The evacuation of Fort Ticonderoga in July, 1777, is a well-known incident of the American Revolution. Directly related to it is the Battle of Hubbardton, the only Revolutionary War battle fought in Vermont.[1] Often, sources of information found on one incident will add to the knowledge of the other and such is the case with a letter written by Lieutenant Colonel George Reid, second-in-command the 1st New Hampshire Regiment and also of the rear guard during the evacuation. On 22 July, just over two weeks after the evacuation and battle, he wrote to his brother telling him about the events. The letter does not significantly alter what is currently presented as the story of either event but, rather, expands on the interpretation by adding new information. The following is an overview of the events followed by some relevant details contained in Reid’s letter.[2]

The Situation

In the early summer of 1777, General John Burgoyne led a British army of 8,000 out of Canada up Lake Champlain with Albany, New York, as their objective. They knew their first resistance would be at the works being repaired and expanded at Ticonderoga and the new fortifications across “the river” at Mount Independence.[3] A quarter-mile long floating bridge connected the two posts.

The Americans had a problem, however: they had fewer than 4,000 soldiers to man positions that normally would require 14,000. Lacking adequate numbers, the Americans contracted their lines in the face of the advancing British. By 5 July, Burgoyne’s army had taken most of the outer works around Ticonderoga, threatened to cut off the overland retreat route southeast of the Mount, and had begun construction of an artillery battery on high ground overlooking both positions. Under these circumstances, the American commanders decided to abandon the posts. Some troops would move by water to Skenesborough (now Whitehall, New York) carrying the sickest men and what supplies and baggage they could. The majority of the army would march overland to Castleton, Vermont, and then turn west to rejoin the waterborne body.

The Retreat and the Pursuit

On the evening of 5 July, Colonel Ebenezer Francis received orders to reinforce the 150-man picket—the guards stationed outside the normal defensive positions—with 310 of the best men in the American units.[4] While they watched for deserters and any attack, the rest of the army broke camp and began to abandon the positions under cover of the darkness of a new moon. Once the main body had crossed the bridge, Francis’s picket left their post and began the retreat, serving as the army’s rear guard.

About the same time as the picket left the Mount, the British discovered the American move and Brigadier General Simon Fraser with his advance guard of two companies of the 24th Regiment, ten companies each of light infantry (agile, lighter-equipped men used for quick movement) and grenadiers (bigger men used as shock troops), and a few loyalists (Americans who sided with the King and Parliament) and Indians—about 850 men—set off in pursuit.[5] Burgoyne ordered a large body of Germans to follow after Fraser as soon as possible.

Both armies pushed hard over the course of the sweltering 6 July with the majority of the Americans marching thirty miles to Castleton. Seth Warner’s Green Mountain Boys and Nathan Hale’s New Hampshire regiment waited where the road from Mount Independence joined the Castleton Road at Hubbardton seven miles north (this Nathan Hale is not the same one executed as a spy). Once Francis arrived with the rear guard, Warner had orders to take overall command of the combined forces and move to Castleton.

But, by the time the rear guard arrived, they had gathered up scores of sick, lame, and lazy men too exhausted to move on so Warner decided to spend the night at Hubbardton. Some of Hale’s men and most of the stragglers swept up by Francis’s rear guard settled down along the military road near a stream known as Sucker Brook. Warner’s, most of the rear guard, and the rest of Hale’s regiment camped just north of the junction on the top of a steep hill that rose 150 feet above the military road. In total, the Americans may have had over 1200 men resting at Hubbardton.[6]

Fraser’s advance guard also needed to rest and stopped at a place called Lacey’s Camp three miles west of the Americans. They arose before 4:00 a.m. on the 7th and resumed their pursuit. Fraser sent his loyalists and Indians ahead to scout for the enemy and soon received word that the Americans had many more men at Hubbardton than just the rear guard. He sent word back for the Germans to come on as quickly as possible while the advance guard continued their pursuit.

At Hubbardton, Warner deployed pickets to watch for the approach of the British. On the morning of the 7th, while awaiting the return of a scouting party, the Americans ate breakfast and prepared to continue the march to Castleton. The regiments on the hill began forming but the Americans spread out near Sucker Brook had problems. Large numbers of individuals picked up by Francis’s rear guard had no officers on which to rely for orders and they made for considerable confusion and delay in trying to get the entire group moving. Nobody knew how close the British actually were.

The Battle

As Fraser moved closer to Sucker Brook in the early morning light, the men leading the column received scattered fire from the American pickets who quickly fell back. The battle had begun. Following hard on the heels of the retreating pickets, the British came upon the camp and attacked around 7:00. In their surprise, some Americans fled into the woods but individuals and groups put up what resistance they could.[7] In spite of the occasionally stiff resistance, Fraser’s men overran the disorganized resistance and continued driving on.

As the British column began to form for battle, Fraser ordered the men of the 24th Regiment to “take post” (meaning the right flank) and intended to form the light infantry to the left while keeping the grenadiers as a reserve. Once across Sucker Brook, however, the situation caused a change in plans. The column found themselves at the base of the western side of the hill so Fraser faced his light infantry to the left into line of battle and advanced up the steep incline while the 24th moved towards the road junction.[8]

Being better rested and part of cohesive units, most of the Americans camped on the east side of the hill and near the intersection of the roads had already formed a column headed south when the British arrived at Sucker Brook. With the men near Sucker Brook already in a fight, the Americans could not move away so they headed for the crest of the hill—the same crest Fraser’s light infantry had begun to climb on the opposite side. The two forces met at the crest and, by 7:20, had begun to exchange heavy fire.[9] While Francis’s men in the American center and Hale’s on the right held steady, Warner’s regiment began to drive the 24th back which threatened to collapse the British right. Fraser saw the danger and ordered the grenadiers to support the 24th and attempt to cut off any American move down the Castleton road. Fraser now had committed his entire force. If things went badly, he had no reinforcements.

For several minutes, the battle moved back and forth on the hill. Eventually, the grenadiers gained the left flank of the Americans and forced them to slowly withdraw to a “hill of less eminence” east of the crest and then behind a fence on the east side of the Castleton road.[10] Emboldened by the added protection, American resistance became quite stiff and drove the British back. Fraser attempted another attack but the Americans repelled that one as well.[11] On the American right, the New Hampshire men saw a weakness in the British line and moved to the attack forcing the British light infantry on that flank to begin to withdraw under the pressure. The situation Fraser had risked by committing the grenadiers had developed.

The Americans did not know, however, of Fraser’s back-up plan. At just the moment of greatest peril to Fraser’s left, the advance companies of the German reinforcements arrived. A force of 125 jaegers (a type of light infantry), with music playing and reportedly singing, attacked the American right while another party of about the same number attempted to move to the rear of the Americans.[12] This unexpected assault caused the American line to collapse, but the men had little choice as to the route of escape. The British grenadiers had gained the top of Pittsford Ridge behind the American left and the German grenadiers threatened to do the same on the right. Nearly surrounded, the Americans now ran to get away over the part of the ridge remaining open.

It had been a long battle. The action at Sucker Brook had begun around 7:00 and the American line broke around 8:45. Scattered encounters on Pittsford Ridge continued for another hour. After the firing had ceased, some British officers gathered around the body of Colonel Francis, the commander of the American rear guard, who had been killed. As they read the papers Francis had in his pocket, a lone American fired from cover and killed one of the group of officers. This might well have been the last shot fired in an action that cost the Americans 41 killed (including Francis) and 96 wounded—about 12% of their men. But, they also lost around 240 prisoners (including Hale who would die in prison in 1780), mostly taken during the Sucker Brook phase. The British and Germans had 60 killed and 150 wounded. Fraser’s advance guard suffered 22% casualties and had taken enough of a beating that they did not continue the pursuit.[13] The bulk of the American army had escaped.

The Letter’s Bearing

Lieutenant Colonel Reid’s letter offers both new information and support for findings from recent research. For example, most people believe all the Americans left Ticonderoga and Mount Independence under the cover of darkness. While they certainly began preparations in the dark, recent work[14] has found evidence that they actually did not leave until after day break and Reid supports that conclusion: “We marched the Picket to its station there stood under arms till day break or a little after.”[15] What did Reid mean by “daybreak?” In early July at Ticonderoga with its low eastern horizon, sunrise would have been around 4:15. Twilight is over two hours long at that time of year so the sky would have been noticeably lighter by 2:30 a.m. Whatever the time, it is clear the rear guard did not leave in the dark.

Reid goes on to write that they “were detained some time on the Mount to cut the bridge.” The usual story of the retreat fails to mention that the Americans did anything to the bridge but Reid claims the rear guard inflicted some damage. Indeed, General Fraser in a letter to a friend in England commented that the Americans departed, “destroying nothing but the Bridge of communications between Ticonderoga & Mount Independence, I got planks, by means of which I cross’d my Brigade to the Mount.”[16] Regrettably, exactly what damage the rear guard did remains unknown.

Many historians have written that the Americans left a cannon crew to fire on the British as they crossed the bridge, but they got drunk, passed out, and became prisoners. This is based on one questionable British reminiscence.[17] Reid writes in his letter that the British, “fired upon some of our artillery men before we left the Mount and kill’d one.” Clearly, some artillery men remained after the main body had gone but did they leave with the rear guard? It seems a bit odd that Reid—or any other source—failed to mention men staying behind to delay the British. And, it also seems a bit odd that the traditional story says nothing of the crew being fired upon let alone one being killed. Reid’s comments seem to lessen the validity of the story.

Reid mentions two incidents that this writer has never heard before. In the first, he notes that, “we march’d on after the main body about 12 or 14 miles when 3 or 4 Indians attack’d 3 officers with their baggage horse. They took the horse but the officers escap’d.” For the second, when talking about the decision to spend the night at Hubbardton, he writes, “we took three prisoners in the evening.” On the face of them, the stories are merely interesting vignettes (the first interesting to us—terrifying to the officers), but the second is the only report of the Americans taking prisoners during either the retreat or the battle. Both hint at just how closely the British followed the retreating Americans.

As is common with uncovering new information, new questions arise. Reid writes that, “as soon as the alarm came [notice of the British approach] I formed our Regt on the left.” But, which regiment? His own New Hampshire regiment? Or, the rear guard he temporarily served with? Since Reid’s other references to his temporary assignment call that body the “picket” or “rear guard,” it is safe to assume later mentions of his “regiment” refer to the New Hampshire unit. Historians have assumed that Francis’s own Massachusetts regiment made up the greater portion of the rear guard and fail to give much, if any, credit to any other regiments except Warner’s and Hale’s. In actuality, recent research has found that elements of several regiments took part in the battle including at least three companies from Reid’s New Hampshire regiment.[18]

With the Americans camping in two locations, the battle consisted of two different phases. Which one did Reid take part in? We cannot be positive but he does give some hints in his description:

in the Morning when our troops were about to Muster in order to march, an alarm came in that a large body of the enemy were close upon us, what part of our Regiment were with me happened to be just drawn up and marching towards the left which was our way to proceed, as soon as the alarm came I formed our Regt on the left, but the whole having but little time was in Considerable Confusion, it was not over ten minutes from the time we had the first notice untill we received a verry heavy fire from the enemy, though we were taken at much advantage being in the open field & our enemy in the woods in short shott, we stood in the field and behind stumps to the value of 20 minutes or halfe an hour after which we were obliged by superior force to fall back into the wood and then we fought them on the retreat about a mile & halfe upon which we found we were flank’d on all quarters by a great number of Indians, I had betwixt fifty & sixty that stay’d by me that I brought in to the main body about the middle afternoon,

The description could mean Reid’s men gathered on either road but further comments indicate they formed on the military road below the hill. For example, he says he formed his regiment on the left but all other evidence puts Warner’s men on the left of the line on top of the hill. For another example, he comments on the “Considerable Confusion” of the majority of the troops. Most of the men on the hill had formed when the battle came to them. Reid goes on to comment about his men “being in the open field & our enemy in the woods in short shott.” Such an arrangement on top of the hill would have Reid’s men some distance down the Castleton Road at least where Warner’s formed. In addition, the timing is wrong for the action on the hill. Reid and his men fought, at most, a half hour before starting to fall back into the woods. Based on other sources, that is about the time the first phase of the battle lasted. The action on the hill moved back and forth and lasted at least an hour before the Americans retreated over Pittsford Ridge. These factors alone would be enough to place Reid and his men at Sucker Brook.

For the doubting reader, Reid’s letter includes other, more convincing, evidence. He writes how “we fought them on the retreat about a mile & halfe upon which we found we were flank’d on all quarters by a great number of Indians.” Fighting on the retreat certainly could refer to the action on Pittsford Ridge but there are no sources that mention Indians in the fight on the hill or on the retreat over the ridge. However, Fraser had sent a party of Indians and loyalists to scout to his right so, with no evidence of Indians in the main battle, Reid and his men likely fought this group while they tried to retreat towards Castleton. And, the last piece of evidence concerns another bit of timing. Reid made it back to the main body by mid-afternoon. If he had retreated over the ridge after the main battle, there is no way he could have been in Castleton that soon.

Reid’s letter even includes a bit for those interested in clothing. He notes that he had “no coat on but a linen rifle one.” Rather than the regimental coat with tails typical for an officer of the period, this is likely a simpler lighter-weight garment without tails and possibly with a cape and fringe. It is also possible that another officer wore a similar garment. When Reid arrived in Castleton, others from his group who had arrived earlier “asserted that I was shott through the body & they saw me fall.” Reid would have been easily recognizable to the men in his own regiment and probably to those in the rear guard. How did they confuse him with someone else? Did they see at some distance another officer dressed in a similar manner fall? Yet another example of more questions being created when finding some answers.

The above interpretations of Reid’s comments certainly are not final. They are but ones this author has proposed based on his knowledge of the events and the sites. However, more work needs to be done to support or contradict the interpretations. Those who took part in the events of those few days deserve it.

[1] The Battle of Bennington took place six miles west of the Bennington storehouse in New York.

[2] For a more detailed study of the retreat and the battle, refer to John Williams’ work, The Battle of Hubbardton: The American Rebels Stem the Tide (Montpelier, VT: Vermont Division for Historic Preservation, 1988).

[3] Lake Champlain ends at Crown Point. Many in the 18th century referred to the waters south of there as “the river.”

[4] Proceedings of a General Court Martial, Held at White Plains, in the State of New-York, by Order of His Excellency General Washington, Commander in Chief of the Army of the United States of America, for the Trial of Major General St. Clair, August 25, 1778 (Philadelphia: Hall and Sellers, 1778), 26.

[5] John Burgoyne, A State of the Expedition from Canada (London: J. Almon, 1780), xvii. A typical regiment consisted of approximately 500 men divided into ten companies. In a British regiment, one company was light infantry and one was grenadiers. While a full-strength company could consist of around fifty men, the exact size of the companies in Fraser’s force is unknown. Unfilled positions, illness, and men left behind at Mount Independence and Ticonderoga certainly diminished the numbers considerably.

[6] Carmine Pacca, “July Guns and Colonial Patriots: The Battle of Hubbardton Revisited,” Rutland Historical Society Quarterly (Rutland, Vermont: Rutland Historical Society, 2005) 35 (1), 4-5.

[7] Ebenezer Fletcher, Narrative of the Captivity and Sufferings of Ebenezer Fletcher of New Ipswich (New Ipswich, NH: Ebenzer Fletcher, 1813).

[8] Simon Fraser to John Robinson, Skeensborough [sic], 13 July 1777. Printed in Proceedings of the Vermont Historical Society, October 18 and November 2, 1898 (Burlington, VT, 1899), 145.

[9] Moses Greenleaf, “’Breakfast on Chocolate:’ The Diary of Moses Greenleaf, 1777,” ed. Donald Wickman. The Bulletin of the Fort Ticoderoga Museum 15 (1997): 497.

[10] Fraser to Robinson, Proceedings of the Vermont Historical Society, October 18 and November 2, 1898, 146.

[11] Joseph Bird, quoted in Henry Hall, “Battle of Hubbardton,” (Barre, VT: Vermont Historical Society, n.d.), 19-20.

[12] Major General Friederich Riedesel, Memoirs and Letters and Journals of Major General Riedesel During His Residence in America, trans. William L. Stone (New York: J. Munsell, 1868), 1:115.

[13] Williams, The Battle of Hubbardton, 65.

[14] In particular, see Kathleen Kenny and John Crock, Hubbardton Battlefield State Historic Site (VT-RU-40): Historical Survey, Property Survey, and ABPP Documentation Project (GA-2255-08-028) Hubbardton, Rutland County, Vermont. (Burlington, VT; Consulting Archaeology Program, University of Vermont, 2010).

[15] George Reid to Jn. Neysmith, Moses Creek, NY, 22 July 1777. Printed in “The Mount Independence Courier,” Spring, 2011 (vol. 18, no. 1), 4-5. The “Courier” with the complete letter is available at http://035a6a2.netsolhost.com/wordpress1/historical-articles/reid-letter/.

[16] Fraser to Robinson, Proceedings of the Vermont Historical Society, October 18 and November 2, 1898, 144.

[17] Thomas Anburey, Travels through the Interior Parts of America in a Series of Letters by an Officer (London: William Lane, 1789; reprinted New York: Arno Press, 1969), 1:323-7.

[18] For the Hubbardton Battlefield Survey, Kate Kenney found evidence of large numbers of men belonging to certain companies from several regiments being in the battle (Kenney and Crock, Historical Survey, 27-37). Continuing research by this author has found more support for those findings.

16 Comments

Thank you, Mike, very informative!

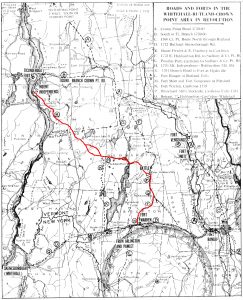

Glad you got something out of the article, Bob. It’s a complicated battle and Reid’s letter adds some new elements, particularly to the early phase. Gerlach’s map has its problems–some angles and distances to not jibe with reality–but still is a great aid in helping comprehend movements. One should visit the site to really gain a better understanding (I seem to remember talking with you there). It’s a small, out of the way but physically beautiful site and the docent (Karl Fuller) is as enthusiastic a guide as you will ever find.

Good article but isn’t the Battle of Lake Champlain considered to have happened in Vermont or was it on the New York side?

I’m not sure what you are referring to as the Battle of Lake Champlain. Hubbardton is about 10 miles as the crow barks from Lake Champlain into Vermont–over twenty miles by road from Mt. Independence.

Usually, the Battle of Lake Champlain refers to the battle fought at Plattsburgh, NY, in Sept., 1814, but, some folks use that name when referring to the Oct., 1776, Battle of Valcour Island. That action had three phases with the largest part of the battle taking place in the straits between Valcour Island and the New York shore. The second phase involved a chase along the New York side of the lake and the final phase had five of the American ships running aground and being burned by the crews in Arnold’s Bay in Panton, VT. The remaining four ships made it to Ticonderoga.

Very well thought out piece, Mike! The Reid letter is fascinating, and opens the door to new interpretation of the action at Hubbardton. I like your version, but it occurs to me there is another one that might fit the facts at least as well. What if Reid was initially deployed to the West/Southwest of the Selleck cabin? Based upon the Gerlach map, this would place him in a cleared but uncultivated area near the military road, and on the “left” of the American defenses, as Reid recounts. The initial 30 minute phase of the action would place him in an open area with dense woods to his west and south. Reid’s reference to the highly disorganized portion of the army would place the stragglers in the vicinity of Selleck’s cabin, which I recall is where the archaeological report you cite suggests they were. As for the timing of the rest of the action, the flanking maneuver of the Grenadiers could have forced Reid’s withdrawal to the woods in a southerly direction; if the action took place over a mile and a half in dense woods, as Reid describes, that would have certainly taken some time while the battle to the north was raging and would have delayed the advance of the Grenadiers. Moreover, Reid’s reference to Indians is consistent with other accounts placing Indians in the vicinity of Mount Zion, and I agree with you that it appears that Reid retreated directly south to Castleton and not over Pittsford Ridge.

Hello, Lieutenant Barbieri. My name is Susan Whitcomb. I am part of an extremely large Whitcomb Family in Long Island, NY. My husband and I, and many family members are extremely interested in our family history, and really loved the Living History story you authored about Benjamin Whitcomb’s Independent Corps of Rangers. Can you tell me if Whitcomb’s Rangers are still in existence? Do the reenactments still take place? Can people still join? I really appreciate and look forward to your reply.

Greetings Susan,

Indeed, the re-created Whitcomb’s Rangers still exists although our website disappeared and is under revision. Of course, we still participate in reenactments and will be setting our schedule for the coming season shortly. The unit does take on new members but requires that folks attend a couple events with us before joining. If you are just interested in history and unit news, we can just add you to our e-mail list. What’s your pleasure?

I meant to ask about the re-created Whitcomb’s Rangers. Is this organization still in existence?

Susan,

It has been quite some time since our original exchange but, if still interested, there now is a facebook page for Benjamin Whticomb’s Independent Corps of Rangers.

Michael,

I am in search for some information on John Selleck Esq. I was wondering if he was a loyalist or a Patriot.

Thank you!

Greetings Tami,

As far as I know (which isn’t too far in this matter) John Selleck and his family moved to Lanesborough, MA (in the northwestern part of the state near Pittsfield), after the battle and returned to Hubbardton following the war. He, his wife, and a couple of their children (if I remember rightly (it’s been a while since I visited the cemetery) are buried in a nearby cemetery. All that would make me guess he supported the American cause. It is my understanding that one of the sons moved to Canada so he might have had Crown leanings.

Hope this helps a bit.

Thank you Mike. He is my 6-X Great Grandfather and I am trying to get some information to verify my application to the Daughters of the American Revolution. I will do some research in MA.

Thank you again for your information.

-Tami

John was born (Norwalk maybe?) and lived in Conn. before moving to Hubbardton so you’ll find more early material there. I have no idea why they moved to Mass. for the duration of the war. I took a quick look at the Vermont Rev War Rolls and the service index for the National Archives collection of rolls but didn’t see his name. I think he was in his 40s at the time of the battle so may not have served in the military.

Hi – I read your excellent article as part of my search for background information about my 3rd great grandfather Ephraim Taylor who served as a private after he enlisted on January 1, 1777 in the Massachusetts company commanded by Captain George White in the regiment of Ebenezer Francis. Taylor wrote that he was captured by Indians during the Battle of Hubbardton and taken to Fort T and thence to Montreal and Halifax as a POW. He later escaped and made his way to Boston and served out his 3-year term in the hospital and than at West Point. He wrote his story in his 1835 Land Bounty Application. The story leaves me with many questions. I wonder if you could point me to some resources where I can learn about American prisoners in Montreal/Halifax and about prisoners captured at Hubbardton. Thank you! Dianne

John Selleck Jr., son of John Selleck, was born in Middlesex Parish in Stamford, CT (today’s Darien) in 1730. In the 1760s Selleck, Jr. and his wife Sarah Weed moved to Wilton Parish. In 1775 (as their son Dayle wrote in his claim to the Crown, “after the Troubles began”) Selleck moved the family from Connecticut to Hubbardton. All of this large branch of Stamford Sellecks were quiet loyalists and it is likely John, Jr. was also. Dayle served in the British provincial forces.

John, Sr., returned to Hubbardton in ’84 and the family remained there well into the 19th-century. Several of them are buried in the nearby Frog Hollow cemetery.