George Wythe was about the last person anybody would ever want to murder. At age 80, Wythe was an exceedingly kind and generous man who could be seen ambling down the streets of Richmond, Virginia in that year of 1806. The townspeople loved him, “His countenance was exceedingly benevolent and cheerful …”[1] and “He moved with a brisk and graceful step.”[2] “In an era when most men died before they reached their fiftieth birthday, the sight of the frail, balding happy justice, paddling down the streets of Richmond with a well-worn law book or two under his arm, was reassuring.”[3] Even John Adams liked Wythe, and that’s saying something. Dr. Benjamin Rush said that Wythe had “dove-like simplicity and gentleness of manner.”[4] George Wythe’s temperament was a little like Ebenezer Scrooge at the end of “A Christmas Carol.” Why, he even looked a little like how Ebenezer Scrooge was described by Dickens. Chancellor George Wythe was the last person anyone would target to be killed. But he was.

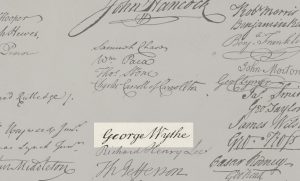

George Wythe (pronounced “with”) wasn’t just any local judge. Wythe’s life had already been one of distinguished service and historical precedence. Schooled by his mother, he taught himself law and passed the state bar at age 20. He eventually started his own law firm, was elected to the House of Burgesses, and notably became the first law professor in American history instructing at the College of William and Mary. He taught law to many promising students such as James Monroe, John Marshall, and Henry Clay. But one of his brightest students was a tall, thin red-headed kid who played the violin named Thomas Jefferson. The childless Wythe and fatherless Jefferson struck up a strong bond that lasted until the end. Jefferson was Wythe’s pupil for four years, law clerk for five years, and even lived with Wythe and his wife in their Williamsburg home. The two served together as Virginia delegates to the Second Continental Congress and both signed the Declaration of Independence, the first signature space of the Virginians being reserved for Wythe. Their bond of friendship was so strong that Jefferson gave Wythe his first draft of the Declaration of Independence. Jefferson said of Wythe, “a purer character has never lived.”[5] Wythe was also a delegate to the Constitutional Convention and in 1788 convinced the new state of Virginia to ratify the United States Constitution. Wythe was also a gentle, giving person who liked to tutor young protégées regardless of race or social status. “He and his wife boarded young students and may have even paid for some of the poorer students’ legal education.”[6] But all was not well in the aging George Wythe’s life.

By 1789, Wythe’s second wife had died and his commute from Williamsburg to Richmond for his job as chancellor in the Virginia Court of Chancery was getting to him, so Wythe packed up and moved to Richmond. But just before the move Wythe, who was becoming increasingly abolitionist in his feelings, freed many enslaved persons that he could legally manumit. One particular ex-slave decided to stay with Wythe as his maid and housekeeper, 66-year old Lydia Broadnax. Also moving with Wythe and Broadnax was a 16-year old freed mulatto boy named Michael Brown. Brown was a bright young man to whom Wythe was teaching Greek and Latin. George Wythe, ever the life-long learner, also had sought out the Jewish community when he reached Richmond so even he could begin learning a new language – Hebrew! “This was his seventh language, for he already could read English, French, Italian, Spanish, Latin and Greek.”[7] Wythe was so fond of Broadnax and Brown that he had included them in his will to inherit his sizable fortune.

Wythe had also felt very sorry for his sister Anne’s misfortunes and in 1803 offered to include her troubled grandson, 18-year old George Wythe Sweeney, in his will as well.[8] Within two years however, Wythe’s problematic grandnephew had moved into Wythe’s Richmond hilltop household he shared with Broadnax and Brown. In 1806 Richmond was going through a huge crime wave centered around its race tracks and composed of gambling, cons, prostitution, murders and alcohol.[9] Young George Wythe Sweeney was very attracted to this sordid environment and started secretly stealing and selling his granduncle’s rare books and historic documents to pay off his growing gambling debts. Then he started forging checks, six checks in fact, on George Wythe’s bank account. Each time Sweeney was caught, kindly George Wythe declined to prosecute his grandnephew, hoping maturity would soon kick in and Sweeney would straighten his life out. However one night in May 1806, Lydia Broadnax happened to see Sweeney reading Wythe’s will that stated upon Wythe’s death, the fortune was to be divided into thirds – to Broadnax, Brown, and Sweeney. But the will also stipulated that should Broadnax and Brown die, the entire estate would go to George Wythe Sweeney. Sweeney put the will back into the drawer and closed it. Broadnax thought no more about it.

COFFEE AND ARSENIC

Sunday morning, May 25, 1806 was just like any other weekend morning in the Wythe household. After George Wythe rose, he took his usual wake-up shower in his homemade shower unit out back using freezing well water (a habit that may have rubbed off on Jefferson). Then instead of heading off to the courthouse, Wythe went back up to his bedroom to read newspapers while Broadnax prepared a breakfast of eggs, toast and coffee downstairs. George Wythe Sweeney bounded into the kitchen and announced to “Aunt Liddy” Broadnax and Michael Brown that he was in a hurry and only had time for toast and coffee. Sweeney poured himself a cup making sure Lydia saw what he was doing. Then Broadnax noticed that Sweeney put the coffee pot back on the kettle above the fire, “and quickly moved his hands over its top.”[10] She then saw Sweeney toss a piece of paper into the fire as he chomped his toast and slurped up his coffee, making noise to show he had finished the cup before he left the house.

While Brown drank his cups of coffee, Broadnax took the breakfast tray up to Wythe. She then came back downstairs, finished doing the dishes as was her habit, then had some coffee herself. Almost at the same time, Brown and Broadnax started feeling sharp agonizing shooting pains in their stomachs. It was a hundred, even a thousand times worse than food poisoning. Wythe, upstairs, also started to feel incredibly excruciating pains. He dropped to his knees, went into a seizure and vomited. Somehow he made it downstairs only to see Broadnax and Brown also gripped in debilitating agony. In a panic, Broadnax made it out to the street and summoned a doctor.

“I AM MURDERED!”

When two friends rushed into Wythe’s house, they carried him back up to bed where he propped himself up in pain and mouthed, “I am murdered.”[11] The next day, Monday, May 26, Wythe, Brown and Broadnax, laying in pain brought on by the mysterious illness, were being examined by two small town local doctors. The community, however, began to talk as if this was a case of deliberate poisoning – probably by arsenic. Furthermore the town gossips almost all came up with the same culprit of the calamity – that no-good grandnephew of Chancellor Wythe – George Wythe Sweeney. As if to add ammunition to the community chatter, on Tuesday, May 27 – two days after the alleged poisoning – Sweeney was (surprise) picked up by the constable after the Bank of Richmond caught Sweeney trying to cash a seventh check signed by George Wythe, this time for $100 – a huge amount of money back then. Sweeney was arrested and charged with forgery. Incredibly, Sweeney sent word to his granduncle telling him to post the $1,000 bail but Wythe was drifting in and out of painful consciousness and it never happened. So bail was never made and Sweeney cooled his jets in the jail cell waiting for his forgery arraignment and trial.

The jailer, William Rose, checked Sweeney’s pockets before putting him into the holding cell and found a weighty rolled-up piece of paper in his pocket. Sweeney said it was a roll of pennies and Rose let him have it back. Later, a small black servant girl named Pleasant found a piece of rolled paper and what looked like yellowish-white powder in a garden on the other side of a brick wall enclosing the jail’s exercise yard. William Rose made note of it and went on with the business of running a town jail.

THE TRIO OF DOCTORS DELIBERATE

Within days of falling seriously ill, the first two doctors had been dismissed and George Wythe had at his bedside three of the young nation’s most accredited doctors. Doctors James McClurg, James McCaw, and William Foushee had all graduated from the prestigious medical school at Edinburgh University, probably the finest medical institute in the world. The doctors had also heard the Richmond rumors about arsenic poisoning and were aware of public expectation that the doctors would indeed find arsenic poisoning as the cause of the illnesses. This is why the doctors unanimously declared that the illness was cholera. Never mind that there had never been a cholera outbreak in America; small pox, yellow fever, malaria, yes, but never cholera.[12] But there’s always a first time, the doctors figured; the symptoms seemed to fit cholera and they made the assumption that the members of the Wythe household all drank contaminated water from the same polluted source. We now know that all three doctors had been specialists in epidemics, so they were looking at the medical symptoms through their own predispositions, making the illness fit their diagnosis. We also know that the ego-maniacal Dr. McClurg had positioned himself as the lead doctor of the trio and that the other two would never second guess the distinguished McClurg. Since Dr. McClurg said it was cholera, well, that’s what it was.

George Wythe didn’t buy it and told his friend and neighbor William DuVal, the mayor of Richmond, to search young Sweeney’s bedroom. DuVal found pieces of paper, arsenic and sulfur, and a white substance sprinkled on a bowl of old discolored strawberries. DuVal declared it to be arsenic and said Wythe had been poisoned by his grandnephew.

THE FUNERAL AND CSI: RICHMOND

On June 1, Michael Brown died after writhing in agony for a week. George Wythe was heartbroken. Furthermore, he figured his own death would be not too far off. Wythe called for his friend, Edmund Randolph.[13] Wythe knew Sweeney had been jailed on forgery charges and arsenic had been found in his bedroom, and that Sweeney was the only one of the household not sickened. Wythe was kind-hearted to a fault but was finally seeing his grandnephew for what he really was – someone who would murder three innocent people for an inheritance. Wythe summoned all his strength and sat up in bed. He dictated to Randolph the final codicil change to his will.[14] In it he acknowledged the death of Michael Brown. He took Sweeney completely out of the will and gave that share to Sweeney’s brothers and sisters, Charles, Jane and Ann Sweeney. He bequeathed his rare books[15] and a “small philosophical apparatus” (a globe of the earth) to his life-long friend and then-President Thomas Jefferson. On Sunday, June 8, 1806, two weeks after he was poisoned, George Wythe died. Richmond’s church bells rang all day long, 30 days of mourning was declared and Virginians wore black armbands. Nothing along those lines had occurred since the death of George Washington. Wythe’s funeral was held on Wednesday, June 11 and he was buried at St. John’s Church where legend says Patrick Henry gave his fiery “Give me liberty or give me death” speech so many decades earlier.

By now more details had come to light in the investigation of the George Wythe case. The jailer had handed over the information about arsenic being found with the paper on the other side of the jail wall from where Sweeney was being held. DuVal had testified that he found matching paper and arsenic in Sweeney’s room, and arsenic on an ax in Wythe’s outhouse and smokehouse. It had looked like the ax was used to pound the arsenic into a finer powder. Broadnax swore she saw Sweeney reading his granduncle’s will days before the illnesses had struck, and dumping something into the coffee pot minutes before they all got deathly sick. Sweeney’s friends snitched that Sweeney had asked them how to kill rats and where someone could get “rats bane.”[16] The local pharmacist testified that Sweeney came in with a written permission to buy arsenic to kill rats. With public pressure mounting now, on June 18, 1806 George Wythe Sweeney was charged with murder and it was decided that he would stand trial for that charge first. The search began for a prosecuting attorney. But who in their right mind would defend the killer of George Wythe?

“CUT ME!” – WYTHE GETS A BOTCHED AUTOPSY

Before Wythe was buried, his wishes were observed. Just before he succumbed, he hoarsely whispered repeatedly, “Cut me!”[17] Bedside friends interpreted this plea as Wythe wanting an autopsy done. Wythe’s three doctors were probably quietly thinking that perhaps an autopsy was in order. Their earlier diagnosis of cholera just wasn’t holding up too much anymore because most cholera victims died within 48 hours and the outcome was making them look bad. Brown had lingered for a week after falling ill and Wythe didn’t die for a full two weeks. Lydia Broadnax seemed to have slowly recovered, although her eyesight was severely affected and would stay very poor for the rest of her life.

The doctors had made the medical declaration that the three weren’t poisoned by arsenic partly because arsenic was known to kill very quickly. That’s why even medieval kings employed food tasters – if the tasters will still alive minutes later, the food wasn’t laced with arsenic. (It never occurred to the eighteenth century doctors that factors such as the amount of arsenic administered, the person’s metabolism, weight, or stomach contents can affect the time it takes for arsenic to kill. Those were all factors that directly influenced the Wythe household poisoning.)

With their earlier diagnosis of cholera not looking too plausible, and the claim of arsenic poisoning not valid to the three distinguished doctors, on June 8 Dr. James McClurg opened the chest cavities of both Michael Brown and George Wythe. Dr. McClurg, who also happened to be an expert on stomach bile, of all things, took one glance and officially declared that the cause of death for both Brown and Wythe was black stomach bile. The other two doctors looked on in awe at Dr. McClurg’s medical expertise. McClurg was wrong of course. The cause of death was arsenic poisoning. Even more tragic is that one of many common and well-known chemical tests could have been run on the tissues, even in 1806, which would have shown conclusively the heavy presence of arsenic.[18] In fact, for 60 years before 1806, almost anywhere in the civilized world, testing for arsenic had become almost standard practice in any autopsy of dubious death. The doctors didn’t even bother to open the stomachs of Wythe or Brown which would have unquestionably shown the damage from arsenic. A standard examination of the stomach lining sometimes even showed tiny arsenic traces on the stomach walls. In an autopsy where arsenic was suspected, the liver, kidneys and stomach should have been examined. No organ tissue examinations, no tissue testing. None of this was done. The doctors declared black stomach bile most likely the cause of the deaths. That is what the doctors officially told the Virginia governor, William H. Cabell, who in turn told the newly-named defense attorney – even though doing so was highly improper and illegal. But it would be okay because one of the two defense attorneys for George Wythe Sweeney was William Wirt – Governor Cabell’s brother-in-law. Wait, it gets better.

- Lewis Mattison, “Life of the Town” in Richmond, Capital of Virginia: Approaches to Its History (Richmond, VA: Whittet & Shepperson, 1938), 44.

- Hugh Grigsby, The History of the Virginia Federal Convention of 1788: With Some Account of the Eminent Virginians of That Era Who Were Members of the Body, vol. 1 (Richmond: Virginia Historical Society, 1855), 75.

- Bruce Chadwick, I Am Murdered – George Wythe, Thomas Jefferson, and the Killing That Shocked a New Nation (Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2009), 8-9.

- Della Gray Barthelmas, The Signers of the Declaration of Independence, A Biographical and Genealogical Reference, (Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, Inc., 1997), 303.

- The Murder of George Wythe. Two Essays: “The Murder of George Wythe,” Julian P. Boyd; “Examinations of George Wythe Swinney for Forgery and Murder: a Documentary Essay,” W. Edwin Hemphill, reprint from the William and Mary Quarterly, 1955, (second printing), 5-7.

- Denise Kiernan and Joseph D’Agnese, Signing Their Lives Away (Philadelphia, PA: Quirk Books, 2009), 193.

- Steve Sheppard, ed. The History of Legal Education in the United States: Commentaries and Primary Sources, vol 1, (Salem Press Inc., 1999), 160.

- The spelling of Sweeney varies throughout associated period documents as Sweeney, Sweny, and Swinney.

- Chadwick, I Am Murdered, 38.

- Chadwick, I Am Murdered, 14.

- The Library of Congress, The Thomas Jefferson Papers Series 1. General Correspondence. 1651-1827, William DuVal to Thomas Jefferson, June 8, 1806, image 155. http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.mss/mtj.mtjbib016181 (accessed November 15, 2013).

- The first cholera epidemic in America wouldn’t happen until 1832. http://ocp.hul.harvard.edu/contagion/cholera.html (accessed November 17, 2013).

- Chadwick, I Am Murdered, 104.

- Library of Congress, The Thomas Jefferson Papers Series 1. General Correspondence. 1651-1827 George Wythe, June 11, 1806, Last Will and Testament with Codicil, Images 314-319, http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.mss/mtj.mtjbib016255 (accessed November 11, 2013).

- Wythe obviously didn’t know some of his prized books had already been stolen and sold by Sweeney. However a catalogued amount of Wythe’s remaining books were transported to Jefferson’s Monticello following Wythe’s death. These books became part of the collection Jefferson would end up selling to Congress to replace the books destroyed by the British in the War of 1812 when the Library of Congress was burned.

- “Rats bane” was a colonial-era name for arsenic. Mary Miley Theobald, “Murder by Namesake: The Poisoning of the Eminent George Wythe”, Colonial Williamsburg Journal, (Winter 2013), http://www.history.org/Foundation/journal/winter13/murder.cfm (accessed November 8, 2013).

- Theobald, “Murder by Namesake.”

- Arsenic (arsenic trioxide) had been the poison of choice since the days of the Greeks because of ease of use and being almost non-detectable. By the time of Wythe’s death, a very standard test for arsenic had already been developed and was described in medical journals, text books, articles, and classroom-lab demonstrations of the time. There is no way Wythe’s doctors were unaware of this standard test. The test involved submerging flesh from the deceased person into a solution, “and then to bubble hydrogen sulfide gas through the solution.” If a left-over yellow sediment was present, then arsenic was in the flesh. “This test had been used for years, yet the doctors not only neglected to perform it, but did not take any biopsies of Wythe’s organ tissue.” Three other common chemical tests for arsenic presence, none of which were performed on Wythe, are also described on these pages. Chadwick, I Am Murdered, 201-202.

One thought on “Murder of a Declaration Signer (Part 1)”

This is fascinating! I feel I know a lot about history, but have never heard this before.