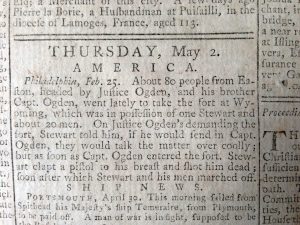

“Living on the frontier is easy!” said no one, ever. Case in point, on July 3, 1778, over 100 loyalist rangers under the command of Lieutenant Colonel John Butler along with a few hundred Seneca warriors descended upon Wyoming Valley, Pennsylvania and slaughtered over 300 soldiers at Forty Fort (named after the first 40 settlers to the region who built it)—most of them Connecticut and Pennsylvania militia.

Many may recognize this event as the Wyoming Massacre. It’s a brutal account of one of the more tragic events of the American Revolution. A few hundred militia under orders from Connecticut-born Lieutenant Colonel Zebulon Butler (no relation to John Butler), thinking they had the upper hand, were outmaneuvered by the numerically superior force and annihilated. This event eventually forced Congress to make a move against the Iroquois, launching what would become known as the Clinton-Sullivan Expedition.

But make no mistake; while this comes across as a typical (some might use the term ‘justified’) Native American revenge raid against white settlers, it goes much deeper than that. For instance, the keen eye might wonder why a Connecticut officer was placed in charge of a Pennsylvania frontier fort full of militia from Connecticut and Pennsylvania.

Would you believe that this massacre, and all the oddities with this story, had been precipitated by a series of wars between Connecticut and Pennsylvania? No, you’re not reading that wrong. At one point in time in American history, settlements from Connecticut and Pennsylvania were at war with each other. Let’s take a step back and establish the background that led up to this tragedy; this particular occurrence is rooted in events that took place over the previous decade and would culminate in bloodshed, treachery, and treason (who said history wasn’t fun?).

In the 1600’s, King Charles II accidentally (sure, it was an ‘accident’) gave the same tract of land in what is now North-Central Pennsylvania to both Pennsylvania and Connecticut, because apparently Royalty doesn’t need to care about such trivial matters, such as maps. As a consequence, the Pennsylvania government sold the same tract of land to various settlers as did Connecticut—and so both groups of settlers (from both colonies) had legal rights to the lands. Because that won’t cause any conflicts.

When Connecticut sent forth their newly established Susquehanna Company to survey the tract of land for the creation a new settlement in 1753, they discovered that Pennsylvania settlers (who would become known as Pennamites) had already established small communities along the Susquehanna River and throughout the Valley. Despite the fact that their land grant had come a full 19 years after the grant given to Connecticut in 1662, the Pennsylvania families had arrived and settled first. A situation to which we can imagine that the Pennamites promptly mocked the men of the Susquehanna Company.

There was also the matter of dealing with those pesky Indians who had, against the wishes of the Connecticut provincial government, settled on that land decades earlier (the nerve, am I right?). Among the native locals was Chief Teedyuscung, a prominent (and beloved) Indian who had taken part in the Treaty of Easton, between the Iroquois and the provincial governments of Pennsylvania and New Jersey, and who had settled in Wyoming Valley during the mid-1750’s.

Connecticut settlers (known as Yankees) started to arrive in Wyoming Valley and established towns (like Wilkes-Barre) and forts (like Fort Durkee and Forty Fort) along the north and west face of the Susquehanna River. Pennsylvania settlers responded in kind, building Fort Wyoming and Fort Ogden in an attempt to slow or stop completely the Yankee encroachment into the region.

There were plenty of situations where people were intimidated, or groups of local militia showed up in force to stay hostilities, and of course plenty of people were threatened—all since the first interaction between the two groups. But despite growing disputes between rival Pennamite and Yankee families over who owned what tract of land, there was very little bloodshed at first. But that all changed in 1763 when Teedyuscung was murdered—burned to death in his home by an unknown arsonist while he slept.

Consequently, Teedyuscung’s son, Chief Captain Bull, launched an incursion with a few hundred Delaware against the Connecticut settlers, whom they blamed for the murder. His raiding party burned down houses and killed over two-dozen people. The Yankees saw the Pennamites as instigators and from that point forward, it was on like Donkey Kong.

The Hatfields and McCoys don’t have anything on this. During the next few years, some people were killed, houses and property destroyed or looted, but most people were just evicted off their property—land which fell legally under both Connecticut and Pennsylvania charters. The Valley became something of a no-man’s land.

In 1771, to help with the defense of the land, the Yankee settlers—mainly at the behest of Zebulon Butler—also brought in the aid of the Paxton Boys, a group of Scotch-Irish frontiersmen from Lancaster County. These militiamen despised Pennsylvania as much as the Yankees. Captain Lazarus Stewart, the leader of the Paxton Boys, along with the rest of his company of men, were promised land in Hanover Township on the Yankee side of the river if they helped secure the forts and territory from the Pennamites. Little did they know that these actions would lead to a cacophony of errors and, eventually, to their deaths.

As it happened, the Pennamites had their own trouble with the government of Pennsylvania. Despite countless pleas to resolve the land dispute, and despite legislature which continued to uphold the land grants for the Pennamites, there had not been any authoritative, unified government in place (there was no federal government at this point) and so none of these laws were enforceable on the Yankee side of the river. Sure, instigators who crossed the river and Yankee militia leaders were subsequently arrested and detained at the Easton, Pennsylvania jail when they crossed into Pennamite territory, but that did not bring back the homes and farms of the Pennamites.

Four months after the Battles at Lexington and Concord, in August of 1775, a group of 700 Pennsylvania militiamen traveled to Wyoming Valley and successfully pushed back the Yankees from the west bank of the Susquehanna before having to withdraw a short time later when they were ambushed on their way to Wilkes-Barre. Pennsylvania had been unable to hold onto the land it claimed was theirs and in the eyes of the Pennamites, that was as damaging to them as any Yankee militiaman.

Pushing forward a bit to 1778, we come across Zebulon Butler and Lazarus Stewart again, but this time they were elected to maintain the Continental garrison at Forty Fort. The American Revolution, in the midst of its third year, had caused many settlers both unease and hardships. None of the tension from the previous conflicts had gone away and, besides fighting each other, the Pennamites and Yankees had to worry about a possible British invasion.

John Butler, recruiting for a new Loyalist Ranger unit, drew upon these tensions. Disaffected Pennamites who had been forced to live on the far outskirts of the Valley, who had seen their lands set on fire and their property destroyed by the Yankees, were prime targets for his recruitment efforts. Why not join with the British and earn a chance to get back at those pesky Yankees? After all, the Pennsylvania government can’t seem to get anything done for you. Seemed legit, they thought. And why wouldn’t it? The Pennsylvania government had not succeeded—the British were as good an option as any other.

Butler also had no trouble recruiting the help of the Seneca Indians and whatever remained of the Delaware Indians who had also been driven from their lands in Wyoming by the Yankees—many also still felt the pain from the loss of Chief Teedyuscung. The combined force of the social history of the region mixed with strong feelings of revenge made for a ticking bomb (or a powder keg with a lit fuse, if you will). All Butler had to do was direct the explosion. In the summer of that year he made his move—the attack at Forty Fort was the unleashing of decades-old hatred and built-up resentment. Among the dead following the massacre were Lazarus Stewart and some of his kin, along with many of his Paxton Boys.

The Pennamite win would be as short-lived as any other they had had previously. When news spread of the Tory and Indian involvement in the massacre, Americans were outraged. The country—now under control of a Congressional authority—demanded action and that action would be the taken under the command of General John Sullivan. In 1779, Sullivan led a small army of Continental troops and Pennsylvania militia in an aggressive campaign which started at Easton, Pennsylvania and ended in New York; along the way he and his army left dozens of Indian villages torched and their land and crops destroyed. Because when your enemy feels threatened and motivated by the necessity of revenge for survival, launching a scorched-earth campaign and destroying their homes is definitely the way to go (this author says sarcastically).

Brutality begat brutality. But it seems that without the initial disputes between the colonies of Pennsylvania and Connecticut preceding the war, the massacre at Wyoming may never have materialized. Incidentally, the hostilities did not stop. Indian raiding parties would continue to harass the Wyoming Valley for years to come, especially in response to Sullivan’s campaign, and the Pennamite-Yankee war continued on until 1799 (20 years after Sullivan’s Expedition, because why quit when you’re ahead?) when, under authority from the newly established federal government, the Yankee lands were folded into Pennsylvania and all the Yankees were made Pennsylvania citizens with full rights to their lands. For more information on this subject, see this excellent article by Anne M. Ousterhout and this informative website from Penn State University.

[Featured Image: Painting (1864) of Wyoming Valley by Crospey Jasper Francis. Source: Wikicommons]

5 Comments

Thank you for your fascinating article on a relatively obscure part of American history concerning the Yankee-Pennamite conflict and the Wyoming Valley raid during the Revolution. I have read a number of accounts of the Wyoming battle and agree that it was a very brutal affair with alleged characters such as Queen Esther taking an active role in committing shocking atrocities. In this regard Wyoming was not unique to frontier warfare as attested to by the massacre in Cherry Valley,NY as well as numerous other bloody battles, ambushes and skirmishes such as Minisink Ford under Joseph Brant. What may be unique to Wyoming however is the long brewing resentments built up during the Yankee-Pennamite war and which led directly to the overwhelming retribution and slaughter. I have traveled the Wilkes-Barre,PA area quite a bit and am familiar with the location of Forty Fort. What a desperate time it must have been for all those people knowing that the fight is being lost with no prospect of relief in such a far away place. The command should have remained in the fort – easy for me to say.

Thanks again.

John Pearson

Thanks for the comment! I’m glad you enjoyed the article. It was a fun one to write, though you’re right about frontier warfare.

Thomas – Great article. My ancestor, Captain Jeremiah Blanchard served under LTC Zebulon Butler during the Wyoming Massacre. Do you have any information about a petition sent by the Wyoming Valley settlers to the Connecticut Legislature requesting that body resolve the border disputes with Pennsylvania ? I suspect Jeremiah Blanchard may have signed that document. Thanks.

Thank you for this most interesting and thorough article. One of my ancestors was one of the forty Yankee settlers at Forty Fort, but his wife and family eventually went back to CT and he joined the Rev. War and was killed at Morristown, NJ.

We traveled to Forty Fort and it was fascinating to see my ancestor’s name on the roster of settlers and stand in a place where so much history happened.

Great article! I have read numerous accounts of the battle, but none taking into account the dynamic associated with the history of Pennsylvania/Connecticut conflict. It sheds potential light on my own family history, one branch of which settled Northeastern Pennsylvania in the first decade of the nineteenth century as immigrants from Connecticut.