Even as late as the spring of 1783, there was still a war on. A substantial number of British troops were in New York City and the surrounding area, and Continental troops continued to hem them in. But peace and disarmament were near at hand. Among the soldiers with peace on his mind was a young trooper in Colonel Sheldon’s 2nd Dragoons, a cavalry regiment raised in Connecticut that had served with distinction for the entire war.

Even as late as the spring of 1783, there was still a war on. A substantial number of British troops were in New York City and the surrounding area, and Continental troops continued to hem them in. But peace and disarmament were near at hand. Among the soldiers with peace on his mind was a young trooper in Colonel Sheldon’s 2nd Dragoons, a cavalry regiment raised in Connecticut that had served with distinction for the entire war.

Nathaniel Baldwin Woodruff of Litchfield had enlisted in the regiment in December 1779, a month before his seventeenth birthday. By May of 1783 he was a veteran soldier with three things on his mind: peace, home, and a young woman named Bede Barns. They had met when Woodruff and some fellow troopers had “staid & had their horses kept for a few days at Meriden” where she lived. Although recorded as a private soldier when he enlisted, family tradition had it that “the first time she ever saw [him], he was on horseback with a trumpet in his hand.” They were smitten with each other, but duty called; Woodruff rode off with this comrades to continue patrolling the lines. When he learned that the regiment was soon to be reduced and his discharge was imminent, he joyfully conveyed the news to Bede:

Sublime Lady

Having an opportunity to send Direct to You I shall Employ the same with the Greatest Pleasure immaginable, just to acquaint you of my Health & Wellfare hoping that these may find you in the full Enjoyment of Yours. I have no news to write. Perhaps more than you have heard. But I have the greatest Reason to think that the army will Be Discharged in Twenty or thirty Days from this. Mr. Orton Came from Camp Last Thursday & informed me that we were to Be Discharged By the twentieth of June which will Be the Happiest Day that Ever I enjoyed if so be it is true. & then you must hope for a visit from me immediately as soon I obtayn an honorable Discharge from this Bloody War Which I have so long Been obliged to submit to and suffered the hardships & cruelties of so many Disagreeable Campains overjoyed at Last to meet the happy Day wherein we shall Quit the field With honour after having set our Country at Liberty from a hard and Cruell tyrant master; then shall i fly in Peace and Lodge myself in the arms of my Dear & shall never Be at Rest till i am safely arrived within your Pleasantness happy will this opportunity Be When I shall have the Pleasure of the full enjoyment of that Lovely Person which i so much admire and Have so Long strove to obtain. How solitary the month of may hath appeared to Me although it has deckt the fealds and meadows with all the gay flowers It Could Yeald & Cloathed the Lofty trees and Pleasant Gardens with the sweetest of Blossoms But all these Could yeald me no Delight for I was absent from my only Dear

Hear I must Quit With subscribeing myself Your true, But Absent Lover – Nathaniel B. Woodruff

Danbury May 31st ‘83

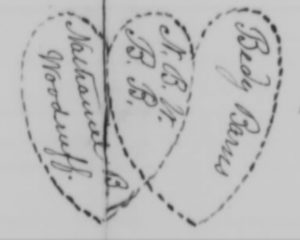

Woodruff’s information, delivered with vivid passion, proved to be inaccurate but in a favorable way: he and most of the 2nd Dragoons were discharged less than two weeks later, on 12 June 1783. He returned to his home town, from where he continued to woo Bede Barns. On 15 July, he sent her a “poetical present” with the title “A Present from Nathl. B. Woodruff of Litchfield to Bedy Barns of Meridan, Wrote at Litchfield July 15th 1783.” It was a special type of poem called an acrostic, in which the first letters of each line spell out another message – in this case the symbolically bringing together the names of the poet and his intended. In the middle of the page he drew a pair of entwined hearts bearing their initials; on the left side he wrote six quatrains neatly revealing his name in the initial letters. The two stanzas on the right were built on her name; being shorter, he filled the right half of the page with additional verses about the war’s favorable outcome and reinforced his intentions for the two of them.

A Crostick

1st. Now I Have Wrote Your Name and mine

And see My Heart is Link’t With thine.

There I Have fixt them Both for one

Heavens Grant it Shortly may Be Done2nd Another mans You Cannot Bee

No Love Your Heart You Gave to me

I shall Enjoy You for my own

Ere Long we’ll Both of Us Be one3rd Lovely and happy Day twill Be

Blesedest Hour that Ere I see

And Shurely it Cannot Be Long

Love till this Happy Day Comes on4th Dear marm in free from Wars alarms

With gayety I’ll fly to Your arms

Into the same myself I’ll throw

Nothing Can Pleas my fancy so5th With Glory and honour renownd

Our Little empire we have Crown’d

Old england When sent ore their troops

Did mean to Burn this Empire Up6th Rejoyct to think we’v Gaind the Day

Unto my Love now I’ll away

For She’s the Girl thats kept my heart

from her till Death I’ll never Part7th Blest happy morn the wars adue

Ere long I’ll Come and marry You

Desirous to enjoy my Dear

You are my joy and Chiefest Care8th Be you to me as kind and true

As I my Dear have Been to You

Receive my heart within your Breast

Ner’e to remove nor it molest

So in Pleasure Let it Rest9th Farewell, You Cruel War adue, Peace Doth Return once more

Proud tyranick troops are Cald again to Britans Shore

Declaring Independence unto, the United States

Which is all America Doth Crave, for Slavery she hates10th Now iv’e Returnd to my Sweetheart and she’s Been true to me

I’ll nere to her Decitful Prove But married we will Be

And I’ll enjoy my Loving Bride that’s so long Kept my heart

You are the Person that i’ve Chose from You I’ll never Part11th Pleas to Excuse these Crooked Lines and Bad Composure too

And Be so Kind as to Except this Preasant int for You

And then my Person I Will Give to You Miss Bedy Barns

With Harmony Will spend our Lives in Loves most Sweetest Charms12th What Happiness shall we Injoy When we are Man and Wife

May God increase our joys and send A Long and happy Life

I hope my Dear twill Not Be Long until the Nott is tied

When I Your happy husband Be and You my Lawful Bride

Woodruff’s poetry was doggerel, but impressive enough for a farm boy from Connecticut. It didn’t win him a place in the annals of literature, but it did win him a bride; he and Bede were married before year’s end.

Their life together may have been as joyous as they’d hoped; in February 1786 their daughter Abigail was born. The union was tragically short, though – Nathaniel Baldwin Woodruff died on 7 May 1788, only twenty-six years old. How this impacted Bede is not known, but with a young daughter’s welfare to consider, she did the sensible thing and remarried three years later. Her second husband died in 1819; she lived for another twenty years, passing away on 3 April 1839 at seventy-five years of age.

It is through Nathaniel and Bede’s daughter Abigail that the letter and the poem survive. In 1838, Congress passed an act allowing pension benefits for widows of soldiers who served in the American Revolution. Ten years later Abigail learned that, because her mother had been alive when the widow’s pension act was passed, she could claim the balance of those benefits from the date of the act until her mother died; she submitted an application. Although her mother had told her stories about her father as a handsome young soldier, the only documentary evidence she possessed was the 1783 letter and poem. These contained enough evidence of his military service to be corroborated with muster rolls and depositions of others; although Nathaniel Woodruff had been unable to provide for his daughter when she was young, his service ultimately secured her a small financial reward late in her life. Among the deponents in her favor was her own son who had become a bugler in the cavalry, and said that his grandmother Bede had often remarked that he had the same features as his grandfather, Nathaniel Baldwin Woodruff.

[The information above is from the pension application and supplementary documents submitted by Abigail (Woodruff) Danks. Cataloged as Revolutionary War Pension W. 14, 926 (National Archives, Washington, DC), the file includes the letter and acrostic poem as well as Abigail’s and other depositions. The spelling and capitalization here is as true to the original as possible, with the exception of “I’ll” which Nathaniel Baldwin Woodruff wrote “ill’e”. Punctuation is almost nonexistent in the manuscript letter; Woodruff relied mostly on new lines and spacing to denote sentence breaks. Readers are encouraged to refer to the original documents, images of which are available on microfilm through the United States National Archives or www.fold3.com, rather than relying solely on the transcripts presented here.]

One thought on “A Dragoon a-Wooing”

The more I read the more it seems that pension applications are good sources of personal histories. This is a very touching one that reminds how very human and similar to us our colonial ancestors were. Thanks for a fascinating look into the heart of one dragoon.