On the chilly evening of January 18, 1776, Georgia’s royal governor, Sir James Wright, summoned Rebel leaders Joseph Clay and Noble Wimberly Jones to his home – on the corner of modern-day Telfair Square in Savannah – to discuss the recent arrival of a British fleet off the coast near Tybee Island. He informed them that the ship’s officers had been instructed to treat those in arms “as in a state of rebellion” and, if possible, “destroy their towns & property.”[1] But the governor promised the Rebels that if the ships were allowed safe anchor and were permitted to provision themselves at market value, he would “endeavor to settle” affairs with the British officers in order “to prevent their doing any injury to this town.”[2] The Rebel leaders made haste for Tondee’s Tavern, just a few blocks away at the northwest corner of Broughton and Whitaker streets, and informed the Council of Safety. In what was surely a tense discussion, they resolved to plunge Britain’s youngest colony deep into the maelstrom of rebellion by ordering the arrest of Governor Wright and the Provincial (royal) Council members John Mulryne, Josiah Tattnall, and Anthony Stokes because they were now deemed a dangerous threat to the liberty of the people.[3]

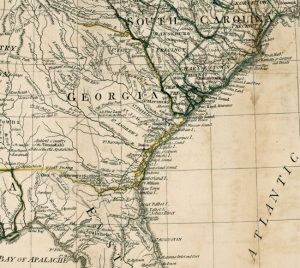

A condensed version of this story begins in the summer of 1775. The revolutionary fervor in Georgia had placed the continued royal governance of the colony in peril. Discouraged, exasperated, yet painfully lucid and insightful, Governor Wright scrawled a lengthy epistle to Lord Dartmouth, which vividly illustrated the rebellious inclination of a “junto of a very few only” who seek to undermine royal authority.

Every thing my Lord was done that could be thought of, to frustrate their attempt, but this did not totally prevent it…. I am to be reflected upon & abused for opposing the licentiousness of the people…. I apprehend there will be nothing but cabals & combinations and the peace of the province & minds of the people continually heated, disturbed & distracted and the proclamation I issued against [treasonous gatherings] is termed arbitrary & oppressive…. I conceive that the licentious spirit in America has received such countenance & encouragement from many persons, speeches, and declarations … that neither coercive or lenient measures will settle matters…. America is now become, or indisputably ere long will be, such a vast, powerful & opulent dominion, that I humbly conceive in order to restore & establish real & substantial harmony affection & confidence … it may be found advisable to settle the line with respect to taxation…. [In short], nothing [exists] but jealousies rancour and ill blood.[4]

After nearly fifteen years as governor, a dejected and hopeless Wright requested leave to return to England.[5] He knew it would be months before Dartmouth’s reply made its way back to Savannah and occupied his time meeting with his Council and cajoling British officials in the hopes that someone – anyone – would provide even modest military assistance. He had learned throughout the years, however, that such requests would likely fall on deaf ears and this time proved no different. “I begin to think,” he wrote in July, “a King’s governor has little or no business here.”[6] South Carolina’s royal Governor Lord William Campbell concurred, declaring in a letter to General Thomas Gage: “All legal government is now at an end,” adding that with just a modicum of support, the backcountry inhabitants would surely flock to the King’s standard.[7] South Carolinian Henry Laurens, who had taken in Wright’s son, Alexander, as an apprentice merchant, noted that the Georgia Assembly “have made [Governor Wright’s] pillow rough.”[8]

The next six months proved increasingly miserable for Wright and Georgia’s Loyalists as the Rebels consolidated their power. They seized control of the provincial militia in July and, a few months later, the courts as well.[9] Moreover, it became an increasingly dangerous time for those who opposed, or even refused to openly support, the Rebels. Loyalists like Savannah River pilot John Hopkins were subjected to daily insults, threats, and physical assaults from the Sons of Liberty. The South Carolina Gazette; and Country Journal reported that on Monday, July 24:

On Monday evening last the town was amused with an exhibition of the new shew. It seems that one John Hopkins has frequently spoken in terms highly reviling the advocates for American Liberty, and the measure they are pursuing; and, although a different conduct has been recommended as eligible, yet he has been persisted in his mischievous declamation, insomuch that he has been lately heard to drink, ” Damnation to America.” This last essay seemed to compleat the man, and to demand some attention from the people. The people therefore, on Monday evening last, waited upon him, and politely requested him to except of a new suit of cloaths; which at first his Modesty rather prompted him to decline; but as they were determined in their generosity, they pressed them upon him, and he was presently and completealy arrayed in the American habit. The more to render this mark of respect from the people public, he was hoisted into a cart, (now a necessary and fashionable carriage in America) and paraded with a crouded retinue through all the squares and streets in town; and the hero of the [day?] was still rendered more conspicuous by a large number of lights which were kept about him for that purpose. The scene lasted about five hours.

Thus, “in consequence of his loyalty to the King,” he wrote in 1784, “he had been barbarously and ill used[,] his estate [had been] confiscated,” and forced to flee to East Florida.[10] Wright described this scene as the “most horrid spectacle I ever saw.”[11] In fact, his own minister, the Reverend Haddon Smith of Christ Church, had been forced to “flee from the violence of the people … [after having] been continually persecuted by the people.”[12] The Reverend had refused the Provincial Congress’ orders to preach a sermon castigating British actions. Wright later testified that the “Rebels persecuted & … hunted him, till he was obliged to fly from the province to avoid the fury of their resentment.”[13] Such lawlessness weighed on Wright who lamented in September that Royal “government [has been] totally annihilated,” leaving him to face daily “the greatest acts of tyranny, oppression, gross insults.”[14]

Thus, it is important to note that Governor Wright, and the Loyalists in general, believed they, and not the Rebels, were beacons of liberty because they defended constitutional government in the face of violent mobocracy.[15] “You may be advocates for liberty,” he cried to the Georgia Assembly, “so am I, but in a constitutional and legal way. You, gentlemen, are Legislators, and let me entreat you to take care how you give a sanction to trample on Law and Government; and be assured it is an indisputable truth, that where there is no law there can be no liberty. It is the due course of law and support of Government which only can insure to you the enjoyment of your lives, your liberty, and your estates; and do not catch at the shadow and lose the substance.”[16] After all, the governor reasoned, how could lovers of liberty excuse the treatment of Augusta’s Thomas Brown? Wright reported in August that the Liberty Boys had “most cruelly treated” and tortured the Augustan.[17] Three months later, Brown described the horrific episode to his father.

People here are under immense pressure to subscribe to a Rebel oath, including me…. [I explained to them] that my situation was particularly delicate [and] that I did not wish to take up arms against that country which gave me being. On the other hand, it would be equally disagreeable to me to fight against those amongst whom, it was probable, I should spend the remainder of my days. Additionally, I told them I desired to live in peace and tranquility without meddling with politics.

The Rebels had no patience for neutrality and, after a short scuffle, fractured Brown’s skull with the butt of a rifle. The “cowardly miscreant[s]” then carried him off and tortured him “with unparalleled barbarity,” by tying him to a tree and lighting a fire under his feet.[18]

The days of mid-to-late 1775 were painfully confused and contingent. Oftentimes both Tory and Whig believed themselves to be losing ground in the battle for hearts and minds. As Wright mourned the loss of his authority, certain Rebels bemoaned the lack of revolutionary zeal in their own ranks. A full month after he announced the virtual dissolution of his government, Provincial Congress member Peter Taarling confided to John Houstoun, one of Georgia’s delegates to the Continental Congress: “I wish it was in my power to give you a reciprocal acc’t of the warlike spirit of Georgia . . . [instead] I’ll therefore leave it and begin to hope, perhaps a few months more, may rouse us and we will be more used to drums & politicks, than what we are at present.”[19]

In December, just two months after Taarling penned his frustrated letter to Houstoun, Wright learned that the King had indeed approved his request for leave. The governor informed Lord Dartmouth, Secretary of State for the American Colonies, that “all the King’s officers and friends to government write for my continuance amongst them … [and] I am well informed and have been told by several of the Liberty people that they [also] express great concern and uneasiness at my intention of leaving the province at present.”[20]

During the first week of January 1776, Wright reassured Dartmouth substantial “numbers would join the King’s standard” if the ministry provided “proper support.” Instead, however, we have been left with “no troops, no money, no orders, or instructions.” Couple this deplorable state of affairs with “a wild magnitude [of Liberty people] gathering fast [and] what can any man do in such a situation?”[21] Wright added that it was doubly shameful that “His Majesty’s officers and dutiful & loyal subjects [should] be suffered to remain under such cruel tyranny and oppression.”[22]

Governor Wright would soon learn the lengths to which the Rebels would go to exercise their tyranny when the twenty-four year-old son of his best friend, the late James Habersham, volunteered to apprehend the governor and his council. During the evening of January 18, Major Joseph Habersham and a small hand-picked party made their way through the chilly darkness with ominous orders in hand and made the one-half mile jaunt from Tondee’s Tavern to the Governor’s mansion.[23]

At the very moment the rebel Council resolved to cross the Rubicon, thus ensuring the ruination of nearly two decades of Wright’s inexhaustible work and dreams, the governor welcomed dinner guests at the Executive Mansion (on the site of the modern Telfair Academy) on St. James’s Square (modern Telfair Square).[24] This was no ordinary dinner party, however; in fact it was no party at all. Instead, it was a meeting of Georgia’s highest-ranking ministerial officials and the discussion focused on the town’s ever-growing mobocracy. Moreover, the conversation must have centered on the extremely limited range of options available to them.

As they labored through a difficult meal at Wright’s mahogany dining table under the comforting gaze from a portrait of King George II, a sudden noise at the front door halted the conversation.[25] Seemingly out of nowhere, Habersham’s posse descended upon the mansion and rushed past the guard placed at the entrance.[26] Major Habersham entered the dining room amidst a cacophony of loud voices, boots on wood, and confusion and, with apparent grace and dignity, bowed to the assembled guests, and marched to the head of the table. Placing his arm on Governor Wright’s shoulder, he stunned the dinner party, declaring, “Sir James, you are my prisoner.” Without waiting for Habersham to complete his thought, most of Wright’s dinner guests scattered for the exits. The capture of the governor proved to be the final motivation for many Loyalists, who made haste for St. Augustine. One such emigrant, Martin Jollie, confided to East Florida’s royal Governor Patrick Tonyn that “these deluded people has made every prudent thinking man withdraw from the party.”[27] In May 1785, Wright provided testimony for Jollie’s claim, stating: “I conceive him to be a person worthy of the humanity & assistance of Government.”[28]

The Council of Safety reconvened a few hours later and resolved that each of those arrested be permitted to return “to their respective homes upon their parole assuring that they will attend his Excellency the Governor’s house, at nine o’clock to-morrow morning.” The Council confined Wright to his home under the watchful eye of an armed guard for a few days prior to granting him parole upon the conditions that he remain in his home and not correspond “with any of the officers or others on board the ships of war now at Tybee [Island], without the permission of this Board.”[29] The denial of Wright’s personal liberty, in the name of liberty, prompted at least one member of Georgia’s Provincial Congress to renounce his own oath to the Rebels.[30]

The deeply personal nature of the rapidly unfolding civil war that erupted in Georgia made Wright’s parole a precarious and dubious condition. In fact, Rebel officer William Moultrie acknowledged: “what was called a ‘Georgia parole’ and to be shot down were synonymous.”[31] Exacerbating Wright’s situation, the Council of Safety issued a resolution requiring parolees like Wright and his Council members be relocated to the backcountry upon the entry of British vessels up the Savannah River.[32] Worse yet, royal Chief Justice Anthony Stokes wrote of a Rebel plan to forcibly draft Loyalists into the militia and use them as cannon fodder should the British invade.[33] Just days after Wright and his cohorts received their paroles, royal Lieutenant Governor John Graham privately learned that the Rebels “determined to confine [him], upon which [he] was obliged to conceal himself night and day in Swamps for a considerable time, exposed to all the inclemencies of the weather, until he fortunately made his escape on board the King’s ships.”[34]

Such actions and rumors led Wright to believe the Rebels had broken, or planned to break, the terms of his parole and the promised safety of parole seemed more dubious with each passing day. Rabble-rousers continually harassed him and his family and, on more than one occasion, subjected his home to scattered musket shots.[35] Wright’s Loyalist claim and extant correspondence are mute on the subject of shots being fired into the governor’s mansion and such behavior would have been a violation of a resolution passed by the Rebel Council on January 16, which forbade the Georgians from “idly fir[ing] a gun in the town.”[36] But irrefutable proof exists that he was harassed and feared for the safety of himself and his family.[37] In the face of innumerable insults and threats, Wright bemoaned that he could avail himself of “not the least means of protection, support, or even personal safety,” which was far “too much” to endure.[38] Additionally, Josiah Tattnall claimed that Wright’s parole contained a caveat allowing him to “quit the country” should he be insulted, which he had been.[39]

These combined factors compelled him to seek the security and emotional comfort of the British vessels then in the harbor. Provincial (royal) Councilmen Josiah Tattnall and John Mulryne then provided Governor Wright with a “boat and men” to effect his late night escape from his home.[40] In a letter to Lord George Germain, the Secretary of State for the American Department, he wrote: “in order to avoid the rage and violence of the Rebels …, [I] was reduced to the necessity of leaving the town of Savannah in the night.”[41] He arrived safely aboard the H.M.S. Scarborough at Cockspur Island at 3 in the morning of February 12. Captain Andrew Barkley announced the joyous news of Wright’s arrival with a thunderous fifteen-gun salute.[42]

Although the Scarborough secured the personal safety for the governor and his family, the ship was unable to save many of his personal affects (which may explain why there is so little extant personal correspondence) when the Rebels destroyed a British vessel containing his baggage in the Savannah River.[43] The Provincial Congress, however, proffered no such justification, tersely noting: “Governor Wright observed his parole of honor for a time, but after nearly four weeks of confinement broke it, and, escaping through a back door of his house, fled in the night time and made his way, under cover of darkness, to an armed British ship anchored in the harbor.”[44]

Thus it was for Georgia’s most popular and successful colonial governor, whose efforts doubled the colony’s boundaries and enriched many a parvenu – patriotism to King and Crown clearly had a steep price tag and no one paid a higher price than the governor himself. Although Wright would return to Savannah in 1779 in a modestly successful attempt to restore British rule, he left the province for good in the summer of 1782 following the British evacuation. He occupied his final few years seeking recompense for Georgia’s Loyalists. The Loyalist Commission accepted his claim of £100,260.11 as valid and awarded him £35,347. A subsequent Parliamentary act provided a further reduction of all claims in excess of £10,000 and Wright’s ultimate award amounted to £32,977 plus £1,000 per annum as a pension for his service as governor. According to Robert Mitchell’s examination of Georgia Loyalist claims, Wright’s individual claim represented eleven percent of all Georgia claims and his award nearly equaled fifteen percent of all compensation.[45]

Wright, however, would not live to hear the committee’s final decision. He died at his home on Fludyer Street in southeast London on Sunday, November 20, 1785 and was interred in the North transcept at Westminster Abbey one week later. His death was reported on both sides of the Atlantic. The most thorough of these was the Morning Chronicle and London Advertiser:

… As he presided in [Georgia] for two and twenty years with distinguished ability and integrity, it seems to be a tribute justly due to his merit as a faithful servant of his king and Country. Before the commotions in America, his example of industry and skill in the cultivation and improvement of Georgia was of eminent advantage; and the faithful discharge of his executive and judicial commission was universally acknowledged, by the people over whom he presided, none of his decrees as Chancellor having ever been reversed. Under all the difficulties which attended the latter period of his government, his spirited conduct in defence of that province was singularly manifested. His loss is deeply felt and sincerely lamented by his family and friends, as well, as by his unfortunate fellow-sufferers from America, whose cause he most assiduously labored to support and solicit; and the success which attended his active exertions in their behalf afforded him real comfort under his languishing state of health for some time before his death.[46]

The Gazette of the State of Georgia was much less effusive, simply stating: “Died. Yesterday at his house in Westminster, Sir James Wright, Bart., many years Governor of Georgia.”[47] Alas, after having dedicated more than two decades of his life to the province of Georgia, overseeing rapid economic and growth and geographic expansion, James Wright’s life was reduced to a hollow afterthought.

[1] Thursday, January 18, 1776, in Mary Bondurant Warren and Jack M. Jones, eds., Georgia Governor and Council Journals, 1774-1777 (Athens, GA: Heritage Papers, 2006), 153.

[3] “At a special meeting of the Council of Safety, Jan. 18th, 1776, p.m.,” in Allen D. Candler, et. al., Colonial Records of the State of Georgia (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1904-1916 and 1976-1989), 1:101. For reasonably detailed and similar examinations of the arrest of Wright see, Robert G. Mitchell, “Loyalist Georgia” (PhD diss., Tulane University, 1965), 35, 38, 46, 56, and 64-72; Charles Risher, “Propaganda, Dissension, and Defeat: Loyalist Sentiment in Georgia, 1763-1783” (PhD diss., Mississippi State University, 1976), 110-117; W. W. Abbot, The Royal Governors of Georgia, 1754-1775 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1959); Kenneth Coleman, The American Revolution in Georgia, 1763-1789 (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1958); Allen D. Candler, ed., The Revolutionary Records of Georgia (Atlanta: Franklin-Turner Company, 1908), 1:101-108. See also, James Wright Loyalist Claim, National Archives, Kew, England, Colonial Office, 5/657; John Graham Loyalist Claim, National Archives, Kew, England, American Office, 12/4; and Anthony Stokes Loyalist Claim, National Archives, Colonial Office, 5/657; and Josiah Tattnall, Loyalist Claim, National Archives, American Office, 12/4. Mary Bondurant Warren has provided many of the Loyalist Claim transcriptions, either complete or partial.

[4] Wright to Dartmouth, August 24, 1774, in National Archives, Colonial Office, 5/663; For a general overview of the loss of royal power in Georgia see, Coleman, American Revolution in Georgia, chapters 3-4.

[5] Wright to Dartmouth, June 17, 1775, in Collections of the Georgia Historical Society (Savannah: Georgia Historical Society, 1840-1989), 3:183-185. See also, Wright to Dartmouth, November 1, 1775, in Collections, 3:218-220 and Wright to Dartmouth, December 11, 1775, in Collections, 3:226-227. It was in this last letter that Wright learned that the King had granted his request.

[6] James Wright to Lord Dartmouth, July 10, 1775, in Collections, 3:195.

[7] William Campbell to Thomas Gage, July 29, 1775, in Gage Papers, American Series, Clements Library, University of Michigan.

[8] For Laurens’s work with Alexander Wright see, Henry Laurens to James Wright, August 7, 1768, in David R. Chesnutt, et al., The Papers of Henry Laurens (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 1968-2002), 6:51-54. For Laurens’s comment regarding Wright and the Assembly see, Henry Laurens to John Laurens, May 3, 1774, in Papers of Henry Laurens, 9:422-425.

[9] See Wright to the Earl of Dartmouth, September 16, 1775, in Peter Force, American Archives (Washington, DC: M. St. Clair, Clarke and Peter Force, 1837-1853), 11:114; Wright to Dartmouth, October 14, 1775, in Collections, 3:215-217; and Wright to Dartmouth, December 9, 1775, in Collections, 3:223-225. For an excellent analysis of Georgia’s final descent into the Rebel camp, see Abbot, Royal Governors of Georgia, chapter 8. Concerning the militia see, for example, Thomas Netherclift to James Wright, August 19, 1775, Collections, 10:44-45 and James Robertson to James Wright, August 14, 1775, in Collections, 10:45-46.

[10] John Hopkins Loyalist Claim, National Archives, American Office 13/96. A photocopy of this claim is available at the Georgia Historical Society, Savannah, Georgia (John Hopkins loyalist claim, MS 1477). For an unsympathetic recounting see, Hugh McCall, History of Georgia (Atlanta: A. B. Caldwell, 1909), 2:288.

[12] “Proceedings,” July 17, 1775, in American Archives, 2:1554-1555 and “Memorial of Hadden Smith,” July 22, 1775, in Edward Cashin, ed., Setting out to Begin a New World: Colonial Georgia, A Documentary History (Savannah: The Beehive Press, 1995), 158-159.

[16] Governor Wright’s Speech to the General Assembly, January 18, 1775 in American Archives, 1:1152-1153.

[18] Thomas Brown Loyalist Claim, National Archives, American Office, 13/34; Thomas Brown to Jonas Brown, November 10, 1775, in Cashin, ed., Setting out to Begin a New World, 160-164; and Cashin, The King’s Ranger: Thomas Brown and the American Revolution on the Southern Frontier (New York: Fordham University Press, 1999), 27-29.

[19] Peter Taarling to John Houstoun, October 24, 1775, in Georgia Historical Society, John Houstoun Papers, MS 397. Taarling was a delegate to the Georgia Provincial Congress from St. Andrew’s Parish.

[21] Wright to Dartmouth, January 3, 1776, in National Archives, Colonial Office, 5/665. See also, Wright to Dartmouth, November 16, 1775, in National Archives, Colonial Office, 5/665 and Wright to Dartmouth, December 19, 1775, in Collections, 3:228.

[23] “At a special meeting of the Council of Safety,” January 18, 1776, p.m., in Collections, 5.1:38. See also, RRG, 1:101.

[24] For a contemporary street and building map of Savannah see, Paul Pressly, On the Rim of the Caribbean: Colonial Georgia and the British Atlantic World (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2013), xiii.

[25] For further details concerning Wright’s property, see Sir James Wright’s Loyalist Claim, National Archives, American Office, 13/85. In the 107-page typed transcript of his claim, Wright does not mention his arrest, only that, “in Feb. 1776 I was under the necessity of retiring & went on board His Majesty’s ship Scarborough.” This is a reference to his escape under cover of darkness.

[26] “At a special meeting of the Council of Safety, Jan. 18th, at 11 o’clock at night, 1776,” in RRG, 1:102. See also, Charles Colcock Jones, The History of Georgia (Boston: Houghton, Mifflin, and Company, 1911), 2:211-212.

[27] Martin Jollie to Patrick Tonyn, February 13, 1776, quoted in Robert G. Mitchell, “Loyalist Georgia” (PhD diss., Tulane University, 1964), 65.

[29] “At a meeting of the Council of Safety, Jan. 19th, 1776,” in Candler, Revolutionary Records of Georgia, 1:103-104.

[30] Basil Cowper Loyalist Claim, National Archives, American Office, 12/4. Cowper claims “he continued with [the Rebels] till the Governor and Council were made prisoners when he quitted them.”

[32] “At a meeting of the Council of Safety, Jan. 19th, 1776,” in Candler, Revolutionary Records of Georgia, 1:103-104.

[33] Anthony Stokes, Desultory Observations, on the Situation, Extent, Climate, Population, Manners, Customs, Commerce, Constitution, Government, Religion, &c. of Great Britain (London: J. Davidson, 1792), 26.

[36] “At a Council of Safety at Mrs. Tondee’s, January 16th, 1776,” in Candler, Revolutionary Records of Georgia, 1:98-100.

[37] The veracity of the account concerning shots fired into Wright’s home cannot be conclusively affirmed or refuted. He did not mention such an episode in either his Loyalist claim or in any extant correspondence. However, Josiah Tattnall mentioned in his claim that Wright had been continually harassed and “insulted.” See, Josiah Tattnall, Loyalist Claim, National Archives, American Office, 12/4. Historians Stevens and Jones have produced thoroughly researched and generally trustworthy histories of Georgia.

[41] Wright to Germain, February 12, 1776, in James Wright, Loyalist Claim, TNA, CO 5/657. See also, Coleman, American Revolution in, 68-69; Coleman, “James Wright,” in Georgians in Profile: Essays in honor of Ellis Merton Coulter, ed. by Horace Montgomery (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1958), 54. Wright made his escape on February 11, 1776. For his explanation of breaking parole see, Wright to His Council, February 18, 1776, in Ronald G. Killian and Charles T. Waller, eds., Georgia and the Revolution (Atlanta: Cherokee Publishing Company, 1975), 162-163.

[42] “Captain’s Log, H.M.S. Scarborough, February 10, 1776, National Archives, Kew, England, Admiralty Office Papers, 51/867.

[43] Middlesex Journal and Evening Advertiser, May 21-23, 1776. This published extract from a letter from Kirkwell, in Orkney, dated May 4, noted that Wright arrived at that place with his secretary and “domesticks.” The St. James’s Chronicle or the British Evening Post, of May 21-23, 1776, mentioned that Wright was in Boston prior to his arrival in Kirkwell.

[45] Mitchell, “The Losses and Compensation of Georgia Loyalists,” 239-240. See also, David Wilmot, Historical View of the Commission for Enquiring into the Losses, Services, and Claims of the American Loyalists, at the Close of the War Between Great Britain and Her Colonies in 1783 (London: J. Nichols, Son, and Bentley, 1815), 47.

12 Comments

Wright’s obituary in the Morning Chronicle and London Advertiser has a precious tidbit: only a few years after Yorktown, someone in London was content to refer to the Revolution as “. . . the commotions in America . . .”

Good point, Rick.

Tattnal’s claim that Wright’s parole contained a clause allowing him to break his word if he had been ‘insulted’ seems a bit lax. Wouldn’t such a clause referenced at that point in time require the ‘insult’ be a physical injury or assault of some sort? It seems to me that Wright’s excuse for breaking parole was a bit thin. Later in the southern campaigns, Patriots in similar circumstance tended to face hanging at the hands of British officers.

It’s a valid point, Wayne, but such a caveat is mentioned in at least a handful of Loyalist claims Although I readily acknowledge the political leanings of these Loyalists, I just as readily acknowledge the leanings of their opponents and thus must interpret things accordingly. Interestingly, the Rebels tried to get their hands on their ‘escapee’ during the siege of Savannah in 1779.

Thanks Dr. Brooking, on the subject of paroles, I have been looking into the summer campaign of 1780 in South Carolina and Georgia. Clinton gave a very favorable parole to all the backcountry people in early June that caused Cornwallis a good deal of grief. Just as the general left Camden and tried to spend a pleasant summer in Charleston, Rawdon broke the news. “The proclamation strikes home at us now, for these frontier districts, who were before secured under the bond of paroles, are now at liberty to take any steps which a turn of fortune might advise.” Over the following couple of weeks, Sumter recruited an army from those very districts. Within six weeks, Cornwallis complained to Clinton that, “The whole country between Peedee and Santee has ever since been in an absolute state of rebellion.”

What a difference a well worded parole makes. 🙂

Very true, Wayne!

A very minor point – Wright’s Fludyer Street is not the current Fludyer Street in SE London. His Fludyer Street was in Westminster, and no longer exists. It sat roughly where the Foreign Office is now, which was built in the mid/late 19th century. I haven’t looked at late 18th century maps of London but I’d imagine where the current Fludyer Street is would have practically been country real estate at the time.

Thanks for the reply, Dan. I was fairly certain that I’d looked at an 18th century map because I knew the old Fludyer Street was no more. I’ll double check and get back to you.

Hi Dan, Fludyer Street was located “between King Street, Westminster, and St. James’s Park (H. B. Wheatley and P. Cunningham, London Past and Present, 66).

Greg: Thanks for the excellent article. I did not realize that Georgia Whigs were so organized and aggressive this early in the conflict. It is interesting to see what happened to the royal governors after Lexington and Concord, and Bunker Hill. Most wound up on British warships, it seems. (Connecticut and Rhode Island did not have royal governors). Christian

Thanks, Christian.

Great article, Greg. I would like to point out one minor detail. Savannah at this times consisted of only six squares. Tondee’s Tavern was only a block away from the Governor’s residence. Literally around the corner and maybe 200 yards as the crow flies. Nowhere near a half-mile away.

Tim