THE TRIAL THAT GRIPPED THE NEW NATION

The Grand Jury in Richmond determined that there was ample evidence of George Wythe Sweeney’s guilt. Virginia attorney general Philip Norborne Nicholas would be prosecuting the murder trial against Sweeney. The talented 31-year old prosecutor was the product of a highly influential family in Virginia who helped to get their native son, Thomas Jefferson, into the White House. With all of the damning evidence in this case, it was pretty well assured that prosecuting the no-good Sweeney for the murder of the famous and beloved George Wythe would be like shooting fish in a barrel.

Former High Chancellor William Wirt, aside from being the governor’s brother-in-law, volunteered to be one of Sweeney’s defense attorneys. It would be a nicely republican notion to say that the reason Sweeney received competent defense lawyers is the concept that everyone in America should receive a fair trial. But that wouldn’t be true in this case. Wirt, who cured his own childhood stuttering through sheer will power, needed the dollars and legal publicity that winning Sweeney’s acquittal would bring.

The second high-power attorney who signed onto the Sweeney Defense Dream Team was ex-Virginia governor and former United States attorney general and secretary of state Edmund Randolph. Randolph also needed the legal boost in status that an acquittal would bring. He had been forced to resign his secretary of state cabinet office by none other than President George Washington through an alleged bribery scandal. Randolph was later accused of not being able to account for the sum of $49,000 while holding that office and was ordered to repay the amount. On the Sweeney case, both Wirt and Randolph would have to work together to formulate Sweeney’s defense. The interesting point in that angle is the fact that Wirt and Randolph intensely hated each other.

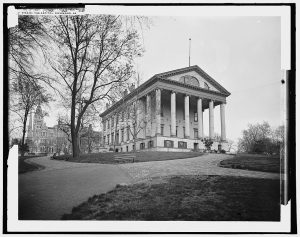

The much-publicized murder trial of George Wythe Sweeney started on September 2, 1806.[19] For each blockbuster piece of evidence attorney general Nicholas laid out to the jury, the team of Wirt and Randolph skillfully offered a deflection:

- The trio of imminent doctors could not swear beyond a reasonable doubt the cause of George Wythe’s death;

- Sweeney was known to be possession of “rats bane” (arsenic), but so was half the population of rat-infested Richmond;

- The arsenic-laced paper that Sweeney had thrown over the jail yard wall matched the arsenic-tainted paper found by DuVal in Sweeney’s room, yes. But that fact would be inadmissible. You’ll find out why.

- Sweeney was caught forging his granduncle’s name on checks, yes. But that accusation and trial was separate from the murder trial. The two incidents were declared non-related.

- Sweeney’s portion of his inheritance was shown to first be shared, then lessened, and then completely cut from Wythe’s will. But it was declared that this same occurrence happened all the time in families everywhere and wasn’t the cause of murders;

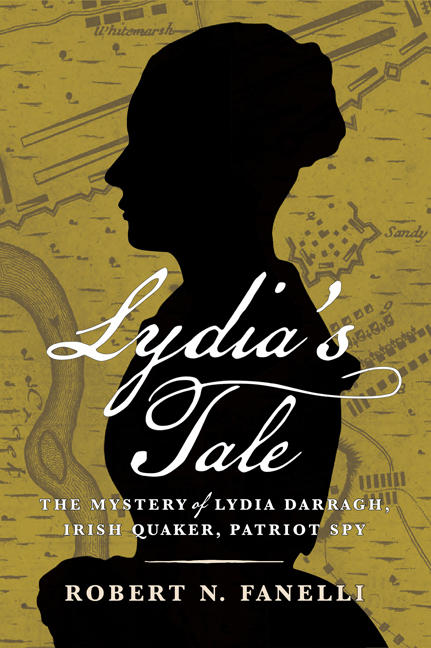

But the best piece of explosive testimony would be coming from the household eye-witness – Lydia Broadnax. It was Broadnax who observed Sweeney secretly reading Wythe’s will and later putting arsenic into the morning coffee pot and quickly leaving the house. Broadnax knew of Sweeney’s forgery episodes and the clashes those cases brought on between Wythe and Sweeney. She knew of Sweeney’s theft of Wythe’s valuable books, documents, and artifacts which Sweeney stole to repay his huge gambling debts. However, Lydia Broadnax would never be able to testify to those observations in criminal court. The jury would never hear those facts. Lydia Broadnax was black.

Virginia state law prohibited a black person from testifying against a white person in any county, local or state court. Even if the incriminating details were told by the black person to a white person (such as in the case of Pleasant finding the arsenic and paper near the jail wall and telling the white jailer), the evidence was declared “hearsay” and was inadmissible.

On September 8, 1806, the jury in the George Wythe Sweeney murder case deliberated for less than an hour and returned to the courtroom with the verdict of not guilty. Sweeney was innocent of the murder of his granduncle in the 1806 eyes of Virginia law. A few years ago Dan Berexa, a Nashville attorney and historian, brought an additional modern day angle to the jury’s innocent verdict. Reading into the psychology of the jury, Berexa wrote, “It is also reasonable to conclude that Randolph’s mere involvement as Sweeney’s defense counsel influenced the jury toward acquittal … A jury, not knowing Randolph’s real motivations, may have concluded that Randolph would not have accepted the defense of Sweeney unless he believed the young man did not kill his good friend and client.”[20]

But Nicholas wasn’t through with Sweeney just yet. The day after Sweeney’s acquittal, the prosecutor decided Sweeney should stand trial for forgery.

SWEENEY’S TRIAL NUMBER TWO

Philip Norborne Nicholas considered Sweeney’s forgery trial a more simplified slam-dunk case and was reassured that at least Sweeney would spend some time behind bars, regardless of what he was found guilty of. Sweeney’s attempt at forging George Wythe’s signature wasn’t even close. The two completely different signatures were shown to a jury. It was clear to everyone in the courtroom that this was a case of forgery. The testimony from the (white) Bank of Richmond executives put Sweeney in the bank, seven times, cashing obviously forged checks. Sweeney was found guilty of forgery. But it wasn’t over yet.

William Wirt was astute enough to know the intricate details of Virginia law. He knew that the forgery laws on the books at that time only pertained to personal forgery, meaning between two people only. In 1789 when the existing personal forgery laws had been written, the rise of public banks had not occurred yet in Virginia or throughout the new United States. Sweeney had forged bank checks and there was no public forgery law on the books. A bank was not a person. Sweeney in reality, Wirt explained to the court, had been accused of breaking a law that didn’t exist. Filing an appeal to the guilty charge, Wirt said the court had to find Sweeney innocent and the court agreed.

So George Wythe Sweeney was found not guilty of both murder and forgery in courts of law. Sweeney was surprised and elated. The general public however was outraged and swore revenge on Sweeney. On advice of counsel, Sweeney was told to get out of town fast and never come back! He did just that.

THE SORDID AFTERMATH

There are sketchy records that Sweeney took off for the relative wilderness of Tennessee, where his own personal values again kicked in. He was apparently arrested and convicted for stealing a horse and spent a few years in prison. Bruce Chadwick, the author of “I Am Murdered”, said he did an intensive investigation to find out what happened to Sweeney upon his prison release, but came up empty. Sweeney appears to have disappeared into the pages of history.

The medical practice of the three indecisive doctors soared following the trial, and all three went on to exalted high positions within the medical community.

In another example of history’s ironies, President Thomas Jefferson (close lifelong friend of Wythe) named William Wirt chief prosecutor in the 1807 treason trial against Aaron Burr. Wirt went on to be appointed to the position of United States attorney general under presidents Madison, Monroe, and John Quincy Adams – which makes Wirt the longest serving attorney general in U.S. history.

Wirt’s arch-enemy, Edmund Randolph, defended Aaron Burr in that same treason trial that Wirt prosecuted. Through a federal law technicality, a tactic both lawyers used effectively, Burr was found not guilty by Supreme Court chief justice John Marshall – who had been one of George Wythe’s promising young students. Randolph’s career reignited as he’d hoped, and he grew a legal clientele list again in the last part of his life. Randolph died about six years after the Burr trial and had pretty much won back his reputation. But the missing $49,000 debt that Randolph owed wasn’t erased by the American government with his death. The Randolph family had to keep paying on it and it wasn’t fully paid back until 1858.

Lydia Broadnax continued to live in Richmond until her death most likely in 1827, the year that her will was probated. In Lydia’s will was listed a small house on a Richmond lot. She had to sign her 1820 will with an “X” because of the damage the arsenic had done to her eyesight over the 14 year period. On April 9, 1807, shortly after Wythe’s death, Broadnax had written to President Thomas Jefferson in her own handwriting appealing for “some charitable aid” saying, “being almost intirely deprived of my eyesight, together with old age and infirmness of health I find it extremely difficult in procuring merely the daily necessities of life – and with-out some assistance I am fearful I shall sink under the burden.”[21] According to editor-author Jack McLaughlin, “Jefferson sent Broadnax fifty dollars, but not directly. He instructed his Virginia agent – a cousin, George Jefferson – to forward the money for him … Jefferson was careful about writing directly to women during his presidency for fear the mail would be opened enroute and his privacy compromised. This was particularly true in a sensitive case like the Wythe murder with its unanswered questions about why he would leave much of his estate to a black woman and a mulatto boy.”[22]

What McLaughlin may have been alluding to was malicious gossip that was whispered even during George Wythe’s time. The gossip was raised again in 1974 by Fawn Broadie who stated in her book that the obvious reason a wealthy old man would leave his estate to an ex-slave woman and a mulatto boy was that Broadnax had been Wythe’s mistress and Michael Brown had been their illegitimate son.[23] But this base theory has since been dismissed by serious scholars. The records show that when Michael Brown was born in 1790, Lydia Broadnax was 50 years old and probably not able to have children. Additionally she was never listed as the mother and slaves usually kept the master family’s last name, but the “freed boy” had the different last name of Brown. The fact that Broadnax had stayed on in the household being a paid housekeeper for Wythe after being freed had in fact been her choice, which possibly says quite a bit about Wythe’s kindness. That along with the fact that Wythe had long been known to tutor promising white and black teens alike would also explain Brown’s presence. Finally, after reading many of Wythe’s letters and even his versions of last wills, you would discover quite strikingly that Wythe was very religious. That alone would never mean a possible dalliance in the case of someone else. But in Wythe’s case, one would guess that ol’ George would never mess around, even after the death of his second wife, because of the morality of it all.

The Virginia laws on personal vs. public forgery were quickly updated as a result of the Sweeney trial. And what of the law prohibiting blacks from testimony against whites? Amazingly it would stand for quite a while. “The Virginia rule of law prohibiting the testimony of blacks in cases in which whites were parties would not be cast away until shortly after the conclusion of the Civil War.”[24]

Although the words on George Wythe’s gravestone read like a bullet list of his accomplishments, perhaps the best epitaph can be found in the words of the Founding Era’s poet and George Wythe’s friend and student, Thomas Jefferson. Jefferson simply called Wythe “my late master and friend.”[25] In 1820 and nearing the end of his own life, Jefferson made a final reflection on his master and friend: “No man has ever left behind him a character more venerated than G. Wythe, his virtue was of the purest tint; his integrity inflexible, and his justice exact; of warm patriotism, and, devoted as he was to liberty, and the natural and equal rights of man.”[26]

- The actual District Court records of the Sweeney murder trial were burned up during the Richmond evacuation fire at the end of the Civil War. However the Hustings Court (Hustings Courts were like local county courts) records are the grand jury summary papers and they survived. They are housed at Colonial Williamsburg.

- Tennessee Bar Association, “The Murder of Founding Father George Wythe,” http://www.tba.org/journal/the-murder-of-founding-father-george-wythe (accessed November 17, 2013).

- Jack McLaughlin, ed., To His Excellency Thomas Jefferson – Letters to a President (New York, NY: W.W. Norton & Company, Inc., 1991), 128.

- McLaughlin, ed., To His Excellency Thomas Jefferson, 127-128.

- Fawn M. Broadie, Thomas Jefferson: An Intimate History (New York: W.W. Norton & Co., Inc. 1974), 390-91.

- Tennessee Bar Association, “The Murder of Founding Father George Wythe”, http://www.tba.org/journal/the-murder-of-founding-father-george-wythe (accessed November 17, 2013).

- The Library of Congress, The Works of Thomas Jefferson in Twelve Volumes. Federal Edition. Collected and Edited by Paul Leicester Ford; Thomas Jefferson to John Tyler, November 25, 1810, http://memory.loc.gov/cgi-bin/query/r?ammem/mtj:@field(DOCID+@lit(tj110077)) (accessed November 10, 2013).

- The Library of Congress, The Thomas Jefferson Papers Series 1. General Correspondence. 1651-1827, Thomas Jefferson, August 31, 1820, Biographical Notes on George Wythe, image 217 http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.mss/mtj.mtjbib023877 (accessed November 10, 2013).

2 Comments

Mr. Smith, thank you so much for writing such a poignant, accessible story on the life and times during the this complicated era. Living here in Virginia and being a a voracious consumer of American history, this side line of what was going on in the everyday life of our forefathers, really brings the past into an perspective. It is this type of storytelling that helps the everyday, common reader feel connected to our amazing country. I cant wait to read your entire book!

It’s unfortunate that colonial trials, civil and criminal, escape notice of many historians so this is a very welcome article. Reading about Sweeney’s escapes from the jailer or hangman felt like someone drawing their fingernails across a blackboard but as a lawyer it was interesting to see how certain evidentiary decisions were made, similar or the same way they’d be made today. How reassuring it is to see that not 20 years after ratification, the Constitution’s protections were already well at work.