On Tuesday, October 9, 1781, at 5:00 that afternoon, as an American flag unfurled over Grand Battery 13A at Yorktown, George Washington personally set light to an eighteen-pounder announcing to Charles Cornwallis that his end was not far off. As the hurtling ball spent itself, it left behind a wake of devastation killing the British Commissary-General and injuring two other officers gathered together for their evening meal. For Massachusetts officer Lieutenant Colonel Ebenezer Stevens, in charge of attending Henry Knox’s artillery park that day, it was no doubt an eminently satisfying result.[1]

While the thirty-year-old Stevens already possessed an extraordinary amount of experience in the patriot cause as an early leader at the Boston Tea Party, a member of the Quebec expedition and later assuming the duties as the leading artillerist of the Northern Department, witnessing the final moments of the war surely ranked high on his list of achievements. However, had he known what was taking place back home at that very moment, where the “fruits” of the conflict he was helping to bring to an end were beginning to make themselves known, he could be excused if he paused to reflect on what it all meant for his nation’s future.

The year 1781 marks not only the end of wholesale fighting in North America, but also the unveiling of other unanticipated and unforeseen forces about to radically change the patriots’ perceptions of what the Revolution was all about. From a large, macro perspective, this was the year that the Articles of Confederation, first drafted in 1777, were ratified in March resulting in the creation of what proved to be a largely ineffective federal government that did little to inhibit the sovereignty that the individual states continued to cling to. And on the micro level, much was also amiss.

For Washington, until the British menace resolved itself, it remained a difficult proposition for him to man and equip his army as he continued to rely on the benevolence of hard-pressed states to provide necessary requisitions. Notwithstanding the disbanding of several Massachusetts regiments in January 1781, the repeated calls for individual towns to fulfill their assigned allotments represented a continuation of a way of life stretching back to 1775. For just the town of Groton, Massachusetts, a March 1 itemization of residents’ tax obligations reveals a staggering toll being extracted from them for “soldiers notes, repair of bridges, mending highways, soldiers families, school, horses for the Continent [Army], town’s poor, assessors’ wages, clothing for the army, town’s expenses, counterfeit money, beef notes, treasurer’s fees,” all amounting to £41,057. Then, they were required by the General Court to provide 8,845 pounds of beef, thirty-seven shirts, nineteen blankets and seventeen men.[2] With six years of incessant demands placed upon them, there was bound to be some display of discord and now, with the war ending, the next moment of difficulties and hardships had arrived, one that some historians have termed America’s “Critical Period.”

The absence of a uniform financial system at the war’s outbreak was at the base of many of the problems, playing havoc with colonists’ ability to fund the patriot cause as its many deficiencies became frighteningly known by 1781. Federal supremacy allowing for a comprehensive monetary scheme remained a chimera as the Continental Congress pleaded for assistance, relying on the individual states to come up with ways to fund their many demands. Massachusetts already had extensive experience in caring for itself, having launched its own military forays against the French and Indians during the earlier wars for empire, so the latest stresses placed on it were not particularly new.

Following the events of April 1775, Massachusetts became the first colony to officially issue bills of credit to finance her militia and support the war effort, with other colonies following in like fashion. Known variously as bills, indented bills, bills of credit, certificates (so-called “legal tender” that creditors were required to accept for payment of debts), they served as an alternative method to conduct transactions, replacing the use of scarce specie or having to pay with country goods, i.e., cattle, crops, etc. Concurrently, the Continental Congress also began to issue its own currency in various denominations, known as Continentals. As the war progressed the various combinations of currencies fluctuated wildly, made all the more dire by ill-advised legislative efforts to assign values to them that refused to remain static and a massive counterfeiting operation put in place by the British.

The effects of an unpredictable financial underpinning to the country’s efforts brought disillusionment and distrust to many. Investors found that they could not depend on promised return of monies they initially loaned to the war effort, soldiers could not trust that they would be compensated resulting in refusal to serve or in desertions, housewives could not predict their families’ income and expenditures with certainty, and farmers had to sell livestock to cover deficiencies.[3]

With no overarching authority telling it that it could not do so, in January 1781, only two months after ratifying its constitution, Massachusetts decided to restrict the use of legal tender, both national and state, refusing to require merchants to accept it at face value and forcing the debtor to provide enough of it to equal the prevailing market value of gold and silver.[4] Restricting the applicability of the tender act was received in various fashions, with city-dweller Abigail Adams writing to John that “I have the pleasure to inform you that a repeal of the obnoxious Tender Act has passed the House and Senate.”[5] However, not everyone was happy.

The effect of the repeal caused hardship for those in the country where many farmers had actually grown dependent on the new emissions to conduct their transactions in an environment allowing little access to specie. Together with markedly increased taxes (more than three to five times higher than under British rule) and dwindling value of the script in circulation, the sudden removal of any requirement that creditors accept it caused great alarm.[6] Then, on August 7, because of “large and pressing demands upon this Commonwealth for money … to purchase supplies for the army,” the Massachusetts Council ordered collectors and constables to immediately begin their next sweep of the countryside to gather taxes.[7] In accompaniment with so many other demands, this appears to have been one of the more noteworthy events heralding the arrival of the Critical Period, in Massachusetts at least, just as Washington was trying to close out the war.

The following month, on September 24, residents in Groton met once again because “the credit of paper money [was] failing” and they needed to decide if assessors would be allowed to collect £840 hard money for taxes in lieu of just over £1,573 in new emission paper currency. Issues of public safety were also on the rise as they considered

… if the town will direct the constables to take orders upon the town treasurer from such persons as have notes for money or grain due from the town in discharges of their rates, or direct the constables to wait upon such persons for their rates until further order, and act anything upon this article as may appear to be for the interest and safety of the town and such individuals as are particularly concerned….[8]

The result was a denial of any substituting hard money for paper currency to pay the tax and the meeting was quickly adjourned. However, they met again on the 28th and reconsidered their prior vote, this time agreeing to allow for the raising of £500, presumably in hard money. Concerning any stay in the constables’ collection efforts, the town chose to ignore the presence of the looming safety problem, voted to pass over the issue and adjourned. That same day, the General Court finally came to the realization that its balancing act with the new emission currency was failing and prohibited any further issuance or receipt of it.

The stage was now set for confrontation. Chaotic finances both in Boston and Groton, inconsistent and incoherent currency manipulations, continuing demands to support the war, and a refusal to provide direction to rate-gathering constables gave rise to a series of events in town that swept up even some of the most distinguished local inhabitants.

Captain Job Shattuck (half-uncle, seven generations removed from the author) was a highly respected town father, successful farmer, and the largest landowner (500 acres) in town. He also had an admirable militia record dating back to the 1755 Acadia campaign and had served during the Lexington Alarm, the Siege of Boston, and in defense the northern frontier at Mt. Independence and Ft. Ticonderoga. Now forty-five years old, a father of nine children, he was serving as a town selectman and on various important committees on the inhabitants’ behalf. He had also served several times in the unenviable role of constable, responsible for gathering in the onerous taxes that officials kept demanding of the people, thereby rendering his more recent actions something of note.

Twenty-nine year old William Nutting was one of Groton’s two constables in the fall of 1781. He had served as a corporal in one of the town’s two minuteman companies in 1775 and moved on to become one of the constables a few years later. An avid diarist, Nutting maintained a series of seventy-five small notebooks, each of several pages, between 1777 and 1804, describing life in rural Groton and providing many insights into his daily routine. A July 31, 1781, entry states that he paid Thomas Wasson “eight dollars & 6 coppers” as part of his bounty to enter into army service. His duties in the following days appear relatively uneventful until October 4, just as Washington was preparing the grounds in front of British fortifications in Yorktown, when he ventured onto the farm of Joseph Sheple. In lieu of the necessary pieces of silver, Nutting explained simply in his diary that he “took a pair oxen from Capt. Sheple for rates.”[9] The fuse had been lit.

Following Nutting’s visit, Sheple wasted little time in reporting the loss of his ability to make a livelihood, immediately conferring with friends. The events taking place four days later, the first of several occurring that month and which came to be called the “Groton Riots,” were described by Nutting in cryptic, understated fashion, “Monday, the 8th – the oxen were redeemed by Mr. Child, Mr. Fletcher & Capt. Shattuck.” However, an “Indictment for a Riot” filed later that month by authorities expanded significantly on the event, describing something just short of mayhem, one headed by none other than one of Groton’s selectmen,

The jurors of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts upon their oath presented that Job Shattuck of Groton, Gentleman, Oliver Parker, Gentleman, Oliver Fletcher, Yeoman, Cotton Proctor, Laborer, Nehemiah Gillson, Laborer, Jonas Green, Laborer, Stephen Munro, Husbandman, Ezekiel Nutting, Jr., Laborer, Royal Blood, Laborer, John Wood, Jr., Jacob Lakin Parker, Laborer, Eleazer Flagg, Moses Child, Gentleman, Daniel Williams, Husbandman, Isaac Bowers, Yeoman, Benjamin Lawrence, Gentleman, Ezra Farnsworth, and Jason Williams, Yeoman, together with many other persons to the jurors unknown being willfully disposed licentious persons and unmindful of their duty to support and maintain the due administration of the government of this Commonwealth … and also conspiring to disturb the peace of said Commonwealth, and to oppose and prevent the execution of the good and wholesome laws of this Commonwealth and to prevent and obstruct and the legal and regular collection of a tax legally assessed by virtue of a law of this Commonwealth, commonly called the Silver money Tax, being a tax assessed in lawful silver and gold money towards the redemption of the bills of credit issued on the fund of this Commonwealth on the eighth day of October current with force and arms, that is to say, with Staves and Clubbs … unlawfully, riotously and routously, did assemble and gather together for the unlawful purpose aforesaid and being so assembled, in and upon William Nutting … an assault did make and him the said William Nutting then and there did evilly entreat and obstructed and prevented him from collecting the tax aforesaid… to the disturbance and terror of many of the subjects of this Commonwealth….[10]

The unfolding of events is not difficult to imagine. When Sheple’s friends learned of his experience with the industrious Nutting, imaging what was in store for each of them when it came their turn, they turned to the respected Shattuck for guidance. Not willing to turn them aside, he led them as they set out to confront the hapless constable, “redeeming” back the confiscated oxen with their “Staves and Clubbs,” but without shedding blood. As traumatic as the events might have been for Nutting, it appears that no official recourse was taken against any of the eighteen men immediately afterwards, which, perhaps, only served to embolden them to further action.

Benjamin Stone, the second constable working in the southern part of town, became the next target. Only days after the British began to parlay for surrender terms on October 17, just as a supporting fleet departed in their direction from New York harbor to provide aid, on October 22 the band of men met once again. This time, they interfered with Stone’s tax collecting efforts, besetting him at some undisclosed location, still employing their staves and clubs as they engaged in riotous behavior; again no bloodshed occurred and no official action was taken.

On October 27, Stone tried once again to make his rounds, but, as before, met with the same group headed by Shattuck. However, on this occasion, their behavior was described as being in a “tumultuous manner for the space of two hours to the great disturbances and terror of some of the subjects of this state.” Stone had apparently not sufficiently understood the degree of opposition to his conduct during the first encounter so that he needed a substantial amount of time to have it forcibly conveyed to him; again, without bloodshed.

All of the men were indicted shortly thereafter and warrants were issued for their arrests the following February. When they appeared before the court in April, Shattuck and five others admitted to the offenses and various monetary fines were imposed. Those persisting with not guilty pleas went to trial, were either found innocent or guilty of riot or unlawful assembly, and paid varying fines and posted bond assuring their good behavior for the ensuing year. Why someone of Shattuck’s stature chose to interfere with the work of the two constables, a difficult occupation that he fully understood and appreciated, is not known, but it may have been because of so-called “fellow feeling,” or empathy for many in the frustrated farming community.[11] While the community appears to have forgiven those transgressions as demonstrated by their continuing to elect him to important positions, it was by no means the last example of his, and his friends’, display of unease with the new realities being thrust upon them.

No, the British surrender at Yorktown hardly signified the arrival of a time of peace or the ending of the peoples’ hardships. The disturbances taking place in Groton in 1781 were but one example of new world realities and the beginning of difficulties throughout the new states as people began to grasp the responsibilities that independence brought them. In Hampshire County, residents gathered in convention to address grievances relating to personal debt enforcement actions that were on the rise following the reactivation of courts silenced during the war years.[12] Issues concerning taxes assessed on the value of land verses the ability of the owner to pay resulted in distrust and allegations of fraudulent collusion taking place between collectors and purchasers at tax sales. One writer called for the General Court to institute reforms, skeptically questioning if that was even possible because its “regard to justice has been lately influenced in their religious act respecting the currency.”[13]

In 1782 local resident Rev. Samuel Ely instituted significant agitation aimed at the new state’s constitution. This resulted in rioting, calling out over 1,000 Hampshire County militiamen and the suspension of habeas corpus. Yet another series of protests broke out between 1783 and 1785 over issues relating to the military, pay for services provided by Revolutionary War officers, and the exclusivity of the Society of the Cincinnati. These widespread, uncoordinated spasms were significantly exacerbated thereafter with the onset of a recession. Finally, it all came to a crashing conclusion in the summer and fall of 1786 when Job Shattuck arose yet again, becoming an early protest leader in closing county courts in what came to be called Shays’s Rebellion; Shattuck was severely injured by government troops and replaced by Daniel Shays.

While the years between 1781 and 1787, started off by events such as the Groton Riots, hardly portended a good result, the creation of the U.S. Constitution and resulting cessation of the Articles of Confederation provided as more solid a foundation than the country had ever before had, and marked the end of this terribly difficult time.

Note: This article contains extracts from my book, Artful and Designing Men: The Trials of Job Shattuck and the Regulation of 1786-1787 (Mustang, OK: Tate Publishing, 2013).

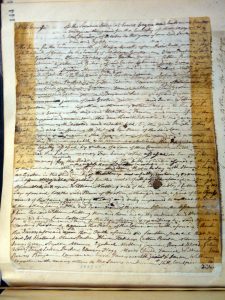

[FEATURED IMAGE AT TOP: Clerk’s entry identifying court papers relating to Groton Riots. Source: Massachusetts Archives, Suffolk Files Collection, vol. 1029, case number 148930, vol. 1039, case number 149717, and vol. 1042, case numbers 149860, and 149889; and, Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court Archives, vol. 1787, pg. 122.]

[1] Jerome A. Greene, The Guns of Independence: The Siege of Yorktown, 1781 (New York: Savas Beatie, 2005), 184, 191.

[2] Groton (MA) Town Meeting Minutes [GTMM], 2 vols., pgs. 378-389; Acts and Resolves, Public and Private of the Province of the Massachusetts Bay, (Boston: Wright and Potter, 1869), 643-679.

[3] SIDNEY, in Massachusetts Spy, March 1, 1781.

[4] Boston Gazette, January 22, 1781. It also issued an order to constables to immediately bring in the Silver Money Tax, one that had to be paid in difficult to find specie.

[5] Abigail Adams to John Adams, 28 January 1781 [electronic edition]. Adams Family Papers: An Electronic Archive. Massachusetts Historical Society. http://www.masshist.org/digitaladams/ [accessed May 2, 2014].

[6] Ralph V. Harlow, “Economic Conditions in Massachusetts during the American Revolution,” Publications of the Colonial Society of Massachusetts, vol. 20 (Boston: By the Society, 1920), 185-86.

[7] Continental Journal (Boston), August 23, 1781.

[8] GTMM, 384.

[9] Entry, October 4, 1781, William Nutting Diary, Massachusetts Historical Society.

[10] Commonwealth v. Shattuck, et. al., Middlesex, April term 1782, Suffolk Files Collection, vol. 1029, file 148930; Supreme Judicial Court Record Book, vol. 1787, 122, Boston, MA.

[11] Woody Holton, Unruly Americans and the Origins of the Constitution (New York: Hill and Wang, 2007), 116.

[12] Josiah Gilbert Holland, History of Western Massachusetts, Vol. I (Springfield: Samuel Bowles and Co., 1855), 230.

[13] Massachusetts Spy, May 10, 1781.

2 Comments

In spite of laws against “rioting,” there is considerable evidence that 18th-century English and Americans viewed it as an acceptable form of protest. Witness the numerous examples in the pre- and post-Revolutionary America (including this interesting one offered up by Gary), the Black Act riots in England, the Green Mountain Boys activities in the New Hampshire Grants, the anti-Shaker riots wherever they went, etc. In the vast majority of incidents, there may have been property damage but nobody suffered bodily injury.

One very minor note concerning the 1781 disbanding of the Massachusetts regiments: the whole Continental army underwent a reorganization at the start of that year. True, many regiments disbanded–ones from most states, not just Massachusetts–but the army had a glut of officers and only they went home. The enlisted men went to fill out the remaining regiments.

Mike,

Thank you for your point on the pervasiveness of “rioting” in the colonies.

Pauline Maier makes an important observation that these occasions served as, essentially, displays of a community’s consciousness in the absence of competent overall authority. When the elites failed to watch out for the common mans’ concerns, then it was not unusual to see these displays of disaffection. She further notes that post-Revolution, when independence had been gained and supposedly republican governments were being instituted, rioting became more suspect and not so easily tolerated. See, “Popular Uprisings and Civil Authority in Eighteenth-Century America,” The William and Mary Quarterly, Third Series, vol. 27, no. 1 (Jan. 1970): 3-35.

The Groton Riots fell within these two extremes, just as the war was ending and before responsible, popularly elected governments were instituted. The war years were ones in which the people were afloat without established laws and functioning courts allowing them some degree of predictability of their future. What I find interesting is the fact that responsible people, those with honorable military experience and holding high local civil positions (such as my relative Job Shattuck), chose to continue with the traditional rioting when they should have been contributing to stabilizing the new world the Revolution delivered. Clearly, much more work remained to be done (and it was several years before that happened) in getting competent, sympathetic legislators, and laws, put into place.

With regard to the disbanding of regiments in 1781, I suspect that many of these officers let go (or “deranged” in the term used at the time) became somewhat embittered by the experience as they were forced out and returned home. That is my sense with regard to several of the officers involved in the later protesting that arose in Worcester County at the time of Shays’s Rebellion in the summer of 1786.