This article was originally published in Journal of the American Revolution, Vol. 1 (Ertel Publishing, 2013).

By Ray Raphael and Benjamin H. Irvin

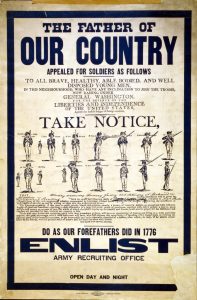

If you have ever studied the American Revolution, chances are you’ve seen the ubiquitous “Take Notice” recruiting poster, beckoning “all brave, healthy, able bodied, and well disposed young men” to “join the troops, now raising under General Washington, for the defence of the Liberties and Independence of the United States.” Reprints of this slightly battered broadside, which may be readily identified by the text scratched out just below the soldiers’ feet, have seen the light of day countless times. “Take Notice” appears in textbooks desperate for visual images to represent the Continental Army and the lives of its soldiers. It appears on the websites of patriot organizations and reenactment clubs, which, under banners like “God save the United States,” try to attract their own recruits. During World War I, army recruiters reframed the famous “Take Notice” broadside

to beckon brave, healthy, and able-bodied men to follow their forefathers and join in a new war effort, this time against the Central Powers.

The poster has circulated for a long time, but not so long as people have imagined. It dates not from the Revolutionary War, as textbooks and websites tell us, but from the military mobilization for the “Quasi-War” with France in 1798. A much less stirring event than the American Revolution, the Quasi-War never escalated into a full-blown military conflict.

How do we know that “Take Notice” hails from that later period, and not, as has so often been claimed, from the American Revolution? And what of its invocation of George Washington? Is the general’s name not conclusive proof that this recruiting poster was originally printed for the army of ’76?

The first clue may be found in the small print just above “Take Notice”: “Against the hostile designs of foreign enemies.” “Take Notice” was not likely to have been printed in 1776, for at that time, the people of the United States seldom characterized their enemies as foreign. They considered the British as their “Brethren” and “common kindred,” as they proclaimed in the Declaration of Independence that year. They looked upon belligerent Indians as “savages” rather than foreign powers. And though they certainly regarded the Hessian soldiers contracted by King George III as “foreign,” they characterized those auxiliary troops as mercenaries, or hired guns, motivated by money, not by “hostile designs.”

A second clue may be gleaned from who was doing the recruiting, or more precisely, who was not doing the recruiting. This poster could not have been printed in 1776 because it does not mention any particular state. During the Revolutionary War, the thirteen individual states recruited soldiers for the Continental Army. Only under very special circumstances, such as the formation of the 2nd Canadian Regiment, did the Continental Army recruit independently from the state and offer its own bounties, as appears to be the case in this “Take Notice” print.

Now comes the hard evidence. Notice the three officers referenced in the broadside, aside from General Washington: “Lieutenant Reading,” “Major Shutes,” and “Lieutenant Colonel Aaron Ogden.” According to official records, all three served in expectation of a war with France in the late 1790s. On a list labeled “Officers Appointed under the Act of July 16, 1798, ‘To Augment the Army of the United States, and for Other Purposes,’” prepared by the Secretary of War and communicated to the Senate on April 17, 1800, are the names “Lieutenant Colonel Aaron Ogden,” “Major William Shute,” and “First Lieutenant Thomas Reading, Jr.” Further, on that list, the three officers appear under the heading “Eleventh Regiment of Infantry,” in perfect conformity with the “Take Notice” poster.[1]

War Department Papers confirm that “Lt. Col. Aaron Ogden, Commandant of the Eleventh Regiment of Infantry” was still serving in that capacity when Major General Alexander Hamilton recommended him “for the post of Deputy Quartermaster General” on March 20, 1800.”[2] These papers further reveal that Major William Shute of the Eleventh Regiment was involved in various disputes arising from the expenditure of funds between 1798 and 1800.[3] The papers do not disclose much about First Lieutenant Thomas Reading, Jr., but that is consistent with the 1798 officers’ list, in which the word “resigned” appears after his name. The evidence is convincing: men named Ogden, Shute, and Reading held commissions in the Eleventh Regiment of what was called the “Additional Army,” raised by Congress in 1798 to prepare for a likely war with France, and they held the exact same ranks as mentioned in the “Take Notice” recruiting poster. It’s a perfect match.

But do the officers mentioned in the poster also match official records from 1776?

Aaron Ogden, future governor of New Jersey (1812-13), served in the First New Jersey Regiment during the Revolutionary War (not the Eleventh Regiment, as listed in the “Take Notice” print). Ogden held offices as a paymaster in the First Establishment (1775) and Second Establishment (1777) of the Continental Army. Later, he became a captain-lieutenant and captain. According to George Washington’s General Orders of May 5, 1778, Ogden held the rank of “brigade major in Gen. Maxwell’s brigade” at Valley Forge, his highest office during that war. He had not yet been commissioned lieutenant colonel, the post he held at the time of the “Take Notice” poster.[4]

William Shute also held various offices in the New Jersey line of the Continental Army during the Revolution, but not that of major in 1776. (He did rise to the rank of colonel, but only in the militia.)[5] A man named Thomas Reading served as well, but he never rose higher than a captaincy, and he was never referred to as Thomas Reading, Jr. Captain Reading of the Revolutionary War was born in 1734; quite possibly, “First Lieutenant Thomas Reading, Jr.,” from the 1798 list of officers, was his son.[6] In sum, nothing in the historical record indicates that these three men served together in 1776, in some undefined Eleventh Regiment with no state affiliation, with the exact same ranks as listed on the “Take Notice” poster.

Finally, there is a piece of rock-solid evidence revealed only upon careful examination of the print. Just to the right of the soldier depicted in Figure VIII (the first large-sized soldier from the left in the second row) appears the name of the engraver: B. Jones. A quick search of American Engravers upon Copper and Steel: Biographical Sketches, Illustrated, a reference manual for the engraver’s trade, reveals an artisan named Benjamin Jones who worked in Philadelphia between 1798 and 1815.[7] A search for Benjamin Jones in Evans Early American Imprints, the classic collection of documents from the Founding Era administered by the American Antiquarian Society and accessed through most major research libraries, reveals that Jones engraved a 1798 edition of Regulations for the Order and Discipline of Troops in the United States (Philadelphia, 1798). First drafted after the Valley Forge encampment of 1777-78 by Frederick William Augustus von Steuben, Inspector General of the Continental Army, these Regulations appeared frequently in print during and after the Revolutionary War, but not until 1798 did Benjamin Jones provide engravings for that important book. Lo and behold, the second page of Jones’s 1798 edition features an engraving of soldiers, arrayed in two rows, performing military exercises, and again, the match is perfect: Jones’s engraving of soldiers, which first illustrated the 1798 edition of von Steuben’s Regulations, is the same engraving that adorned the “Take Notice” print.

The evidence is clear and undisputable: this poster dates from 1798, not 1776. Why, then, has it become an icon of the Revolutionary War?

Answer 1

Respected research institutions appear to have certified it as such. To this day, in Evans Early American Imprints, the bibliographic entry for the “Take Notice” print, item #15103, reads: “United States. Continental Army. To all brave, healthy, able bodied, and well disposed young men …. [Philadelphia?: s. n., 1776].”[8] Routinely, other repositories pass on this listing, although the call number—“Ab [1798]-24” in the case of the Library Company of Philadelphia and the Historical Society of Pennsylvania, which hold an original—might suggest otherwise.[9] Even most scholars, if they inquire about the date, are likely to defer to the Evans bibliography, a widely accepted standard, rather than a particular institution’s call number, which can be based on any manner of factors.[10]

Answer 2

Not many Americans are aware that General Washington commanded an army in 1798, the year before he died. The military mobilization for the Quasi-War is little known and never celebrated. In July of 1798, amidst fears of a French attack on American soil, Congress passed a bill authorizing President John Adams to raise an “Additional Army” headed by none other than George Washington, who accepted the appointment under the condition that he would “not be called into the field until the Army is in a situation to require my presence.”[11] Recruitment proceeded apace, but since the only fighting took place on the high seas, Washington was never called to serve. Though important in its own era, the Quasi War with France, and the political and diplomatic rancor that attended it, have been upstaged in our national narrative by the Revolution. The War of Independence far outshines a war that Congress never formally declared. The year 1776 is sacred ground. Any time we can attach significance to it, we will. Such is the way of iconic moments.

Answer 3

Graphic deprivation. We have very few images contemporary to the American Revolution, yet we possess a strong desire for visual representations of that momentous event. Advances in photographic reproduction in print media in the latter decades of the twentieth century heightened the demand for historical graphics, and electronic media now practically require more than mere words. “Take Notice,” which depicts eighteen figures in various stages of military drill, is too satisfying to question. Much as romantic paintings of a folk legend, Molly Pitcher, liven textbooks by presenting allegedly historical images of a Revolutionary woman, so does this sequence of drawings bring us face-to-face with Revolutionary soldiers—or so we would like to believe.

Answer 4

“Take Notice” looks so authentic. This is no accident. The military mobilization of 1798 specifically and self-consciously emulated the martial culture of the Revolutionary War. That was the young nation’s only heritage, and it was precisely why Congress pressed an aging George Washington into service one last time.

Answer 5

If you have it, flaunt it. At first glance, “Take Notice” works too well not to reprint in textbooks and on the web. Like rumors, mythologies can stand on their own if they are good enough, as this one is. Their beauteous glare masks minor imperfections, such as contradictory evidence. Enraptured, we don’t suspect that anything could be amiss. Even scholars, in the face of a plausible and welcomed story, can be taken in, seeing no need for further investigation. But if a myth fosters a greater good—in this case, reverence for the military efforts of the Founding Era that allowed our nation to achieve independence and then protect it—why does any of this matter? What do we gain by setting the record straight? Do we now have to remove this evocative image from historical presentations of the Revolutionary War? Such questions are not easily answered. Some mythologies, like Paul Revere waking up the sleepyeyed farmers, do genuine harm: if those country farmers were really so asleep, how could they have staged a full revolution and cast off British rule the previous year? The “Take Notice” myth, on the other hand, simply fails to acknowledge the Quasi-War, an event with no great bearing on the nation’s overarching history or heritage. Some might argue that not much is lost on that account.

But by allowing “Take Notice” to stand as a true representation of the Revolutionary War, we lose on other fronts.

First, we set a dangerous historical precedent: don’t bother with historical accuracy, if what you see looks convincing enough. This bad advice leads down a slope that is indeed slippery, undermining the very discipline of history.

Second, we succumb to the tyranny of iconic moments. The “Take Notice” story serves as a warning: no single event can ever stand for the whole of history, not even the monumental events of 1776. Time marches on and history is made over the long haul.

Finally, false evidence can lead to false conclusions. If “Take Notice” were in fact the sole extant recruiting poster of the Revolutionary War, we would be obliged to study it as carefully as possible to see what we might learn. In that event, we might conclude that young Americans in 1776 enlisted in General Washington’s army to “view different parts of this beautiful continent.” But did the “continent” actually bear such appeal in 1776? Did prospective soldiers from Virginia really want to travel to Massachusetts? Did recruits from New Hampshire care one farthing about North Carolina? Perhaps so, perhaps not. In 1776, the Declaration of Independence created the United States, but those states existed only in a loose and informal confederation with one another. By 1798, however, the people of the United States had ratified the Constitution and established a nation. In the process, they had cultivated a sense of national citizenship and stoked a national consciousness. At that moment in time, a young recruit’s ambition to travel the continent seems more probable. When properly dated, “Take Notice” lends supports to the idea that people had begun to think more nationally. Only by paying close attention to time—distinguishing 1798 from 1776—can we use shreds of evidence such as a recruiting poster to better understand our nation’s history.

[Featured Image: The Original Engraving — Benjamin Jones’s engraving of a solider performing the manual exercise, as it appeared in a 1798 edition of Baron von Steuben’s Regulations for the Order and Discipline of the Troops of the United States. Source: American Antiquarian Society]

[1]American State Papers: Documents, Legislative and Executive, of the Congress of the United States (Washington: Gales and Seaton, 1832), Class V, Military Affairs, 1:149.

[2] Alexander Hamilton to Secretary of War James McHenry, March 20, 1800, Papers of the War Department, 1784-1800: http://wardepartmentpapers.org/document.php?id=38016

[3] http://wardepartmentpapers.org/index.php

[4] Legislative history of the General staff of the Army of the United States: (its organization, duties, pay, and allowances), from 1775 to 1901. (Government Printing Office, 1901), 60, 66. William S. Styker, Officers and Men of New Jersey in the Revolutionary War (Trenton: Wm. T. Nicholson, 1872), 69.

[5] Ibid., 31, 32, 53, 72, 346, 355.

[6] Ibid., 21; William Nelson, “New Jersey Biographical and Genealogical Notes,” Collections of the New Jersey Historical Society, 9 (1916):181.

[7] David McNeely Stauffer, American Engravings upon Copper: Biographical Sketches, Illustrated (reprint: New York, 1907), 147.

[8] To locate Evans 15103, go to the American Antiquarian Society online catalogue, click “keyword,” and type within quotation marks the first few words of the poster: “To all brave, healthy, able bodies…”

[9] For the LCP and HSP catalogue listing, on the LCP website, go to WolfPAC, through the Catalogs page, and type in the first few words of the poster, as in footnote 8. The Library of Congress has recently corrected its catalogue listing: http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2001700432/ But the LOC still files the World War I recruiting poster, which includes “Take Notice,” under “Military Personnel—American—1770-1790,” and it refers to the figure “loading, firing, and carrying a rifle” as a “Revolutionary War era soldier”: http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/00651804/ The mistaken date for the “Take Notice” poster was observed at least as early as

1905 by Charles Bolton of the Library of the Boston Athenaeum: The Nation 80:2073 (March 23, 1905), 228.

[10] In conjunction with administering the Evans series, the AAS also administers the North American Imprints Project, tied in with the British Library’s English Short Title Catalogue. These institutions serve as central clearinghouses for cataloguers, much as the Library of Congress does for books. The catalogue entry quoted above is in a sense an “official” one, traveling with reproductions of the poster wherever they go.

[11] Papers of Alexander Hamilton, Harold C. Syrett, ed., (New York: Columbia University Press, 1961), 22:4-5 and 17-19.

Authors:

Co-authored by Ray Raphael and Benjamin H. Irvin. Ray Raphael’s bio is below.

Benjamin H. Irvin is a social and cultural historian of early America and the United States, working primarily in the Revolutionary period. His book, Clothed in Robes of Sovereignty: The Continental Congress and the People Out of Doors, published by Oxford University Press in April 2011, examines the material culture and ceremonies of state—including, for example, fast days, funeral processions, diplomatic protocols, and presentment swords—by which Congress promoted republicanism and revolution. Central to his study are the many ways that the American people challenged Congress and its vision of the United States.

9 Comments

Great article and nice job with the investigation. It seems that it is real easy for some to jump to conclusions about an item or a piece of history and then the myth is taken as true fact. I am glad that the Journal is taking the time to bring myths to the forefront and the investigative work to bring out the true facts. Thank you!

This poster hangs on the wall right near my desk. So imagine my surprise.

It’s one of those yellowed, rolled-up, parchment reproductions that my family got I don’t know when. But I just pulled out the tube it was mailed in, and it’s from Domino Sugar and says, “4 Famous American Documents.” The others are the Declaration, Bill of Rights, and the first Poor Richard’s Almanac.

Just looked around, and it seems it’s from 1966.

http://www.ebay.com/itm/1966-4-FAMOUS-American-Documents-from-DOMINO-Sugar-In-Original-Tube-/141195037692

At the bottom of the poster it simply says, “Call to Arms under George Washington,” which is accurate enough, I suppose.

But this is what I love about history, how it’s a constantly unfolding mystery, and like an archeologist, historians have to carefully brush the accumulated dirt off artifacts to see them clearly. Many thanks.

A fine and very convincing analysis, but one that overlooks important clue that this broadside certainly did not date from 1776, and was quite likely of post-Revolutionary vintage–the cut of uniform worn by the drilling infantryman, which looks very late-century to my eye.

Thanks for this, Donald. I know little about uniforms, so this is very helpful. If I have uniform questions in the future, how can I get in touch with you?

I first saw this in 1967 on a waste paper basket my mom got for my room. I even did a school report on it and got an A. And now thanks to this great article I now know almost everything I said was wrong. What is the statute of Limitation on a 2nd grade report?

Where is the original of this recruiting poster? I have a copy dated 1860 that says it’s an extraordinary revolution recruiting poster from the only original known to exist in the Historical Society of Pennsylvania. I looked at their web site but could not find any reference to the poster.

Hi Don, I feel that this 1798 Broadside is so rare that we really can’t find much information about it. If one may think that they may have an original one I guess the best way to date it is through a specialist in dating documents which may cost $2500! I’m still trying to figure out mine which seems most likely a lithograph. It’s on laid paper. I can’t even find out anything about your 1860 piece although I just now learned about this. I’m a great researcher but these Broadsides that we have are very difficult to find. I’m wondering if we can exchange pictures, measurements, etc. just to try and figure this out ourselves I guess? Any watermarks too? You said that yours is dated but mine isn’t. I’d really like to see where the date is printed on this and then compare the differences in margins on the piece, maybe mine was cut down?

Nevermind, found it after another day to find time to research your piece.

Hi Ray, great article! I’m hoping that you can give me further information about this Washington Broadside. Would it make sense that this would have been made by the earliest form of a lithograph. With the wording underneath the soldiers this could not have been done by typeset which was of the era. With all of the scribbling for the days of the week and irregular letters this definitely isn’t possible for typeset and not even possible for a plate print. This could only have been done by writing on a stone which would lead to lithograph. Lithograph started around that era 1796-1798. Could this possibly be a very early rare lithograph as well as a very rare Washington Broadside? If there are any others here reading this can you please give me your opinion if I’m correct about this. If I’m wrong I would still appreciate your opinion about this rare Broadside. I feel that this Broadside could have only been made by lithograph.