There were many sieges during the American Revolution. Some are well-known even to novice students of the war, like Boston and Yorktown; others are known only to those who study in more depth, like Newport and Charleston. They lasted for weeks or sometimes months; the siege of Boston spanned almost a year. They pale in comparison to the longest siege during the conflict, a dramatic standoff that lasted almost four years. It occurred not in America but Gibraltar, the British bulwark at the entrance to the Mediterranean Sea, where British and German troops were hemmed in by a massive Spanish and French force. It is among the longest sieges in the last 500 years and the longest ever endured by the British army.

Gibraltar is a tiny bit of land, less than 3 square miles, but it sits in a highly strategic location guarding the entrance to the Mediterranean Sea from the Atlantic Ocean. The peninsula jutting from the Spanish coast features a mountainous rock outcrop, topology that makes it highly defensible. It was granted to Great Britain in 1713.

Fifteen months after France declared war on Great Britain in 1778, in direct support of the American Revolution, Spain likewise declared war. In short order, the two nations formulated a plan to divest Great Britain of its strategic enclave that bordered Spain. But it was no easy proposition; the British had turned Gibraltar into a major military installation with a fortified town, a harbor for warships, strong landward defenses and, perhaps most important, a network of caves carved into the steep stone cliffs that was impervious to any type of bombardment or direct assault. Having anticipated trouble when France initially declared war, General George Augustus Elliott had already begun preparations for war including extensive improvements to fortifications, laying in of supplies, and procurement of reinforcements of both ships and soldiers.

The Spanish, assisted by the French, expected to capture Gibraltar quickly but nonetheless refrained from a foolhardy frontal assault. Instead, they laid siege. On the land side, batteries were built for bombardment, and trenches dug to gradually approach the peninsula’s defenses. At sea, a naval blockade was established. It was a simple matter of hemming in the defenders and then starving them out. The operation commenced in the summer of 1779, and by winter the effects of deprivation were being felt by the Gibraltar garrison. Food grew scarce, and then more scarce, and finally so scarce that rations for soldiers and civilians alike were barely enough to sustain life. The small spit of rocky land had very little natural wood, so fuel too was agonizingly hard to come by during the winter. Scurvy broke out. But the garrison of British, German and Corsican soldiers continued to do their duty. Finally in the spring of 1780 a British fleet broke through the blockade and brought provisions as well as additional troops.

Summer saw intensified bombardment by the Spanish, returned with vigor by the British, but no change in the overall standoff. The siege continued. As winter approached, provisions once again grew short. The cold months ending 1780 and beginning 1781 were almost as difficult as the previous year, but once again the defending garrison endured. And once again, in the spring, a British relief fleet broke through the blockade and brought new life to the garrison. Out of frustration, the Spanish unleashed a terrible bombardment to try to destroy the supplies as they were being unloaded, but instead only devastated the town without achieving any military benefit. Anticipating the challenges ahead, the British evacuated most of the civilian population when the relief fleet left port and again pierced the blockade.

The French and Spanish resolved to reduce Gibraltar by military force and spent the summer of 1781 building up greater forces. They were prepared for a great attack in November, a month after the British surrender at Yorktown in America. The British, having gained information of the impending assault, took a great gamble – they committed half of the garrison to a nighttime preemptive strike, sallying out of their defenses into the Spanish trenches in the darkness, destroying guns and stores, burning batteries, smashing equipment and fortifications, killing and striking terror into the unsuspecting Spanish soldiers. By the time the Spanish rallied for a counterattack, the British invaders had returned to the safety of their own lines. The victory was so significant that it is remembered still as “The Sortie.”

The assailants, although bruised, were not about to give up. They devised a new plan, and with it a secret weapon. Destroying the seaward fortifications was impossible because much larger guns with longer range could be mounted on land than on ships; any approaching ship would be devastated before it could bring guns to bear and batter the fortifications. But a French military engineer, Colonel Jean Claude Eléonore Le Michaud D’Arçon devised a plan – floating gun batteries, protected by eight-foot thick wooden sides that would deflect or absorb iron cannon balls. That in itself was no innovation; floating batteries had long been used in warfare, but they were vulnerable to “hot shot”, cannonballs heated red-hot that nested in the wooden armor and set the batteries on fire. D’Arçon’s vision was to circulate water through the protective sides using metal tubing, like blood flowing through the veins of an animal, to cool off any encroaching hot shot and render the batteries invulnerable.

It was a bold and clever scheme. The French and Spanish high command heartily supported it, imagining these gun-laden barges clad in their self-cooling wooden armor imperviously battering the coastal defenses into gravel and allowing the army to storm Gibraltar, bringing the fortress into Spanish hands at last! But achieving this dream was not so easy. Not intended as seagoing vessels, the floating batteries had to be built nearby. Converting existing, expendable hulks into formidable war machines took time. And every day the siege dragged on, month after month and then year after year, armies of soldiers and laborers had to be fed, clothed, sheltered, kept in good order.

Work on the new weapons progressed problematically. Design revisions were made. The tubing that circulated water like blood through the veins of an animal was very difficult to construct, and it leaked, and it required modifications, and experiments revealed flaws that required more changes. Workmanship of the hulls was poor, with badly-installed caulking and faulty bilge pumps. The siege continued, day upon day at enormous expense. Once the amazing floating batteries were ready, the assault could begin. When would they be ready? Why weren’t they ready now? Couldn’t they be speeded along, so the deadlock could be broken and Gibraltar could be Spanish and the commanders be heroes and the troops could go home?

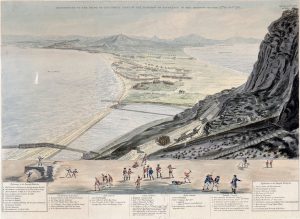

By September 1782 everything was ready. Well, not everything was ready, but patience had worn out and action was needed. The grand assault was planned with such deliberation and ceremony that thousands of Spanish spectators flocked to nearby hills to witness the impending demise of fortress Gibraltar. Over 13,000 troops were ready on the landward side, waiting to pounce when defending guns were overset by the seaward assault. Twenty great warships and dozens of smaller craft moved in from the sea to destroy the fortifications. Leading the flotilla were the floating batteries, ten strange barge-like craft with sloping wooden sides, bristling with heavy cannon. Hundreds of guns thundered from land and sea, pelting Gibraltar with a rain of iron. The heavily-outnumbered defenders responded in kind, lashing back at their assailants.

The floating batteries drew in with impunity. Defenders used the conventional technique of pounding the batteries with hot shot, not knowing about their specially designed cooling systems that would circulate cooling, protecting water like blood through the veins of an animal. Red hot iron cannonballs imbedded themselves into the thick wooden armor, and gradually set it smoldering, for there was no water to douse them; the technical challenges had proven too great, and the cooling systems were not working, not working at all. The wooden armor was just wood, vulnerable to intense heat. The batteries began to burn.

As thousands of Spanish spectators, legions of troops and a fleet of sailors looked on in horror, one of the wondrous floating batteries, upon which they’d pinned their hopes of victory, exploded, shaking the ground, the sea, and the spirits of the assailants, raining shattered bits of wood, crewmen and artificial animal veins over the entire unfolding battle. Then another one exploded. Then a third. Now knowing the destiny of their stricken vessels, the crews of the seven remaining batteries abandoned and scuttled them. The ships withdrew, the soldiers stood down, the assault was over. Gibraltar still stood firmly in British hands.

Within weeks of the failed final assault, another British relief fleet arrived. With war winding down in other parts of the world, the fleet was able to deliver more troops and supplies than before, leaving the garrison stronger than ever. Although the siege continued, it did so without spirit. In February 1783, with peace negotiations in progress, hostilities ended; the weary assailants went home while the defenders celebrated their tenacious survival of three years and seven months under siege.

The defense of Gibraltar is remembered as one Britain’s greatest military achievements, at least of the era. The regiments that participated received battle honors, something not given for any action in America. Mozart composed a piece of music commemorating it. Artists John Singleton Copley and Jonathan Trumbull (both American-born) rendered great paintings of the Sortie and the destruction of the floating batteries. But the most important commemoration of the victory is the very fact that Gibraltar remains a British territory to this day.

There are several excellent books about the Great Siege, including published memoirs of participants and modern studies. My own favorite is Gibraltar Besieged 1779-1783 by Jack Russell (London: William Heinemann Ltd, 1965); it relies heavily on first-hand accounts woven together with highly readable narrative to tell the story in a personable way.

[Featured image at top: Panorama of the Grand Assault by French and Spanish warships, showing ship exploding, infantry and artillery on land in right foreground. Source: Brown University Library]

3 Comments

Great article which serves to remind us that the American Revolution was the real Second World War, at least in western civilization terms. Speaking of blood coursing through animals’ veins, did you come across any references to the Gibraltar monkeys?.

As Mr. Mark said above – great article, Don, as always. Maybe letting newer readers know that the small British patrols out to the Boston colonial countryside to gather powder and arms escalated into a huge world war.

Great article, Don!