One of the great literary mysteries of colonial American history is the identity of “An American,” the anonymous author of American Husbandry (London, 1775). This writer dared to publish a plea to an unsympathetic British public not to allow the wealth and potential for the thirteen American colonies to slip away. A critic in 1776 denounced these two volumes as sedition by a Brit sympathetic to the cause of the ungrateful American malcontents.

Beyond its implications for the history of the American Revolution, American Husbandry is also a unique and extensive source on the agriculture and economics of Britain’s New World possessions. The Internet today lists hundreds of books and articles that, over two centuries, have used this work. Historian Harry J. Carman wrote, “of all our colonial literature, American Husbandry is the most accurate and comprehensive account of the English colonies and gives by far the best description of their agricultural practices.”[1]

How could anyone qualified to write such an encyclopedic work remain unknown? It could only have come from the pen of one of very few British agricultural experts of the Eighteenth Century but the identity of the book’s creator has remained a mystery since 1776.

The only review of American Husbandry published in its own time, by an anonymous reviewer, suggested that European pioneer agronomist Arthur Young (1741-1820) was “An American.” This was assumed only because almost no one else had the knowledge to write American Husbandry. Young hardly studied American agriculture until after the Revolution, however, as shown in his correspondence with George Washington. American Husbandry also contains glaring errors about sugar production taken from a Young work published years earlier, mistakes he surely would have known to correct before 1775.

Other scholars suggested the great American-born British cartographer Dr. John Mitchell (1711-1768) as the author but he died seven years before the book appeared in print and it includes quotes from sources published after his death. His name is misspelled “Mitchel” when his previously anonymous works are cited in American Husbandry. Even his biographers do not attribute the book to him. Other persons suggested and dismissed as the author include Georgia colonial agent Dr. John Campbell (1708-1775) and Campbell’s relatives, the prominent Edmund, Richard, and William Burke.[2]

The answer to the authorship of this monumental work is more than the end of a 238-year-old pursuit of a trivial fact. “An American” turns out to be a man of immense power and prestige who sought through his book to stop the creation of what became the United States only to later use his considerable influence for the benefit of the new nation!

Uncovering that identity required discovering a falsehood within a riddle concealed within the enigma of the secret author. American Husbandry includes, in the chapter on the colony of Georgia, a series of letters written to the book’s author. Identification of the anonymous letter writer led to the identity of the recipient, the anonymous “An American” who wrote American Husbandry.

The writer of the letters described in glowing terms success in agriculture on 6,340 acres on a small but navigable creek that emptied into the Savannah River, thirty miles west of Augusta, Georgia. From a home on the side of a hill, this planter had a view fromalmost every window of the “river” three miles away. The letter writer he had been in America for the previous eight years, but claimed to have previously lived in Scotland, England, the West Indies, Cadiz, and Naples.

In two instances, this planter wrote of living in Georgia but that cannot be the case – hence the falsehood. The colony’s extensive public documents eliminate any of its residents as the author of the letters, based on the details of location and the size of the holdings – ergo the riddle. If the plantation was actually located in neighboring colonial South Carolina, however, the information in the letters correlates with an identifiable planter. Knowing who wrote the letters then points to the identity of the 238-year-old enigma of who received them, “An American.”

Why did the author of American Husbandry alter the text of the letters to mislead the reader about which colony contained the plantation? The simplest explanation is that, having already filled five chapters on South Carolina, the author needed something for his chapter on Georgia. “An American,” judging by the chapter’s introductory remarks, lacked credible information about the topography, soil etc. of that colony.

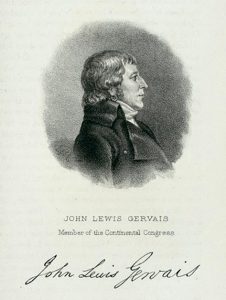

Searching the extensive colonial records of South Carolina uncovered only one person who matched the details in the letters in American Husbandry, John Lewis Gervais (1741-1798); no others came close. Born in Ganges, Languedoc, France, he was a Huguenot mercenary from Hameln in Hanover-Brunswick, a German state ruled by George III of Great Britain. Richard Oswald (1705-1784) hired him as magazine clerk and manager of the granary in Hameln that supplied the King’s army. Gervais subsequently traveled on both sides of the Atlantic in Oswald’s service, surely to the places mentioned as also known to the writer of the letters.

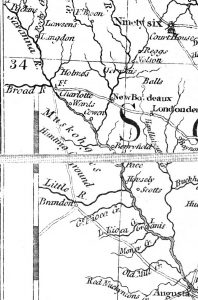

On June 28, 1764, Gervais arrived in Charleston to establish a reserve for German Protestants on the American frontier. It was an entrepreneurial and humanitarian project for Oswald done in cooperation with Oswald’s American partner Henry Laurens (1724-1792) of South Carolina. Gervais started with a tract of 5,000 acres near Long Cane Creek in today’s Greenwood County, west of modern Verdery, as described in the letters in American Husbandry. Reedy Branch was the small but navigable creek that emptied into the Savannah River and the deep and wide Long Cane was the “river” described as three miles away. Eventually Gervais’ holdings reached 6,340 acres, exactly the area indicated in the letters.

Other details also match what the anonymous planter wrote about his life and holdings. The letter writer mentioned a French neighbor who had sent home for grape vine cuttings, and of his own plans for making wine. Louis LeCerc Milfort, passing through the Long Cane-Hard Labor Creek area on the eve of the American Revolution, wrote of Gervais’ neighbor, French schoolteacher Jean Louis de Mesnil du St. Pierre, making unsuccessful efforts at producing wine from grapes transported from St. Pierre’s native Bordeaux. Gervais by then also had vineyards.

As the letter writer in American Husbandry, Gervais mentioned experimenting with silk production. One source claims that Oswald intended for this plantation to profit from Britain’s bounty on indigo production. Laurens wanted to send Oswald’s slaves there from the coast to improve their health and for their “happiness.”

Problems with communications and the American Revolution, however, prevented the transplanting of Europeans to these frontier lands. The plantation did have over 240 people living on it by February 1768. Two decades later, Laurens made an unsuccessful attempt to deed two thousand acres of the property as a settlement for North Carolina Moravians, Americans of Central European Protestant ethnicity like those families that Oswald had originally intended to settle there.

John Lewis Gervais prospered in the backcountry, however. Henry Laurens wrote that the plantation produced indigo, hemp, wheat, black cattle, sheep, hogs, horses, and potash. Gervais built a gristmill, became a justice of the peace, and bought a partnership in Andrew Pickens’ trade with the Cherokee Indians. The famed naturalist William Bartram witnessed Gervais officiating at a wedding at the Whitehall home of prominent frontiersman Andrew Williamson, later a brigadier general in the American Revolution.

Gervais served South Carolina in many public posts including feeding the American army and arranging for South Carolina to receive a loan from Dutch lenders. During the war, he lost almost everything he owned, including his slaves, except for his land. He particularly blamed his losses on neighbors who had supported the King but especially Williamson and Williamson’s secretary Malcom Brown, both English born. Gervais claimed that they had abandoned the Revolution to cooperate with the British military (scholars still debate whether Williamson committed treason). Ten years after the war, he was still trying to receive promised compensation for what he did for South Carolina.

After the war, John Lewis Gervais served in the Confederation Congress of the United States in 1782-1783 and he helped in the location of Columbia as South Carolina’s capital where a street carries his name. He moved to Charleston where he died on August 18, 1798.[3]

That Gervais surely wrote the letters published in American Husbandry makes Richard Oswald the prime candidate as the overall author/compiler of that book. Evidence that he was “An American” is extensive. In the 1730s-1740s, he lived for six years in the mid-Atlantic colonies, just as the author of American Husbandry had done.

Returning to his native Scotland, Oswald built a worldwide trading empire upon African slaves, American sugar, Asian tea, and much more. As a prime factor in Britain’s African slave trade, he transported almost 13,000 slaves to the New World, over 8,000 of whom his partner Henry Laurens sold. He was a true man of the world who famously asked for advice on Italian marble for his mansion in Scotland from his agent in India who bought him his Chinese slaves!

“An American” described the letters from the planter in American Husbandry as produced “from a pretty long correspondence carried on with a view of settling a relation in Georgia (which is since done).” In 1774, Richard Oswald settled his ailing cousin Capt. Oswald Campbell (died 1777) on the Oswald-Laurens-Gervais frontier holdings in an unsuccessful effort to improve Campbell’s health.

Oswald had all of the qualifications to have written American Husbandry. He read widely, consulted experts, and acquired an in-depth knowledge of subjects such as agriculture. His acquaintances included such great thinkers of his day as Arthur Young, Dr. John Mitchell, and Adam Smith.

This man of wealth and power likely avoided showing the manuscript of American Husbandry to experts like Arthur Young, however, or anyone who could have later revealed him as the author. For that reason, he might not have known to avoid repeating Young’s misinformation about sugar production.

A man in Oswald’s position had reason to publish his views on the colonies anonymously and later to not take credit for the authorship (although he died only nine years after the book appeared in print). By 1774, the British public and press had largely turned on America as civil war with the colonies seemed eminent. British people saw the Americans as ungrateful and without real cause for complaint.

Oswald’s acquaintance Benjamin Franklin appeared before the King’s Privy Council on January 29, 1774 to make a plea to keep the American mainland colonies in the British Empire. The council would not let him speak but ridiculed the previously venerated Dr. Franklin, even to calling him a traitor, as did the press soon after.[4]

Richard Oswald avoided public attention but royal officials sought his advice on America, even on bringing Russia into the war as a British ally. He obliged many times but only in private and with promises of anonymity. He even proposed a “Southern Strategy” of restoring a colony like South Carolina to the Crown as a model of reconciliation.

The British government and army, however, did not follow a hearts and minds strategy but continued to try to force the Americans back to their “duty.” Oswald wrote to his partner Henry Laurens, by then the president of the Continental Congress, endorsing the proposals of the Carlisle Peace Commission. That effort failed, in part, because Britain would not recognize American independence.

In late 1782, King George III called upon Richard Oswald, now almost eighty but still Britain’s greatest authority on America, to approach Benjamin Franklin about negotiating peace. He took with him to France a copy of his late friend Dr. John Mitchell’s famous 1755 map of America, with his own annotations, for use in the negotiations. Oswald played major roles in the subsequent treaty that ended the war, from the first meeting with Franklin to the final signing in his rooms in Paris more than a year later. Had the British leaders known of his authorship of American Husbandry and how it demonstrated his apparent love of America and sympathy with the Americans, however, they surely would not have allowed him to participate in the Treaty of Paris.

British critics of the negotiations from the beginning did criticize Oswald for giving away too much too easily to the Americans, including recognition of independence of the United States. He sought open trade between an independent United States and Great Britain and he predicted the so-called special relationship of Great Britain and the United States that, since the 1830s, has served the two nations to the present-day. Had British leaders followed his advice, the War of 1812 would never have happened. Benjamin Franklin praised his integrity.

Oswald did allow Laurens to add a clause to the Treaty of Paris to return to the Americans the slaves who had escaped to the British army. This was done to help Gervais to pay debts from their backcountry plantation project (that article of the treaty went ignored by the British army, however).[5]

Despite his advanced years, Richard Oswald actually considered moving to his land on the frontier of South Carolina. The letters from Gervais included in American Husbandry years earlier likely inspired him. Laurens, on the other hand, had written to Oswald back then warning of the dangers of living on the frontier.

The greatest revelation within the enigma of American Husbandry is not the identity of the author but the irony that Richard Oswald, this until now anonymous writer who called for keeping the thirteen colonies in the British Empire, eight years later became a forgotten British founding father of the United States!

[FEATURED IMAGE AT TOP: A 1905 engraving of Carl Wilhelm Anton Seiler’s engraving of the preliminary signing of the 1783 Treaty of Paris; a portrait of Richard Oswald hangs over the fireplace. Source: Library of Congress]

[1] For a lengthier fully documented version of this history see Robert S. Davis, “Richard Oswald as “An American”: How a Frontier

South Carolina Plantation Identifies the Anonymous Author of American Husbandry and a Forgotten Founding Father of the United States,” Journal of Backcountry Studies 9 (Spring 2014), online at: http://www.partnershipsjournal.org/index.php/jbc

[2] “An American,” American Husbandry, ed. Harry J. Carman, (1775; rep. ed., New York, 1939), xxxix-lv.

[3] For Gervais and his relationships with Laurens and Oswald see Philip M. Hamer, et al, eds., The Papers of Henry Laurens, 16 vols. (Columbia, SC: University of South Carolina Press, 1968-2011).Oswald also tried unsuccessfully to establish a similar settlement in East Florida at Mount Oswald, today part of Tomoka State Park. Daniel L. Schafer, “`A Swamp of an Investment’: Richard Oswald’s British East Florida Plantation Experiment” in Jane Landers, ed., East Florida’s Colonial Plantations and Economy (Gainesville, Fl., 2000), 11-38.

[4] Gordon S. Wood, The Americanization of Benjamin Franklin (New York: Penguin Press, 2004), 146-47.

[5] For Oswald’s career see David Hancock, Citizens of the World: London Merchants and the Integration of the British Community, 1735-1785 (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1995). The Osher Map Library of the University of Southern Maine has the annotated copy of Dr. John Mitchell’s map of North America used by Oswald in the treaty negotiations.

Recent Articles

The Home Front: Revolutionary Households, Military Occupation, and the Making of American Independence

A Strategist in Waiting: Nathanael Greene at the Catawba River, February 1, 1781

This Week on Dispatches: Brady J. Crytzer on Pope Pius VI and the American Revolution

Recent Comments

"A Strategist in Waiting:..."

Lots of general information well presented, The map used in this article...

"Ebenezer Smith Platt: An..."

Sadly, no

"Comte d’Estaing’s Georgia Land..."

The locations of the d'Estaing lands are shown in Daniel N. Crumpton's...