When the Continental Congress first commissioned the use of private ships and boats of war in April 1776, they specified that each vessel’s commander had to deliver a bond payable to the president of the Congress before the privateering commission — called a letter of marque and reprisal — could be granted. These bonds were in the amounts of $5,000 for vessels of 100 tons or under and $10,000 for larger ships (later, some bonds were increased to $20,000).[1]

Privateers weren’t members of the army or navy. Instead, privateers — owners, officers, and crew alike — were private citizens and therefore not subject to any kind of military code. The object of these bonds was to keep privateers on a tight leash. There were strict rules privateers had to follow, like not torturing or stealing from prisoners, and privateers had to bring captured vessels, called prizes, back to port where they were libeled — the contemporary term for submitting the vessels and their cargoes to the admiralty court, which would determine if they were lawful seizures from the enemy. If so, the prizes were liquidated and the proceeds split among the privateer’s owners and crew. More importantly, privateers were only allowed to target the British and their allies, which included enemy privateers. Failing to follow the rules of their commissions risked forfeiture of the bond and revocation of legal protection, making the captain and ship owners or investors vulnerable to criminal and civil charges. In other words: the bonds were meant to keep the privateers from becoming full-blown pirates.

Some states issued their own privateering commissions as well. In Connecticut, there was also another level of privateers who sailed in small craft. Officially they were known as “armed boats.” To their victims, they were the dreaded “Whale-Boat men.”[2]

A whaleboat (not to be confused with a whaler) was an open rowboat, generally about 30 feet long, “sharp at each end and manned with 8 to 10 oars.”[3] Some had removable masts for longer voyages and each was crewed by about seven to ten men.[4] Armament consisted of whatever swords, clubs, or firearms the sailors brought with them, although one source mentions a three-on-three engagement in Long Island Sound in which the Patriot whaleboats had a swivel (firing half-pound shot) while the Loyalists “had a small piece.”[5]

Whaleboat raiding by both Patriots and Loyalists across Long Island Sound began early in the war and continued at least into 1782. Thirteen whaleboats had been commissioned by Connecticut “to cruize in the Sound” by July 1780, each operating under a bond of £2,000.[6] Their main intent was to prevent unauthorized commerce and traffic between Connecticut and Long Island; in some cases, goods were allowed to be brought into Connecticut but it was illegal to trade or sell anything outside the state without permission. A more aggressive goal was “to land on Long Island and there take all British property.”[7] Yet just like the bigger privateers, upon their return the whaleboat crews were expected to libel anything they captured.

That was the theory, anyway.

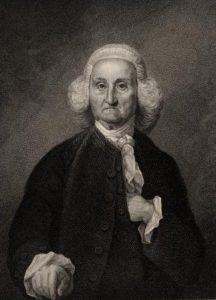

“Whereas sundry and repeated complaints have been made that persons under authority of commissions given to armed boats to go on shore on Long Island to act against the enemy there,” wrote Connecticut governor Jonathan Trumbull to Captains Jonathan Vail and Jeremiah Rogers in August 1781, “have unjustly and cruelly plundered many of the friendly inhabitants there, brought off their effects, and have not caused them to be libelled and condemned in course of law — You and each of you are hereby required … to account for your conduct in that respect.”[8] These two weren’t the only whaleboat commanders Trumbull marched to the woodshed. He wrote to other captains as well, including Jesse Leavenworth, Peter Hallack, and Jonathan Solomons. Peter Griffin, who had been granted his commission a year before “for the purpose of guarding the sea coast of this State and of the sound and islands of said coast,” was recalled after “repeated complaints of your doings in making unlawful and improper depredations on the inhabitants of Long Island, and not libelling and bringing to tryal many of the effects you have taken.”[9]

After the British victory in New York City when much of Long Island became a Loyalist stronghold, many Patriots fled north to Connecticut. Since trade and travel across Long Island Sound was strictly regulated, refugees often petitioned Trumbull and his Council of Safety for permission to return to Long Island to collect belongings and livestock. Even when permission was granted, no sooner had the refugees’ keels struck the sand than the whaleboat men descended. In February 1778, a group of Long Island refugees testified to the Connecticut Assembly that upon arrival in Saybrook, Connecticutt, after a sanctioned voyage to Long Island, an officer from the Continental frigate Trumbull, a whaleboat commander “and others their associates, came and seized the memorialists’ said effects and forceably took the same out of their hands and refuse to deliver or do what is just.”[10] Though the attack occurred on land, the fact that the thieves’ leaders were officers suggests they believed their actions were justified by the authority of their commissions. There were so many similar complaints that the Assembly appointed a committee to sort them out.

Of course, these were only the assaults committed by commissioned whaleboats. The real problem was that anybody who had a whaleboat and some roughneck buddies down at the tavern could go Viking.

“[T]wo boates crossed on the fourteenth instant,” wrote Caleb Brewster to New York governor George Clinton in the summer of 1781. “[They] went up about twelve at night to the houses of Capt. Ebenezer Miller and Andrew Miller, demanded entrance which was granted, as soon as the door was opened they demanded his arms which he gave up; his son hearing a noise below stairs got up out of bed shoved up the chamber windo. One of the party without ever speaking to him, shot him dead in the windo …”[11]

Brewster listed further atrocities: houses broken into and plundered, the inhabitants beaten or hung up and tortured until they confessed where their money was hidden and then their throats cut. Brewster knew Long Island and its people well — many of them had been neighbors. Born and raised in Setauket, Long Island, he too was a Patriot refugee who often returned across the Sound in whaleboat expeditions or while working as part of the Culper spy ring.[12] “Theres not a night but they are over,” Brewster concluded, “if boates can cross peopple cant ride the roades but what they are robbed.”[13]

Clinton complained to Trumbull “that several of the Inhabitants of Suffolk County whose attachment to the Cause of America is indisputable, have been divested of their Property by Parties acting under Commission from your State,” although Brewster’s later comment that the whaleboats crossed at night suggests not every vessel had its paperwork in order.[14] Trumbull brushed aside Clinton’s grievances. He responded, “The Commissions lately granted by this State … have been carefully guarded by Instructions given the comanders of the Boats, calculated to prevent the Practices you mention, accompanied by Bonds.” After all, Trumbull said, if the victims’ claims were legitimate, then “on proper Proofs, Prosecutions will be made & full Justice may be obtained in due course of Law on the Bonds.” He did add: “I fear, however, that in some Instances this good Intention has by evil men ben contravened.”[15]

Trumbull didn’t want to admit what he already realized: the whaleboats were virtually flying skulls-and-crossbones. In January 1781, just a few months before this exchange, Trumbull had revoked all of the commissions “On consideration of the many evils committed by the armed boats.”[16]

Yet the raids continued by both sides. While Loyalist whaleboat raids were just as common in earlier years — the burning of Fairfield, Connecticut in 1779 was preceded days earlier by such an assault — the journal entries of William Wheeler, a farmer and schoolteacher living alongside the wharves of Fairfield’s Black Rock Harbor, record a crescendo of attacks in 1781. On February 18, “A Boat came to Mill River & took 2 of the Inhabitants Prisoners” before being discovered and thwarted. On March 4, a party of 30 men in four boats burned a pair of tide mills on the river; then nearly three weeks later, another boat arrived to rob houses and take prisoners. The tide flowed both ways. On June 27 Wheeler wrote, “Near this time a great number of Whale Boats go to Long Island to plunder,” though he added 15 days later, “They returned, having effected nothing.”[17]

Trumbull again ordered the commissions “so far as they relate to their landing or going upon Long Island” were “revoked and made null and void” in September.[18] Still the raids continued. Finally, in November, he fully revoked the commissions a second time, commanding that “the several persons holding the same are strictly forbid to act anything under the same,” and instructing selectmen to communicate this order to the commission holders so “that none of them may plead ignorance thereof.”[19] Trumbull also ordered the military to seize all boats and small craft along the entire shoreline — ostensibly to prevent illicit commerce, but likely with an aim toward stopping the raids.[20] He must have known not all of the raiders operated under commissions issued by the state.

After this, complaints about the Connecticut boats vanish from the public records but raids by both groups persisted into the following year, even if they became less frequent in the aftermath of Yorktown. In June, Wheeler mentions a boat crewed by 10 sunk off Black Rock, and December 1782 saw the famous “Boat Fight” of Long Island Sound, in which Caleb Brewster and friends engaged a like number of Loyalist whaleboats and — after brutal hand-to-hand combat — emerged victorious: “[T]here was a large Irishman in the enemy’s boat, who walked several times fore and aft, brandishing his broadsword till Hasselton, a mighty fellow from the State of Massachusetts, snatched it from him & cut his throat from ear to ear; he died immediately.”[21]

I guess the takeaway here is: Live by the whaleboat, die in the whaleboat.

[1] Continental Congress, 3 April 1776, vol. IV of Journals of the Continental Congress, 1774-1789 (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1906), 251-254.

[2] Frederic Gregory Mather, The Refugees of 1776 From Long Island to Connecticut (Albany, NY: J.B. Lyon Company, 1913), 203.

[3] William Wheeler, The Journal of William Wheeler, reprinted in Cornelia Penfield Lathrop, Black Rock, Seaport of Old Fairfield, Connecticut, 1644-1870 (New Haven, CT: Tuttle, Morehouse & Taylor Co., 1930), 34.

[4] The instructions to “Benjamin Conklin and Daniel Foredom, commanders of armed boats,” specified “said boats [to carry] seven persons each.” The Governor and Council of Safety, 28 June 1780, vol. III of The Public Records of the State of Connecticut (Hartford, CT: Case, Lockwood & Brainard Co., 1922), 116. William Wheeler mentions different complements: “their party consisted of 30 in 4 boats,” “Capt. Parks with 10 Guns & 21 men fird at a boat with 10 men,” etc. Wheeler, Journal, 36-37.

[6] Number of whaleboats: The Governor and Council of Safety, 30 June 1780, vol. III of Public Records, 119. Amount of bonds: Jonathan Trumbull to George Clinton, 27 April 1781, vol. 6 of Public Papers of George Clinton (Albany, NY: J.B. Lyon Company, 1902), 803. NB: while the Congress and their commissions specified Continental dollars, Connecticut used the more reliable currency of pounds sterling.

[8] Jonathan Trumbull to Capt. Jonathan Vail, Trumbull to Capt. Jeremiah Rogers, 11 August 1778, vol. II of The Public Records of the State of Connecticut (Hartford, CT: Case, Lockwood & Brainard Co., 1895), 110.

[9] Letters to commanders of armed boats: Jonathan Trumbull to Capt. Jesse Leavenworth, Trumbull to Peter Griffin, 4 August 1778, vol. II of Public Records, 107; Jonathan Trumbull to Capt. Jonathan Vail, Trumbull to Capt. Jeremiah Rogers, 11 August 1778, vol. II of Public Records, 110. Peter Griffin’s commission: the Governor and Council of Safety, 2 September 1777, vol. I of The Public Records of the State of Connecticut (Hartford, CT: Case, Lockwood & Brainard Co., 1894), 391.

[11] Caleb Brewster to George Clinton, 20 August 1781, vol. 7 of Public Papers of George Clinton (Albany, NY: Oliver A. Quayle, 1904), 233-234.

[12] Biographical information on Brewster: Frederic Gregory Mather, The Refugees of 1776 From Long Island to Connecticut, 278-279.

[13] Caleb Brewster to George Clinton, 20 August 1781, vol. 7 of Public Papers of George Clinton, 233-234.

[14] George Clinton to Jonathan Trumbull, 16 April 1781, vol. 6 of Public Papers of George Clinton, 778-779.

2 Comments

I grew up on Long Island Sound and in all weather save heavy mist or fog, Connecticut and Long Island are very visible to each other. The farther east, the greater the distance between the two land masses. My questions are (I) that with the amount of whale-boating apparently going on, how close to NY and the western tip of Long Island did the rebels operate? and (II) didn’t the British regularly patrol LI Sound, in which case how dangerous was the enterprise? Very interesting article. Thank you.

From my research the British Navy kept a very regular schedule across the Long Island Sound. Both sides did use the whaleboats and especially when there was fog the patriots took advantage of that to move information gathered by the Caleb spy ring up to Connecticut then to General Washington, and raids by Major Tallmage and his troops. Volunteers like myself have been building a replica of that type of whale boat at the Bayles Boatworks in Port Jefferson NY. The launch will be taking place May 2026.