Silas Deane assisted the Patriot cause as a congressman, merchant, and diplomat. In 1776, Deane undertook a mission to France as the Patriots’ official, unofficial envoy. Officially, Deane arrived in Paris to conduct business as a private merchant. Unofficially, the Second Continental Congress had tasked Deane with securing supplies for the army and presents for Native American peoples. Congress also asked Deane to make contact with King Louis XVI’s Foreign Minister, Charles Gravier, comte de Vergennes to determine whether France would recognize the colonies as an independent nation.

Silas Deane fulfilled all of the tasks Congress asked of him. His good relations with Vergennes kept France interested in the American cause. His success in acquiring and shipping war materiel to the Continental Army made the Patriot victory at Saratoga possible. And yet, Silas Deane stands in the shadows of early American history, victim of the jealousy and paranoia that pervaded Congress and took hold of other Patriot officials.

Rise of Silas Deane the Merchant

Silas Deane led an exceptional life. Born the son of a blacksmith in Groton, Connecticut, Deane used his intelligence to obtain a full scholarship to Yale College; he graduated in 1758. After Yale, Deane studied law. He gained entry to the Connecticut bar in 1761. At the urging of fellow Yale graduates, Silas opened his law practice in Wethersfield, just south of Hartford, in 1762.

During the course of his work, Deane befriended Mehitable Nott Webb, widow of Joseph Webb, a prominent merchant who had been involved in the West Indies trade. Deane assisted Mehitable with settling her late husband’s estate. The couple grew fond of one another and they married in 1763.

Deane’s marriage to Mehitable Webb proved advantageous. Deane took charge of Joseph Webb’s thriving business and gained the connections and financial resources he needed to become a merchant in his own right. Deane excelled as a merchant. By 1767, he had earned enough money to begin building a grand home next door to Joseph Webb’s stately house.

Deane needed a new home. He had moved into Webb’s House after his marriage to Mehitable. The couple shared the home with Webb’s six children and their young son Jesse. Aside from cramped living quarters, Mehitable died in 1767 and Webb’s eldest son Joseph Jr. stood to inherit the house when he came of legal age in just a few years.[1]

Deane built a house that befitted his stature as one of Connecticut’s wealthiest merchants. Completed in 1770, the home featured a one-of-a-kind design. Deane departed from the popular Georgian architectural style of the time and built his house with an asymmetrical façade, a large veranda, and a bright yellow exterior. The house stood as a symbol that Deane had risen far above his humble origins as a blacksmith’s son. Unfortunately, Mehitable never had the opportunity to see the completed.

Deane entered politics after Mehitable’s death. In 1768, he won election to the Connecticut General Assembly. In December 1769, his neighbors appointed him to the Wethersfield Committee of Correspondence, which they tasked with organizing and coordinating the non-importation efforts of the community.

Deane excelled in politics just as he had as a merchant. In 1769, he expanded his political and commercial networks by marrying Elizabeth Saltonstall Evards, a socially well-connected and rich widow, who also happened to be the granddaughter of a former Connecticut governor.

Silas Deane, Continental Congressman

In 1774, the Connecticut General Assembly chose Silas Deane to be one of the colony’s three delegates to the First Continental Congress in Philadelphia. Many of the Continental Congressmen befriended Deane; he had an amiable personality, keen intelligence, strong work ethic, and a forgiving nature that made him likable. Deane’s positive service in the first Continental Congress and his political connections prompted the Connecticut General Assembly to re-appoint him to the Second Continental Congress in 1775.

Deane’s work in the Second Continental Congress involved a lot of behind-the-scenes committee work. Deane assumed this work naturally. As a member of the Connecticut Committee of Correspondence, Deane convinced his fellow committee members that Connecticut should coordinate an attack on Fort Ticonderoga to secure much needed arms, cannon, and ammunition for the Patriots. Connecticut organized a force comprised of Massachusetts militiamen and Green Mountain Boys under the joint command of Benedict Arnold and Ethan Allen to take the fort. When news of the successful seizure reached Deane in Philadelphia, his elated colleagues dubbed him “Ticonderoga.”

Deane’s committee work in Congress led to the creation of the United States Navy and to Israel Putnam’s appointment as George Washington’s second-in-command. Deane’s involvement with the latter effort cost him his congressional seat. Many Patriots throughout Connecticut and in the Connecticut General Assembly had wanted David Wooster appointed second-in-command. Unable to trust that Deane would represent their interests, the Connecticut General Assembly did not reappoint Deane to a third congressional term.

Silas Deane, Secret American Envoy to France

Although disappointed that he would not return to Congress, Deane worked diligently to complete his committee work before he left Philadelphia. His work on the Secret Committee of Correspondence, the Secret Trade Commission, and as the Chair of the Ways and Means Committee brought him the notice and friendship of Benjamin Franklin, Robert Morris, and John Jay. They appreciated Deane’s hard work and they feared losing a colleague who had a lot to offer the Patriot cause. As the Continental Army needed supplies and Congress wanted foreign support, these men approached Deane with a job that befitted his organizational, mercantile, and intellectual talents: Secret Envoy to France.

On March 2, 1776, the Committee of Secrecy presented Deane with a vaguely worded commission to serve as secret envoy. Officially, the Committee asked Deane “to transact such business, commercial and political, as we have committed to his care in behalf and by the authority of Congress of the thirteen united colonies.” Privately, Franklin, Morris, Jay and the other committee members instructed Deane to travel to France and acquire on credit all the arms, uniforms, and equipment he could for an army of 25,000 men. The Committee also gave Deane $200,000 in Continental bills to purchase gifts for Native American peoples Congress wished to keep friendly, or at least neutral, relations with. They instructed Deane to transact his business “in the character of a private merchant.” They also directed him to meet with Foreign Minister Vergennes and inquire whether France would recognize the colonies as an independent nation and sign treaties of commerce and alliance when, and if, Congress declared independence.[2]

The Committee requested a lot of Deane. They asked him to undertake a dangerous sea voyage, initiate diplomatic relations as the official, unofficial American envoy, and use his personal reputation and finances to help secure the credit and supplies Congress and the Continental Army needed. Deane had a strong work ethic and a keen intellect, but in a letter to his wife, he acknowledged that he seemed like an odd choice for the duties; he lacked diplomatic training, had never traveled beyond Philadelphia, and did not speak French. Regardless of these reservations, he agreed to undertake the mission.

Deane arrived in Paris in mid-June 1776. Over the course of eighteen months, he accomplished everything that Congress had asked of him. He initiated a contact with Vergennes, purchased and coordinated the shipment of military supplies with Pierre-Augustin Caron de Beaumarchais (a merchant who assisted Deane with the French crown’s covert assistance), and kept the United States in good standing with the French government. In order to accomplish the latter task, Deane had to accept meetings with French military men whom the Crown wanted to receive commissions in the Continental Army.

The French desire to see the United States offer military commissions to its aristocrats and military officers placed Deane in a difficult position. Congress had not authorized Deane to commission foreign officers. However, Vergennes made it clear that he wanted Deane and Congress to grant these favors. Although Deane wrote to Congress about the issue numerous times, he never received instructions.

Increased patrols of the Atlantic Ocean by the British Navy made communication between Deane and Congress intermittent at best. For example, Congress mailed Deane a packet containing an official copy of the Declaration of Independence on August 7, 1776. Deane did not receive it until November 16. Parisian newspapers reported that the United States had declared independence more than a month before Deane received an official copy of the Declaration to present to Vergennes. Unsure of what to do with the officers Vergennes sent him, Deane granted the commissions to keep Vergennes and King Louis XVI happy. Deane hoped that Congress would sort out what to do with the commissions when the officers arrived in the United States.

On December 4, 1776, Deane received unexpected news. Benjamin Franklin had arrived in France with a commission that named Deane, Franklin, and Arthur Lee official United States emissaries to France. The three men opened formal negotiations with Vergennes for a treaty of amity and commerce between France and the United States, but neither Vergennes nor the King wanted to ally with the United States until the Continental Army proved that it could defeat the British Army.

The proof they needed arrived in December 1777. The ships Deane and Beaumarchais had laden with supplies and dispatched to the United States arrived in Portsmouth, New Hampshire throughout May and June 1777. Word that the Continental Army had enough guns, cannon, uniforms, and gunpowder to outfit an army of 30,000 men spread throughout New England and New York as the supplies made their way into the Hudson Valley. Thousands of men flocked to join Horatio Gates’s ranks. The Patriots used Deane’s supplies to defeat Burgoyne and his British regulars at Saratoga in October 1777. As soon as word of the American victory reached France, Vergennes agreed to negotiate treaties of amity, commerce, and alliance between France and the United States.

The Recall of Silas Deane

The youngest brother in a family of powerful and influential men, Arthur Lee eyed Silas Deane with jealousy. Lee had wanted to negotiate lucrative military supply contracts with the French and reap the 5 percent commission Congress had allowed Deane on all purchases. Throughout 1777, Lee wrote to his brothers Richard Henry and Francis Lightfoot in their capacity as Continental Congressmen, alleging that Deane acted in his own interest rather than Congress’s. One allegation claimed that Deane had planned to pocket £200,000 in loans that Vergennes had provided to Deane for the purchase of supplies. Deane informed Congress of Vergennes’s loans, but Lee claimed that Deane had misled them; Vergennes had not loaned, but gifted the monies to the United States.

Lee’s letter campaign obtained its desired end. Frustrated that Deane had issued so many military commissions without permission and fearing that Lee’s accusations of fiscal mismanagement might have merit, Congress recalled Deane. Its orders reached Deane in early 1778, just two weeks before he, Franklin, Lee, and France planned to celebrate the conclusion of their treaties with the three envoys’ official presentation to King Louis XVI.

Deane informed Franklin and Vergennes of his recall. Vergennes gave Deane a letter to present to Congress that stated his satisfaction with Deane and acknowledged that Deane had performed his duties with such “zeal, activity, and intelligence” that he had “merited the esteem of the King.” Deane returned to the United States after his presentation to the king. He sailed aboard the Languedoc, flagship of the French fleet that Admiral comte d’Estaing brought to assist the United States in its fight against the British Navy.[3]

Deane arrived in Philadelphia on July 14, 1778. He requested an interview with Congress and then settled into the home of his friend Benedict Arnold while he awaited his audience.[4] Congress made Deane wait for more than a month before it ordered him to appear.

Deane spent months trying to clear his name. He asked Congress for permission to return to France so he could settle his affairs; they refused. Frustrated, Deane published a 3,000-word essay in The Pennsylvania Packet that decried the factionalism within Congress. Embarrassed, Congress gave Deane leave to return to France and tacitly acknowledged that Arthur Lee had lied about Deane’s fiscal mismanagement, but they stopped short of clearing Deane’s name.

Deane returned to France discouraged, depressed, and broke. Arthur Lee and Congress had cast aspersions on his good name. His work on the behalf of the United States had forced him to both rely on his personal finances and neglect his personal business. Unable to afford the high cost of living in Paris, Deane removed to Ghent in 1781. Deane had hoped to start a new business venture, but few opportunities materialized.

Between May and June 1781, Deane wrote despondent letters to friends and family that decried Congress. His missives contained sentences such as “I find that an independent democratical government is not equal to the securing of the peace, liberty, and safety of a continent like America.”[5] Deane wrote his sentiments as private and therapeutic diatribes between friends; however, the British intercepted Deane’s letters and published them in London newspapers. Deane became persona non grata in the United States.

In 1783, Deane moved to London hoping to restart his mercantile career. His old friend Benedict Arnold greeted him. Although Deane had told Arnold to leave him alone, reports of Arnold’s visit circulated and their perceived association further damaged Deane’s reputation.

By 1789, Barnabus Deane asked his brother to come home. On September 23, 1789, Deane boarded a ship bound for Connecticut. Four hours into the voyage, he collapsed and died. The ship returned to port and left his body to be interred in an unmarked grave in Deal, England.[6]

The Vindication of Silas Deane

In 1840, Silas Deane’s granddaughter, Philaura Deane Alden, petitioned Congress to finish its audit of her grandfather’s accounts. Congress appointed a committee which studied all available accounts related to Deane’s wartime transactions. On February 17, 1841, the House of Representatives Claims Committee reported that Deane had acted honorably and had not mismanaged funds. On August 10, 1842, President John Tyler signed “An Act for the Settlement of the Accounts of Silas Deane.” The Act permitted Congress to pay Alden $37,000 that it owed Silas Deane.[7]

The House of Silas Deane

The legacy of Silas Deane is carried on in the state-of-the-art house that Deane built between 1767 and 1770. Today you can visit the Deane House, which forms one-third of the Webb-Deane-Stevens Museum, a group of three early American houses owned and operated by the National Society of The Colonial Dames of America in the State of Connecticut. Charles T. Lyle, Executive Director of the museum, has furnished the Deane House to portray the lavish life Silas Deane lived before he departed for France.

Enthusiasts of early American history will appreciate the grandeur of Deane’s home as soon as they step into the spacious foyer. Although you will be tempted to climb the grand staircase to your right, you should start your tour in Deane’s best parlor to your left which will impress you with its size and detail. For example, above the fireplace you will notice that Deane installed a Brownstone mantel which he acquired from Portland, Connecticut.

A back room stands behind the parlor. The room may have served as many as three distinct purposes. Deane may have used the room as a home office. His family may have utilized it as a private dining room. The built-in murphy bed suggests that the Deanes may have also used the room to host an occasional overnight guest.

Lyle has staged the large, formal dining room to look as it did when the Deanes hosted friends, family, and important guests. In 1775, George Washington and John Trumbull both dined there; Deane had befriended Washington during the First and Second Continental Congresses. In June 1775, Deane wrote his wife Elizabeth and asked her to take care of Washington and his retinue as they made their way to Cambridge, Massachusetts. Although there is no a diary entry from Washington, evidence about his stay strongly suggests that he spent a night in the Deane House. Washington certainly stayed overnight in the Joseph Webb House next door, where he and Rochambeau planned their final action against the British Army in May 1781.

A large kitchen stands at the back of the Deane House. The kitchen reflects that Deane intended to host large and lavish dinner parties; the room’s size made it possible for his slaves to produce large quantities of food at once and tools like the spitjack increased their efficiency by allowing them to keep the rotisserie turning while they prepared other dishes. Silas and Elizabeth had as many as eight slaves at their disposal for such tasks.

Elizabeth Deane’s two personal slaves, Hagar and Pomp, likely shared the bedroom at the top of the rear stairwell. The room contains older furniture, a reflection of the types of furnishings the Deanes may have provided for favored slaves. Pomp and Hagar’s room stands within a few feet of the Deanes’ master bedroom. Elizabeth suffered from frequent bouts of illness and she kept Hagar nearby to help her when she felt unwell.

You will find the front guest chamber to be the most impressive feature in this house built to impress. In addition to using this room to host out-of-town guests, the Deanes used it to host large parties and dances. The room reflects Deane’s thoughtful design. When you enter, try and imagine what the room would have looked like during a party. The Deanes’ slaves would have removed all of the bedroom furniture, which would have made the room feel larger. The long, continuous floor boards under your feet extend the room into the upstairs foyer. The long floorboards add a natural depth to the room as well as a slight spring to any dancer’s step. The Deanes would have placed the musicians they hired at the end of the upstairs hallway. As guests ascended the grand staircase into the ballroom, they would have appreciated the excellent acoustics Deane designed into this space.[8]

Silas Deane put a lot of thought and money into his house. It stands as an impressive monument to him, his keen intellect, and his success as a merchant. The house also inspires visitors to consider Deane’s efforts in France. Not only did the supplies he obtained contribute to victory at of Saratoga, Washington and Rochambeau met as a result of Deane’s exertions in bringing about a French alliance. It is fitting that the two generals planned the final action of the War for Independence just next door to Silas Deane’s house.

Conclusion

The efforts of Silas Deane affected the alliance between France and the United States. Deane used his reputation and talents as a merchant, and his personal wealth, to secure and ship supplies to the Continental Army that enabled them to win at Saratoga. News of the victory prompted treaties of amity, commerce, and alliance between the United States and France.

Notwithstanding Deane’s success, he was recalled. Irregular communication between Deane and Congress led Deane to issue military commissions to French officers and aristocrats without congressional authority. Infrequent mail deliveries made it impossible for Congress to know why Deane had sent so many foreign military officers, prompting some in Congress to believe that Deane issued them for personal rather than public interest. The ranks of doubters grew with each letter Congress received from Arthur Lee.

Neither Deane nor Congress handled the recall well. Although Deane returned as requested, many congressmen proved unwilling to hear his explanation, making him wait months for a proper audience and then hearing him only after Deane’s public call to action in the newspaper. Congress gave Deane his interview, but refused to clear his name. Despondent, Deane transformed from the amiable man who had embraced the Revolution during its earliest days into the dejected man who questioned its cause. In the end, his frustrated and faithless words combined with Congress’s spiteful refusal to clear his name to cast Silas Deane into the shadows of early American history. As a result, Silas Deane has become a forgotten Patriot.

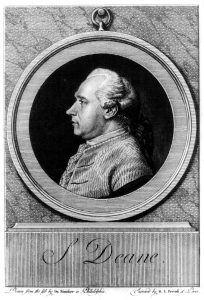

[FEATURED IMAGE AT TOP: 1766 Portrait of Silas Deane by William Johnston. Current location: Webb Deane Stevens Museum]

[1] Charles T. Lyle, “Silas Deane: Patriot and Statesman,” Webb House Courtyard Kiosk Panel 2.

[2] Benjamin Harrison, John Dickinson, and Thomas Johnson served as the other members of the Committee of Secrecy. Joel Richard Paul, Unlikely Allies: How a Merchant, a Playwright, and a Spy Saved the American Revolution, (New York: Riverhead Books, 2009), 128; Office of the Historian, “Secret Committee of Correspondence/Committee of Foreign Affairs, 1775-1777,” U.S. Department of State Office of the Historian, https://history.state.gov/milestones/1776-1783/secret-committee

[3] Charles Gravier, comte de Vergennes, “Count de Vergennes to the President of Congress, March 25, 1778,” in Jared Sparks, The Diplomatic Correspondence of the American Revolution : Being the Letters of Benjamin Franklin, Silas Deane, John Adams, John Jay, Arthur Lee, William Lee, Ralph Izard, Francis Dana, William Carmichael, Henry Laurens, John Laurens, M. Dumas, and Others, Concerning the Foreign Relations of the United States during the Whole Revolution: Together with the Letters in Reply from the Secret Committee of Congress, and the Secretary of Foreign Affairs: Also, the Entire Correspondence of the French Ministers, Gerard and Luzerne, with Congress, vol. 1 (Washington: J.C. Rives, 1857), 88.

[4] Arnold served as the military governor of Philadelphia between 1778 and 1780 while he recovered from the leg wound he received at the Battle of Saratoga.

[5] David Drury, “The Rise and Fall of Silas Deane, American Patriot.” Connecticut History, http://connecticuthistory.org/the-rise-and-fall-of-silas-deane-american-patriot/

[6] Paul, Unlikely Allies; Drury, “The Rise and Fall of Silas Deane; Charles T. Lyle, “Silas Deane House,” Webb-Deane-Stevens Museum, http://webb-deane-stevens.org/historic-houses-barns/silas-deane-house/

[7] Laws of the United States of America: From the 4th of March, 1789, to the [3rd of March, 1845]: Including the Constitution of the United States, the Old Act of Confederation, Treaties, and Many Other Valuable Ordinances and Documents; with Copious Notes and References (Philadelphia: J. Bioren and W.J. Duane, 1845), 269.

[8] Lyle, “Silas Deane House.”

6 Comments

Elizabeth, thank you for an interesting summary of Deane’s life. In my research of the American Commission in Paris, my conclusion was that Franklin and Beaumarchais were the major figures responsible for the “covert” assistance provided through the front company Hortalez & Company, with Robert Morris at the colonial end unsuccessfully trying to get agricultural products from the various colonies to pay for the supplies. While Deane started the negotiations for the substance of the program, Franklin gave it momentum and direction. Also, I believe Dr. Edward Bancroft, the British spy who was the private secretary to the Commission, played a role in motivating Deane to write the 1781 letters.

Ken, you may be right about Bancroft. There are so many twists and turns in the Deane story I had to leave many of them out.

In the literature I read on Deane, Deane and Beaumarchais did the bulk of the work to get the supplies. Franklin had set Deane up with his friend Dubourg and Bancroft. With that said, you may know more than I do on this subject. I conducted mostly secondary source research about Deane so that I could explain why his house is worth visiting.

This article not only restores our collective memory of Deane but also reaffirms the sometimes questioned importance of the Northern Army’s successes at Saratoga in convincing the French to assist the United States.

Thank you for a very interesting article on a name we hear of yet are vaguely familiar with. Really a true patriot, it is our Nation`s misfortune that Silas Deane was handled so poorly by Congress. Evidently the foibles and iniquities of Congress 240 years ago continue in good tradition today!

John Pearson

Thanks Elizabeth. I am a teacher in Colorado (8th grade as well as utilizing my masters in the community college setting) I am trying to nail down the story of how the revolution produced the ingredients for the ability to develop a navy able to defeat the British in 1812. My focus is the privateering aspect of the revolution and the international intrigue led by Franklin to bring in France with their Navy. So Silas features prominently and I am keepiing in mind my professors admonitions to not be totally reliant on primary material but to incorporate secondary scholarship as well. (long winded way of saying nice summary of Deane to answer my question of why this guy?)

As a descent of Silas Deane, I wish to thank all those who had the dedication and commitment to do a “Deep Dive” into the truth behind the unwarranted slander against Silas Deane.

Vikki Deane Wright