Dear Mr. History:

What happened with the famous mutiny of the Pennsylvania Line that occurred January, 1781? Did the soldiers have legitimate grievances? What does such a mutiny say about the professionalism of the Continental Army? Sincerely, Miffed About Mutinies

Dear Miffed:

When the soldiers of the Pennsylvania Line mutinied most of them had not been paid in almost a year. A year. I challenge anyone to work any job, let alone endure the harsh life of a Continental soldier that long without pay and not want to kick the bosses to the curb. And the lack of pay was only one of their complaints. So I’ll go out on a limb and say that the soldiers definitely had legitimate gripes. How that fits in with military professionalism becomes apparent after the whole picture is clear.

The story began in November, 1780, when the Continental Army went into winter quarters in camps that were dispersed in New York, Pennsylvania, and New Jersey. The Pennsylvania Line occupied log huts, used the previous winter by the Connecticut Line, on Mount Kemble near Morristown, New Jersey. Major-General Arthur St. Clair, the senior officer of the line, furloughed in Philadelphia, a practice not uncommon for senior officers. The 2,473 Pennsylvania officers and men at Mount Kemble comprised eleven regiments of infantry and one of artillery.

The winter was mild and the huts were about as comfortable as log huts can be, but clothes, food, and pay were in short supply. In mid-December, Brigadier-General Wayne, who was not yet nicknamed “Mad Anthony,” wrote to Joseph Reed, President of Pennsylvania’s Supreme Executive Council, “we are reduced to dry bread and beef for our food, and to cold water for our drink. . . . Our soldiery are not devoid of reasoning faculties, . . . they have now served their country with fidelity for near five years, poorly clothed, badly fed, and worse paid; of the last article, trifling as it is, they have not seen a paper dollar in the way of pay for near twelve months.”[1] Wayne hounded the Executive Council for uniforms and Philadelphians collected both money and winter clothing, but no relief reached the men by the end of December.

Another major issue arose because the Executive Council planned to consolidate several regiments of Pennsylvania Line effective January 1, 1781. Many soldiers had enlisted in 1777 under the somewhat confusing terms of “for three years or the duration of the war.” Focusing on the first clause, “for three years,” some soldiers believed that the reorganization would conclude their enlistments. But the regimental officers focused on the second clause, “or the duration of the war,” and denied the soldiers’ requests for discharge.[2]

Knowing that his men were getting fed up with the situation, the possibility of a mutiny could not have been far from Wayne’s mind. Mutiny was punishable by death under Congress’s Articles of War, but soldiers still chose to rebel against their higher authorities to protest harsh conditions or enlistments. The Continental Army had suffered mutinies since its inception, and Wayne himself faced down two mutinies at Ft. Ticonderoga in 1777. But most uprisings involved small groups of soldiers and were easily dealt with. Wayne sensed trouble, and instead of furloughing at a more comfortable location as he sometimes did, this year he stayed with the men at Mount Kemble.

However, nobody forecasted the magnitude of what was coming on January 1, 1781. It was a clear day and not very cold, “a fine morning. . . the day spent in quietness,” recalled Captain Joseph McClellan of the 9th Pennsylvania.[3] It was Gen. Wayne’s thirty-sixth birthday, but he declined a dinner invitation with a local prominent civilian because he needed to manage the regimental reorganization. The officers of the 10th Pennsylvania held one last dinner together before their unit was broken up. The soldiers received a half-pint of liquor and at about 8:00 PM, troops of the 11th Pennsylvania “began to huzza and continued for some time,” according to Capt. McClellan. Officers quieted the men without incident.[4]

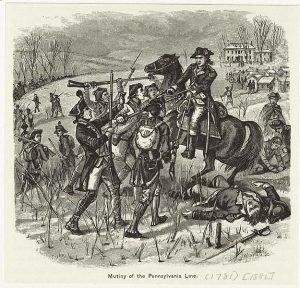

The soldiers were in their huts at about 9:00 PM when another disturbance began among the men of the 11th Pennsylvania. Lieutenant Enos Reeves of the 2nd Regiment investigated and found men gathering in small groups, whispering, and running about. It is not clear what sparked the men to such action, nor is it clear if they even planned to mutiny. But some musket firing began and a skyrocket went into the air. Then soldiers began pouring out of their huts with their muskets and equipment. “I immediately found it was a mutiny,” wrote Lt. Reeves, and he and other officers tried, but failed, to keep the troops in their huts.[5] The column of now mutinous soldiers moved down the line of huts, seized four cannons, fired muskets into the air, and called for more men to join them. Many soldiers hid in their huts until the tumult passed. Mutineers forced the men of the 2nd Pennsylvania to join at bayonet point and fired a few cannon shots over the ranks of the 5th and 9th Regiments to convince them to join the revolt. While the main group of mutineers gathered (or coerced) men, others seized horses, wagons, tents, and provisions. Some officers made fruitless attempts to gain control. In the 4th Regiment, a captain formed a group of soldiers to reclaim the artillery, but the men refused his order to charge. Captain Adam Bettin lunged at one mutineer with his espontoon and the man shot him dead. Two other officers were wounded and more received lesser injuries in the melee. About 1,500 soldiers joined the mutiny, which was over half of the Pennsylvania Line and by far the biggest uprising in the Continental Army yet.

According to Lt. Enos Reeves, Gen. Wayne, Colonel Richard Butler and a party of senior officers arrived at the scene on horseback. Wayne and Butler tried to speak to the men to identify their grievances to no avail. Some of the mutineers fired a musket volley over Wayne’s head, and he opened his coat and told them, “if you mean to kill me, shoot me at once, here’s my breast.” The soldiers replied that they intended no harm to their officers, “two or three individuals excepted,” and moved to depart the camp.[6] Wayne tried to halt them again, but the troops announced their intention to march to Philadelphia for redress on their pay, clothing, and enlistments. In a regulation-perfect column of platoons under the command of their sergeants, the mutineers took the road south towards Princeton. “The men went off very civily,” remembered Lt. Reeves, but he added with a touch of scorn, “to what might have been expected from such a mob.”[7]

Unlike the previous mutinies, the size of this one presented more than disciplinary problems. The Continental Army could ill afford to have so many soldiers exit the ranks. Worse, for all the American commanders knew, the mutinous group could “turn Arnold” and join the British forces that were only about 20 miles away near New York City. Wayne sent two officers speeding to Philadelphia to alert Congress and the Executive Committee and dispatched an aide-de-camp to inform General Washington, who was at the army camp at New Windsor, New York. In his return letter, Washington approved of Wayne’s actions and directed him to identify the mutineers’ grievances for Congress to address. Washington was also concerned that the mutiny could spread to other units and stayed put to keep a lid on things at New Windsor.[8]

Wayne, Butler, and Col. Walter Stewart shadowed the column on the road south. On January 3 the soldiers reached Princeton, New Jersey and set up an orderly camp. A “Board of Sergeants” of one man from each regiment presented Wayne with their main complaints; 1) that eligible soldiers be discharged, 2) the soldiers should receive all their pay due in hard cash, and 3) they receive decent clothes and provisions. Wayne considered the demands reasonable but told the sergeants that only civil authorities had the power to address the issues.

On January 6, Pennsylvania’s Joseph Reed arrived at Maidenhead, now known as Lawrenceville, six miles south of Princeton and began meeting with Wayne and the Board of Sergeants. A special committee of Congress, appointed to oversee negotiations, went to Trenton. The Pennsylvania Line’s senior officer, Gen. St. Clair, cancelled his furlough and took command of the soldiers at Mount Kemble that did not join the mutiny. Reed, Wayne and the Board of Sergeants negotiated over the next few days, sometimes testily. For one thing, Wayne and Reed clashed over their respective roles. And according to Reed, the president of Board of Sergeants, John Williams of the 2nd Pennsylvania, was “either very ignorant and illiterate, or was drunk,” and communications with the Board was sometimes confusing.[9] The fiery Wayne was not known for his patience, and his sympathy for the mutineers wore thin.

The British also got involved. General Sir Henry Clinton learned about the mutiny on January 3 and sent three men to skulk into the camp at Princeton “with offers of protection and pardon and full liquidation of all their demands” in return for their allegiance. [10] Clinton also moved Hessian grenadiers and jagers to Staten Island to march into New Jersey if an American vulnerability developed. The mutineers were having none of it; they captured one operative, John Mason, and his guide, James Ogden, and held them prisoner during the negotiations.

On January 8 Reed and the Board reached an agreement; a committee would review the enlistment of each soldier and discharge those eligible. Also, the men would receive proper uniforms as well as warrants for their back-pay that Pennsylvania would honor as soon as it could raise the money. The next day, the mutineers marched to Trenton to begin executing the settlement’s provisions. The mutiny was over, but not fully resolved by a long shot – more on that later.

The mutiny was a wake-up-call to the Pennsylvania Line on its lack of professionalism, but the offenders were the officers, not the enlisted soldiers. Except for the violence on January 1, the mutineers conducted themselves with an impressive level of discipline. They kept a strict military camp at Princeton and gained the support of the local population. The soldiers also promised to fight under Wayne in the event of an enemy attack. And as soon as the negotiations ended the sergeants handed Mason and Ogden over to the Congressional committee, an act that Gen. Washington called, “an unequivocal and decided mark of attachment to our cause.”[11]

The big problem was that the regimental officers in the Pennsylvania Line followed some pretty poor leadership habits. At Princeton Reed learned that the men held “a strong aversion to many of their former officers,” Wayne and the brigade commanders excepted.[12] The overseeing Committee of Congress also reported that the soldiers anger was “chiefly against some of their own officers and complained of fine deception in their enlistments,” and recommended “the inferior officers” receive leadership instruction to “temper severity with mercy” “(though both statements were crossed out of their final report).[13] Historian Charles Royster concluded in A Revolutionary People at War that the regimental officers in the Pennsylvania Line imitated Gen. Wayne’s “gaudiness, arrogance and harshness” but failed to emulate his genuine care and respect for the soldiers. The result was years-long hostility between the officers and men that flared into mutiny.[14]

Put yourself in the shoes of the soldier. You haven’t been paid in months. Without too much complaint you’ve endured at least three years of brutal battles, harsh discipline, and deplorable conditions. You and your family need money. Then the planned reorganization leads you to believe that your three year enlistment is up. But your own officer, the same one who has treated you poorly over the past three years, says “Sorry. You actually enlisted for the entire war, so stick around. And don’t forget to clean the latrines tomorrow.”

I’m joking here. All of the officers were certainly not deadbeats. They served courageously in the same battles, harsh conditions and the lack of pay along with the men, and many surely took great care of their soldiers. The mutiny genuinely shocked and insulted many officers. And the soldiers, who were no saints, were probably guilty of reading their enlistments exactly the way they wanted to. The government of Pennsylvania was responsible for clothing and paying the soldiers, so that body also bears some responsibility for the circumstances that led to mutiny. Overall, the collective leadership of Pennsylvania allowed conditions to become so bad, so unendurable, that over a thousand men chose mutiny and a possible death sentence as their only recourse to get what they thought they deserved.

Now let’s see how all the parties finally settled the mutiny. The former mutineers arrived at Trenton on January 9. Over the next week a committee reviewed enlistments, taking the men at their word about their enlistment dates, and discharging soldiers who claimed eligibility. The soldiers also received shirts, shoes, blankets, woolen overalls and fifty Pennsylvania shillings, the equivalent of a month’s pay. Almost the entire Pennsylvania Line went on furlough for sixty days. None of the mutineers received punishment. At the end of January Wayne reported to Washington the discharge of 1,220 soldiers, leaving the Pennsylvania Line with 1,180 sergeants and privates.[15] Washington thought that some of the men lied to get out early.[16] Recruiting efforts began soon and many men re-enlisted for a bounty of nine Pennsylvania shillings.

A court-martial convicted Gen. Clinton’s emissaries Mason and Ogden of spying and sentenced them to death. Mason was a Loyalist freebooter toughened to the risks of war and accepted his fate. Ogden, on the other hand, was only a Loyalist citizen who Mason hired as a guide, and he was stunned that the court found him guilty of any crime. On January 11, near Summer Seat, Pennsylvania, across the Delaware River from Trenton, they both swung from nooses made of rope unwound from a horse collar and thrown over a tree limb. The hanging site was at a crossroads and their bodies turned in the cold wind for days afterward, visible to all who rode by.

What lessons the military and civilian leadership learned from the mutiny is unclear. The state of Pennsylvania and Congress strived throughout the spring of 1781 to raise money, but could only pay the men with state money that was about 1/7 the value of specie. Wayne prepared his men to take the field in March, but he still had to harangue Pennsylvania for money, and he told Washington “the same supineness and torpidity that pervades most of our civil councils have prevented any part of the troops from moving.”[17] Some things never change.

In May some of Wayne’s men mutinied again, and this time the consequences were brutal. But that’s another story.

There is much more to this interesting and complicated case. To read more, check out the well-researched Mutiny in January, by the eminent writer and biographer Carl Van Doren.

[1] Wayne to Joseph Reed, December 16, 1780, Life and Correspondence of Joseph Reed, Military Secretary of Washington, at Cambridge, Adjutant-general of the Continental Army, Member of the Congress of the United States, and President of the Executive Council of the State of Pennsylvania, (William B. Reed, ed., Philadelphia, Lindsay and Blakiston, 1847 ), 316.

[2] Robert K. Wright Jr., The Continental Army, (Washington, D.C., Center of Military History, 1983, reprint, 2000), 163; and Carl Van Doren, Mutiny in January: The Story of a Crisis in the Continental Army now for the first time fully told from many hitherto unknown or neglected sources both American and British, (New York: Viking Press, 1943), 35.

[3] “Diary of the Revolt of the Pennsylvania Line, January, 1781,” in Pennsylvania Archives, Second Series, Volume XI, (Harrisburg: Lane S. Hart, State Printer, 1880), 631.

[5] Letter 143, “Extracts from the Letter-Books of Lieutenant Enos Reeves, of the Pennsylvania Line (continued),” John B. Reeves, ed., The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography, Vol. 21, No. 1 (1897), 73.

[8] Washington to Wayne, January 3, 1781, The Writings of George Washington, Volume 21, accessed January 5 2014, via: http://web.archive.org/web/20110220004025/http://etext.lib.virginia.edu/etcbin/toccer-new2?id=WasFi21.xml&images=images/modeng&data=/texts/english/modeng/parsed&tag=public&part=66&division=div1.

[9] Reed to the Committee of Congress, January 8, 1781, Life and Correspondence of Joseph Reed, 329.

[10] Sir Henry Clinton, The American Rebellion: Sir Henry Clinton’s Narrative of His Campaigns, 1775-1782, with an Appendix of Original Documents, William B. Willcox. ed., (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1954), 241.

[11] Washington to Nathaniel Greene, January 9 – 11 1781, Writings of George Washington, Vol. 21, accessed January 7 2014 via: http://web.archive.org/web/20110220004533/http://etext.lib.virginia.edu/etcbin/toccer-new2?id=WasFi21.xml&images=images/modeng&data=/texts/english/modeng/parsed&tag=public&part=94&division=div1

[13] Journals of the Continental Congress,1774-1789, Volume XIX, January 1 – April 23, 1781, (Washington, Government Printing Office, 1912), 80, 83.

[14] Charles Royster, A Revolutionary People at War: The Continental Army and American Character, 1775-1781, (University of North Carolina Press, 1979), 304.

[15] Wayne to Washington, January 28, 1781, George Washington Papers at the Library of Congress, accessed January 4 2014 via: http://memory.loc.gov/cgi-bin/ampage?collId=mgw4&fileName=gwpage074.db&recNum=756

[16] Washington to St. Clair, February 3, 1781, Writings of George Washington, Vol. 21, accessed January 9 2014 via: http://web.archive.org/web/20110220011058/http://etext.lib.virginia.edu/etcbin/toccer-new2?id=WasFi21.xml&images=images/modeng&data=/texts/english/modeng/parsed&tag=public&part=191&division=div1

15 Comments

What an excellent, balanced account! You will follow this piece with another on the New Jersey mutiny, right Michael? Unfortunately, the two go hand-in-hand, with each side drawing different conclusions from the PA experience.

I’m very glad you liked the piece Ray! I am considering another on the New Jersey mutiny because they certainly are linked, as you mention, as well as others. Many mutinies of varying scope occurred throughout the Revolution, and the events speak volumes about the Continental Army. Many thanks – Mike

I’ll look forward to chapter 2. Thanks!

I thoroughly enjoyed this. Well done. I hope you explore other mutinies in the (near) future.

John Nagy had a good book called Rebellion in the Ranks that dealt with a lot of the mutinies, I am almost finished reading it, but it could be a good look for some more stories of these mutinies.

Truly an excellent article. The spy part was something I had not read before. It is interesting how spies were dealt with in the conflict. Mercy was not an option it seems.

Thanks a ton Jimmy! The story of Mason and Ogden is certainly interesting. Clinton was seriously wrong in his belief that the mutineers would come over to the British side, which is not out of character for him – Clinton often saw signs from the Americans exactly as he wanted to see them. The concept of bringing over such a large group of men was powerfully compelling, so he gambled. Mason and Ogden payed the price. But Mason was only one of at least three “emissaries” that Clinton sent into the sergeants’ camp. One wonders what happened to the other ones – or if they ever took another mission again, after the fate of Mason and Ogden. Mike

Another great article, Mike! Thanks for providing such a balanced and interesting account of what went on. Looking forward to your next column.

Carl Van Doren got four of the spies in the Pennsylvania Line Mutiny correct but guessed at two and got them wrong. I identified the other two spies and back it up with references in my book Rebellion in the Ranks, Mutinies of the American Revolution. I cover 115 mutinies during the war and there are 30 spies involved with the mutinies. If you like the subject of mutinies, it is the only book that covers the subject for the entire war. If you have any questions just ask. John A. Nagy

Thanks John, that’s very interesting. I’ll address the mutiny of the New Jersey Line next and will be sure to refer to Rebellion in the Ranks. Mike

Great book John, as I noted in the comments above. I enjoyed it and recommended it! Thanks.

Hello. I am researching my 5th great grandfather who is listed on the York County (PA) Muster Roll of the 4th Company for the Spring of 1785. The following officers are shown: Captain Martin Will; Lieutenant Henry Shift, and Ensign Jacob Verner. I am trying to understand what roll the privates held. My 5th great grandfather’s veterans burial card shows ‘no service time.’ I am still searching for the supply tax, which, from what I understand, might qualify him as a Revolutionary War Patriot. Any leads to where I look next is much appreciated.

I will be co-presenting a paper on the mutiny in March 2020. I have had the good fortune to work on a archealogy project on the area of the occupation of the PA line and found evidence of where the cannon were fired. More to come! A third year of work coming this late spring!

Thank you. I had ancestors and relations who were a part of this mutiny.

Please do follow up on the New Jersey mutiny!