With April 19 nearing, marking the anniversary of the start of the American Revolutionary War (the official regional holiday of Patriot’s Day in New England), it seems only fitting to delve into the popular tale of the secret informant of Dr. Joseph Warren.

As the story often goes, Dr. Joseph Warren, the de facto revolutionary leader in Boston, first consulted with a secret informant on April 18, 1775, before sending Paul Revere on his most famous midnight ride ahead of a British march (which ultimately led to the first shots of the Revolution the following morning). Because of various circumstantial evidence, various historians including David Hackett Fischer have nominated as that informant Mrs. Margaret Gage, wife of the British Commander-in-Chief of North America Lt. Gen. Thomas Gage, head of the British in Boston.[1] Why Mrs. Gage? She was American born for one. She also had later expressed in a private letter her heartfelt anxiety over the Battle of Bunker Hill given her American birth but her loyalist politics and marriage to the head of the British Army in America. Furthermore, she was months later sent back to England by her general husband. However, in examining that evidence, modern historians with a keen eye have come to regard the Mrs. Gage story as myth. The best debunking of this topic comes from J. L. Bell’s series at his Boston 1775 blog. There, Bell expertly discredits the idea that Mrs. Gage was sent home to England for any reason but for her own safety. He also debunks the idea that her and Gen. Gage’s marriage suffered in the post-war years because of this incident (it did not). I fully subscribe to Mr. Bell’s interpretation that this story is a myth.[2]

I have expanded on this story one further. Was there an informant at all? Answer: I think not.

First, the only real evidence of an informant comes sometime after the events of April 19, 1775. Specifically, Jeremy Belknap, future founder of the Massachusetts Historical Society, set about interviewing people in the encampments outside Boston after the war had begun and the Boston Siege was at a stalemate. On October 25, 1775, Belknap spoke with one Mr. Waters, recording

“Mr. Waters informed me, that the design of the regular troops, when they marched out of Boston the night of April 18, was discovered to Dr. Warren by a person kept in pay for that purpose… Dr. Warren, he applied to the person who had been retained, and got intelligence of their whole design; which was to seize [Samuel] Adams and Hancock, who were at Lexington, and burn the stores at Concord. Two expresses were immediately despatched [sic] thither, who passed by the guards on the [Boston] Neck… Another messenger went over Charlestown Ferry…”[3]

Now, there are several problems with the above statement. First, two “despatches” were not sent by Boston Neck: just one, William Dawes. The other by Charlestown Ferry was Paul Revere, but he didn’t go by ferry, he slipped over the river by rowboat at night. (To be fair, Waters perhaps used “Charlestown Ferry” loosely, meaning the ferry way rather than the actual boat.) Second, Waters’s statement was made months after the fact, and we cannot be sure of his reliability. How did Waters know this information? Waters may have been citing encampment gossip, and since Dr. Warren was by then dead, the recorder Mr. Belknap would have found it difficult to corroborate the information. Additionally, as Warren was the first martyr of the Revolution, and by October already very famous, Mr. Waters, like so many others, might have simply wanted to link his story to the fame of Warren in some fashion. Finally, had this supposed informant that Mr. Waters referred to been credible, one would have expected the information to be more accurate: for the British aim was not Samuel Adams and John Hancock as many British historical documents prove (including the march orders issued by Gage). That was just the fear the Americans held! That is, if there was indeed an informant well-placed in the British Army apparatus, the same alleged informant should have known the British aim was not the two Whig leaders. Simply put: Mr. Waters’s statement sounds like an American concoction. You know, history is written by the victors.[4]

The real problem with the informant myth is that, in order to assume Dr. Warren required an informant at all is to require that Dr. Warren was ignorant of all of the many facts around him, or just plain stupid.

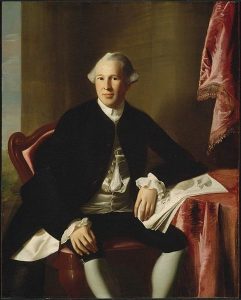

Now, Dr. Warren was a leading physician in Boston, was soon elected as President of the Massachusetts Provincial Congress, and, though he died at Bunker Hill before his commission was ready, was also selected as a Major General in the nascent Massachusetts Provincial Army. Furthermore, he was twice chosen as an orator for the Boston Massacre Anniversary, giving fiery speeches before packed crowds at Old South Meetinghouse. In other words, Dr. Warren possessed great intellect and perspective. He was not stupid.

So we are left with, if Dr. Warren required an informant, it was because he was ignorant of the many facts around him. Let us consider the facts:

- Mar 20, 1775: After British Gen. Gage receives intelligence (written Mar 9 in very bad French, perhaps disguised writing of secret British spy Dr. Benjamin Church) informing of a great deal of war stores held by the Americans in Concord, west of Boston, Gage sends three disguised scouts there to investigate. The scouts confirm the war stores in Concord, but the locals detect the British scouts, and they are forced to leave the town before danger is upon them. The incident is most certainly relayed back to Dr. Warren.[5]

- April 2: Two ships arrive in Marblehead, Massachusetts, with rumors that orders are coming from Britain ordering Gage to aggressive action. Many Bostonians rush to pack and depart the city ahead of this doomsday, including Samuel Adams and John Hancock, who retire to Lexington on April 7.[6]

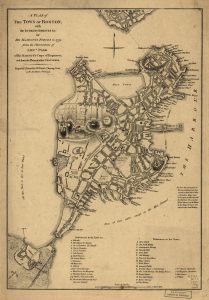

- April 8: Though the British Navy around Boston were already taking advantage of the spring thaw to accomplish much needed repairs to the warships, when they begin hauling up the longboats onto the ship decks to make repairs, it sends fear through Boston. Worried the British would march out on the coming Sabbath while the countryfolk were in church, Paul Revere and Dr. Warren confer, then agree that Revere will warn Hancock and Adams. On Saturday, April 8, Revere mounts his horse and gallops for Concord. It was a false alarm.[7]

- April 14: HMS Nautilus arrives in Boston Harbor carrying with her the “secret” instructions from Lord Dartmouth, the same “secret” instructions that Boston Whigs already knew were coming.[8]

- April 15: Gage issues general orders: “The Grenadiers and Light Infantry in order to learn Grenadrs. Exercise and new evolutions are to be off all duties ‘till further orders.” Even British Lt. John Barker observes, “This I suppose is by way of a blind. I dare say they have something for them to do.”[9] At midnight that same day, the British Navy launches all of the recently repaired longboats and lashes them to the sterns of HMS Somerset, Boyne and Asia. It was quite conspicuous that all three warships now seemed ready for some amphibious assault. Paul Revere again consults with Dr. Joseph Warren on these strange developments. The two conclude that Revere should again ride out. This, too, was a false alarm.[10]

- April 18 Day and Evening: Per Mr. Waters (the same as above), Bostonians take notice to “an uncommon number of officers” seen “walking up and down the Long Wharf”. One townsman also reports they had seen a light infantryman in a retail shop with his accoutrements on, as if ready for a campaign. These concerns are immediately transmitted to Dr. Warren.[11]

- April 18 about 2 PM: Sailors come ashore, probably to be ready to man the longboats later.[12]

- April 18 before 7 PM: The British send out a party of mounted scouts via Boston Neck, “just before night”, which too must have been relayed to Dr. Warren.[13]

- April 18 by 8 PM: The Navy begins repositioning its longboats alongside HMS Boyne , which seems to have been moored near Long Wharf.[14]

- April 18 around 8 PM: With all that Warren learned, he this time summons William Dawes Jr. to ride out, but only to pass information to Adams and Hancock, not to raise an alarm. Warren feared issuing a third false alarm, so wanted more evidence before proceeding.[15]

- April 18 9 PM: Boston Neck gate and Charlestown Ferry are closed per the nightly curfew in place. (So Dawes left before then.)[16]

- April 18 10 PM: The British troops begin mustering on Boston Common, their embarkation point for the Charles River crossing, before their march to Concord.[17]

Given all that had happened on April 18, did Dr. Warren really need an informant at all? He apparently had none for the days prior, when he sent Revere on two false alarms. Why would he need one now?

Again, the only evidence of the informant is Mr. Waters’s dubious statement. But given all we know of Dr. Warren’s intelligence and facts before him, and of Warren’s desire to be in the thick of events (he volunteered in the battle the following day, and also volunteered to be in the redoubt at the Battle of Bunker Hill), I propose something different. Certainly, Warren must have wanted some sure verification this time, before sending Revere out on a third alarm ride. And there was time to verify, since Dawes was already on his way, though as a mere informational courier.

But did he need an informant to get the verification? I think not. Why not?

Note, again, that the British troops were mustering at 10 PM. Note too that Revere’s own depositions state that “About 10 o’Clock, Dr. Warren Sent in great haste for me, and beged that I would imediately Set off for Lexington, where Messrs. Hancock & Adams were, and acquaint them of the Movement…” I propose that “about 10 o’Clock” was soon after 10 o’clock, and that Revere was sent for in “great haste” implies Warren now had some definite verification to finally send Revere on his most famous of his three alarm rides.[18]

The idea most historians have proposed is that the impetus for this “great haste” was the secret informant, based on the dubious source material cited above. I think I have satisfactorily dismissed the notion of a secret informant, but sure, Warren could have also learned of the British muster by an ordinary “informant” (looser interpretation of the word), such as any of the various townspeople that were roving the streets as a city watch, or just some random eye witness. Indeed, it seems like many townspeople were about that night and had deduced the obvious. Recall the story of Lord Percy, who came upon a group of townsmen in earnest discussion. “The British troops have marched, but they will miss their aim,” they said. Percy replied, “What aim?” “Why, the cannon at Concord,” came the shocking retort.[19]

Instead of an informant, I propose the “great haste” was in response to Warren seeing for himself the troops mustering on Boston Common at 10 PM, and the boats arriving there for the embarkation. After all, Warren’s house was only about half a mile from the Green, or less than a ten-minute casual stroll, though the good doctor would have hurried faster than that. Also, Warren had to know quite quickly after it had begun of the embarkation in order to give Revere the message to light two lanterns in the Old North Church, “two if by sea”. And Warren wanted firm proof before sending an alarm rider once more, so would have likely desired firsthand proof. Finally, consider this: if you were in charge of Boston’s Revolution and got wind of (or had a hunch about) the British mustering a few blocks away, wouldn’t you go see for yourself? I sure would. Warren’s astuteness aside, we cannot underestimate human curiosity. The good doctor might have just gone wandering for the firm proof he needed when he stumbled upon the British embarkation.

Warren’s first biographer Alexander Everett supports this alternative narrative of what the doctor did on the evening of April 18, but unfortunately cites no sources in his 1836 biography. However, Everett’s work, based likely on interviews done in the years following the Revolution, has proven to be mostly reliable in other particulars of Warren’s life, and so perhaps can be trusted in this instance. Everett wrote, “At about nine o’clock [we know it was more like 10 PM], on the evening of the 18th, the British troops intended for the expedition were [starting to get] embarked… in boats at the bottom of the Common. Dr. Warren inspected the embarkation in person; and, having returned home immediately after, sent for Colonel Revere, who reached his house about ten o’clock.” Everett makes no mention of an informant.[20]

Everett’s story is the one that makes most sense with the circumstantial evidence I have presented here. Warren knew there was something going on with the troops that day in Boston, learned of the boats being at the ready alongside HMS Boyne, learned of at least one light infantryman suited up as if ready to go on a campaign, and knew of the mounted British scouts sent out the Boston Neck before nighttime. Given all of this, he felt justified in sending William Dawes to Lexington. But then, if he wanted a sure verification that the British were marching out, he had to wait for proof. Rather than a secret informant, for which almost no evidence supports, he could have walked the several blocks from his house to Boston Common to see for himself, just as Everett’s story suggests, just as Warrren’s character supports given his actions in the following weeks. Upon seeing the British troops embarking, he sent some aide for Revere and hurried back home to meet him. (Given the timeline, I suspect Warren’s aide actually went with him to the Common, before fetching Revere, so that the two could meet at Warren home’s shortly after 10 PM. This aide was likely Warren’s top apprentice and household resident Dr. William Eustis. All we know for sure by Revere’s own words is that he was summoned to meet Warren.)

While disproving historical inaccuracies when no firm evidence exists to the contrary can be almost impossible to do with perfect confidence, I believe the burden of proof now resides with those myth mongers who still hold strong to the secret informant theory. Simply put: there is not enough to argue that there was an informant at all. However, there is much circumstantial and even explicit secondhand reliable source material to suggest the contrary. That is, Warren needed no secret spy to deduce the obvious. Based on the many things happening in Boston, Warren had little doubt of an impending expedition, yet he waited for one more sign, and so sent only Dawes. When the British actually began to embark, Warren witnessed it himself, and with that he was certain, and so sent Revere. Warren’s only informant was his own two eyes.

[Featured Image at Top: The Midnight Ride of Paul Revere. Source: National Archives]

All dates are 1775 unless otherwise noted.

[1] David Hackett Fischer, Paul Revere’s Ride (New York: Oxford University Press, 1994) 96.

[2] See J. L. Bell’s blog series at Boston 1775 for Apr 24, 2008, at http://boston1775.blogspot.com/2008/04/who-tipped-off-samuel-adams.html and the four posts beginning with April 11, 2011, at http://boston1775.blogspot.com/2011/04/which-is-side-that-i-must-go-withal.html.

[3] Mr. Waters’s statement, in Jeremy Belknap’s Journal (Oct 25), in Proc. of MHS (Boston: Mass. Hist. Soc., 1860) 4:84-86 http://google.com/books?id=-glM5Q_s81kC.

[4] See the 2008 blog post by J. L. Bell, which notes of another female that came to Samuel Adams days before the British march, warning the British would come. However, I have found no evidence linking that supposed informant to Warren’s.

[5] The original Intelligence, Mar 9, [in French], in the Gage MSS, Clements Library, Univ. of Michigan, but without a translation. It appears transcribed but not translated in Allen French’s General Gage’s Informers (Ann Arbor: Univ. of Michigan Press, 1932) 11-13, with a synopsis following. Thank you to Ms. Vicky Lee Chan for her machine-assisted translation of the letter. Also see Journals of Each Prov. Congress of Mass. (Dutton and Wentworth, Printers to the state, 1838) 77, 84 http://books.google.com/books?id=iFVMkRsFQh4C. The entire story of the scouts comes from De Berniere’s Narrative in Coll. of MHS (1816) 2:4:214-15 http://books.google.com/books?id=wggQAQAAMAAJ.

[8] Lord Dartmouth to Gage, [Secret] Jan 27, 1775, in Carter, Clarence Edwin, ed. The Correspondence of General Thomas Gage with the Secretaries of State and with the War Office and the Treasury 1763-1775 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1931-33) 2:179-83.

[9] John Barker’s Diary (Apr 15), in The British in Boston – The Diary of Lt. John Barker, ed. Elizabeth Ellery Dana (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1924) 29 http://pds.lib.harvard.edu/pds/view/2581128; also Frederick Mackenzie’s Diary (Apr 16), in A British Fusilier in Revolutionary Boston, ed. Allen French (Cambridge, MA: Harvard Univ. Press, 1926) 50 http://www.archive.org/details/britishfusilieri009630mbp.

[10] Paul Revere to Jeremy Belknap, [circa 1798] (cited below). Graves to Philip Stephens, Apr 11, in Graves’s autobiography The Conduct of Vice Admiral Samuel Graves…, ed. George Gefferina (unpublished, begun circa Dec 11, 1776, completed Dec 1, 1777) original in British Library Ad. 14.038 and 14.039, a transcription in Mass. Hist. Soc., given under Apr 15. Also, Somerset’s journal, in ADM 51/906, UK National Archives (UKNA), Boyne’s journal, in ADM 51/129, UKNA, Asia’s journal, in ADM 51/67, UKNA.

[13] Mr. Waters’s statement, in Jeremy Belknap’s Journal (Oct 25), in Proc. of MHS (1860) 4:84-86; Fischer 93-94. The time is based on the fact that Cambridge Civil Twilight ended just before 7:00 PM, per the US Navy’s Sun & Moon Calculator at http://aa.usno.navy.mil/data/docs/RS_OneDay.php.

[14] Graves’s Conduct (Apr 18), this portion also in Naval Docs of the Amer. Rev. 1:192. Boyne’s exact position is unclear from her journals, in ADM 51/129, UKNA.

[15] There is no evidence that Dawes (or Revere) carried written intelligence, probably just oral (see notes below). Instead, I propose, as given in the text, Dawes was sent as a preemptory warning, and Revere was sent only after Warren had definite confirmation.

[16] William W. Wheildon, Curiosities of History: Boston… 1630-1880 (Boston: Lee and Shepard, 1880, 2nd ed.) 36 http://books.google.com/books?id=w4MUAAAAYAAJ.

[18] Paul Revere to Jeremy Belknap, [circa 1798]. The earlier two depositions by Revere, from 1775, also agree. The three depositions are as follows: “Deposition Draft”, circa May 1775; “Deposition Draft [Corrected Copy]”, circa May 1775; “Paul Revere to Jeremy Belknap [circa 1798]”. The originals of all are at MHS, but reprinted in many places, the latter is in Proc. of MHS (1878) 16:371-76 and at http://www.masshist.org/database/onview.cfm?queryID=112.

[19] Charles Stedman, The History of the Origin, Progress, and Termination of the American War 2v. (London: Printed for the Author, 1794) 1:119. This incident seems to imply there was no curfew in the town, even though it had been sealed off. However, equally plausible, there was indeed a curfew, and these were gathered members of one or more legally appointed town watch parties.

[20] Alexander H. Everett, Life of Joseph Warren, originally published separately in 1936, republished in American Biography 10:91ff., ed. Jared Sparks (New York: Harper and Bros., 1856) 120 http://books.google.com/books?id=DHUWAAAAYAAJ. Everett’s material is completely unsourced: he relied on a host of undocumented letters and on various interviews decades after the fact.

9 Comments

Perhaps the most interesting, and certainly frustrating, aspects of trying to write about intelligence activities is that they are, by nature and for very practical reasons, supposed to be secret. In my forthcoming book on American intelligence during the Revolutionary Period I found that presenting both sides on issues such as Mrs. Gage’s possible role, John Honeyman’s story and others was the best I could do. Washington was a strong believer in protection of “sources and methods” and the fact that this was a civil war meant that protection of individuals involved had a very practical purpose from the start.

Considering the administrative structure and physical environment surrounding Gage’s headquarters and troop locations I would, as a former intelligence officer, assume that several kinds of agents were reporting on activities, logistics, troop strength, etc. As to whether Dr. Warren had a particular “source” who could provide “plans and intentions” information, I’m afraid that knowledge died with him at Breed’s Hill.

In any event, luckily he did not like nor trust Dr. Benjamin Church, for had he shared his sources with him we probably would know much more about them from Gage’s papers.

It is always fair to present both sides, particularly given the apparent scope of your forthcoming book. I only beg that you help perpetuate the evidence I give above when describing the anti-Mrs. Gage side of the story. In particular, please help to disseminate the detail from Everett that says Warren observed the embarkation himself: this is something that has been long overlooked in this tale. Obviously, if true, then Warren needed no informant.

This issue would make a excellent topic for a panel discussion at some forum. Having some experience in counterintelligence I may see some aspects of the Mechanic’s collection capabilities in a different light than perhaps others. From all I have read and researched, I just do not know with any certainty who his sources were inside of the British professional and social establishment. I do know the Mechanics had observational reporting assets in Boston as well as people in contact with British officials and officers.

I enjoyed your fine article and also had read Mr. Bell’s earlier articles on the subject.

It is definitely true that there is much mystery on the particulars of the Mechanics. Too bad you cannot debrief Revere himself on the subject! And too bad he was not the type to keep a diary.

With your work on Revolutionary intelligence, if you haven’t already, be sure to check out all of it in the Gage MSS. It’s pretty exciting (to the sorts of people that read and write for this online journal at least) to hold in your very hands the intelligence that led Gage to order Lt Col Smith west towards Concord, thus causing the story above of Revere and Warren. And for you especially: to hold the actual treasonous letters of Benjamin Church!

Regarding a forum on this topic: if ever this is one, I hope I can attend. And thank you sir, for your kind compliments.

Wouldn’t the very fact that Paul Revere needed to be told whether the British were going by land or by sea point to their not being a high level source? Presumably a top level source would know beforehand which route the army was going to take, however if the information was gleaned from low level informants or via observation from concerned citizens, that sort of information wouldn’t be known until the moment of departure.

Indeed, had there been a top level informant, the Americans then should have had better intel. Given Revere’s unknown verbal words to Hancock and Adams at least implied that they were in danger, causing them to escape, it seems the American intel was not that great. So, it must have been gleaned from other than a high level source, for if there was a high level source, the Americans should have known Hancock and Adams were not the targets.

Excellent analysis, Derek. I’ve never believed the mystery informant story. The signs were all around, right in front of Warren’s face. No need for a secret source. And I also have never bought the Mrs. Gage story. In fact, I believe that the couple had another child after Gage returned to England. Doesn’t sound like an estrangement to me. Hopefully, you and John have put this myth to rest.

Thank you, kind sir!

A lucid analysis. I particularly like your reference to “encampment gossip”. Even today, “water cooler talk” or “scuttlebutt” is common in workplaces and among service members. It might be entirely true, partially true, or completely inaccurate. Soldiers in 1775 would have been just as susceptible to conveying inference or sincere belief as fact when their statements were actually based on speculation.