Myth:

“The fate of a nation was riding that night,” Longfellow wrote. Fortunately, a heroic rider from Boston woke up the sleepy-eyed farmers just in time. Thanks to Revere, the farmers grabbed their muskets and the American Revolution was underway: “And the spark struck out by that steed, in his flight, / Kindled the land into flame with its heat.”

Busted:

In a previous column, I highlighted the elaborate communications network that included Paul Revere and many others. Now I wish to point out that those farmers were not so sleepy-eyed after all and that a spark had already kindled the fire of revolution several months before. Here’s the best part: Revere himself bears testimony to the revolution that had swept through Massachusetts the previous year. Without Revere’s several rides that predated the one Henry Wadsworth Longfellow chose to celebrate, and without the revolution these rides helped to spark, Paul Revere would have had no occasion to mount a horse 239 years ago this evening, “A hurry of hoofs in a village-street, / A shape in the moonlight, a bulk in the dark,” with his “cry of alarm/ To every Middlesex village and farm.”[i]

***

News of the Tea Party: December 17, 1773.

The day after patriots brewed tea in the Boston Harbor, Paul Revere rode express to New York and Philadelphia to spread the news. Time was of the essence. The East India Company had sent shipments of tea to those destinations as well, and also to Charleston, South Carolina. For the radical action in Boston to influence events elsewhere, news had to arrive before the tea. If patriots in other cities learned of Boston’s dramatic response, they could brew their own ports of tea. Or perhaps they wouldn’t have to: by threatening to imitate Boston, they could induce the ship owners, consignees, and port officials to send the shipments back to London, unloaded.

Headed toward New York was the hefty ship Nancy bearing 211,778 pounds of tea — over twice the total amount on all four vessels sent to Boston. New York patriots had induced the consignees to give up their interest in the cargo, but Governor William Tryon placed the man-of-war Swan at the entrance to the harbor and vowed to take charge of the tea. Patriots and the Governor stood at an impasse — until the evening of December 21, when Revere arrived in town with news of Boston’s bold action. This tipped the balance. According to British General Frederick Haldimand, the news “created such a ferment” that Tryon backed off. Fearing “dangerous extremities,” the Governor announced he would allow the tea-laden ship to return to London with its cargo untouched, just as the patriots demanded.[ii]

Headed toward Philadelphia was the ship Polly, also loaded with over twice the amount of tea sent to Boston. There, as in New York, patriots had already cajoled the consignees to give up their interest in the cargo. Through the month of December, day-by-day, they waited for the Polly to arrive, but before it did, on Christmas Eve, the people of Philadelphia received Revere’s dramatic dispatch from Boston, which was greeted “with the ringing of bells, and every sign of joy and universal approbation.” The very next evening, on Christmas, the Polly was sighted twenty miles down the Delaware River at Chester, and the day after that, patriots escorted the ship’s captain, Samuel Ayres, into Philadelphia and showed him broadsides posted about town from the “Committee of Tarring and Feathering,” warning Ayres of “the pitch and feathers that are prepared for you.” The captain certainly got the message, and in case he didn’t, some 8,000 people gathered outside the State House the next day and promised to replicate the event in Boston unless Ayres piloted his ship from the harbor immediately. Less than two days after his arrival, Captain Ayres, his crew, and the Polly, still loaded with tea, were on their way back to London.[iii]

Boston Port Act and the Continental Congress: May 14, 1774.

Parliament responded to the destruction of tea by closing the port of Boston. Immediately upon hearing that news, the Boston Committee of Correspondence dispatched Revere once again. Leaving Boston on May 13, Revere carried a circular letter to Connecticut, New York, New Jersey, Philadelphia, and “Colonies to the Southward of them,” along with a copy of the Boston Port Act, the resolves of Boston’s emergency town meeting, and a letter, aimed primarily at merchants, calling for a suspension of “your Trade with Great Britain.”[iv] The prime target was Philadelphia, the hub of trans-Atlantic trade; unless merchants there signed on, any boycott would not work. That city rejected the call for another round of trade warfare, but in a compromise move, on May 21, its Committee of Correspondence called for “a general Congress of Deputies from the different Colonies, clearly to state what we conceive our rights and to make claim or petition of them to his Majesty, in firm, but decent and dutiful terms.” New York, another critical port, arrived at the same decision two days later, and other locales, upon hearing the news Revere was spreading, responded in similar terms. So was born the First Continental Congress.[v]

Suffolk Resolves and the revolution in Massachusetts: September and October, 1774.

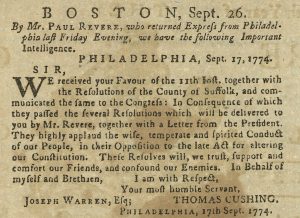

Shortly after its Boston Port Act, Parliament passed the Massachusetts Government Act, which disenfranchised the citizenry of the entire colony. This provoked such outrage that every county in Massachusetts closed its courts and rejected British rule, unless or until the act was repealed. Every county but one, that is. In Suffolk, whose “shiretown” was Boston, British law remained buttressed by British troops. But while other counties walked the walk, Suffolk talked the talk. Its protest of the Massachusetts Government Act was better written than similar documents penned by other counties, and it was the “Suffolk Resolves” that Paul Revere carried with him on September 11, headed toward Philadelphia.

When Revere arrived on September 16, the Continental Congress had been meeting for twelve days. Debates revealed a split between radicals and moderates, but Revere’s news of the revolution underway in Massachusetts tilted the scales. The next day Congress unanimously endorsed the Suffolk Resolves, with even moderates like Joseph Galloway forced to vote in favor. “This was one of the happiest days of my life,” John Adams noted in his diary. “In Congress we had generous, noble sentiments, and manly eloquence. This day convinced me that America will support the Massachusetts or perish with her.”[vi]

At this juncture communication between Massachusetts, at the forefront of resistance, and the Continental Congress, the inter-colony center of deliberations, was critical. Revere returned to Boston with several letters from delegates, and on September 29 he embarked on another round trip to and from Philadelphia, carrying letters both ways. At issue was how far, and how fast, Massachusetts could proceed without jeopardizing support from other colonies. Massachusetts radicals from the interior wanted to abandon the 1691 Charter, with its Crown appointed governor, while easterners, including the Boston leadership, favored a more moderate approach. When Joseph Warren asked Samuel Adams for advice, Adams wrote back: slow the Massachusetts revolution down, he said, or it will alienate important allies.[vii] “Independency” and “setting up a new form of government of our own” were ideas that “startle people” in Congress, John Adams wrote in letters carried by Revere.[viii] Due in part to these sorts of communiqués, the Massachusetts Provincial Congress succeeded in tempering country radicals, who wanted to attack British troops in Boston and declare independence.

Portsmouth: December 12, 1774

Through the fall and into the winter, Revere and a group of patriots, “chiefly mechanics” he later wrote, kept a watchful eye on British movements. In the second week of December, these men got wind that the British warship HMS Somerset was headed to Portsmouth’s Fort William and Mary to protect its large stockpile of muskets, artillery, and powder. Simultaneously, the Boston Gazette published news of an executive order to prohibit the exportation of all arms and ammunition to the rebellious colonies in America.[ix] If that vessel arrived and secured the fort, and if no additional weaponry could be imported into the colonies, poorly armed patriots would be hard pressed to face off against Regulars, should it came to that. But if Portsmouth patriots received this news in time, they would be able to capture the fort and its munitions, currently under the guard of only six soldiers. Enter Paul Revere, who embarked over icy roads rarely traveled under such conditions. In terms of physical danger, it was certainly his most treacherous ride.[x]

After hearing Revere’s news, Portsmouth patriots did in fact seize a hefty store of weaponry and powder, some of which would later come into play at Bunker Hill. Whereas militiamen throughout Massachusetts had overturned authority three months earlier, those confrontations had not featured armed men facing off against each other. This one did, and the colonials won. The British loss at Portsmouth practically guaranteed that the King’s forces would strike back. The only questions were where and when.

Lexington and Concord: April 8, 16, and 18, 1775.

First question: where? British spies reported that patriots were securing arms and powder primarily in two locations, Worcester and Concord, but that to attack Worcester, the heart of resistance in the interior, would be foolish.[xi] This was obvious to patriots as well. Folks knew that the military governor, General Thomas Gage, could not sit idly by as his own soldiers called him “old woman” and officials back in London demanded results. He must strike somewhere, and Concord was by far the most likely target. From Concord, where the Provincial Congress was sitting, James Warren wrote to his wife Mercy Otis Warren on April 6: “This town is full of cannon, ammunition, stores, etc., and the [British] Army long for them and they want nothing but strength to induce an attempt on them. The people are ready and determine to defend this country inch by inch.”[xii]

Second question: when? It could have been anytime, but when news hit Boston on April 2 that four regiments from Ireland were headed their way, along with two thousand seamen and “a proper number of frigates” to patrol the New England coast, Paul Revere, his intelligence-gathering group of mechanics, Joseph Warren and the Boston Committee of Correspondence, and indeed the whole town of Boston shifted to red alert.[xiii] With a greater force at his command, Gage would likely strike soon. Bostonians started evacuating en masse, not wishing to be stuck behind British lines once fighting broke out in a day or two or ten or twenty.[xiv]

On April 7 Warren, Revere, and others noted excessive British movements in Boston’s harbor, which they thought were preparations for the expected assault on Concord. The next day Revere rode to Concord with the news. Although no Regulars attacked just then, this alarm served a greater purpose: patriots in Concord hastened to move their stores out of town, where they would be difficult for British troops to find.

A week passed, more time yet for patriots to prepare. On the morning of April 16, Paul Revere made a second ride westward, to Lexington this time to confer with Samuel Adams and John Hancock about how to respond to Gage’s immanent attack. On his way back to Boston, he met with patriot committees in Cambridge and Charleston. There, he helped fine-tune an intelligence and communication network that had been in place since March 14, when the Provincial Congress’s Committee of Safety resolved that “watches be kept constantly at places where the provincial magazines are kept” and that Charlestown, Cambridge, and Roxbury – the towns surrounding Boston – “procure at least two men for a watch every night, to be placed in each of these towns,” and that they “be in readiness to send couriers forward to the towns were the magazines are placed, when sallies are made from the army by night.”[xv]

Two nights later, on April 18, this network would be set in motion. What we now refer to as “Paul Revere’s Ride” was of great historical import, but because the countryside was already primed, and because the alarm traveled in so many ways, Revere’s singular contribution that night was probably less critical than on some of his other rides. This is not to belittle the importance of the Lexington alarm and the onset of military conflict, but only to observe that Revere’s personal adventures, including his capture by British officers that he emphasized in the first account of his experiences that night, were dwarfed by so much else of consequence that happened during the Regulars’ advance.[xvi] It is little wonder that his now-celebrated ride was treated as no more than an anecdote, one among thousands of tales that thrived in American lore until Longfellow’s poem, nearly a century later, went viral.

After Lexington and Concord, the need for communications continued. From April 20 to May 7 Revere was on the road again, helping to coordinate affairs for an army-in-the-making. That fall he traveled to Philadelphia to study the manufacture of gunpowder, critical to the American cause. It had been a busy two years for American revolutionaries, and Paul Revere was right at the hub of it.

So let’s toast the revered horseman’s praises tonight, but let’s also realize he was not a one-trick, one-trip pony. Many times, and on many horses, did he ride. His mission: to connect people and groups. To succeed, a revolution requires careful coordination among various organizations with different perspectives and agendas. That can only happen if people communicate with each other, and in those days, missives were carried either by ship or by horse. Revere made use of the latter, more versatile and less vulnerable. His “hurry of hoofs” are with us to this day, and justly so.

[i] A summary list of Revere’s other rides appears in David Hackett Fischer, Paul Revere’s Ride (New York: Oxford University Press, 1994), 299-300, with documentation on 300, 381, and 385-86. In addition to the rides discussed here, Fischer includes a fleeting reference to a journey to Exeter, New Hampshire, on January 26, for “liaison with N.H. Congress.” The Massachusetts Provincial Congress, in recess at that time, placed a high priority on preparations for war in other New England colonies.

[ii] Haldimand to Lord Dartmouth, December 28, 1773, quoted in Benjamin W. Labaree, The Boston Tea Party (New York: Oxford University Press, 1964), 155. Ironically, during all this hoopla, the Nancy was sailing away to the south, having encountered a fierce storm. To repair its damage, it pulled into Antigua instead of New York, and when it finally arrived at its destination the following spring, four months late, it turned right around and sailed back to London, much to the chagrin of its crew, many of whom tried to jump ship.

[iii] Boston Gazette, January 24, 1774; Robert Francis Oaks, “Philadelphia Merchants and the American Revolution, 1765-1776,” (PhD thesis, University of Southern California, 1970), 121-122; Francis S. Drake, ed., Tea Leaves: Being a Collection of Letters and Documents relating to the Subject of Tea to the American Colonies in the year 1773 (Boston: A. O. Crane, 1884), 365; Labaree, Boston Tea Party, 158.

[iv] The Town of Boston to the Colonies and the Committee of Correspondence of Boston to the Committee of Correspondence of Philadelphia, May 13, 1774, The Writings of Samuel Adams, Harry Alonzo Cushing, ed., (New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1904), 3:107-111.

[v] American Archives, Series 4, vol. 1, 341, 297. Philadelphia: http://lincoln.lib.niu.edu/cgi-bin/amarch/getdoc.pl?/var/lib/philologic/databases/amarch/.322

New York: http://lincoln.lib.niu.edu/cgi-bin/amarch/getdoc.pl?/var/lib/philologic/databases/amarch/.328 Fischer (299) lists this ride as terminating in Philadelphia, but on the following page he notes a receipt for reimbursement “for a journey to King’s Bridge, New York, 234 miles.” Whether Revere himself traveled all the way to Philadelphia or someone else carried on from New York is immaterial: his messages traveled “southward” in either case. Fischer also includes in his list of Revere’s rides, “Meetings with Whig leaders ‘for calling a Congress,” dated “Summer 74,” but the only documentation is a letter from Revere to Jeremy Belknap in 1798, twenty-three years later. Whether Revere was referring to his trip in May or whether he took a different trip, while certainly of interest, is not critical. The main point is that the flow of information he facilitated helped spur the Continental Congress.

[vi] John Adams’s diary entry for September 17, 1774, in Works of John Adams, Charles Francis Adams, ed., (Boston: Charles C. Little and James Brown, 1850), 2:380.

[vii] Joseph Warren to Samuel Adams, September 12, 1774, and Samuel Adams to Joseph Warren, September 24 and September 25, Richard Frothingham, The Life and Times of Joseph Warren (Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1865), 376-378.

[viii] John Adams to Joseph Palmer, September 27, 1774, and John Adams to William Tudor, October 7, 1774, Papers of John Adams, Robert J. Taylor, ed., (Cambridge: Kelknap Press, 1977-), 2:173, 187–188.

[x] Peter J. Flood, “A Week in December: Paul Revere’s Secret Mission to New Hampshire,” The Revere House Gazette, issue 114, Spring 2014; Fischer, Paul Revere’s Ride, 52-57, 381. For an array of source documents, see Charles L. Parsons, “The Capture of Fort William and Mary, December 14 and 15, 1774,” New Hampshire Historical Society Proceedings, 4 (1890–1905), 18-47. Fischer’s dating is confusing. On page 54 he has Revere leaving Boston on December 13, but on 300 he says December 12. Also on 300, Fischer has Revere returning to Boston on December 13. Flood, who favors the December 12 departure, argues from computations based on Revere’s receipt that he spent five days in Portsmouth, not just one as stated in Fischer. The argument is plausible but conjectural.

[xi] These reports are reprinted in Wroth, Province in Rebellion, documents 670–695, pages 1967–1995. Dr. Benjamin Church, one of Gage’s informants, served on the all-important Committee of Safety, which coordinated the stockpiling of armaments. See also Allen French, General Gage’s Informers (New York: Greenwood Press,1968), 3-33.

[xii] James Warren to Mercy Otis Warren, April 6, 1775, Warren-Adams Letters (Boston: Massachusetts Historical Society, 1917), 1:44-45.

[xiv] On April 4 William Tudor wrote to John Adams, “The women are terrified by the fear of blood and carnage.” (Quoted in Merrill Jensen, The Founding of a Nation: A History of the American Revolution, 1763-1776 [New York: Oxford University Press, 1968], 565-566.) Merchant John Andrews wrote on April 11: “We are all in confusion at present, the streets and Neck lin’d with waggons carrying off the effects of the inhabitants, .. imagining to themselves that they shall be liable to every evil that can be enumerated, if they tarry in town.” (“Letters of John Andrews of Boston, 1772-1776,” Massachusetts Historical Society, Proceedings, 8 [1864-1865], 402.)

[xv] William Lincoln, ed., The Journals of Each Provincial Congress of Massachusetts in 1774 and 1775, and of the Committee of Safety, with an Appendix, containing the Proceedings of the County Conventions (Boston: Dutton and Wentworth, 1838), 513.

[xvi] For Revere’s testimony on three different occasions, see Edmund S. Morgan, ed., Paul Revere’s Three Accounts of His Famous Ride (Massachusetts Historical Society, 1961). For a discussion of the difference between his account immediately following the experience and his recollection 23 years later, see Ray Raphael, Founding Myths (New York: The New Press, 2004), 13-17.

4 Comments

Very interesting morsel: Sam Adams writing “. . . slow the revolution down.” First time I’ve encountered this sentiment. I’d like to hear from others about the status and pace of “the revolution” elsewhere in the colonies in late 1774.

Adams was trying to slow down the pace of revolution only in MA at this time, fearful that MA was getting “too far ahead of the curve,” as we might say today. Elsewhere, he preferred it would speed up, but being politic, he understood that he personally was not the one to do this. This balancing act is key to understanding his role both at the Continental Congress and in MA during the pivotal months of September and October of 1774. The traditional image of Adams the rabble-rouser has preventing us from seeing that it was the MA countryside (not Boston and its leaders) that was driving the revolution forward at this moment. The Worcester town meeting actually pushed for independence (see one of my first posts), and other western MA radicals wanted to attack the Regulars in Boston. Adams understood that only if MA remained on the defense would the middle and southern colonies support it.

Thanks, Ray, this is a useful frame of reference for me. I keep in mind that Adams and the others were constrained in their work by the communications networks of the late 18th century: stagecoaches and mounted couriers. I wonder if the British would have attempted their Lexington-Concord gambit if the colonial militia had had cell phones?

So far as balancing geography and politics – that remained a required aspect of national government for quite some time. In regards to Rick’s inquiry on cellphones, I feel we can envision that much more clearly when we view contemporary events and rebellions.

Perhaps the Letters of Correspondence was indeed the social media of it’s day, Paul Revere the text message, Thomas Payne the blogger and engraving’s of Peter Fleet the photojournalist witness.