An armed conflict between British Regulars and armed Colonials prior to 1775? Oh yes, yes indeed. In fact this conflict raged for several months between 1765 and 1766, all along the Western Pennsylvania frontier (what is now Franklin County). It resulted in the wounding of one civilian, dozens of horses slain, wagons destroyed, money lost, hundreds of shots exchanged, and, by god, the rum was missing! Why is the rum always missing? Darn indecent, I say.

While rebellions are just tons of fun (as long as the people we like win), this particular tale has been taken way, way out of context by those who really want to romanticize it. It is called the ‘James Smith Rebellion’ (or the ‘Black Boys Rebellion’), but it wasn’t a politically-motivated rebellion against Great Britain; this is actually a bizarre tale of mob riots and vigilantism. That it involved British Regulars rather than militia seems to have been coincidental. So by this point, you may be asking, ‘How could anyone confuse these events for a rebellion against the British empire?’

The incident was largely ignored for 138 years, allowing it to become a prime target for political opportunists. During the conflict nothing was really published about it (it was a localized matter). The events were publicized when James Smith wrote his memoirs in 1799, but then basically nothing exists in print until a (highly embellished) book was written describing the riots as ‘the first armed uprising against Royal troops in the colonies’, by Neil Harmon Swanson.[1] A few years later, Swanson’s story was made into a major motion picture, Allegheny Uprising (1939), starring none other than John Wayne. Using Swanson’s claims as a source, the opening sequence tells the viewer that the men were fighting for ‘Liberty’ and the original trailer for the movie says these ‘heroes…struck the first blow for independence!’

But this should not be construed as one of those sensationalistic ‘first shots of the American Revolution!’ stories, nor used as modern political fodder (which seems to be all the rage lately). Not much of it was glorious; some bad stuff happened for some pretty woeful reasons (not that there are any good reasons to do bad things), and none of it was politically set against the government—British or Provincial. In order to prove this, I need to lay out some historical background.

Pennsylvania (especially Western Pennsylvania) was a main theater of war during the Colonial Period. The French controlled parts of the state and that simply was unacceptable to the British (this author can only assume the French taunted the British at least one time, maybe a second time, and words about fathers and elderberries were exchanged—so it was on).

In 1755, mainly because Chuck Norris wasn’t born yet, General Edward Braddock was put in charge of securing the region of Western Pennsylvania for the British. He suffered a terrible defeat at Fort Duquesne at the hands of the French and Indians, which effectively diminished any military control of the Pennsylvania wilderness that the British held during the period. Raiding parties became a standard part of frontier life—Indians bent on stopping settlement moved in as far as Northampton County, Pennsylvania, pillaging, murdering, and burning homesteads, crops, and livestock.[2] Several militia companies were raised and sent north and west to try to salvage whatever they could and defend the frontier as best as possible; Benjamin Franklin even made a trip to Easton to design and establish fortifications on the Northern edge of the Blue Mountains.[3] In the far west of Pennsylvania, the settlers had to move inward to Lancaster and further east, some even traveling to Philadelphia to escape the wanton destruction.

And at the same time, they were trying their damnedest to keep the peace with the Indians. After all, if the Indians don’t feel slighted by you, they probably won’t want to stab you in the face. It seemed like a solid plan (though we won’t get into that pesky inconsistency of the scalp bounty). The easiest way to keep peace was to try to reestablish trade (which had been stopped due to all the warring and whatnot). In 1763 trade was resumed so long as no one sought to sell guns and ammunition to the Indians. The license to sell these goods had to come directly from the governor and Penn was pretty adamant about this particular issue, due to the high volume of illegal trading that was happening.

Skipping ahead, we get to where the crap hits the fan. In March of 1765, a firm in Philadelphia sent some £30,000 of goods to Fort Pitt, some for use of the army under contract, the rest to be stored there and then sent west to the Indians when trade officially reopened. The settlers on the frontier were aware of illegal trading and grew suspicious of all goods flowing through their region. Hearing news of caravans stocked with goods from Philadelphia—and assuming that they contained firearms, lead rounds, and black powder—a group of three dozen or so armed men, along with a local official, William Duffield, stopped the traders and demanded they stay put until evidence could be brought forth which proved they were carrying property of the Crown; a completely justifiable request.

The traders refused and pressed onward. A few days later the caravan was again harassed by a separate group of men, this time demanding to inspect the goods. Reluctantly, the traders agreed. No illegal contraband was discovered and they were allowed to continue to Fort Pitt.[5]

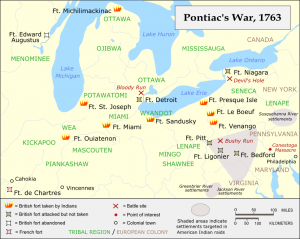

If it stopped there, then one might perhaps be more inclined to see the settlers’ actions as justifiable. But that wouldn’t be the end of it (thankfully, because what else would I write about?). You see, James Smith, a former-Indian-captive-turned-militia-Captain (during Pontiac’s War) had heard of this caravan. Despite the fact that local magistrates had checked the cargo and found it acceptable, Smith decided to gather a few of his old militia buddies and raid it; they painted their faces with soot and ash, dressed like Indians, and attacked the caravan. Some 63 wagon loads of goods were burned and a few horses were shot (but the rum was saved). Well, that escalated quickly.

The leader of the caravan, Ralph Nailer, went swiftly to Fort Loudon and asked for assistance dealing with Smith’s men whom he viewed, for obvious reasons, as highwaymen and bandits.[6] Lieutenant Charles Grant, commander of the post at Fort Loudon, sent a detachment of the 42nd Royal Highland Regiment (The Black Watch)—who were stationed there and who had performed valiantly at the Battle of Bushy Run just a few years prior—to recover the goods that had not been destroyed and to bring the attackers to justice.[7]

On their way to the place where the caravan was ransacked—known as Sideling Hill—they captured two individuals. Upon reaching their destination, they were approached by Smith’s band of ‘Black Boys’ (as they were called because of their blackened faces), who demanded that the Highlanders, led by Sergeant McGlashan, release their prisoners. McGlashan was no slouch—he prepared his men to use force if Smith and his group became threatening—and the Black Boys wisely chose to give ground, but not before McGlashan arrested a few more and confiscated some of their firearms.[8]

In spite of all this, Governor Penn still sided with the settlers. He wished that they had gone about things in a legal manner, and wrote in a personal letter that he would have stopped the caravan had the settlers made him aware of the problem.[9] But despite their transgressions he did not call up Regular troops to put them down. He saw this as a local matter, isolated. But that would all change in a month’s time, when Smith and a larger body of men (150 or so, some of them armed) approached Fort Loudon and charged Lieutenant Grant to release the prisoners or they would fire on the Fort. They also captured any British soldier attempting to leave or enter. Under duress, Grant agreed to give up his prisoners but refused to hand over their confiscated firearms (because who wants a group of vigilante bandits running around with weapons?).

Let me reiterate that the provincial government and the British, up to this point, were on the side of the settlers. Smith’s men could have let it go then and written to their representatives in the General Assembly; there is plenty of evidence that their concerns would have been heard and they could have had the illegal trading issue resolved. Instead, because violence solves everything (I guess), Smith and 20 or so of his supporters chose to take matters into their own hands.

Lt. Grant had no reason to trust Smith, which seems to have been the primary reason he did not return the firearms. After all, Smith and his band had proven that they would use their weapons to disturb the peace. During one incident, Smith’s Black Boys took it upon themselves to raid a group of grazing horses belonging to a different trade caravan right outside Fort Loudon, killing most of them and tying up and flogging the riders and tradesmen that were with them. They destroyed some of the wares before withdrawing when Grant sent a detachment of soldiers out to deal with them. The soldiers were ordered to follow the Black Boys and, upon realizing this, the Black Boys opened fire on the Highlanders. The Black Watch soldiers returned fire resulting in the wounding of one of Smith’s men.

Following this skirmish, Smith marched on Fort Loudon again, making more demands of the British officer and his men, specifically that they be permitted to inspect all the goods remaining from their attack on the grazing horses. When Grant denied this, Smith and some local magistrates took it upon themselves to continue inspecting all goods moving throughout the region, handing out passes to tradesmen once they found them to contain legal or personal belongings (but no firearms, powder, or ammunition seems to have been transferred to the Fort).[10]

A few days after Smith surrounded Fort Loudon a second time, Lieutenant Grant was out riding on his horse with two others when Smith and four Black Boys ambushed him (because they like throwing cats amongst the pigeons). They shot at him or his horse (Grant didn’t know) which caused the steed to buck him. They took Grant prisoner and told him that they would bring him south if he didn’t return the guns he had taken from them (Grant had apparently forgotten to call ‘no backsies’). He told them that if they released him he would return the weapons shortly and his captors complied, letting him return to the Fort.[11]

But Grant lied; he had no intention of returning the guns. So an advertisement soliciting additional support for the Black Boys appeared. The advertisement stated plainly:

“These are to give notice to all our Loyal Volunteers, to those that has not yet enlisted, you are to come to our Town and come to our Tavern and fill your Bellys with Liquor and your Mouth full of swearing and you will have your pass, but if not your back must be whipt and your mouth be gagged; you need not be discouraged at our last disappointment, for our Justice did not get the Goods in their hands as they expected, or we should all have a large Bounty. But our Justice has wrote to the Governor, and everything clear on our side and we will have Grant, the Officer of Loudon, Whip’d or Hang’d, and then we will have orders for the Goods, so we need not stop; what we have a mind and will do for the Governor will pardon our crimes, and the Clergy will give us absolution, and the Country will stand by us, so we may do what we please for we have Law and Government in our hands & we have a large sum of money raised for our support, but we must take care that it will be spent in our Town, for our Justice gives us, and those that have a mind to join us, free toleration for drinking, swearing, Sabbath breaking and any outrage which we have a mind to do, to let those Strangers know their place.”[12]

Whatever support they had from Philadelphia was gone with the publication of this advertisement (which was posted around Fort Loudon). John Penn was furious when he discovered that his name and title were being used in such an abusive manner—in no way had he supported the illegal activities of James Smith and it had only been his empathy towards the situation of the frontier settlers that stayed his hand from bringing them to justice.[13] But that sympathetic feeling soured when he read the note from General Gage, the military commander in chief, which he received with a copy of the advertisement. He wrote back to Gage that he would do his utmost to arrest all those who had wronged the troops and that if he had to he would bring in more Regular troops to subdue the riots.

It must be remembered that at this point trade had been stunted due to these actions, putting the settlers in more danger (and they didn’t even know it). The Indians were in need of goods and if the British did not fulfil their trade duties the Indians would return to trading with the French (which would mean free trade of guns and ammunition—the very thing which the settlers were trying to prevent). General Gage and Governor Penn, looking at the larger picture, saw the impediment of trade in the region as something that could lead to even more dangers and possibly the start of yet another war.

In a few weeks (June 6, 1765) the trade agreement with the Indians would be opened completely, with no licenses required. In the widely-published announcement of the resumption of trade, Penn made a note that the inspection of trade goods going west must stop, or he would be forced to call in troops to end it. Smith seems to have gotten the hint; he and the Black Boys would no longer harass any of the caravans that moved into Cumberland County. There was no longer a legitimate legal basis for the Smith Rebellion, but hostilities did not end.

Angry that Grant had not yet returned the guns, Smith and hundreds of ruffians (which he called the Sideling Volunteers) surrounded Fort Loudon again and besieged it. As before, Grant refused their demands.[14] Dozens of rounds were fired into the fort by Smith’s men.[15] Grant could not maintain his stronghold—the British Regulars ran out of ammunition and were forced to surrender the arms they had taken. They were given to one of the Justices of the Peace who was under strict orders to dispose of them in a manner given by Governor Penn (they were not, as far as I can tell, given back to their original owners). The Black Watch troops were then ordered to evacuate Fort Loudon and sent instead to Fort Bedford where they would finish out their tour.

For a while the Black Boys ceased all riots and hostilities, but in 1768 when Frederick Stump was arrested for the brutal murder of several Indians, a group taking the name of the Black Boys (with painted faces and all) once more rioted and forced—at the muzzle of a gun—his release. This attack, along with the atrocious way they treated the troops (who were there to defend the province at the behest of the settlers themselves) sticks an arrow into the mythic notion that the Black Boys were firing the first shots of the Revolution.[16] Liberty, independence, and politics were the last thing on the minds of Smith and his compatriots. Instead, what started as a harmless inspection of trade goods in order to keep the frontier counties safe turned into a vicious rabble bent on harassing and threatening outsiders. For the settlers, it may have appeared as though they were doing something just and right, but in truth they were doing more harm than good. And Smith’s shortsighted actions could have cost the region a lot more than it did had the riots continued.

So what can be concluded? Was the first ‘blow for independence’ struck by James Smith and the Black Boys? Of course not. Independence was not even an issue at the time. And as Eleanor Weber points out, the frontier counties behind these illegal attacks were actually well represented in the General Assembly (which was why their grievances were heard and dealt with so swiftly by Governor Penn when he first took office).[17] Smith’s error was that he took the momentum and support he had built with his first attack on the original trade caravan—which some would say was justifiable albeit unnecessary—and went wild. Smith realized this later in his life and wrote, “The King’s troops and our party had now got entirely out of the channel of the civil law, and many unjustifiable things were done by both parties. This convinced me more than ever I had been before, of the absolute necessity of civil law, in order to govern mankind.”[18]

[1] The First Rebel (Farrar and Rinehart, Inc.: New York, 1937), 207-218.

[2] Incidentally, in October of 1755, 100 Delaware and Shawnee attacked the Scotch-Irish settlements of Franklin and Fulton Counties (at this point all part of Cumberland County, the area where James Smith was born and lived, and where these events took place); they killed or captured 47 out of 93 people and nearly destroyed the whole region before moving into Northampton County the following month (See Pennsylvania Archives Ser. 1, Vol. 2, 462 for a full account of the massacre).

[3] “I make bold to trouble you once more, and it is not unlikely that it may be the last time. The Settlers on this side of the Mountain all along the River side are actually removed and we are now the Frontier of this part of the Country.” Letter from William Parsons to James Hamilton and Benjamin Franklin, 15 December, 1755. Accessed March 10, 2014: http://founders.archives.gov/documents/Franklin/01-06-02-0129.

[4] For the full list of grievances, see Eleanor M. Webster, ‘Insurrection at Fort Loudon in 1765, Rebellion or Preservation of the Peace?’, Western Pennsylvania History Magazine 47 (April 1964), 137. For more on the tradition of scalping and scalp bounties in Pennsylvania, see Henry J. Young, ‘A Note on Scalp Bounties in Pennsylvania‘, Pennsylvania History Vol. 24, No. 3 (July, 1957).

[5] Webster, ‘Insurrection at Fort Loudon in 1765’, 130, n.30.

[6] Nailer’s account appears in Pennsylvania Archives Ser. 1, Vol. 4, 225.

[7] It did not help matters that the detachment from the Black Watch were paid by the traders for properly securing the goods.

[8] See Sergeant McGlashan’s account of the events in Pennsylvania Archives Ser. 1, Vol. 4, 234-236. The rum is missing here; he states that he found “a few horse loads of rum untouched” at the scene of the Sideling Hill caravan; other accounts from Smith state that they left all the rum untouched (amounting to 18 loads). So why is the rum gone?

[9] Webster, ‘Insurrection at Fort Loudon in 1765’, 131, n.39. It also seems as though Grant believed this to be the case, writing to General Gage that “I fear the Governor may be too apt to listen to [the magistrates in league with James Smith] false Assertions, as a number of the Magistrates of the County have lately drawn up a Remonstrance or Something of that Kind to the Governor, in a private manner, in which I have great Reason to believe they have endeavour’d to thro the Blame off themselves and their people, & fix it Upon me & the Garrison I Command.” (Pennsylvania Archives Ser. 1, Vol. 4, 231).

[10] See examples in Pennsylvania Archives Ser. 1, Vol. 4, 220, 224-225.

[11] See Grant’s account in Pennsylvania Archives Ser. 1, Vol. 4, 220-222.

[12] The full letter with copies related to this and other events, including the advertisement, and correspondence between John Penn, General Gage, and others, can be found in Pennsylvania Archives, Colonial Records, Vol. 9, 267-276, 281, 292-293, 297, 300-304; spc. 271 for the advertisement. A quick side note; many people believe this advertisement to have been written by someone unsympathetic to Smith and the Black Boys—whether it was the British or just someone who sided with them, we don’t know.

[13] Penn wrote, “The Advertisement you did me the honour to inclose me is a very extraordinary one. The insinuations in it, that the Conduct of those lawless people is countenanced & abetted by me, are Villanously false & scandalous, and most injurious to my Reputation. I shall spare no pains in detecting the Authors of it, but I cannot help suspecting that it takes its rise from a party in this province, who have been indefatigable in their endeavors to malign and traduce me on all occasions.” (Pennsylvania Archives, Colonial Records, Vol. 9, 276)

[14] Contrary to popular belief, guns were priceless on the frontier because so few people seemed to have possessed them. According to multiple accounts during Indian attacks, the frontier communities of Pennsylvania were indefensible because no arms could be found in any sufficient quality or quantity. One report from York in 1755 notes that “the inhabitants here in the greatest confusion, the principal of whom have met sundry times, and on examination find that many of us have neither arms nor ammunition” and “it is probable before this comes to hand part of these back counties may be destroyed. We believe there are men enough willing to bear arms and go out against the enemy were they supplied with arms ammunition and a reasonable allowance for their time, but without this at least arms and ammunition we fear little of purpose can be done.” (Pennsylvania Archives Ser. 1, Vol. 2, 448); Peter Silver, in Our Savage Neighbors: How Indian War Transformed Early America (New York: Norton, 2008), noted the correspondence between Colonel James Burd to William Allen in 1763, in which he recounts: “I collected the men of town [of Northampton] together…but found only four Guns in the Town.” Two of the guns found were broken and unusable. For more on the limited quantity of arms and ammunition along the Pennsylvania frontier, see also Pennsylvania Archives Ser. 1, Vol 2, 433; 450; 455; 461, wherein George Stevenson wrote to the Secretary of the Province, “for God’s sake either…send us Arms, Ammunition, & Blankets…or else our Country shall be deserted”; 463; 465; 475.

[15] General Gage wrote to Governor Penn, “If the King’s Troops are fired upon, and his Forts threatened with Assaults by Men in Arms, headed by Magistrates, who refuse the ordinary Course of justice demanded of them by the Officers, I can’t pretend to answer for the Consequences.” (Pennsylvania Archives, Colonial Records, Vol. 9, 268). So the avid reader may be wondering why Grant did not return fire. Well, since James Smith and his Black Boys had been so effective at inspecting goods moving to and from the Fort, supplies of gunpowder and ammunition did not make it in, though the Highlanders seem to have had plenty of rum if the writs given by Smith are any indication.

[16] Patrick Griffin writes about this issue and notes that among the slain Indians were women and children; he asserts that the people of the frontier were so prejudiced against Indians that regardless of the brutality and barbarity of the crime, no jury would convict settlers. This is also true of the Black Boys under the command of James Smith. See his American Leviathan: Empire, Nation, and Revolutionary Frontier (Macmillan: New York, 2007), 80-84.

[17] Webster, ‘Insurrection at Fort Loudon in 1765’, 137.

[18] James Smith, An Account of the Remarkable Occurrences in the Life and Travels of Colonel James Smith (John Bradford: n.a., 1799), 110-111.

5 Comments

I need to thank the good people of the Pennsylvania State Archives, and also Patrick Spero, for letting me bounce my research off of them and offering some useful advice in the process.

Unlike Thomas Verenna, Patrick Spero’s book, Frontier Rebels, calls the Black Boy’s uprising a rebellion against the British Government and suggest it is a contributing cause to the American Revolution.

Verenna’s views seem more reasonable than Spero’s.

thank you for posting this interesting article about a “moment” in our American History. I love American History, and seem never to get enough of it. Before I searched info about the true Allegheny Uprising, I never knew there was a new called “Journal of the American Revolution.” I look forward to reading more. Thank you again.

Glad you liked it! Sorry so late in getting back to your comment!

Thomas Verenna, thanks for sharing your opinions on the Black Boys Revolt. I am a direct descendant of Thomas and Janet Hutchison Barr’s son Robert Barr 1748-1778. The Barr cabin was the area that the Black Boys and the 42nd Highlanders shot at each other and James Brown was wounded. My understanding is the Highlanders found James at the stream washing himself. They discovered black behind his ears and was going to arrest him. The Black Boys convinced the Highlanders to release him with his rifle. It should be noted that most of the Black Boys were Scot-Irish from Londonderry, Northern Ireland and the Highlanders were very likely distant cousins.

The 3 Barr boys were young teens in 1765-66 but Col. James Smith was a close neighbor and later they all ended up as early settlers in Derry Twp. Westmoreland Co. PA obtaining land titles 3 April 1769. They had been considered squatters. Their sisters married 2 of the original settlers John Pomeroy and James Wilson. Why did so many leave the ‘Conocochegue Settlement to homestead the wilds of Westmoreland Co.? Were they forced to leave because of their association with the Black Boys and their events? Interestingly Robert Barr’s younger brother James Barr, Esq. and Col. James Smith represented PA at the 2nd Continental Congress in 1787 to approve the Constitution. These families were members of the Mercersburg Presbyterian Church and many of the children’s baptisms and marriage records are recorded there.

Interesting to note that most of these early Westmoreland County pioneers would return to the Conococheague Settlement to spend the winter with their families.