Go to any Revolutionary War period living history program or reenactment and you hear it again and again. “Huzzah for Great Washington and the Continental Congress!” “Huzzah for good King George and Parliament!” Huzzah this and Huzzah that all day.

If our forefathers could come back to one of these events, they would be mightily puzzled. “What is this ”huzzah ?” they might say. “When we cheered, it was Huzzay.”

Huzzay? Yes. Not Huzzah.

In the English speaking world from the late sixteenth century to the mid nineteenth century, the dominant cheer was Huzza! (spelled Huzza, not Huzzah or Huzzay).[1] During the period of the American War for Independence Huzza! appears so frequently, and to the exclusion of other cheers, in letters, diaries, newspaper articles, orders and literature as to make it the predominant, if not universal cheer on both sides of the Atlantic.

It is always tricky to attempt to replicate the pronunciation of words as they were pronounced centuries ago. A cheer is a vocalization. Accents, inflections and pronunciations constantly evolve. In the absence of direct evidence from audio recordings, ancient pronunciations can be questioned. And the eighteenth century spelling, “Huzza,” is ambiguous regarding pronunciation. There are at least forty different ways in which the word “Huzza” might be pronounced in the English language.[2] Which of these forty-plus possible pronunciations was in use in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries?

In the case of “Huzza!” there is compelling evidence from period dictionaries, poetry and song that the common, indeed virtually universal pronunciation among English speakers was “Huzzay!” to rhyme with words such as “hay,” “day,” “pray,” “say,” “may,” “away,” “delay” and “play.”

Dictionary Evidence

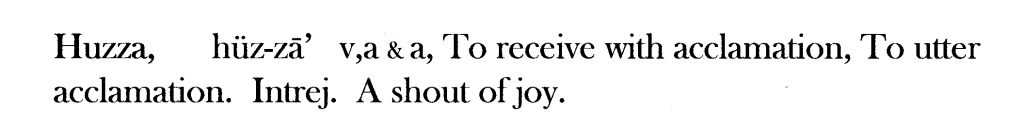

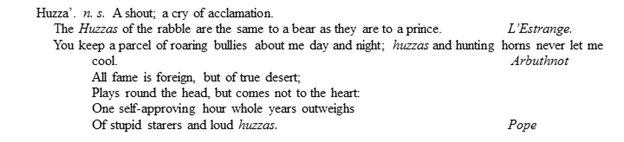

The obvious first place to go for pronunciation guidance is dictionaries. Thirty-eight dictionaries published between 1702 and 1994 were consulted during the course of this study.[3] Seventeen of those dictionaries were published between 1702 and 1806 by fourteen different lexicographers.[4] Each of those fourteen eighteenth and early nineteenth century lexicographers included “Huzza” and defined it as a cheer, a shout , a cry of acclamation. All spelled it the same way — “Huzza.” All those who included accent marks indicated that the stress was to be placed on the second syllable.

Seven of those lexicographers also indicated pronunciation, six by pronunciation guides, one by citing a passage from poetry.[5] All gave the pronunciation of “Huzza” as Huzzay. Space limitations make it impractical to reproduce all of the word entries and pronouncing guides here. The following abridged examples illustrate the ways in which eighteenth century lexicographers indicated the proper pronunciation of “Huzza.”

SHERIDAN, Thomas. A Complete Dictionary of the English Language, both with Regard to Sound and Meaning[6]

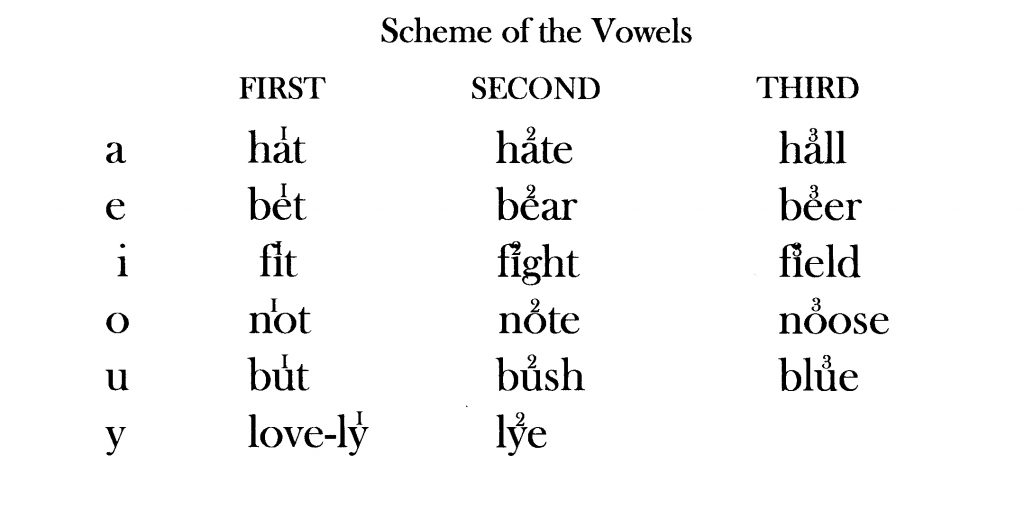

The 1789 edition of Thomas Sheridan’s dictionary (first published in 1752) contains a “Scheme of the Vowels” with which he indicates the proper pronunciation of words using superscript numbers. Here is his entry for Huzza and his “Scheme of the Vowels.”

Sheridan indicates that the “u” in Huzza is the short version to be pronounced to rhyme with “but,” and that the “a” in Huzza is the long version to be pronounced to rhyme with “hate,” i.e. “Huzzay!”

ALEXANDER, Caleb. The Columbian Dictionary of the English Language[7]

Caleb Alexander’s dictionary, published in Boston in 1800 gives the following definition for Huzza and “Scheme of the Vowels.”

Although Alexander employs a different notation, the indicated pronunciation is the same: the “u” pronounced as in “but,” and “a” as in “bate.” — “Huzzay!” — this time in an American dictionary.

WALKER, John. A Critical Pronouncing Dictionary and Exposition of the English Language[8]

The 1802 edition of John Walker’s dictionary (first published in 1798) gives the following definition of “Huzza” and pronunciation guide.

The numbers in parentheses following the entries refer to a long series of notes elaborating on the rules of pronunciation. The following are pertinent to this discussion.

Here again the proper pronunciation of Huzza is given as Huzzay.

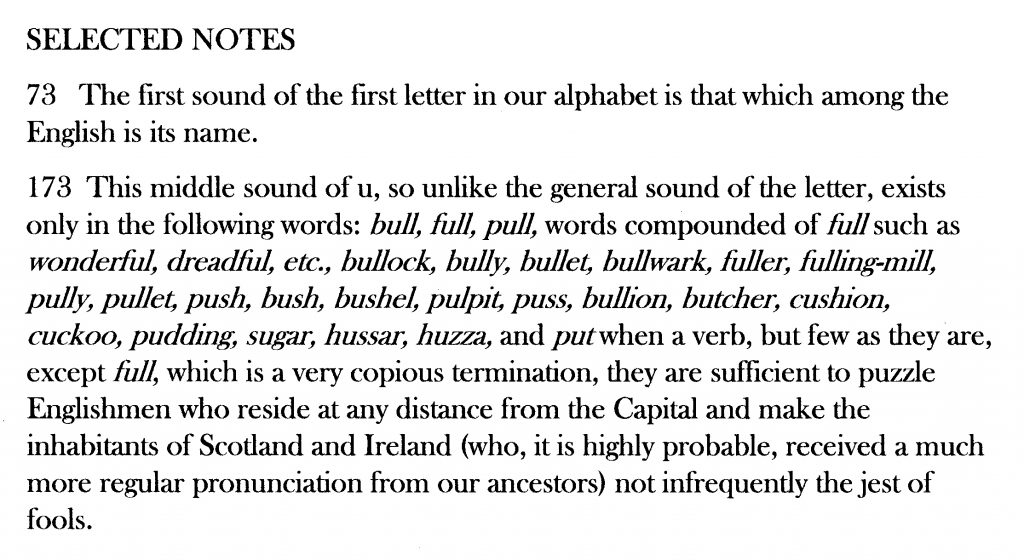

JOHNSON, Samuel. A Dictionary of the English Language[9]

Samuel Johnson used literary citations to illustrate both meaning and pronunciation. The following is the entry from the 1755 edition of his famous dictionary.

The Pope citation is from Alexander Pope’s “Essay on Man,”[10] which consists of four “epistles” in rhyming couplets of 250 to 350 lines each. The passage quoted by Johnson indicates that Huzzas is to rhyme with outweighs. Subsequent editions of Johnson’s Dictionary published in England and in America confirm that “Huzzay” was still the prescribed pronunciation on both sides of the Atlantic well into the first quarter of the nineteenth century.[11]

Although the means differed, all seven eighteenth century lexicographers who indicated the way in which words were to be pronounced specified the same pronunciation of Huzza — “huz-ZAY,” to rhyme with day, say, way, hay, etc.

As a check to determine whether the indicated 18th century pronunciation was the same as modern pronunciation, several modern dictionaries were consulted.[12] A sampling of words currently pronounced with the long A as in “day” and “play,” and the pronunciation guides in those dictionaries confirmed that the indicated eighteenth century pronunciations and current pronunciations are the same.

But dictionary definitions and their pronunciation guides are prescriptive rather than descriptive.

They set forth what men of letters held to be proper usage and pronunciation. Was this the pronunciation that was actually used by common people in the streets and soldiers in the field?

Evidence from Poetry and Song

One of the most popular forms of entertainment in the eighteenth century was the theater. Men and women of all classes from the highest to the lowest patronized the theater. One of the most popular actors and playwrights of the period was David Garrick. In 1761 or 1762 he wrote a short “afterpiece” or interlude entitled “The Farmer’s Return from London.”[13] It is written in rhyming couplets reminiscent of a Dr. Seuss story. Every pair of lines ends with a clear rhyme, including these:

WIFE:

But was’t thou at court, John? What there has thou seen?

FARMER:

I saw ‘em, heaven bless ‘em! You know who I mean.

I heard their healths prayed for agen and agen,

With proviso that one may be sick now and then.

Some looks speak their hearts, as it were with a tongue.

Oh, Dame! I’ll be damned if they e’er do us wrong:

Here’s to ‘em, bless ‘em boath. Do you take the jug.

Would’t do their hearts good, I’d swallow the mug. (Drinks)

(To Dick) Come, pledge me, my boy.

Hold, lad; hast nothing to say?

DICK:

Here, Daddy, here’s to’em! (Drinks)

FARMER:

Well said, Dick, boy!

DICK:

Huzza! (emphasis added)

Clearly Garrick intended that “Huzza” should be pronounced “Huzzay,” to rhyme with “say.” Any other pronunciation would have been jarringly out of place and made that single line the only line in the entire piece that did not rhyme. And just as clearly, his audiences, composed of high, middling and lower class patrons expected to hear “Huzza” pronounced “Huzzay.”

An earlier example of the use of “Huzza” is the ballad in couplets “English Courage Display’d, or Brave News from Admiral Vernon,” attributed to “a seaman on board the Buford, the Admiral’s ship, and sent from Jamaica.”[14] It was published as a broadside in England about May of 1741. The pertinent passage reads:

While trumpets they did loudly sound and colours were displaying,

The prizes he with him brought away while sailors were Huzzaing.

Here we have an example of a common seaman rhyming “Huzzaing” with “displaying.”

In a poem titled An Ode to Peace, by an anonymous author styling himself “Crito,” in The General Magazine of Newcastle on Tyne for October, 1748[15] Huzzas, is rhymed with ways.

While we wait thy warm Caresses

Urge us on in loyal Ways

Not in formal trite Addresses,

Not in Riot and Huzzas.

In the song “American Freedom,” published in 1775,[16] Huzza is rhymed with away and delay.

Hark! ‘tis Freedom that calls, come Patriots awake;

To arms my brave Boys and away;

‘Tis Honour, ‘tis Virtue, ‘tis Liberty calls,

And upbraids the too tedious Delay.

What Pleasure we find in pursuing our foes.

Thro’ Blood and thro’ Carnage we’ll fly;

Then follow, we’ll soon overtake them, Huzza!

About February, 1779, following the acquittal of Admiral Keppel, the song “Keppel Forever”[17] was published. It contains the following lines in which Huzza is rhymed with play.

Bonfires, bells did ring; Keppel was all the ding,

Music did play;

Windows with candles in, for all to honor him:

People aloud did sing, “Keppel! Huzza!”

Another example is in a song that appeared on an engraved song sheet published about 1780[18] titled “The Drum,” in which Huzza is rhymed with away.

Now over the bottle, our valor we boast,

While the drum, hark the drum, hark the drum rolls every toast.

For America now, Huzza!

The work’s ne’er done, we’ll dance, sing, and play,

And the drum we’ll unbrace, and the drum we’ll unbrace,

Till a war again calls away.

In a song honoring Washington’s Birthday, published in 1784,[19]Huzza is rhymed with day.

Fill the glass to the brink,

Washington’s health we’ll drink,

‘Tis his birth-day.

Glorious deeds he has done,

By him our cause was won,

Long live great Washington,

Huzza! Huzza!

In the song titled simply “A Song,” published in 1787,[20] Huzza is rhymed with obey and sway.

Thus no longer with stocks and pillories vex’d

Nor with work, jail or sheriff perplex’d, perplex’d,

The mobmen shall rule, and the great men obey,

The world upon wheels shall be all set agog

And blockheads and knaves hail the reign of King Log;

Under his sway,

Shall Tag, Rag, and Bobtail,

Lead up our decorum, Huzza!

In “The Echoing Horn,” published in 1798,[21] we have Huzza rhymed with delay.

The morning is up and the cry of the hounds,

Upbraids out too tedious delay.

What pleasure we feel in pursuing the fox!

O’er hill and o’er valley he flies;

Then follow, we’ll soon overtake him; Huzza!

Later in this same song Huzza is also rhymed with gay and day.

An early nineteenth century ballad celebrating Nelson’s victory in the Battle of Copenhagen[22] rhymes Huzza with fray.

Three cheers of all the fleet

Sung Huzza!

Then from the center, rear, and van,

Every captain, every man,

With lion’s heart began

To the fray.

The 29 December, 1812 victory of the USS Constitution over HMS Java was celebrated in “Glorious Naval Victory”[23] by James Campbell, “A Boatswain’s Mate on Board the Constitution.” It was published as a broadside upon the Constitution’s return to Boston in 1813, and rhymes Huzza with away.

It was at two o’clock the bloody fray begun,

Each hardy tar and son of mars was active at his gun,

Until their fore and mizzen-mast was fairly shot away,

And with redoubled courage, we gave them three Huzzas.

Even as late as 1840, we hear Huzza rhymed with away[24] in England in this tribute to Napier’s victory over the Egyptians.

Hear what has happened lately along the Syrian coast:

The downfall of the Egyptians, of which we made our boast.

So here’s a health to brave Napier, to brave Napier Huzza!

Who conquered the Egyptians and made them run away.

These are just a few of the many examples in rhyming poetry and song of the period in which the accepted pronunciation of Huzza in indicated.

The evidence is compelling that the preferred and virtually universally accepted pronunciation of Huzza among lexicographers, poets and song writers, both the educated and the less educated classes, in America and in England in the mid-to-late eighteenth century and well into the nineteenth century was Huzzay.[25]

So where does Huzzah come from?

Credit (or blame, depending on one’s point of view) for changing Huzzay to Huzzah belongs to Noah Webster.

Webster (1758-1843) was one of the most influential men of his period. A tireless writer, teacher and advocate for American values, he was an ardent Anglophobe. He is known principally for his “Blue Backed Speller” (first published in 1783, it was the standard American spelling book until the late nineteenth century), his Dictionaries and for pushing strong copyright laws through Congress.

Webster strongly advocated the use of “American” words, spellings and pronunciations rather than “English” ones. In the case of Huzza, the evolution of this advocacy can be traced through successive editions of his dictionaries.

The earliest version of Webster’s dictionary[26] defines Huzza conventionally as “A shout of joy or triumph,” and indicates the pronunciation to be Huzzay.

In the next edition, first published in 1828[27] Webster defined Huzza thusly:

HUZ-Z`A, n. A shout of joy. A foreign word used in writing only, and most preposterously, as it is never used in practice. The word used is our native word hoora or hooraw. [See Hoora.]

HUZ-Z`A, v.i. To utter a loud shout of joy or an acclamation in joy or praise.

HUZ-Z`A, v.t. To receive or attend with shouts of joy.

HURRAW exclam. Hoora; Huzza [see Horra.]

HURRAH

HOOR`A exclam. [Sw. hurra. The Welsh has swara, play, sport,

HOORAW’ but the Swedish appears to be the English word.]

A shout of joy or exultation. [This is the genuine English word, for which we find in books most absurdly written Huzza, a foreign word never or rarely used.]

This edition is the first that gives the pronunciation of Huzza as Huzzah, with the final “a” to rhyme with “bar,” “father “and “ask.”

As the years progressed, Webster got terser and more direct. In the 1848[28] edition of his dictionary the entry for Huzza was simply:

H ÛZ-ZÄ‘, n. A shout of joy. See Hurrah.

By 1860[29] his definition of Huzza was:

HUZ-ZÄ’, n. A shout of joy. The word chiefly is our native word, HURRAH, which see.

Subsequently Huzza disappears from Webster’s dictionaries.[30]

Of course, Webster’s position was not immediately or universally adopted. Other dictionaries, many based on Walker’s definitions and pronunciations continued to include Huzza pronounced Huzzay. One of the latest of these was the Palmetto Dictionary,[31] published in 1864 in Richmond, Virginia. It includes Huzza with Walker’s Huzzay pronunciation, and does not include any of Webster’s variations such as Hurrah, Hooray, Huzzah, etc.

Then two decisive events took place.

- The North won the Civil War rendering things northern, such as Webster’s Dictionary, dominant in American society.Dictionary was reprinted in England and quickly supplanted dictionaries based on Johnson, Walker and other earlier lexicographers.

- Webster’s Dictionary was reprinted in England and quickly supplanted dictionaries based on Johnson, Walker and other earlier lexicographers.

Webster had triumphed. Huzza (along with a number of other words) disappeared from common usage while some 70,000 other words were added to the English lexicon.

Today Huzza is remembered as the dominant cheer of the eighteenth century only by students of history. For everyone else it is an “…archaic variant of Hurrah.”[32]

_______________

I am indebted to Ronald W. Poppe, Hardy Menagh and Mark Hilliard, members of The Brigade of the American Revolution, each of whom generously contributed examples from their personal research illustrating the pronunciation and use of Huzza in the eighteenth century.

[FEATURED IMAGE AT TOP: “A New Method of Macarony Making, as practised at Boston in North America.” Source: Library of Congress and British Library]

[1] The Oxford Dictionary of the English Language, (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1933). The entry for HUZZA includes 14 quotations from literature dating from 1560 to 1880 in which the word Huzza appears as a cheer.

[2] Period and modern lexicographers give at least four different ways to pronounce the “U” and at least five different ways to pronounce the letter “A.” Adding to that whether the stress is placed on the first or the second syllable yields over forty possible combinations.

[3] The authors (lexicographers) and publication dates of the dictionaries consulted are listed below in alphabetical order; those marked with an asterisk (*) were published between 1702 and 1806:

*Alexander, Caleb (1800)

*Ash, John (1775)

*Bailey, Nathan (1755 & 1786)

*Barclay, James (1799)

*Cocker, Edward (1724)

*Dyche, Thomas (1765)

*Entick, John (1783)

*Fenning, Daniel (1775)

* “J. K.” (1702)

*Johnson, Samuel (1755, 1813, 1818)

Merriam-Webster’s Collegiate Dictionary 10th ed. (1994)

*Perry, William (1788, 1800)

*Sheridan, Thomas (1789)

The Oxford English Dictionary (1961)

The Palmetto Dictionary (1864)

Todd’s, Johnson’s and Walker’s Pronouncing Dictionary (1858)

*Walker, John (1798, 1802, 1824, 1829)

*Webster, Noah (1806)

Webster, Noah (1807, 1817,1828, 1833, 1848, 1849, 1860, 1867)

Webster’s New World Dictionary, Third College Edition (1984)

Worcester, Joseph E. (1860)

Wright, Joseph (1905)

Wright, Thomas (1880)

Wyld & Partridge (1867)

[4] The fourteen authors (lexicographers) and publication dates of the seventeen dictionaries published between 1702 and 1806 are denoted with an asterisk (*) in the list above (Note 3).

[5] The seven dictionaries that indicate pronunciation are:

Caleb Alexander, The Columbian Dictionary of the English Language, (Boston: Thomas & Andrews, 1800).

Daniel Fenning, The Royal English Dictionary, or a Treasury of the English Language, (London: L. Hawes, 1775).

Samuel Johnson, A Dictionary of the English Language, (London: J. and P. Knapton; T. and T. Longman; C. Hitch and L. Hawes; A. Millar; and R. and J. Dodsley, 1755). [Reproduction edition by Times Books Limited, (London, 1979.)] The same definition and pronunciation is given in an edition of Johnson’s Dictionary published in Philadelphia by Johnson & Warner in 1813 and in an edition published in London by Hurst, Rees, Orme & Brown in 1818.

William Perry, The Royal Standard English Dictionary, (Boston: I. Thomas & E. T. Andrews, 1788). The same definition and pronunciation is also given in an edition of Perry’s Dictionary published by the same publisher in 1800.

Thomas Sheridan, A Complete Dictionary of the English Language, both with Regard to Sound and Meaning, (2d Ed.) (London: C. Dilly, 1789).

John Walker, A Critical Pronouncing Dictionary and Exposition of the English Language, (3d Ed.) (London: Printed for the Oriental Press by Wilson & Co. for the author, 1802). Walker’s definitions and pronunciation guide are seen in dictionaries published in America and England as late as 1864.

Noah Webster, A Compendious Dictionary of the English Language, (Hartford: from Sidney’s Press for Hudson & Goodwin, Booksellers, 1806).

[10] Alexander Pope, An Essay on Man, (London: Warburton, 1751). Epistle IV, Lines 253-256. [Reproduction: Frank Brady, ed. (New York: Macmillen, 1965).]

[11] Samuel Johnson, A Dictionary of the English Language, (Philadelphia: Johnson & Warner, 1813); and Samuel Johnson, A Dictionary of the English Language, (London: Hurst, Rees, Orme & Brown, 1818). Vol. 2. (This edition includes words not found in the Dictionary of Dr. Johnson, and additions or alterations made with respect to etymology, definition or example. Where such alterations have been made, they are indicated with * or †. The entry for Huzza has neither mark, indicating that as late as 1818 “Huzza” was still to be used and pronounced in the same way that it had been in Johnson’s time.

[12] The Oxford English Dictionary, (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1933) [Reprinted: 1961]; Webster’s New World Dictionary, Third College Edition, (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1984); Merriam-Webster’s Collegiate Dictionary, Tenth Edition, (Springfield: Merriam-Webster, 1994).

[13] David Garrick, The Farmer’s Return from London. An Interlude, as it was performed at the Theatre Royal in Drury Lane, (London: printed by Dryden Leach for J. and R. Tonson in the Strand, 1762), lines 37 to 49.

[14] Anon., “English Courage Display’d, or Brave News from Admiral Vernon,” ca. 1741, (attributed to “A seaman on board the Buford, the admiral’s ship, and sent here from Jamaica.”) [In C. H. Firth, ed. Naval Songs and Ballads, (London: Navy Records Society, 1906), 177-178.]

[15] “Crito,” “An Ode to Peace,” The General Magazine, (Newcastle Upon Tyne: John Gooding, October, 1748) 542 & 543.

[16] Anon., “American Freedom,” 1775. [In Vera Brodsky Lawrence, Music for Patriots, Politicians and Presidents, (New York: MacMillan, 1975).]

[17] Anon., “Keppel Forever,” 1779, Roxburghe Ballads, 8: 325. [Reprinted in Naval Songs and Ballads, 257-258.]

[18] Captain George Bush, “The Drum,” ca. 1779. [In Kate Van Winkle-Keller, Songs from the American Revolution, (Severna Park, MD: The Colonial Music Institute, 1992.)]

[22] Anon., “Copenhagen,” ca. 1806, Laughton’s Nelson Memorial, 196. [Reprinted in Naval Songs and Ballads, 290-295.]

[23] James Campbell, Glorious Naval Victory Obtained by Commodore Bain Bridge of the United States Frigate Constitution over His Britannic Majesty’s Frigate Java, (Boston: Printed and sold by Nathaniel Coverly, JNR, Corner Theater Alley, ca. 1813). [In American Naval Songs and Ballads, (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1938), 129-131.]

[24] Anon., “The Capture of St. Jean D’Acre,” ca. 1840, from the Madden Collection, Country Printers, [Reprinted in Naval Songs and Ballads, 333-334.]

[25] Only two examples in which the rhyme indicated a pronunciation of “Huzza” other than “Huzzay” were discovered in the research for this article. One is a song entitled “Ye Tories all Rejoice and Sing” [in Jerry Silverman, Songs of Ireland, (Barking: Mel Bay Publications, 1991.)]. Written in 1776, it suggests the “Huzzah” pronunciation by rhyming “Huzza” with “law,” and “saw” in the following passage:

And curse the haughty Congress

Huzza! Huzza! And thrice Huzza!

Return peace, harmony and law!

Restore such times as once we saw

And bid adieu to Congress.

The other is Rogers & Victory. Tit for Tat (Boston: Nathan Coverly, 1808) [Reprinted in Robert W. Nesser, American Naval Songs and Ballads, 82-85], which attempted to put a brave face on the 1807 loss of the USS Chesapeake. The intended rhyme is difficult to interpret. The relevant passage is:

Our cannon roar’d, our men Huzza’d

And fir’d away so handy

Till Bingham struck, he was so scar’d,

At hearing doodle dandy.

In this period many persons spelled words as they spoke them – phonetically. If “scar’d” was intended to be pronounced with the long “A,” the indicated pronunciation of “Huzza’d” would be close to “Huzzay.” If “scar’d” was intended to be pronounced in an English West-Country accent (eg: “Arr, Mateys”) the indicated pronunciation of “Huzza’d” would be something like “Huzzahr’d.” Other pronunciations are also possible.

[26] Noah Webster, A Compendious Dictionary of the English Language (Hartford: from Sidney’s Press, for Hudson & Goodwin, Booksellers, 1806).

[28] Noah Webster, An American Dictionary of the English Language (New York: Harper Bro’s., 1848), 507

[29] Noah Webster, An American Dictionary of the English Language (Springfield, Mass.: George and Charles Merriam, 1860).

29 Comments

I’m convinced, you might say!

The way to say it is “Huzza!”

My blog:

History: Bottom Lines

I too am convinced! However, I’m somewhat amazed that Noah Webster (1758-1843) was still revising his dictionary after 1843. That’s dedication. Perhaps rumors of his death were somewhat exaggerated? In any case, Huzza! for a very fine article.

Hugh,

Sorry to be so long replying. I came down with some bug and am just now getting back to something resembling normal.

You are right, of course. For Webster to have been personally revising his dictionary after 1843 would have been remarkable dedication. Of course he wasn’t. But he had set the direction. His dictionary has undergone constant revisions even to the resent day. We probably can never know whether the later changes to HUZZA were taken from notes he had left behind or were the work of subsequent editors following the direction he had set.

But by the mid nineteenth century Webster’s Dictionary had become pretty much standard throughout large parts of the U.S. So no matter who actually made the later revisions to HUZZA, I think Webster deserves the credit.

We used to cry Huzzah! Huzzah!

Then overwhelming evidence we saw

To make us reconsider our ways

And give a new cheer of Huzzay! Huzzay!

(Apologies for the awful poetry.)

Love the tracing of the linguistic changes. I’ve seen some of Webster’s early spelling books (an edition published in 1796 or 1797 if I remember right), and in it he advocates very forcefully for the idea of teaching children to spell using linguistic aides, rather than rote memorization. His dictionary reflects the linguistic efforts by changing the spellings of many words to closer reflect how they were being pronounced. Some of the changes caught on (the dropping of the u in words like color, the changing of the ‘ence’ ending to ‘ense” as in defense and the ‘ise’ to ‘ize’ as in agonize). Some didn’t such as spelling women ‘wimmen’.

Here’s a Google Books Ngram graph showing how “hurrah” overtook “huzza” in written English—but not until the mid-1800s.

Dear Mr. Bell,

Thank you for putting me onto this site. I was unaware of its existence until your posting. It is now in my bookmarks.

As I studied the chart, I noticed that the Huzzah pronunciation that is so popular among living historians and reenactors today had not been included among the several pronunciations tested. When I added Huzzah and re-ran the test I was surprised to see that Huzzah apparently did not appear until about 1840 and that it ranked below every other variation of this cheer, barely getting above the zero line on the chart from circa 1840 to today.

Very interesting and revealing! I had thought that Huzzah would have been much more popular than that, especially during the period of the American Civil War.

Intrigued, I dug a little deeper. Noting that the chart that you led me to was based on written English (both American and British), I changed the search criteria to include Huzzah and only American English written occurrences. Again, revealing! Huzza shows a very high and sharp peak just at the time of the American Revolution, then tails off as we go into the nineteenth century. Hurrah, on the other hand, scores very low until about 1840, peaks in the 1860’s and 70’s, then tails off along with the other variants as we move into the 20th century. Huzzah, interestingly, barely appeared on the chart.

Finally, I ran the same chart on British English. The results were similar, with Huzza peaking at about the time of the American Revolution, then tailing off into the nineteenth century, Hurrah appearing at about the turn of the nineteenth century and peaking about the time of the American Civil War before tailing off, and Huzzah barely appearing at all.

All this leads me to wonder — just where did the living history and reenactment community get the Huzzah cheer that we have used pretty much unquestioningly for decades?

I thank the author for this exhaustively researched article. Noah Webster was certainly a strong minded individual who tried to shape American English as he saw fit, or rather as he heard it spoken, already quite distinct from the Mother tongue. One thing I noticed, however, is that most of the dictionaries cited do NOT state how such a huzza was vocalized… except for Noah Webster, opinionated fellow that he was. By this I mean, today we all routinely say “they shout” or “they cheer” and yet we KNOW they, whomsoever “they” may be, do not yell SHOUT! or CHEER! but ejaculate some other noise. Read most of the dictionary definitions cited and most do not SAY “the sound of the cheer is pronounced thus…. ” Rather they define the act or name of the exclamation. A notable exception is Webster, who does, and who should at least qualify as a sound primary source for southern New England in 1828.

The early SONGS I grant you are better evidence for how said cheer may have been pronounced in some times and places, often notoriously stretched rhyme schemes aside. But as for me, a Connecticut Yankee born and bred, and a historian of antebellum New England, I am reluctant to completely dismiss another Connecticut Yankee who was a lexographer there and then. He may well have made mistakes in etymology, and Americanized British spelling, but the man spent his life studying words and speaking IN that time and place.

I am especially unconvinced by the argument that due to the Webster dictionary and Union victory in the Civil War everyone stopped saying Huzza and now people cheer Hurrah, Hurray, and the US Marines tellingly Hoora. NOT because that is how a lot of people already were voicing it?? Respectfully, that doesn’t ring true to me. As a small example, in the popular CONFEDERATE song “Bonnie Blue Flag” isn’t the refrain,

Hurrah! Hurrah!

For Southern rights hurrah!

Hurrah for the Bonnie Blue Flag

That bears a single star?

Was this Websterized after Appomattox? No, it evolved over time, as language does. And the author was born and raised in England and settled in Arkansas in 1849. Webster may well have influenced him, as he has so many, but I still think this is telling. And as for changes in the 1848 and 1860 Webster dictionaries cited, the evolving definitions and pronunciations were no longer “his” as stated. Noah Webster died in 1843, and rights to his dictionary were sold to the Merriam brothers.

This is an interesting article with some interesting insights, but to my mind it contains some flawed reasoning disguised by abundant citations. I believe the true point should be that people likely made different sounds as they cheered in different places at differed times, since they certainly pronounced a LOT of things differently as well. For me the lesson to be taken from this is that an affected “Huzza!” or “Huzzay!” MAY fit the time and geography of a reenactor’s impression, but one size or more aptly sound does NOT fit all! Like costumes, language should fit properly to be considered authentic.

Dear Mr. Kelleher,

Thank you for your detailed and thoughtful response to my article “You say Huzzah, They said Huzzay.” You make several interesting points.

One seems to be that the contemporary dictionary references to Huzza do not say “the sound of the cheer is pronounced thus … ,” and that therefore we cannot know what the actual vocalization of the shout that they called huzza really was or how it was to be pronounced. In that regard I would call your attention to the citations from Sheridan and Alexander that are included in the article.

Sheridan includes definitions of “Huzza”, and “To Huzza.” He defines “Huzza” as an “interjection, a shout, a cry of acclimation,” “To Huzza” as “To utter acclamation” and “To receive with acclimation.” Clearly, to Sheridan, the act of Huzzaing (shouting) and the shout itself were the same word, to be pronounced in the same way.

Alexander uses only one entry in which he defines the act of cheering as Huzza, but also defines the interjection (i.e. the vocalization) of the cheer as the same word with the same pronunciation.

Although I did not include the entire passage from Walker in the article because of space considerations, he also defines the act of cheering as Huzza and the cheer itself as Huzza. Similarly Perry, who’s definition and pronunciation guide I omitted for the same reason defines the interjection (vocalization) of the cheer as Huzza and gives the Huzzay pronunciation. (For the full list of period dictionaries which indicated the proper pronunciation of Huzza, see endnote 5.)

To me the available dictionary evidence is compelling that in the eighteenth century English speaking world the act of cheering (shouting with acclimation) and the cheer/shout/vocalization itself were the same word and were to be pronounced in the same way – i.e. “Huzzay.”

If further evidence is desired, comparing the poetry, songs and similar rhyming passages that were meant to be spoken with the dictionary evidence is further confirmation that Huzzay was the preferred if not the dominant pronunciation of Huzza in the eighteenth century. It goes both ways. The prescriptive evidence of the dictionaries and the descriptive evidence of the songs, poetry, etc. are mutually supporting and consistent with one another.

As to Webster and your comment that you are “… reluctant to dismiss another Connecticut Yankee who was a lexicographer there and then” I would refer you to Webster’s first dictionary published in 1806 (see endnote 26 for the full citation) in which he defined Huzza and its pronunciation in the same way as Sheridan, Alexander, Walker and the other English lexicographers. Although the reference constitutes only a short two line passage in the article (the full citation was omitted because of space limitations), in 1806 that other Connecticut Yankee was telling his readers to pronounce Huzza as Huzzay. He changed later. But in 1806 he gave the pronunciation of Huzza as Huzzay.

Did everyone stop saying Huzzay and start saying Hurray, Hurray and Hoora due to the Webster dictionary and the Union victory in the Civil War? Hardly. These things never happen immediately or as the result of a single or even a few clearly defined events. As I pointed out in the article, as late as 1763 the Palmetto dictionary, published in Richmond, contained the traditional definition and pronunciation of Huzza. I’m sure that many people who had grown up with the ”old” pronunciation continued to use it until the day they died. But as Webster’s dictionary supplanted the older ones both in the United States and in Great Britain, younger generations grew up with the words, spellings, meanings and pronunciations that Webster’s dictionary prescribed. They had no other readily available guide. So, as old generations died out and were replaced by younger ones, the old pronunciation of Huzza, indeed the word itself gradually died out and disappeared from common usage.

Finally, let me address your point that “… people likely made different sounds as they cheered in different places at different times …” and that one pronunciation may not fit all impressions. You are right, of course. And if one has primary source documentation that another pronunciation is the correct one for their particular impression, they should by all means use it.

What I attempted to do in this article was to document what appears to have been the predominant pronunciation of a ubiquitous cheer in the English speaking world of the eighteenth century. The evidence that Huzza should be pronounced to rhyme with words like “say,” “hay,” “play” and “delay” is compelling. In the absence of audio recordings we cannot be absolutely certain that the entire manner of speaking the English language has not changed dramatically in the course of 250 years and that Huzza was not really pronounced Huzzah. What we can be sure of, however, is that in the eighteenth century Huzza was pronounced to rhyme with words such as “play,’ “say,” “day,’ hay” and “delay.” If, in talking with the public we are going to pronounce words like “play,’ “say,” “day,’ hay” and “delay” as we pronounce them today, I think we have an obligation to be consistent and pronounce Huzza to rhyme with them.

Thank you again. For the 18th century you made a detailed and convincing case with which I have no argument. Huzza!

Sorry. My tablet jumped the gun. I meant to say huzzay of course. My sincere apologies.

May I respectfully reply that although Mr. Fuss has successfully shown that “Huzzay” was one pronunciation of the cheer we all know and love (which is not news to those of us who study eighteenth-century English), he has not proven that it was the most popular pronunciation. And he has completely overstated his case when he indicates that “Huzzah” should no longer be used. There is abundant evidence in both rhyming and spelling that “Huzzah” was used—a lot. Here is a summary of why I believe that Mr. Fuss has failed to prove his assertion that “the virtually universal pronunciation among English speakers was “Huzzay”:

• When the word is spelled “Huzza,” the most popular spelling, it is impossible to tell how it was pronounced outside of rhyming evidence. Unless this spelling appears in a rhyme, therefore, it cannot be counted as evidence of either one pronunciation or another. Most of the evidence in the popularity contest between the two pronunciations, therefore, is lost to us as unusable.

• We know that the pronouncing dictionaries of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries preferred “huzzay” as the more genteel pronunciation. Mr. Fuss’s assertion that “the obvious first place to go for pronunciation guidance is dictionaries,” however, is not so for the mid-to-late eighteenth centuries. These dictionaries were, as he notes, prescriptive. What he does not appear to take into consideration, however, is that they were written to guide those who were not as genteel to the newly stylish pronunciations of English words. The upper classes were, at this period, consciously changing their vowel sounds to separate themselves from those below them who were increasingly able to emulate them in material goods like dress and furniture. Language and etiquette, those less tangible things, were changing so that the “uppers” could continue to distance themselves from the “lowers.” These dictionaries, therefore, consciously do not reflect either historical or popular pronunciation. They reflect new, elite pronunciation. (For a good scholarly treatment of this change in language and the function of dictionaries, see, for example, Joan Beal, English Pronunciation in the Eighteenth Century, Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1999.) Dictionary writers’ attitudes toward popular speech is illustrated by John Walker in his A Critical Pronouncing Dictionary and Expositor of the English Language (London 1791), p. viii: “nor will a multitude of common speakers authorise any pronunciation which is reprobated by the learned and polite.” In other words, no matter how many people used a particular pronunciation, the learned and polite (including dictionary makers!), who were trying to change English pronunciation, were the ultimate authorities—and the popular pronunciation would be disregarded in the dictionary. [Even so, Perry (1788) and Webster (1806) offer an alternative pronunciation to “huzzay,” in which the -a may be pronounced to rhyme with the -a in “ask.” This -a is probably not pronounced as modern Americans do, but more like the British “awsk,” and thus “huzzah.”]

• Mr. Fuss’s rhyming evidence is almost all British and/or literary. Again, this could reflect a more elite mindset. Poems and published songs were not usually produced by, as he says, “the common people in the streets and the soldiers in the field,” but by playwrights, authors, and literary gentlemen. These works should not be assumed to be representative of the actual speech of common people. The middling and lower orders of society were less likely to produce items for publication, so their speech and pronunciations are under-represented. We can’t know what pronunciation was most popular from these sources.

• In this article, there is only one example of American Revolutionary period rhyming evidence of the “huzzah” pronunciation, and it is relegated to a footnote:

Huzza! Huzza! And thrice Huzza!

Return peace, harmony and law!

Restore such times as once we saw

And bid adieu to congress.

This piece, published originally in Philadelphia in Benjamin Towne’s Pennsylvania Evening Post in 1776 is American evidence of the pronunciation of “huzzah” during the American Revolution. Why it is discounted as evidence that at least some Americans of this era said “Huzzah” is puzzling to me.

But here is a stanza from “The Political Balance; or, The Fates of Britain and America compared. A Tale” that should have been included, as well:

When gods are determin’d what project can fail?

So they gave a fresh shove and she mounted the scale;

Suspended aloft, Jove view’d her with awe—

And the gods, for their pay, had a hearty—huzza!

[The Freeman’s Journal: or, The North-American Intelligencer, Philadelphia, 3 April 1782.]

There clearly is rhyming evidence to support the use of “huzzah,” but it is not well-represented in this article.

• Spelling evidence makes it very clear that Noah Webster did not change “Huzzay” to “Huzzah,”—“Huzzah” predates Webster by more than a century. A spelling of an English word with a final “ah” or “aw” has never indicated a long -a sound like “ay.” A quick glance at the Oxford English Dictionary is enough to indicate that “huzzah” had a longstanding usage: “At his passing over the Bridge, the Castle saluted him with five great Guns, and closed the farewell with three Hussaws, Seamen like” (1679). The OED also cites a 1705 appearance: “They drink a Health–Huzzah–to the Prosperity of the Highflown . . Ceremony-Monger.” A simple search of “huzzah” on the Eighteenth-Century Collections Online database reveals abundant examples of this spelling/pronunciation across the whole eighteenth century.

• A larger view about how final –a was thought about and pronounced in general would be beneficial. In John Walker’s 1798 edition of his pronouncing dictionary, he makes it clear what he thinks of any sound but the long –a (“ay”) sound at the end of an accented syllable:

It must not be dissembled, however, that the sound of a, when terminating a syllable not under the accent seems more inclined to the Irish than the English a, and that the ear is less disgusted with the sound of Ah-mer-I-cah than of A-mer-I-cay . . .

Clearly, he doesn’t like the “ah” sound at the end of a word in an accented syllable, so “Americah” and “Huzzah” would not appear in his dictionary as proper pronunciations, but just as clearly, people were pronouncing these words with an “ah” at the end, or he wouldn’t be declaiming against it.

In summary, Mr. Fuss’s article presents good evidence that “Huzzay” was the preferred elite, literary pronunciation. It does not, however, prove that it was the most popular pronunciation. Moreover, if we have evidence that Americans and Englishmen were using the pronunciation “huzzah” in the eighteenth century (particularly during the Revolutionary period), why would we say it is inappropriate to use it? “Huzzah” or “huzzay”—cheer on!

I read Cathy Hellier’s reply to my article “You say Huzzah, They Said Huzzay” with interest and appreciation. It is the kind of interchange represented by Ms. Hellier’s critique that enables us to acquire new information, expand our knowledge and our skills and become better researchers, interpreters, living historians and reenactors. Providing a forum for such interchanges that is one of the great values of Journal of the American Revolution.

Ms. Hellier is a professional historian on the staff of Colonial Williamsburg. I value and respect her opinions, even when I find myself in disagreement with them. Her critique is respectful and thoughtful. It deserves a respectful and thoughtful response. So here goes.

I believe Ms. Hellier’s arguments can be grouped under two major headings. One, that the word that is spelled HUZZA is not the only word used as a cheer in the English speaking world of the eighteenth century and indeed is not the “dominant and almost universal cheer” that I characterized it as in my article. The other is that regardless of whether HUZZA was almost universal, dominant, or merely one of many cheers of the period , it is impossible for us to know with certainty how it was pronounced by people living before the advent of audio recording, and that therefore any pronunciation is as valid as any other.

There is no reason to doubt that a cheer spelled HUZZAH coexisted with the cheer spelled HUZZA. Ms. Hellier mentions the “…one example of American Revolutionary period rhyming evidence of the “huzzah” pronunciation …” in the article, noting that “… it is relegated to a footnote” and expressing puzzlement that it “… is discounted.”

That example of rhyming evidence for huzzah is the only example that I and three other researchers found in several years of trying. It was reported in an endnote rather than in the body of the article because of space limitations. The editors of Journal of the American Revolution requested that I “… re-edit the original version, preferably [to] 3,500 words or fewer.” This necessitated substantial cutting. One of the things that got cut was the text citation of the example of rhyme indicating a pronunciation of huzzah (along with another example in which the indicated pronunciation was something like Huzzargh). However, I was unwilling to have the article totally ignore these exceptions. So I put them in an endnote where the word count would not be charged against my 3,500 word limit.

Ms. Hellier goes on to offer another example of rhyming evidence for the huzzah pronunciation. That makes two such examples. In the article I included twelve of the example of rhyming evidence for the huzzay pronunciation that I and my friends had found. I did not include others in the text because of the space limitation. And I did not include them in the endnotes because I felt that twelve was sufficient to make the point. Perhaps, with further research, additional examples of rhyming evidence for the huzzah pronunciation will be found. Perhaps additional examples of rhyming evidence for the huzzay pronunciation will also be found. But as of now the rhyming evidence that we have is heavily in favor of huzzay as being far more widely employed during the eighteenth century than huzzah.

Ms. Hellier then goes on to discuss spelling evidence from the entire corpus of literature, not just rhyming literature, concluding with “A simple search of “huzzah” on the Eighteenth Century Collections Online database reveals abundant examples of [huzzah]” Without getting into a discussion of what number of examples constitutes “abundant,” I would suggest that any number of examples in isolation is of little use. What I believe to be more useful is a comparison of the number of times “huzzah” appears in the literature versus the number of times that “huzza” and related spellings appears in the literature. Even that would be of little use unless the comparisons were reported by year of publication within the time period studied. Ms. Hellier offers no insight into what such a search would reveal.

Fortunately, we have available the results of a similar search. In an excellent example of the value of exchanges such as this, on April 22, in his reply to my article, J. L. Bell provided a link to Google Books Ngram Viewer. Google Books Ngram Viewer is a sophisticated software application that employs Optical Character Recognition (OCR) technology to scan the words in a collection of books published between 1500 to 2000. I was not able to determine number of books in the collection that Ngram employs. But it is based on a project entitled “Quantitative Analysis of Culture Using Millions of Digitized Books,” and the Ngram web site describes a selective, restricted sub-set of that collection as containing one million books. Hence the total collection is probably in the range of several million books.

Ngram reports the occurrence of words designated by the user as a percentage of all the words in all the books in the collection, by year, in graphic (Ngram) format. The absolute percentages reported are, not surprisingly, very small ― roughly in the range of one “hit” in about 10 Billion words. But it is not the absolute percentage of occurrence of a word that is of most use in discussions such as this one. It is the relative percentage occurrence of a word seen in comparison to the percentage occurrence of other words over time that is most useful and revealing.

I ran an Ngram graph for the years between 1700 and 2000 on huzza, huzzah, hussay, hussah,husaw,hooray, hooraw, hoorah, hurray, hurrah, hurraw and several other related possible spellings against the combined British/American collection. Several of the spellings yielded zero “hits.” Others yielded very low levels of “hits.”The only two spellings that yielded a significant number of “hits” were huzza in the eighteenth century and hurrah in the nineteenth century, where their occurrence was so much greater than any/all other spellings as to be dominent.

I then ran another search limited to huzza, hurrah and huzzah. The resulting Ngram graph indicated that during the eighteenth century the huzza spelling dominated, starting in about 1710, peaking between about 1760 and 1770 and continuing at high level until about 1850, at which time it began a steady decline to the present when it appears hardly at all. The hurrah spelling first appeard on the Ngram graph in about 1750, but at a very low level. It continues at a low level until about 1825, at which time it started a fairly rapid rise to a peak at about the time of the American Civil War, after which its usage also declined. The Ngram graph indicated an quite low occurrence of the huzzah spelling throughout the period searched. Although we know from the examples presented in the article and by Ms. Hellier that the huzzah spelling was in use during that period, the Ngram graph indicated such a low occurrence that it’s graph line barely rose above zero throughout the entire three hundred year period

Finally, I ran separate Ngram graphs for huzza, hurrah and huzzah against British literature only and against American literature only. The results, while similar overall to the Ngram graph for British and American literature combined, yielded some additional insights. The Ngram graph line for huzzah was close to zero in both instances. The Ngram graph line for hurrah peaked in the same period in both American and British literature, but showed a higher occurrence in American literature than in British literature. The Ngram graph line for huzza in British literature showed a brief, high peak around 1710-1720, then dropped off until about 1750, at which point it regained its former popularity, reaching another peak in about 1770-1780 before beginning its slow decline. The Ngram graph line for huzza in American literature exhibited a very high, sharp spike of popularity in the last quarter of the eighteenth century, after which it dropped to a much lower level around 1800 and steadily declined thereafter.

It is said that a picture is worth a thousand words, so I have inserted links of the three Ngram graphs comparing the use of huzza, huzzah and hurrah in English, British English, and American English.

In summary, Ms. Hellier maintains that I overstated my case and failed to prove my assertion that huzza, pronounced to rhyme with words ending in “ay” such as “day,” “pray,” “say,” “may,” “away,” and “play” was the common and indeed virtually universal cheer of the English speaking world in the late eighteenth century. She offers in support of her position one new piece of rhyming evidence for huzzah, and the declaration that “A simple search of “huzzah” on the Eighteenth Century Collections Online database reveals abundant examples of this spelling/pronunciation across the whole of the eighteenth century.” but does not provide any evidence to support her declaration. Even with the addition of Ms. Hellier’s additional example of rhyming evidence for huzzah, the rhyming evidence that we have is still heavily in favor of huzza pronounced huzzay. The additional evidence from Google Ngrams, shows that the appearance of huzza in eighteenth century literature massively overwhelms the appearance of huzzah or any other variation of that cheer and is further evidence of the dominance of huzza. While huzza was not the only cheer of the period, I believe that the available evidence is compelling that the cheer spelled huzza was so close to being the universal cheer of the day as to be, for all practical purpose, indistinguishable from it.

But what does this mean for historical interpreters, reenactors and others who interact with the public at historic sites, commemorations, celebrations and similar events?

Ms. Hellier presents a closely reasoned argument to the effect that it is not possible to know with certainty how the cheer spelled huzza and rhymed in the printed literature of the period with words such as “day,” “pray,” “say,” “may,” “away,” “play” and other words ending in “ay” was actually verbalized by eighteenth century English speakers ― be they members of the educated upper classes, the illiterate lower classes ,or any other segment of society. She concludes that in the absence of audio recordings it is not possible to prove beyond doubt how any words were pronounced by anyone and that therefore huzzah is just as valid a pronunciation of huzza as huzzay.

Proof beyond all doubt is an extremely difficult, often impossible standard to meet. That is one of the principal reasons why our legal system is based on proof beyond reasonable doubt. To me the standard of reasonable certainty is far more useful than a standard of certainty beyond doubt.

Ultimately each of us is faced with a choice. We can choose to be guided by what we do know. Or we can choose to guided by what we do not know. I believe that it is far more useful to be guided by what we, with reasonable certainty, do know.

We know with reasonable certainty that the cheer spelled huzza appears so widely and frequently by comparison to any other spelling in the literature of the eighteenth century as to overwhelm any/all of them.

We know with reasonable certainty from the prescriptive evidence of period dictionaries that the “a” in the cheer spelled huzza was supposed to be pronounced with the long “a” sound to rhyme with words ending in “ay” such as “day,” “pray,” “say,” “may,” “away,” and “play” ― i.e.: huzzay.

We know with reasonable certainty from rhyming literature evidence that the cheer spelled huzza was, with few exceptions, rhymed in poetry and song with words ending in “ay” such as “day,” “pray,” “say,” “may,” “away,” and “play” ― i.e., huzzay.

From this I believe that we can reasonably conclude that the huzzay pronunciation was the pronunciation that people of all or at least most classes of society expected to hear. David Garrick’s short afterpiece, “The Farmer’s Return from London,” in which huzza is rhymed with “say” was written for performance at the Drury Lane Theater in London. Any other pronunciation of huzza would have been jarringly out of place to his audience, which consisted of high, middling and lower class patrons. Clearly they expected to hear huzza pronounced huzzay. Several of the songs in which huzza was rhymed with words ending in “ay” were written by commoners ― e.g.: a seaman on board the Buford, and a Boatswain’s Mate on board the USS Constitution. And many of these songs were published as penny broadsides who’s songs were sung in the streets by commoners to commoners and gentry alike.

I believe that we can reasonably conclude that the pronunciation of words ending with “ay,” the words with which the cheer spelled huzza was rhymed, was probably little if any different from the way in which those words are pronounced today. Comparison of the pronouncing guides in eighteenth century dictionaries with the pronouncing guides in modern dictionaries reveals a very high degree of congruence, even to the use of the same words as examples of proper pronunciation.

In summary, then, I suggest that Ms. Hellier has failed to prove her assertion “…that “Huzzah” was used ― a lot” and that the evidence available at this time is compelling that the cheer spelled huzza and pronounced huzzay was dominant over any/all other spellings/pronunciations in both England and America during the eighteenth century.

The evidence on both side of the huzzay/huzzah issue has been presented. It is now up to each individual to evaluate it and decide what they will do with it.

Mr. Fuss is mistaken about my argument. He summarizes it thus:

I believe Ms. Hellier’s arguments can be grouped under two major headings. One, that the word that is spelled HUZZA is not the only word used as a cheer in the English speaking world of the eighteenth century and indeed is not the “dominant and almost universal cheer” that I characterized it as in my article. The other is that regardless of whether HUZZA was almost universal, dominant, or merely one of many cheers of the period , it is impossible for us to know with certainty how it was pronounced by people living before the advent of audio recording, and that therefore any pronunciation is as valid as any other.

Let me address Mr. Fuss’s first summary statement. My argument is that there are two contemporaneous pronunciations of one word spelled various ways, but most often spelled HUZZA. Mr. Fuss later says that “there is no reason to doubt that a cheer spelled HUZZAH coexisted with the cheer spelled HUZZA.” The basic difference between his summation and my argument is that he appears to believe that the spelling Huzza stands in eighteenth-century English for only one pronunciation–the one with the long -a and thus HUZZAY, for clarity’s sake–and that the word pronounced HUZZAH stands for the pronunciation ending with an -aw sound, but is never spelled HUZZA. This is the assumption that underlies his argument, but I argue that this is erroneous. Spelling was not standardized during the eighteenth century. I have provided rhyming evidence that HUZZA was sometimes pronounced HUZZAH in America during the Revolutionary period.

We simply can’t know, therefore, apart from rhyming evidence how a word spelled HUZZA was pronounced in any given example. Ngram charts are, therefore, useless, as they prove nothing about pronunciation, but only spelling.

We can say no more, then, about the popularity of both pronunciations. Both were contemporaneous, and both were sometimes spelled Huzza.

As to his second summary of my argument, it is true that I do not accept the premise that HUZZAY was “almost universal” or “dominant” for the reasons stated above. It is not true that I believe that it is “impossible for us to know with certainty how it was pronounced by people living before the advent of audio recording.” I believe that we have identified the two pronunciations discussed above with valid evidence. I also did not argue “that therefore any pronunciation is as valid as any other.” I simply argued that we do not have enough evidence to conclude that HUZZAY or HUZZAH was the dominant pronunciation because (1) the most popular spelling HUZZA is pronounced both ways, (2) rhyming evidence is primarily produced by the literate and/or literary, leaving the pronunciation of the majority of people in doubt, and (3) prescriptive sources indicate that words ending with -a were pronounced with both long -a and -aw sounds. I argue, therefore, that since we have evidence of both the HUZZAY and HUZZAH pronunciations, both are valid.

I hope this helps to clarify.

I appreciate Mrs. Hellier’s response in which she attempts to clarify her position and mine with respect to the dominant eighteenth century pronunciation of the cheer spelled HUZZA. Let me take this opportunity to attempt to clarify a few points on which it appears that there is still seems to be some confusion and misunderstanding.

In her reply Ms. Hellier says “The basic difference between his summation and my argument is that he appears to believe that the spelling Huzza stands in eighteenth century English for only one pronunciation–the one with the long -a and thus HUZZAY, for clarity’s sake–and that the word pronounced [spelled?] HUZZAH stands for the pronunciation ending with an -aw sound, but is never spelled HUZZA. This is the assumption that underlies his argument, but I argue that this is erroneous.”

Here, I believe that Mrs. Hellier has misinterpreted my methodology. There was no such underlying assumption. As I pointed out in the introduction to my original article, “There are at least forty different ways in which the word “Huzza” might be pronounced in the English language. Which of these forty+ possible pronunciations was in use in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries?” Clearly, any spelling of any word in the English language can be pronounced in a number of different ways. HUZZA is no different. Three examples of rhyming poetry, —two in endnote 25 to my original article and one that Ms. Heller discovered — have been unearthed to date which indicate a pronunciation of HUZZA other than HUZZAY.

The issue as I see it is not whether the spelling of HUZZA uniquely determines its pronunciation, but rather “Which of the forty-plus possible pronunciations [of HUZZA] was [dominant] in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries?” The preponderance of literary evidence indicates that the dominant pronunciation of the word spelled HUZZA rhymed with words like “say,” “gay,” “day” and “away.” Similarly the prescriptive evidence of eighteenth century dictionaries overwhelmingly indicates that the dominant pronunciation of the word spelled HUZZA rhymed with words like “say,” “gay,” “day” and “away”.

Later she says “Ngram charts are, therefore, useless, as they prove nothing about pronunciation, but only spelling.”

The Ngram charts were introduced in response to Ms Hellier’s assertion that “A simple search of “huzzah” on the Eighteenth Century Collections Online database reveals abundant examples of [huzzah].” I interpreted this as “… abundant examples of [a word spelled HUZZAH].” If I misunderstood her intent, I apologize.

Finally, she says “… We do not have enough evidence to conclude that HUZZAY or HUZZAH was the dominant pronunciation because (1) the most popular spelling HUZZA is pronounced both ways, (2) rhyming evidence is primarily produced by the literate and/or literary, leaving the pronunciation of the majority of people in doubt, and (3) prescriptive sources indicate that words ending with -a were pronounced with both long -a and -aw sounds. I argue, therefore, that since we have evidence of both the HUZZAY and HUZZAH pronunciations, both are valid.”

As to point #1, “… the most popular spelling HUZZA is pronounced both ways” I do not disagree. Other pronunciations of the HUZZA clearly co-existed with HUZZAY. The currently available research has turned up examples indicating three pronunciations of HUZZA — far more for HUZZAY than for HUZZAH, but clearly other pronunciations co-existed.

As to point #2, ” … rhyming evidence is primarily produced by the literate and/or literary, leaving the pronunciation of the majority of people in doubt.“ I agree that rhyming evidence was produced primarily by the literate and/or literary. But not exclusively. There are, as I noted in my article and my initial response to Ms. Hellier, examples of rhyming evidence produced by common people.

However, the pronunciation of the producers of rhyming works is only half of the story. Those rhyming works — especially the songs and the plays — were meant to be heard by many, the literate and the illiterate alike. What pronunciation did all these folks expect to hear? The evidence indicates that they expected to hear HUZZA rhymed with “say,” “gay,” “day” and “away.” The strongest piece of evidence (at least to me) is the use of HUZZA in David Garrick’s rhyming afterpiece The Farmer’s Return from London. In it Garrick, arguably the premier playwright of his time who was writing for an audience at the Drury Lane theater that consisted of persons from all stations of society, rhymed HUZZA with “say.” I believe that it is extremely unlikely that he would have done this unless the HUZZAY pronunciation was the pronunciation that his audience expected to hear.

As to point #3 “… prescriptive sources indicate that words ending with -a were pronounced with both long -a and -aw sounds. I argue, therefore, that since we have evidence of both the HUZZAY and HUZZAH pronunciations, both are valid.” Prescriptive sources do indeed indicate that many words ending with “a” were pronounced with the long “a” (ay) and that many other words ending in “a” were pronounced with the shorter “a” (aw) sounds — as well as many other words ending in “a” that were to be pronounced with one of the other possible pronunciations of “a.” But the available prescriptive sources indicate only one pronunciation for the final “a” in HUZZA. They are unanimous in indicating that HUZZA should should be pronounced to rhyme with words like “say,” “gay,” “day” and “away.”

Clearly both the HUZZAY and the HUZZAH pronunciations are valid in the sense that evidence has been found that both co-existed in the eighteenth century. But they are not equally valid. They are not (or should not be, in my opinion), interchangeable for use for use by historians and historical interpreters in their interactions with the public.

The central issue, in my view, is not whether the HUZZAH pronunciation of HUZZA is or is not valid. The central issue is which pronunciation of the word spelled HUZZA was the predominant pronunciation — the pronunciation that one would hear most often if one were to be transported back to eighteenth century England or America. The evidence, I believe, is compelling that it would be HUZZAY and that other pronunciations such as HUZZAH, while they existed, were seldom heard exceptions.

In summary then, I believe that the evidence we have available to us at this time clearly establishes that, while the HUZZAH pronunciation of the cheer spelled HUZZA existed, it was unusual, exceptional and uncommon, and that the HUZZAY pronunciation was dominant, common and expected.

It is my belief that historians, historical interpreters and others who portray history to the public have an obligation to portray what was usual, normal, and common, in preference to what was unusual, exceptional and uncommon (except in special presentations where it is clearly indicated that what is being presented was uncommon). Documentation for numerous “one-off” examples of all sorts of things can be found if one looks hard enough. If we interpret those exceptions to the public rather than the ordinary and common, we do the public a disservice by giving them a distorted and inaccurate picture of history. In the case of the pronunciation of the cheer spelled HUZZA, the evidence shows that a pronunciation to rhyme with words such as “say,” “gay,” “day” and “away” was the usual, common, normal pronunciation and that HUZZAH was an exception. So I believe that, in our interpretations to the public, we owe it to them to pronounce HUZZA to rhyme with “say,” “gay,” “day” and “away,” the words with which it was most commonly rhymed in the eighteenth century.

I hope this helps to dispel some of the confusion and misunderstanding that has arisen.

Mr. Fuss,

It seems we must agree to disagree about the nature of linguistic evidence (that which survives and that which doesn’t), the ways one can interpret this evidence, and what conclusions can be safely drawn from it.

I agree that your article presents good evidence that “Huzzay” was the preferred elite, literary pronunciation in Britain during this period based on your evidence of published sources.

I can’t agree that it was the most popular or common pronunciation in Britain or America. Too much evidence is missing.

May I gently suggest, however, that you take care not to confuse evidence with conjecture. For example, you state the following in regard to Point #2 immediately above:

“The strongest piece of evidence (at least to me) is the use of HUZZA in David Garrick’s rhyming afterpiece The Farmer’s Return from London. In it Garrick, arguably the premier playwright of his time who was writing for an audience at the Drury Lane theater that consisted of persons from all stations of society, rhymed HUZZA with ‘say.’ I believe that it is extremely unlikely that he would have done this unless the HUZZAY pronunciation was the pronunciation that his audience expected to hear.”

This statement is conjecture that could easily be countered by another conjecture that Garrick, who mixed in the highest social levels of society (because of his talent, not his birth), would use the most fashionable literary pronunciation to impress the nobility, without caring a fig for what the people in the cheap seats thought. Because we can’t know what Garrick’s motivation was unless he tells us (evidence), your statement and my counter-statement are both conjecture.

At this point, I will step out of the fray, having said my piece in as many ways as I can think of.

We share a common research question: “Which pronunciation of HUZZA was more common?” We don’t agree on a conclusion.

Ms. Hellier,

I concur. It does seem that we must agree to disagree on the issue of the most common eighteenth century pronunciation of the cheer HUZZA.

I do not view that as a bad thing.

Disagreement, in my view, is one of the most valuable engines that drive historical research to higher levels of perfection. When researchers disagree and defend their respective positions with documented evidence, with reason and with mutual respect, previously unknown information is brought to light. Errors, misunderstandings, misinterpretations and myths are exposed and resolved. The result is a more accurate and complete understanding of the world of the past, which benefits everyone.

Perhaps our agreement to disagree will stimulate us ― and others ― to dig more deeply into the HUZZAY-HUZZAH issue and find additional evidence that may one day enable us to agree to agree. I hope so.

All the best,

Norm

So here is some contradictory but anecdotal evidence on the topic: having now served over a decade and a half in the US military, not counting my time as a cadet, the various branches of the modern military frequently use variations of what I suspect (though have not truly researched) are derivatives of the traditional huzzah (not ay) pronunciation. The way one hears it most these days is Hoorah (“who (short pause) rah”). The Marines have their own spin: Oooh (short pause) Rah. See this article http://usmilitary.about.com/od/jointservices/a/hooah_1.htm for one study on where the modern usage comes from. I always felt intuitively that Hoorah came from Huzzah, and so I found most striking in that usmilitary article that it seems the modern use can be at least loosely traced back to the Civil War, where it was pronounced “hussah” by the Northern Army, which to me, seems a lot like “Huzzah” (not ay).

Derek,

The conclusion of the usmilitary web site’s study that the current use of Hoorah/Ooo-rah by the US Military seems to be traceable, at least loosely, to the pronunciation that was prevalent among Northern troops in the American Civil War corresponds to the information that I have been able to gather about the transition from Huzza in the 18th century to Hurrah in the 19th century. By the time of the American Civil War Hurrah (and variations thereof) seems to have been well on its way to supplanting Huzza, especially in America. Score one for Noah Webster.

For what it may (or may not) be worth, while doing research on another topic, I stumbled across another bit of documentation re: Huzzay/Huzzah in Major General William Heath’s (1737-1814) memoirs, published by himself in 1798. In the following passage from his description of the action at Lexington Green on April 19, 1775, note his spelling of “huzzaed.”

“Near Lexington meeting-house the British found the militia of that town drawn up by the road. Toward these they advanced, ordered them to disperse, huzzaed, and fired upon them; …”

SOURCE: William Heath, Memoirs of Major General Heath Containing Anecdotes, Details of Skirmishes, Battles and other Military Events during the American War, written by Himself (Boston, I. Thomas & E. t. Andrews, 1798), 12.

SOURCE: William Heath,

Excellent addition to the discussion. Thank you for continuing the pursuit.

I was not going to comment until others kept adding because I have to confess that some folks did not learn how to talk good, and used a third word. Whigs set up an elaborate trick to get GGGGG Grandpa Solomon Sparks, that “celebrated” (meaning notorious) old Tory out of his house. According to the young deceiving Whig George Parks, bragging in his old age, “He was sent down the Ya[d]kin in a Canoe. After tied hand and foot on his back he repeatedly hollowed, ‘hurra for King George.'”

Who says attitudes are not inherited?

And last week I learned that David Dellinger of the Chicago 7 is a cousin, one of the North Carolina Dellingers like the two who signed the Tryon “Association” in 1775.

Is it the genes or the family attitudes?

Dear Mr. Fuss,

I am grateful for the voluminous amount of textual information that you have provided. Well done. I, too, am convinced by the preponderance of evidence you have provided (and things I have encountered, somewhat “accidentally,” in mine own research) that the long “a” sound appears to be the most common pronunciation.

Further, I think you need not shrink from using written sources for general research. The 20th-century practice determining literacy by signatures is being exposed as a flawed methodology, for it fails to disaggregate the skills of reading and writing as they would have been understood prior to the mid 19th-Century.

This is effectively argued by Margaret Ferguson in her award-winning social-history work, “Dido’s Daughters: Literacy, Gender, and Empire in Early Modern England and France. [Note, in particular, pp. 73-81.] Literacy rates in early America were seemingly much higher than a previous generation of scholars – perhaps self-congratulating scholars, for their belief of being of a “higher” race than their forbears – was willing (or able) to allow. As better scholarship (like Ferguson’s) continues to be brought to bear on these topics, it is clear that reserving written sources as the exclusive domain of a privileged minority in 18th-Century England and her colonies is, or should be, a dying methodology.

Additionally, numerous accounts abound of written sources being read aloud to a group by one person who read well. Likewise, someone may learn to read within a group context. For instance, in my trade (shoemaking) it was not unknown that an apprentice would learn to read, in part, by reading aloud to the journeymen (adult men and women shoemakers) in the shop. I have not conducted a systematic study of this; but there is an excellent article by Bridget Keegan called “Cobbling Verse: Shoemaker Poets of the Long Eighteenth Century. (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2001) which touches on the propensity of shoemakers to publish poetry in the 18th-Century. [We’ll forgive her incorrect attribution of the word “cobbling” the the Gentle Craft of shoemaking on the basis of the rest of the article’s strength.] In it she mentions other trades, such as weavers, who also were prolific poets. It will be a pretty day in our discipline when we cease viewing literacy as something out of reach with the common man. So, there are too many reasons available with which to contend that written sources citing the “ay” ending were accessible to most, if not all, persons of the time to simply lay these aside as credible research.

In conclusion, I am of a similar belief that portraying something singular as commonplace rather than common as commonplace can and will be confusing in the limited interactions we have with the public (who very often come to us with limited conceptions and mistaken presuppositions of the 18th-Century). Too much of my daily work is spent correcting poor (read, not contextual) use of period evidences for me to ignore the far-reaching implications of “runaway interpretations.” The monkey-say, monkey-repeat (without checking sources) phenomenon is all too vibrant in living history circles. I commend your zeal in trying to bring a corrective counter-point to the discussion; and like you, I hope it will stimulate rather than stifle good research.

Be it therefore resolved, then, that I shall continue to say ‘Huzzay’ to your efforts and shall always use this pronunciation in the future as my general cheer – viz., for holidays, celebrations, birthdays, ship’s arrivals, barn-raisings, when I drop into bed at the end of a long Tidewater summer day (like I need to do now), christenings, toasts, cricket matches, horse races, &c., &c., &c. [Pronounced, et-ceteray, not et-ceterahhhhh, like the King of Siam…just kidding! : ) ] Thank you again, Sir, and well done. I remain,

Yr. Humbly Oblig’d Srvnt., &c.,

Brett,

I had not explored to any depth the relationship between written material and oral expression, other than to note, almost in passing, that some of the rhyming material that I had located was attributed to common folks (e.g. sailors) who might have been illiterate. But it certainly makes sense, with the known prevalence of reading aloud well into the nineteenth century, that even persons of limited formal education would have had ample opportunities to be exposed to all sorts of written material, and that, consequently, the differences in pronunciation between the more educated and the less educated was less pronounced that some might suppose. The recent research into literacy rates and the diffusion of learning to “the masses” by means other than formal education that you cite provides persuasive support for a strong congruence between the pronunciations heard in the drawing rooms and dining salons of the educated classes (as revealed in their writings) and the pronunciations of the common folks as heard in the streets and taverns.

Thank you for sharing it.