial sanitary problems (with a lack of any general orders) or if the commissary was established by outside parties (like local merchants/vendors). Either way, I think Don is right that this is something that should merit further study.

Thanks Thomas,

It still is amazing to me that this type of thing happened, especially when Washington wished to preserve a high degree of manpower for the upcoming campaigns. Can he share some measure of responsibility and accountability even though today it seems politically incorrect to criticize the 1st Commander in Chief. Was he unaware of the sanitary problem because he lived fairly well in a mansion somewhat removed from the huts? Presumably not since his officers kept him closely apprised of all affairs. He was fastidious about his personal guard and his own cleanliness and appearance. The enormous sickness fatalities surely would have concerned him, I believe, and after discovering the problem I would think he would have felt awful and held those responsible accountable. May be not!

Any more thoughts on the real reasons behind the tragic death rate at Valley Forge.

Thanks again.

John Pearson

I’m fairly certain that I do not know whether or not Washington shares some of the blame. Certainly he was being lied to (as demonstrated above in the article), and his top surgeons were concealing the actual number of casualties from him, but at Valley Forge it would have been hard to do. Unlike at Morristown where Washington was living in an estate in town some few miles away from Jockey Hollow, at Valley Forge he was housed adjacent to the camp.

Nevertheless, it is possible that he was so wrapped in other responsibilities, he could have not realized just how terrible the suffering had been. Also the camps, while highly organized, were also a bit lacking in uniformity. Some troops wanted for more while others were better off than most. And if officers were under-reporting things, and if his subordinates were dealing with the sick, maybe he wasn’t as aware of the problem as he should have been. But I really can’t say with any level of certainty until I look into it, and right now I just don’t have the time.

So I uncovered this newspaper article from 1780; the published disposition of a soldier overseeing some of the Continental Hospitals in Pennsylvania. He writes mainly about the hospital at Reading, but given what we know about them, this seems to ring true about all of them:

http://historyandancestry.wordpress.com/2014/10/01/just-how-bad-were-the-conditions-in-continental-hospitals/

Mr. Verenna

I am a local historian and really enjoyed your “Easton’s Missing Dead.”

I schedule a First Monday Program at Easton Area Community Center and wonder if you could give a talk on this subject. The presentations begin at 12 noon and are free to the public. I am setting up presentations for 2015. The dates available are Oct. 5, Nov. 2, & Dec 7.

I understand that is some time off but I would really like to hear your talk. Leonard Buscemi

Leonard,

I sent you an email to make arrangements. Thank you again for your very generous offer!

Tom

Thanks, Thomas, for your wonderful research on this matter! While tracing some of my own family during this time period I stumbled upon an article referring to an Easton company of militia- that the following persons be detained from marching with the said company, to the camp, viz: Robert Traill, & Treasurer to this Committee, Henry Strouse (my relative), Joiner, employed in making coffins for such of the soldiers as shall die in Easton, Henry Shnyder, & Nicholas Traxel, shoemakers, Abraham Berlin, Junr., gunsmith, Jacob Berlin, blacksmith, and Peter Ealer, keeper of the Goal of this County.

Thank you for your informative articles. I came across a comprehensive history of Lehigh County, PA published in 1902 by James J. Hauser. It mentions the burial of the Revolutionary War soldiers:

“On a hill on this side of the Monocacy Creek and on the right side of the

road, leading to Allentown, now occupied by West Bethlehem, lie buried about one thousand Revolutionary soldiers, who died while the military hospital was located at Bethlehem. A monument should mark their last resting place.”

It also mentions many subsequent floods of the Lehigh River.

If my link doesn’t work, Google, “ History of Lehigh County, Pennsylvania.” The documents are archived in the Library of Congress.”

https://tile.loc.gov/storage-services/public/gdcmassbookdig/historyoflehighc00hauser/historyoflehighc00hauser.pdf