The outcome of a war depends on far more than individual battles, but the battles are compelling to study; everyone has a favorite. The impacts of each one are numerous, and we can pontificate endless “what if” scenarios regarding the outcomes. There were, nonetheless, several battles that changed the momentum of the American Revolution – battles that stopped campaigns and caused changes in strategy. Although the outcome of every battle influenced subsequent events, only a few completely changed the momentum of a campaign or of the war itself. For a top ten list of game-changing battles, I first limited the scope to land battles fought on the North American continent. Then I considered whether the outcome of that battle changed the momentum of what was going on at the time. For example, the Battle of Brandywine was a momentous fight, but if the battle hadn’t occurred at all the overall result of the Philadelphia campaign would probably have been more or less the same; and, because the British won, they sustained momentum that they already had. An American victory at Brandywine would’ve been a game-changer – but that didn’t happen. In some cases it’s difficult to isolate battles from campaigns – Yorktown being a fine example – so I’ve mingled the two a bit. Here’s my list: some famous, some not so famous, but each one an event that shifted momentum from one side to the other and shaped the overall conduct of the war. Which battles would make your list?

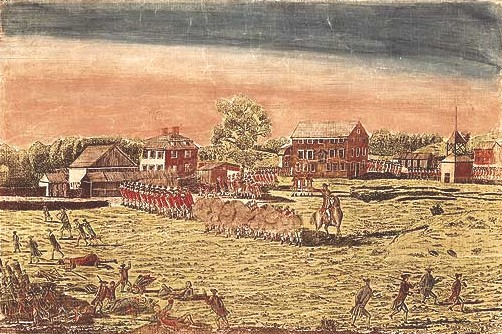

1. Lexington and Concord, April 1775

Although more a series of skirmishes than a pitched battle, this clash of arms was the result of tensions that had built over a long period and changed the conflict from politics and social unrest to open warfare. “Ever since the 19th, we have been kept in constant alarm; all Officers order’d to lay at their barracks.”[1]

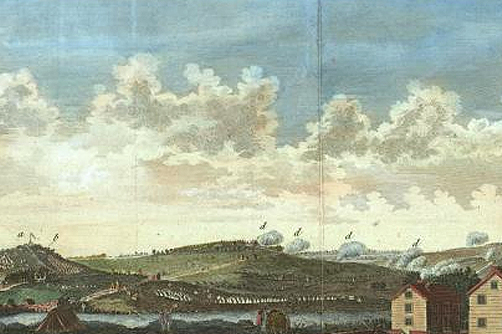

2. Bunker Hill, June 1775

This costly British victory helped shape the early course of the war by proving that intimidating force alone would not bring about victory. It also proved that there was no going back: the war would be a long one with no immediate diplomatic solution. “I believe the regulars will hardly venture out, for they must lose a vast many men if they should, and they cannot afford to purchase every inch of ground as they did at Charlestown.”[2]

3. Quebec, December 1775

A series of American victories along the waterways from Lake Champlain into Canada ended at Quebec. Had Americans seized the city, the entire northern theater of the war would have been different. “A heterogeneal concatenation of the most peculiar and unparalleled rebuffs and sufferings that are perhaps to be found in the annals of any nation…”[3]

4. Charleston, June 1776

Often disregarded as a minor action, the British failure to take this major seaport forced the war’s focus to be primarily in the north for the next several years. “Nothing, therefore, was now left for us to do but to lament that the blood of brave and gallant men had been so fruitlessly spilt.”[4]

5. Trenton, December 1776

The British army’s dramatic success in New York and New Jersey in 1776 was, arguably, predictable given its overwhelming size and skill. The sudden defeat at Trenton and the ten days of chaos that followed was not expected, and preserved American military will. “It is now announced in our general orders, to our inexpressible joy and satisfaction, that the scene is in some degree changed, the fortune of war is reversed, and Providence has been pleased to crown the efforts of our commander-in-chief with a splendid victory.”[5]

6. Saratoga, October 1777

It wasn’t so much any single battle but the failure of the British campaign from the north that made this the war’s most significant military turning point. The surrender of a British army encouraged France to openly join the conflict. “Thus ended all our hopes of victory, honour, glory &c &c &c”[6]

7. Rhode Island, August 1778

This failed American campaign, often overlooked as insignificant, not only stopped American military momentum gained from Saratoga and the recovery of Philadelphia, it showed that alliance with France would not bring a speedy end to the war. The northern theater remained in a stalemate for the rest of the war. “There never was a greater spirit seen in America for the expedition, and greater disappointment when Mr. Frenchman left us.”[7]

8. Kings Mountain, October 1780

The annihilation of loyalist militia on the South Carolina frontier forced the British to revise their southern strategy and demonstrated that their overextended forces could be defeated in detail. “The destruction of Ferguson and his corps marked the period and the extent of the first expedition into North Carolina… the total ruin of his militia presented a gloomy prospect at the commencement of the campaign.”[8]

9. Cowpens, January 1781

This sudden defeat of a substantial British force stopped British offensive momentum in the south and renewed the spirits of American forces, initiating the campaign that brought the war to an end. “I was desirous to have a stroke at Tarleton… & I have given him a devil of a whipping.”[9]

10. Yorktown, October 1781

Not a pitched battle but a protracted siege that ended in the surrender of a substantial British army, this operation was the zenith of French-American cooperation and the end of major British military operations in America. “The annals of history do not exhibit a more important period than the present.”[10]

49 Comments

I’d like to know your reason for omitting the Battle of Long Island/Brooklyn. After the successful Siege of Boston Washington saw ‘NYC’ as the next major conflict. Of course, he was correct, lost the battle and had to retreat, retreat and retreat. But for that loss and the eventual trek through NJ into PA, there would have been no Trenton. If ‘turning point’ is the thesis you need Long Island’s loss stuck in between Boston and Trenton.

I’d also put my vote behind NYC’s addition to the list; however, I’d be inclined to include it more for the Continental Army’s lessons learned than for serving as a prelude to Trenton.

Per my longer comment below, I view the British campaign as having opened when they arrived in New York harbor with overwhelming force. While battles like Brooklyn and others were necessary for them to achieve victory, they had the initiative from the moment they arrived in the area and no battle took it away from them. This doesn’t mean the battle wasn’t important, only that it didn’t change initiative from one side to the other.

I would add the Battle of Fort Mercer. Although a footnote to the Philadelphia Campaign, the American victory over a superior Hessian force in defense of the fort stemmed the tide of American defeats at Brandywine, Paoli, and Germantown. The overwhelming victory garnished public confidence which was deteriorating throughout the region after the fall of Philadelphia and provided an additional morale boost to an American army embarking on a winter at Valley Forge.

No Brooklyn? No Brandywine? WIth this list, one wouldn’t know that the royal forces entered a nominally independent nation and quickly took over its second-largest city, then a year later took over its capital. That’s gotta hurt.

What about the British military’s successful siege of Charleston? That seems like a bigger turning-point than the first, unsuccessful siege in 1776. What about Camden?

Philosophically, this list seems to be based on the idea that British military success was a given so British military victories were less often “turning-points” than American ones. But between every two shifts of momentum to the Continentals, there had to be a shift back to the British, right?

I think Brooklyn, Brandywine, Charleston, Camden and Guilford Courthouse were all tied for No. 11.

But the battle of charlestown is in the list as number 4.

i mean charleston

Hi Tashin. We were discussing two different Charleston engagements. The Charleston listed at No. 4 is more commonly known as the Battle of Sullivan’s Island, June 28, 1776. The Charleston that J. L. Bell and I were referencing as another contender for this list is the 1780 Siege of Charleston. Sorry for the confusion.

The point about momentum shifts is well taken, but the British, in general, obtained momentum by initiating campaigns rather than by winning individual battles. We could argue, for example, that the Philadelphia campaign would’ve had the same outcome if the battle of Brandywine had never happened. This line of reasoning is also what puts Rhode Island on the list; in that case, an American victory was almost a given, but did not occur. In general, the battles on this list are the ones where the outcome was startling and unexpected given the forces involved and the side that was already on the offensive.

This is exciting news because my great-great-great-great grandfather Captain Clement Gosselin of the 2nd Canadian Regiment was involved in 2 out of the 10 – Quebec and Yorktown! 20% – not bad for a French-Canadian!

Curious as to why Guildford Courthouse isn’t mentioned (though I see that it was in an 11th place tie). It was pivotal to success at Yorktown and one of the bloodiest battles fought… even if the outcome is often debated. It seems to regularly be overlooked by historians…

These battles (or in a few cases, non-battles) were chosen because they CHANGED the course of a campaign that was already in progress – the side that had the initiative lost it because of the outcome. Battles aren’t on this list is because they didn’t CHANGE the momentum of the campaign that they were part of.

Brooklyn (Long Island), for example, had an (arguably) predictable outcome. Momentum favored the British from the time they arrived in New York harbor with overwhelming force. Individual battles, including Long Island, were necessary to effect that goal, but given the forces involved the outcome of the campaign was reasonably predictable: the British achieved all of their geographic objectives, all the way to the Delaware River.

The same can be said for Brandywine – the British initiated a campaign to take Philadelphia, and the campaign was successful regardless of the individual battles that occurred on the way. And the same again for the 1780 siege of Charleston – the British took the initiative by deciding to take the city, and were completely successful.

Camden and Guilford Courthouse are tougher to classify in this way. It’s hard to say who had the initiative at Camden; an American victory may have been a game changer, but the American loss simply allowed the British to continue with a plan they’d already set in motion. Guilford Courthouse (arguably) took the offensive capability out of Cornwallis’s army, but the extent to which it singularly caused the move to Yorktown is debatable.

Many other battles were important in many ways, but these ten (in my view) swung the initiative from one side to the other, rather than allowing one side to retain initiative.

When you listed Charleston, I thought you’d mean 1780 not 1776.

I put Monmouth Court House on the list as Clinton didn’t do much out of NYC after that. Replacing Rhode Island which was pretty much a side-show.

What? No “Battle of Moore’s Creek Bridge”? That Patriot-Scottish/Loyalist skirmish made the British abandon the southern colonies until 1780. Then, forgetting what they’d learned, again thought that Loyalist support was stronger down there than it really was.

Nothing said about expelling the British from Baton Rouge, Mobile, Pensacola and securing the Mississippi River Valley?

Excellent way to start a good discussion of the subject. Your list is nicely reasoned, should make readers think deeply on the matter, and was destined to encourage rebuttal. Kudos.

I would have said Guilford instead of Cowpens. Cowpens was a wonderful victory and, like all victories, gave the Patriots a nice morale lift. However, Cornwallis didn’t really lose the initiative until after Guilford. Up to that point, the CA was on the run. Even at Cowpens, the real question after the battle was whether Morgan could get away without losing the prisoners (and perhaps his own). It was more like a biting Cornwallis in the ass while Guilford CH actually changed the initiative and sent Cornwallis to the safety of Wilmington to regroup and come up with plan B.

Very well detailed observations, Wayne. I realize that you wrote this a while ago, so I’m not sure if your opinion has changed, but there a couple reasons I’d keep Cowpens on the list. The first being that after the loss, Cornwallis, who never listened to anyone, was obsessed with getting payback. He foolishly chased Greene. If Morgan was defeated at Cowpens, it’s unlikely the chain of events leading to Yorktown would have ever happened.

The second reason is the return of the much needed Morgan to the Continental Army, who in my opinion is one of the top five continental officers responsible for winning the war. After resigning due to non-promotion and total disrespect by Congress, (Imagine Congress commissioned Wilkinson to Brigadier General based on Gates ridiculous recommendation even though Wilkinson had done nothing) he came back and did what he always did, and more; used the terrain to his advantage, (Similar to Saratoga) aggressive battlefield tactics, (Like Quebec, Saratoga) developed an exception battle plan, (If original or not can certainly be debated) and ended up winning a much needed battle for the Continental Army.

Jeff, truth is I would like to find room for both Cowpens and Guilford in a top ten list. But, of course if it were up to me, the southern battles would always show up first. 🙂

I am delighted that you mentioned ‘if original or not’ about Morgan’s battle plan. Not to speak badly of Morgan in any way (I am also a huge fan of his) but, just to give a bit of nod to Thomas Sumter and maybe give credit where due, I will add some info from a recent research trip in the pension files. In the application of James Clinton S2437 as transcribed by Will Graves and located at http://revwarapps.org/s2437.pdf , he talks about Sumter’s plan and its results.

“General Sumter rode along our lines and asked if any would volunteer to bring on the attack, by making one attack and retreating back so as to draw the enemy to a different point.” Apparently Clinton volunteered and, “this succeeded as was expected” and Tarleton’s legion was drawn into a disastrous charge. “They immediately retreated” with a loss of about 20 dragoons “on the spot”

To me, this is very similar to Cowpens and represented Sumter’s best battle. But of course, being a fan of the SC partisans, I tend to favor Sumter more than many folk do. 🙂

That’s a really great find, Wayne. Graves’s pension application provides more specifics of the internal workings in his militia company, than those of most pension applications. Granted 50 years have passed since the events described, so some forgotten information may have been gathered to fill in the gaps, but that seemed to be a common practice, and Graves does give many specifics that only he would know.

Those militia in North Carolina were underrated. They did a heck of a lot of damage to Cornwallis and Carleton, not just in the numerous battles around the state but by more importantly blocking supply lines.

There’s no doubt that there are similarities in strategy between Blackstock and Cowpens. It may have come more out of desperation in Sumter’s case, having to retreat before taking a defensive stand, but the actual strategy involved with the frontal attack by Tarleton, Sumter’s second line firing from behind first, and right flanking the attackers, are all similar and precede that of Cowpens. Maybe because it was with Militia and on a smaller scale it doesn’t get nearly as much attention as it should, but that’s a solid source to back up the argument.

Cowpens destroyed the aura of invincibility around Tarleton, but it did not fatally damage Cornwallis’ army, it was Guilford Courthouse that did it.

Mark, the aura of invincibility around Tarleton had already been taken care of 2 months earlier at Blackstock’s Plantation. Probably Sumter’s best battle. He later believed that Morgan actually got his ideas for Cowpens from Sumter’s setup at Blackstock’s where ‘poor Money’ was killed trying to lead an assault against Elijah Clark and the Georgians.

Good point Tarleton was beaten at Blackstock, but putting it into the context of the time, he was still expected to win at Cowpens, the fact that he lost was an upset. On being told the outcome Cornwallis supposedly leaned on his sword until it snapped, although that might be anger at Tarleton’s immaturity!

Yes good point

The Siege of Savannah in 1779 probably would have been fatal for the British had they lost it, they probably wouldn’t have been able to carry out the southern campaign the year later. When he heard the news of the battle, Henry Clinton wrote; “I think that this is the greatest event that has happened the whole war”.

I have to say that Clark’s Western Campaign which solidified American claims to the Old Northwest was a critical point in the war. Had Kaskaskia not been taken (no battle) or Vincennes not have been captured by Clark, Canada would reach much farther south today. The Ohio River would be the northern boundary of the midwest.

I would echo John Rees comments.

I happy to see Saratoga and agree with Bunker Hill and Lexington.

I think the Americans had little chance of winning and holding on to Quebec – but who would have ever thought they would do so well in that battle and yet lose.

A very good list.

Gave you a credit on

What’s New on the Online Library of the American Revolution.

Based on the criteria involved, this is an excellent list, Don. One observation I have why limit the criteria to only land battles in the North American Continent? I say this because this eliminates the only major naval battle in the North American Continent, the Battle of Valcour Island.

Many would argue that the Battle of Valcour was a critical engagement for the Continental Army in not only buying time for the following year’s campaign, but in showing that the Americans could put up a fierce and tenacious fight, something the British did not expect. More so than anything, Carleton’s caution in preparing for the battle, lead to the delay. When Arnold took his fleet up to Windmill Point, which Carleton described as “a considerable naval force”, this had an obvious effect on Carleton. At that point the Carleton felt the need for to have in his flotilla the unnecessary “Inflexible” which took an extra four weeks to transport and reassemble.

That being said, had the British fleet gone straight down to Ticonderoga, either unopposed, or encountered the Continental fleet in open water, (Where the British would have likely destroyed the entire fleet in a matter of a couple hours) things would have likely turned out differently.

These are thoughtful questions, Jeff.

I limited the criteria primarily because I wanted some kind of boundaries to limit the discussion from extending to the global aspects of the war. Events like the Siege of Gibraltar and the defense of the English Channel had major military significance; I confined the list to North American land battles to keep it simple.

That said, I do consider the battle of Valcour Island to be within the scope of consideration, for even though it occurred on the water it was part of a land campaign. But I’m one of those dissenters who doesn’t think the battle was a major factor in the campaign. I do understand and respect the arguments of those who do think it was pivotal, but my own belief is that Carleton would have retreated for the winter even he had succeeded in reaching Ticonderoga in 1776, because he’d have gotten there too late in the season to establish the necessary lines of communication with Quebec. I could be wrong, of course; we’ll never know what would’ve happened if Arnold hadn’t given battle that day. I think, though, that the real delay was caused by Carleton having to build a fleet in order to proceed down the lake, rather than the battle that occurred in October, that prevented British success that year. In that sense it was a successful campaign for Arnold, but not (in my view) because of the battle of Valcour Island.

Don, thanks for providing such detailed rational behind the exclusion of this particular battle. I see your point, it can be argued both ways, and there’s no right or wrong conclusion. Like you said, “we’ll never know what would’ve happened if Arnold hadn’t given battle that day”. There are a lot of what ifs, and it’s impossible to delve into the psyche of the two main opponents at that particular time, each complicated individuals, especially under those circumstances.

I suppose that the reason I would include the battle, which you alluded to, is more so the tactics leading up to the actual battle that cost the British the delay. Would another American Commodore have taken his flotilla so close to St Jean to “intimidate” the British? Maybe, though Arnold was well aware of Carleton’s cautious nature and that this action would likely have a greater psychological impact on an opponent like Carleton. Would another American Commodore publicly announced to his men that they would be attacking St Jean, knowing that word of those comments would reach Carleton, even though Arnold had no intention of attacking St Jean? Probably not. And finally would Carleton have had the respect for any other Commodore of the American fleet had it not been Arnold, who he was obviously familiar with from Quebec and thought of as a relentless rebel? Again, doubtful.

With those questions in mind, I don’t believe Carlton would have waited for the construction of the “Inflexible” had Arnold not been the Commodore of the American fleet. That’s just an opinion, and though what I put out there was not part of the battle, they are the tactics and the possible mindset leading up to it.

What about the Siege of Savannah in 1779? One of the bloodiest of the war and a major British victory.

Since this popped back up in the most recent comments on the front page, thought I’d add my thoughts. You won’t get any hostile disbelief from me for what was or wasn’t chosen though, I promise! Despite my opinions, everyone here has certainly given convincing reasons for the battles they’re arguing for 🙂

First, I would suggest King’s Mountain is in many ways overrated. If anything its importance was in demonstrating the value of constantly disparaged militia (and even more ad-hoc forces than that) when used appropriately. But Cornwallis’s position in NC was already extremely precarious (indeed moving into NC so early was ill-advised), and the defeat at King’s Mountain was hardly the only reason Cornwallis had to turn back to SC. But more importantly, the claim that it was the turning point in the southern strategy after which the British could not find the Loyalist support it needed, is overblown. The British were beginning to notice real problems with raising Loyalist support by July 1780. The high-water mark for Loyalist turnout was actually in late May and June, immediately after the fall of Charleston. This was not, however, because Loyalist strength in the South had been exaggerated. It’s because the British did not understand what it would take to turn out the Loyalists. Throughout 1779 and 1780 they believed simply showing up was all that would be necessary – the Loyalists from the entire province would rise up and march over potentially vast distances to meet the British, and run the very real risk of being intercepted by the Patriots before they ever reached the British.

This was the greatest contribution by the Patriots – breaking up Loyalist forces (the key to the southern strategy) before they could assist the British, while the British usually focused their attention on finding the Patriot army and defeating it when they were supposed to be raising Loyalist support. This was the case during Archibald Campbell’s march to Augusta, Augustine Prevost’s march to Charleston, and then with Cornwallis through the entirety of the southern campaign in 1780-81. (And of course each one expressed great surprise that no Loyalists showed up as promised) This was the real lesson of Moore’s Creek Bridge and why that battle was important for the lessons the British failed to learn (despite Josiah Martin pointing out that the British could not rely on the Loyalists to come meet them, and would instead need to send their own forces throughout the country assembling Loyalists). So based on their mistaken assumptions of what would be needed to raise Loyalist support, the British were already questioning the value of Loyalists – particularly Cornwallis who, if we are to believe Sir William Howe in his letter to Germain in January 1778, never had much faith in the first place in strategy that depended so much on Loyalists.

(One way in which you could make the case for King’s Mountain is in the loss of Ferguson. He was perhaps too impetuous and careless of a commander, but he did have a particular talent for understanding what it took to raise Loyalist forces. Historians, however, have largely echoed Cornwallis’s criticisms of Ferguson, and naturally Cornwallis would not have paid much attention to this particular strength of Ferguson’s)

Likewise, Guilford Courthouse is, I think, also somewhat overrated. The usual argument was that it was this battle that convinced Cornwallis that he could not rely on the Loyalists, and that the key to pacifying the southern colonies was to take Virginia. But again, he had largely reached this decision before Guilford Courthouse. It was clear he had already lost all faith in the value of the Loyalists, and that he likewise believed the only thing sustaining the Patriots in the southern colonies were supplies from Virginia (a questionable assumption somewhat akin to claiming the key to pacifying South Vietnam was to bomb the daylights out of North Vietnam). Cornwallis was therefore already beginning to shift his strategic thinking before Guilford from the southern strategy that depended on support from Loyalists to one of conquest of territory, something he was much more comfortable with, and interdiction of supplies. Guilford did require that he go first to Wilmington to rest, resupply and refit, but it was of less importance than generally assumed in convincing him to abandon the southern strategy and move to Virginia (the fact that Phillips had arrived in VA and Arnold was already there just helped him decide on the timing).

On a related note, I think the reason that major British victories in the southern colonies (Savannah 1778, Briar Creek, Charleston 1780, Camden, etc) would generally not be in my top 10 of the whole war is because they really weren’t the strategic ends that were going to bring British success in the southern strategy. That strategy was based on organizing local support among the Loyalists, not just territorial conquest or even defeating the enemy’s main army. Taking Savannah and Charleston were necessary because it provided the British with a base of operations to then implement their strategy, but they were by no means sufficient for yielding British strategic success in the South. Camden, meanwhile, brought about the defeat of the Continental Army in the South, but this assumes that army had played a terribly significant role in the success of Patriot military operations in the South to that point. They really hadn’t, because the Patriot strategy was not to defeat the main British army in the field. It was to prevent the British from leveraging Loyalist support, so that the British would not be able to venture far from Savannah, Charleston, or their handful of posts in the SC backcountry without overextending themselves due to that lack of expected Loyalist support. The success or failure of British forces in the major conventional battles in the South therefore really had less impact on British strategic success than most assume. The outcome of these battles inevitably had some effect of loyalty, but much more important was the regular activity of Patriot militia (and occasionally the Continental Army) in controlling the day to day actions of the population, particularly known Loyalists. Read the letter from James Mark Prevost to Germain in the aftermath of Briar Creek in March 1779 where he expresses a great deal of surprise that such a convincing battlefield win yielded very little in terms of boosting Loyalist turnout or diminishing growing Patriot numbers.

The major conventional battle I would rate as most important for the southern campaign, in addition to Moore’s Creek Bridge and probably Charleston 1776, was Cowpens. As someone noted, it largely destroyed the mythological status of Tarleton as the bogeyman – as he had been the most effective British tool for breaking up groups of Patriot forces before they could do the same to Loyalists. Furthermore, when Cornwallis began chasing after Greene’s army, he largely gave up trying to raise Loyalist forces. He would make one last-ditch, skeptical effort in the Hillsborough area after Greene escaped across the Dan, but Cowpens had cost the British many of their mounted troops – which they would have needed to patrol the area and bring Loyalist forces safely to the army. Naturally though, Cornwallis again blamed the lack of turnout on the perfidy of the Loyalists – something historians would echo for centuries to come.

Anyway, there’s my 0.02

Great and well-reason thoughts, Dan – more than 2 cents’ worth, I’d say 🙂

I will admit that, of the ten actions on this list, I was least comfortable with Kings Mountain. But I’m also don’t know nearly as much about the war in the south, particularly the rationale behind the flow of it, as with the war in the north. I appreciate your careful explanations.

Dan, I enjoyed your post last night and found that it provided a much needed distraction from the tedium of day to day work. Worth far more than 2 cents, I might even suggest a full two bits, or perhaps a couple of continentals. There are several assertions presented that I would like to discuss further but, perhaps for the sake of brevity, I should limit to a few thoughts on King’s Mountain.

The notion that militia were used properly at King’s Mountain which served as a lesson for the use of future operations deserves a closer examination. First, the tactics used by Shelby, Campbell, & the other militia leaders was almost non-existent. They simply rode up and surrounded an equal force on top of the mountain and began assaulting up the slopes on all sides. A well trained equal force of approximately 1100 men should have easily repulsed such an attack. So, why didn’t it? One theory says that Loyalist infantry were unable to shoot low enough due to firing down the hill. However, the British relied heavily upon superior training with bayonets and the dread of ‘cold steel’ that repeatedly sent American militia running for their lives. According to accounts of the battle, Ferguson led several such charges that did indeed send the Overmountain Men crashing back down the slopes. So, why weren’t they more effective?

One theory of mine revolves around the quality of Ferguson’s men. According to Patrick O’Kelley’s order of battle charts from Nothing but Blood and Slaughter, (which I regard as reasonably accurate for discussion purposes), Ferguson only had about 70 experienced and trained soldiers from his own regiment which was chosen from regiments raised several years before in NY and NJ. His other Provincial regiment had been led by Alexander Innes but they were defeated at Musgrove’s Mill. (an almost forgotten yet terribly important battle in August 1780). This left Ferguson with 1,000 raw Tory militia recruited over the summer months. They were green, poorly armed, poorly motivated, and, probably worst of all, Cornwallis had refused to allow any prior Patriots to be recruited which meant that most of the able officers and soldiers (active young men) in the south were not part of the force. We see a number of examples in Cornwallis’s papers where the British officers complained that very few men capable of being leaders or officers in the militia were available. In short, I am going to suggest that, while Ferguson and his small core of men fought well against Shelby and Sevier at the narrow end of King’s Mountain, the other 1,000 men with him hardly fought badly or not at all. I have not run across many accounts of the fighting at that end of the mountain that seem particularly intense. On the other hand, the Patriot force at King’s Mountain consisted of 1100 very experienced individual fighters with an excellent sense of tactics in the forests that surrounded the area.

And that leads to a discussion of Major Ferguson himself. Was he really much of a strategist or did his lack of regard for his own limitations lead to disaster? After all, certainly Ferguson had opportunity to retreat from his position and avoid the battle at King’s Mountain. In a blog post on Patrick Ferguson’s early career, I once wrote:

“The report to Clinton argued the total force necessary to subdue the colonies should be 27,000 but it needed to be made up almost entirely of light troops. The troops would travel in army groups of 12,000 men of which 6,000 would be light troops. Specifically, they would be men “selected for the purpose, lightly equiped, kept in wind & strengthened by constant exercise & employment.” The army would move from area to area creating a temporary base with 6,000 regular infantry. The 6,000 light infantry would then fan out around the “particular district, to gather up all the enemy’s partys, collect carriages, provisions or forage, disarm the inhabitants, take hostages or, if necessary, lay waste the country.” After all, in Ferguson’s opinion, “with regard to the Measures proper to pursue, it is only now become necessary to exert a degree of Severity, which would not have been justifyable at the beginning.” Captain Ferguson doesn’t suggest exactly when the “probability of a friendly accomodation” gave way to a conclusion that further diplomacy was pointless.[vi] However, the sequence of events lends itself to believe the switch probably occurred about the same time Ferguson got wounded at Brandywine. He seemed to lose all sense of empathy regarding the rebel population. His report detailed plans to “demolish Springfield * * * and destroy all the houses, grains & fodder throughout that fertile & populous tract.” Plans were included to “ruin the Granary of New England”, “destroy New London”, and “burn Providence”. He detailed movements beyond that to Boston in a grand attempt to starve the rebels out by “burning of their grains & the depriving their cattle of all means of subsistence during the hard winter of that country.” In this way he would “reduce to great want a people who have always found difficulty in subsisting without foreign supplys.” In short, Ferguson recommended laying waste to the entire country and starving the rebel population into submission. For southern rebels, he added a bit of icing on the cake with “Indians from the Back settlements Added to the Terrors of the Example of New England.” At that point, Ferguson believed the “Republicans would be obliged to beg for bread.”[vii]

Not only did Captain Ferguson’s analysis of August 1778 call for harsh measures against the Patriots but it also reflected a serious lack of respect for his opponents. He said the militia would be so cowed by the presence of the British light troops they would not “walk abroad through the country and the Continentals “must either withdraw or force us into a Battle, which I presume would be the last of the War.” In spite of the strong performance by Washington’s army at Monmouth three months earlier, Ferguson totally dismissed the rebels ability to face a bayonet. Perhaps the one statement that best summed his analysis of the two armies was “that all depends upon the quality of the troops.”[viii] Very interesting that Ferguson himself later forgot all about this rule when placing reliance on his troops at King’s Mountain while a militia force destroyed his army.

Ferguson’s report also showed the beginnings of another trend in his writings. Without regard for any possibility of error or miscalculation, he shows an almost incredible confidence in his own plan by boldly predicting victory by the end of November. Only 4 months from the date of writing.”

Realizing I have likely added too much information, I will pause there and provide an opportunity for more discussion.

Don,

I saw that you replied to Dan this morning while I was writing my reply. Beat me to the punch on mentioning Dan’s 2 cents worth. Anyway, just to add a bit to Dan’s assertion that King’s Mountain may be frequently overrated by authors and historians. I tend to agree. Perhaps not for all of the same reasons but I suspect we cover a lot of the same ground.

In my opinion, King’s Mountain is only one Patriot militia victory in a series of Patriot militia victories that together turned the autumn and winter of 1780 into a very dreary time for Lord Cornwallis. Almost immediately following his victory at Camden, Cornwallis noticed his battle had far less impact on the South Carolina back country than the much smaller Patriot victory at Musgrove’s Mill. It is hard to know exactly why Musgrove’s Mill would overshadow Camden until one considers that the militia and CA regiments with Gates were from North Carolina and Virginia. The local guys were with Shelby, Williams, and Clarke at Musgrove’s Mill so the local bragging rights came to them. While Cornwallis was left wondering why his more significant victory made less impact on the occupation.

September

At that point Cornwallis moved on Charlotte. As Dan suggested in his post, he was not ready for such a move and ran into problems. The biggest problem was probably the annual fever outbreak that sidelined Banastre Tarleton along with entire regiments. The Legion Cavalry found itself commanded temporarily by George Hangar. They refused to charge Davie’s militia at Charlotte and performed very poorly causing Cornwallis to later mention when reporting the battle to his friend, “In regard to cavalry, a detachment of the Legion would hardly answer; they have no officers to command distant detachments, having lost either by the sword or sickness all those of experience, and indeed the whole of them are very different when Tarleton is present or absent.”

Unknown to Cornwallis, earlier in the month of September, Elijah Clarke and James McCall had placed Augusta and Thomas Browne under siege. They came within hours of success when British Lt. Colonel Cruger showed up with a relief column. Augusta was saved but the GA backcountry was aflame.

October

The last straw for the first invasion of North Carolina came in two parts. First, Ferguson’s King’s Mountain defeat left the back country almost defenseless against Shelby and Sumter’s militia regiments and then General Cornwallis himself took sick and had to turn temporary command over to Rawdon. As if those things weren’t bad enough, Elijah Clarke and his siege of Augusta caused the regiments at 96 to pull out for operations in Georgia and Francis Marion had victories at Black Mingo Creek and Tearcoat Swamp.

November

Glory days for the Swamp Fox as he takes Tarleton and the Legion on a merry chase through the swampy low country. Frequently Marion and Tarleton are mentioned together but, to my knowledge, the chase in early November was the only time the two matched wits. While Tarleton chased Marion, Thomas Sumter was busy catching Major Wemyss at Fish Dam Ford while Elijah Clarke and the Georgia Refugees returned from Watauga and joined forces with Sumter. Their combined force menaced the back country necessitating Tarleton’s withdrawal from the chase to go after Sumter in the backcountry.

And so came the Battle at Blackstock’s Plantation. Another little known and misunderstood battle in the partisan war. At Blackstock’s plantation, the Legion cavalry had been held in reserve but was called upon to charge and assist in getting the 23rd out of trouble as their charge ran out of steam. This time the Legion Cavalry did charge but were repulsed by Sumter’s militia who provided some well-placed rifle fire. Apparently they learned the lesson well as the next time they were called upon to charge was a battle called Cowpens, and they refused, to Tarleton’s eternal embarrassment, and the 71st Highlanders total dismay.

December

Following Blackstock’s, Elijah Clarke and Major McCall traveled down into the Long Canes District to recruit from the regiment commanded by Andrew Pickens. With a string of successes to their credit, most of the remaining men in the Long Canes and 96 District broke their paroles and returned to the field. The ultimate result of the Long Canes Revolt would be Cowpens followed by the very successful pairing of Brig Pickens of the South Carolina Militia and Major General Nathaniel Greene of the Continental Army.

Did you notice that I left out King’s Mountain? Anyway, quick summary, the flow after Camden is:

1. Musgrove’s Mill – Shelby, Clarke, & Williams

2. Augusta – Clarke & McCall

3. Charlotte – Davie

4. King’s Mountain – Shelby, Sevier, Campbell, etc.

5. Tearcoat Swamp – Marion

6. Fish Dam Ford – Sumter

7. Blackstock’s Plantation – Sumter, Clarke, Winn, etc.

I don’t see how it could be any easier than that. On the other hand, it seems that many historians, particularly those who undertake complete histories of the American Revolution, tend to lump all of this together and call it, King’s Mountain. To the extent that the designation represents the sum total of all these events, I could not agree more that it belongs on the top ten list. However, to the extent that King’s Mountain must stand alone without the accomplishments of the other engagements? Maybe, but probably overrated on a top ten list.

Dan’s post that originally started me thinking leaned heavily on the idea that the Southern Strategy was defeated by the partisans in 1780, (not 1781) and that King’s Mountain was key in defeating the strategy. I believe that is exactly correct. The southern strategy was already toast before Morgan’s victory at Cowpens. The British had experienced a total collapse at their attempts to build a Tory militia or establish any control in the backcountry. The loss at King’s Mountain was key in completely decimating any semblance of Tory militia. At the end of 1780, even before Cowpens, as Cornwallis was preparing to leave on his 2nd attempt at North Carolina, he was forced to give instructions that no troop movements could be made with less than 125 men. I have recently completed a very interesting research project on a fellow named Moses Kirkland who was from the 96 district. I am not sure of the exact publication date but it comes out soon and provides a very interesting look at how the Southern Strategy may have developed and definitely how it ran its course.

Recently i walked the King’s Mountain battlefield. It is amazing that Ferguson’s command could not hold the high ground with strong natural defenses. It would be daunting to attack up such a steep hill and over uneven terrain into well planned and determined defenses. There must have been a breakdown in loyalist command and control.

Hi Wayne – apologies for the delayed response. I’m pushing through on my last dissertation chapter, which is on these two years. Light at the end of the tunnel!

First, on the question of Ferguson. I know the letter you’re talking about, and it certainly does seem to support the idea of the junior officers (Tarleton, Ferguson, etc) complaining that their superiors had gone soft and the British really needed to take fire and sword to the rebels until they gave up. What’s really interesting is that Ferguson’s tone seems to have changed dramatically in the time between writing that letter and his arrival in NC as he tried to raise militia. I wouldn’t say he started advocating for a kumbaya strategy, but he is much more attuned to the prioritization of organizing loyalist support and forming militia over punitive approaches to the rebels. Some historians tend to echo Cornwallis’s comments on Ferguson (as they do on Cornwallis’s comments on a lot of things – the danger of having a great archival source to rely on!), but Ferguson was much more aware of the requirements of the southern strategy, what it would take to turn out loyalist support, and how to break the control held by the Patriots over the population than many other British officers, and had more success in raising militia than many others. Perhaps he just was not the best option for leading them in potential combat situations.

As for your other comments, I think we’re in agreement. I’m a military historian, like many others that frequent this site, and with experience of other academics sneering at military history – and especially operational history – as useless and irrelevant, I’m fully appreciative of the importance of actual battles, and I love walking the battlefields at Kings Mountain, Cowpens, Guilford Courthouse, etc. What I’m particularly interested in, however, is what went on in between those battles. I think we tend to overestimate the effect of a battle on loyalty one way or the other, because there is so much going on in between those battles that determine the same. I would recommend for anyone who hasn’t already to read the letters of Josiah Martin, the last royal governor of North Carolina, before and after the Battle of Moore’s Creek Bridge in 1776. We know about that battle and how it was over within seconds, and the Loyalists/Highlander force decimated and dispersed. But if you read Martin’s letters you become aware of the extent to which the Patriot forces had extended their control over the country and population between Cross Creek and Wilmington to the point where they knew as soon as the loyalists began assembling at Cross Creek and took action to reduce their numbers, they used strategic movement of their own forces to shadow the Loyalists and Highlanders along the march from Cross Creek, thereby reducing the numbers further as Loyalists were intimidated into leaving the march and returning home. They took control of certain passes and bridges to force the Loyalists along the route they wanted them to take. They intercepted all of the messengers Martin sent to the loyalists in the backcountry to coordinate the operation, and even infiltrated Martin’s network of messengers and emissaries to disrupt his communications with the loyalists and feed him bad information. The result was that Martin – who was supposed to be waiting in Wilmington with support for the Loyalists and Highlanders – had no idea where they were, whether they had marched yet, what their progress was, or that they had been crushed by the Patriots at Moore’s Creek Bridge. As a result the Loyalists were left isolated and exposed, and Martin was able to provide no support. The Patriots had spent the previous months extending this system of population control using force, propaganda, more lenient measures, and by working from within the royal provincial government to weaken government authority. This process allowed them to control countless loyalists and prevent them from supporting the British before the battle at Moore’s Creek Bridge even occurred. While the battle itself was indeed important, it would be wrong to say that the absence of Loyalist activity after March 1776 was entirely, or even predominantly, due to the outcome of that battle. The patriot governments and militia were applying the use of coercive force – along with other means of control – on a near daily basis by that point, which often gets overlooked in histories of the war in the South.

I think this also helps partially explain Wayne’s observation that Patriot victories may have had more of an effect on public opinion and loyalty than British victories. The Patriots were aware that the British strategy required active Loyalist support, and so sought to prevent the British from implementing that strategy by controlling the population themselves. They knew the war was among the people, while the British thought the population whose support they needed were just passive actors responding to their great conventional victories. Therefore after their victories the Patriots sought to drive the point home among the population, while after Camden, for example, the British largely ignored the population as they spent weeks preparing to move into NC. I think Wayne’s point about the Patriot militia at Musgrove’s Mill being local is right, and that gave them a decided advantage in working the local population.

As I mentioned I’m working on my last dissertation chapter now, and in building my outline I noticed that by the end of July 1780 (so before just about any reasonable-sized battle in the backcountry with the exception of Ramsour’s Mill, Mobley’s Meeting House, and Huck’s Defeat), Waxhaw, Cheraw, Georgetown, and even Ninety Six districts were all reporting serious disaffection, Patriots moving in and out of the districts with impunity, serious issues trying to form militia and provincial corps, and populations that were essentially waiting to see which side prevailed.

Then there was Georgia, which was still a mess, and James Wright was begging Cornwallis to establish a few more posts, or give him some cavalry to patrol the backcountry to isolate the enemy from the population. Cornwallis simply replied each time that there could be nothing wrong with Georgia because they were fully in control of South Carolina, as if Wright were simply imagining his province falling apart. So the idea that King’s Mountain was responsible for ending loyalist support for the British just doesn’t seem to hold water. Without trying to be deterministic, the southern strategy was falling apart in 1779, when Archibald Campbell and Augustine Prevost kept ignoring the purpose of the strategy – organizing Loyalist support – in favor of doing what they were more comfortable doing – chasing the main Patriot army all over Georgia and South Carolina. Many of the mistakes and problems of 1780-1781 were made first in Georgia in 1779.

I look forward to your study on Kirkland. He’s an interesting character – I follow him in my dissertation beginning with his time as a backcountry loyalist leader in 1775 (after defecting from the Patriots). The Patriot effort to pacify the backcountry in the summer and autumn of 1775 was much more impressive than most historians give them credit for. They targeted both loyalist leadership and loyalist populations to force the latter over to their side and force the former (particularly Kirkland) on the run by leaving them exposed and without any followers. William Henry Drayton maneuvered the surrender of a sizable loyalist force near Ninety Six without firing a shot. This resulted in the removal of several key loyalist leaders from the battlefield, ending the threat they posed and weakening the remaining loyalist holdouts, which Andrew Williamson and Richard Richardson took care of later in the autumn at Ninety Six and in the Snow Campaign. All in all a very successful pacification effort that resulted in the arrests of numerous loyalist leaders, and forced others to flee to the Cherokee nation or (in the case of Kirkland) to the North.

Dan,

Thanks for the stimulating correspondence. I am not sure about being a military historian or an academic sneering at military history but my approach to the southern campaigns has always been to focus on an individual or group (regiment) and follow them through the action. Perhaps I am a biographer stuck in a particular time period continually choosing to change perspective to different actors in the same play.

With that same emphasis in mind, I was fascinated to spend some time considering your thoughts on Major Patrick Ferguson, a fellow I have looked at before. In my research (certainly largely influenced but not completely limited to the Cornwallis Papers), it appeared that Ferguson arrived in South Carolina full of much the same overconfidence and lack of respect for his opponents that showed in the letter to Clinton. His very first report Ferguson hopes his role as Inspector of Militia “will be attended with very important and probably decisive advantages with regard to the southern provinces at a small expence.” After all, from what Ferguson has heard there is “no reason to doubt that the inhabitants are very well disposed to take an active part”. He went on to opine that his Tory militia “may render it unnecessary” to garrison large numbers of troops in the southern states. Ferguson enclosed a Hand Bill to the population in which all the men would serve in the militia (without regard to prior service as Patriots) and parole terms would be quite generous.

To be honest, my observations of overconfidence and severe bias toward Patriots are influenced not only by the letters to Clinton recommending extreme measures against the population, but also by Ferguson’s subsequent actions. Only two months afterwards, Ferguson led his men on a raid to Little Egg Harbor during which Ferguson gave an order of ‘no quarter’ in a night assault against Count Pulaski’s sleeping legion. I lifted these paragraphs from an earlier blog post:

“A few days later a very questionable incident occurred involving Major Ferguson. He received information the infantry companies of Count Pulaski’s Legion were quartered in three houses. Ferguson planned a night assault that took place at 4am. Caught unprepared, the rebel infantry suffered about 50 casualties of whom, none survived. Ferguson famously explained “It being a night attack Little Quarter could of course be given, so there are only 5 prisoners.” Total casualties for the British were one dead, one missing (possible deserter), and 3 “slightly wounded”. Ferguson later offered different justification for the action by explaining “deserters inform us that Mr Polaski has in publick Orders lately directed no Quarter to be given, & it was therefore with particular satisfaction that the detachment marchd against a Man Capable of issuing an order so unworthy of a Gentleman & a Soldier.” He went on to conclude that all his men, “both British and provincials, on this occasion behaved in a manner to do themselves honor.”

Certainly not everyone bought into Ferguson’s explanation for the harsh treatment inflicted upon Pulaski’s men. In his sketch, An Officer out of his Time: Major Patrick Ferguson, Hugh Rankin says, “Although Clinton expressed his approbation of the exploit, another Scots officer held the opinion that ‘These sort of things will never put an end to the war’.” Rankin also brings out the fact Patriot accounts of the incident indicate death counts up to 250 instead of only the 50 men indicated by Ferguson. Regardless of whose number is correct, the record seems pretty clear that Ferguson gave orders of ‘no quarter’ for the assault upon Pulaski’s sleeping men. The unrealistically low number of British casualties does not indicate a struggle but a complete surprise in which each of Ferguson’s 200 men had an opportunity to bayonet a sleeping rebel while the lucky others ran off into the night.”

Since the writing of those paragraphs, I did some research into an officer named Captain Dunlap. While serving under Simcoe in the Queen’s Rangers a short time prior to Little Egg Harbor, Captain Dunlap played a prominent role in a similar engagement at Hancock House which was another incident in which rebels had been caught sleeping and put to the bayonet. Not only does Ferguson appear to have copied that incident but he later chose Dunlap to accompany him to South Carolina for the Southern Campaign.

In his writings subsequent to Little Egg Harbor, Ferguson continued to estimate the Patriot influence estimating active Whigs at less than 10% of the population. Even while presenting a plan to maintain discipline in the ranks to contain the practice of looting, he limited that protection only to the loyalist population. The Whigs would find their property systematically liquidated and divided among the regiments involved. . “By this means the soldier would at times be gratified by a just booty without hurting discipline, and military execution.” Consistent with many of the British conservatives, Ferguson estimated “persons under this description, altho’ they may possess a large proportion of the property of the continent, are not certainly one tenth part of their numbers.”

Back to Lord Cornwallis on June 2, 1780

Lord Cornwallis was distinctly unimpressed with Major Ferguson’s plan and quickly clipped Ferguson’s wings. He didn’t fail to grasp the importance of establishing the militia but he was still “forming a plan for that purpose. . . In the mean time I must desire that you will take no steps in this business without receiving directions from me.” Most notably, Lord Cornwallis was unhappy at the use of prior Patriots in the militia and ease by which the people were freed from parole. He would later insist upon arrest and confinement for the Patriot leaders. I’m sure he was further influenced by the opinion of Nesbit Balfour who was in command of the columns that included Ferguson’s men. “As to Ferguson, his ideas are so wild and sanguine that I doubt it would be dangerous to entrust him with the conduct of any plan” and there should be no rush to establish a new administration without better knowledge about the “people who are your friends – foes.”

Up to that point, I don’t see much change in Ferguson’s outlook. However, following Cornwallis’s rebuke, Ferguson went into a sullen period and quiet period. A week later, he got a follow up letter with instructions after which Major Ferguson turned his attention to his work. He was always a hard worker with a lot of ambition. Balfour described, “We are on good terms, but as I do not communicate or follow his ideas entirely, of course, I do not expect his exertions, although I beg leave to assure you that he has been ready on all occasions when he was desired, and has done what he could to keep his people in order, in which he and the rest of the corps have succeeded wonderfully.”

Unfortunately, the time in Cornwallis doghouse didn’t cure Ferguson of his overconfidence. “. . there will be a militia in this province soon form’d upon the foundation of a free association, much more numerous and ten times more to be trusted than any the rebels evert turn’d out.” Ferguson also displayed a bit of that stuff some historians might tend to think makes him a bit of a brownnose. Easily adapting to Clinton’s absence and shifting to the thinking of Lord Cornwallis, he said “the militia will be infinitely more to be trusted to, more willing and indeed more strong if they are allow’d to reject men of doubtful characters and if your Lordship’s instructions about imprisoning very obnoxious criminals is steadily followed.” I’m not personally certain this passage should be viewed so negatively but it is thought provoking. In all the reports and correspondence from Ferguson, I don’t think his commanders ever got information that wasn’t biased with optimism to the extent as to be worthless or misleading, mostly due to his refusal to see any possibility that the enemy might be capable of throwing a wrench in his plans.

Now, I’m sure I have ripped into Major Ferguson pretty good with these observations and I do so with a reasonable (probably overconfident ) belief they are accurate. However, in an overall description of Patrick Ferguson, I would agree that he was probably a good choice for the job of organizing the militia regiments. Certainly he should adopt a more realistic attitude toward their limitations (and his own) but Ferguson was a very active officer who, regardless of having been rebuked, continued on in his duty and followed his orders to the best of his ability. I understand that he was ambitious to the point of being thought a sycophant by some of his peers. I also believe he was a charming man who enjoyed the company of women. He seems gallant in his protection of loyalist women and also in the famous episode where he claims to have spared George Washington simply because he was an unknown officer Ferguson admired for coolly taking care of business in the heat of battle. I am not sure I see any change or softening toward the rebel population even though it appears that Clinton (and later Cornwallis) remained adamant that the Loyalist population be protected from plundering or abuse from the troops.

Hmmm, I seem to have typed a good deal of the morning away. I appreciate the opportunity to converse with such a learned fellow. I hope your dissertation continues to go well. While I have certainly written enough for this morning, I hope to return soon with another response. Perhaps concerning the situation in Georgia during that wild Summer of 1780. I would be delighted to hear more thoughts on Ferguson, I do not hold my opinions out as authoritative, absolute, cast in stone or any such thing. Always interested to look at a new perspective on such a prominent player in the southern campaign.

Wayne

Hi Wayne,

Lots of good thoughts there. A few quick responses.

1. I don’t mean to say Ferguson had it all figured out. I don’t particularly feel one way or another about him. I just think historians in general (not at all referring to your comments or articles) have relied too much on and run with Cornwallis’s opinion of people. So people he didn’t like (Ferguson, Kirkland, James Wright, Thomas Brown, etc) have generally come off poorly in the historiography, while those he liked (Balfour, Rawdon, Innes, etc) come off in a more favorable light. That latter group I don’t have any problems with, but the former group doesn’t usually deserve the reputation they’ve gotten from historians. This is not an argument against using the Cornwallis papers – they’re an incredible source. I just think as one reads them in their entirety, it becomes clear that there was a lot going on that Cornwallis was clueless about, or simply didn’t understand, and sometimes (not always) the other guys were not the dunderheads he thought they were.

As I think I mentioned, the one who I think had a much better understanding of what was going on than Cornwallis was James Wright. He generally understood the way the Patriots’ strategy worked, and he was constantly on Cornwallis that perhaps the reason he was having so much trouble in SC was because Georgia was a total mess. Cornwallis thought he was nothing more than a nervous nelly. You can almost picture him rolling his eyes in exasperation when you read his replies to Wright. Time and again he denied Wright’s request for posts along the Savannah River, for horse to patrol the backcountry, and for military forces to cover the Georgia backcountry and focus on breaking the control the Patriots held over the Loyalists. Cornwallis insisted that the post at Ninety Six meant that there could be absolutely no problems or Patriot activity in Georgia, and to stop bothering him already. He couldn’t have been more wrong.

2. Regarding Ferguson’s overconfidence – absolutely! And he wasn’t the only one. Nearly every British officer, political official, and government official back in London were absolutely positive that next action (a march, a proclamation, a battle, whatever) would be the thing that broke the Patriots for good. The absolute worst offender in this respect was George Germain. Even allowing for the fact that he was across the ocean trying to keep up with what was happening, and that he was in a precarious political position in London, you can’t help think he was to some degree losing touch with reality – desperate for things to be turning out favorably and ignoring the reports that said otherwise. After Augustine Prevost marched to Charleston from Savannah in April/May 1779, and reported back that almost no Loyalists showed up to join his army, leaving it too weak to take and hold the city, he reported the lack of Loyalist turnout to Germain. Sometime later, after he had received Prevost’s letter, he was ruminating about the planned expedition to take Charleston, and cited all the Loyalists that showed up during Prevost’s march as evidence of how well everything was going to work. Cornwallis did this a LOT too. He was constantly “certain” that after this or that skirmish or battle there could be no Patriot parties left in Ninety Six, in Georgetown district, in Waxhaw, etc., and he often dismissed any reports that said there were.

3. Regarding paroles, protections, arrests, pardons, etc. The Patriots had a better understanding of how to use these to their benefit in terms of their political objective – controlling the population. The British did not connect them to the same political objective as well. The Patriots, by and large, had a “with us or against us” attitude. If a Loyalist was willing to take the oath of allegiance, join a militia unit, and so forth, the Patriots were happy to let them do so. They weren’t naive though – they knew many would abandon them as soon as the British gave them the opportunity to do so. They would demand active support from these Loyalists, often to get them “involved” in the rebellion as well, giving them few options but to continue supporting the Patriots (think of it as sort of an 18th century version of a gang initiation). But the oaths also served other purposes – it was a type of census that allowed the rebels to identify who was who, track movements, and quickly determine whether someone was friend or foe. Those that wouldn’t take the oath generally either fled to Georgia or the Indian territory, moved to the West Indies or to the North, or were arrested. Even when they were given their parole, they were watched extremely closely. They had to check in regularly with a local Patriot leader, could not travel more than x miles from their home or place of parole, and were generally disarmed.

The British saw the concept of a parole in a much more traditionally military sense – as a way to remove numbers of the enemy, or potential enemies that they had to worry about. They saw almost none of the political element that the Patriots did. It was not about controlling the population, but about defeating the enemy’s army on the battlefield. Their system of parole was also much more complex than that of the Patriots, with more poorly defined categories of status and they made little effort to coordinate a mutual understanding of each category among all officers who had responsibility for giving them out. As a result, you had one person issuing paroles, and someone else coming along shortly thereafter to cancel them and arrest the person. Paroles in SC were not always recognized in Georgia. Former Patriots were not to be included in the militia, but many ultimately wound up in the militia. The difference between this and the Patriots incorporating former Loyalists into their militias was that the Patriots did so deliberately and with purpose, and knew they had to keep watch over these individuals. The British often had no idea who these people were, that they were former Patriots, and therefore did not know to keep a close watch over them if they did end up in the militia. Thus they armed Patriots without taking the extra step of either “trapping” them into supporting them or keeping close watch over their actions. Their different categories of status for former Patriots also got so convoluted that the punishments started to make comparatively little sense. A Patriot who had joined the British and somewhere along the line went back to the Patriots often got a more lenient sentence than someone who had supported the British all along and then defected to the Patriots. This ignored the fact that the former probably never had any allegiance to the British at all, while the latter probably did. It also showed a lack of understanding that a true Loyalist might not have had a choice when they agreed to support the Patriots. This was in general the British problem – a lack of appreciation for why inhabitants supported the sides they did, and how to leverage potential Loyalist support.

In other words, everything the Patriots did was towards a political end – keeping control of the population and preventing as many Loyalists as possible from supporting the British. The British, for their part, acted haphazardly, with little in the way of formed plan or coordination, and with no general understanding of the ends sought – and particularly little appreciation for the political nature of those ends. The Patriot approach was much less subtle, much less sophisticated, and even less legal and liberal. But it was much more effective. Ben Franklin’s famous saying about liberty and security aside, many political and military leaders in the war were aware that the measures they took did not always square with constitutions and liberalism, but argued that they were necessary to secure such over the long term.

I realize I said “quick responses.” Looks like I lied 🙂

Regarding the Battle of Kings Mountain, an article was written by Gen. John Watts de Peyster, nephew of Captain Andrew de Peyster entitled, “The Affair at King’s Mountain.” This was included in “Andrew Jackson and Early Tennessee History” published in 1921. “The Affair at Kings Mountain” gives the British account of the Battle published in 1880. In this account, Gen. John Watts de Peyster asserts that Maj. Patrick Ferguson was shot early in the action not at the end, as is often presented. He says that Ferguson may have burst through the lines near Cleveland’s ascent of the hill exposing him to gunfire. The crux of the article is that de Peyster didn’t hide and surrender when Ferguson was killed but fought gallantly until he had no other choice but to do so. While I cannot attest to the truth or motives of this account, it does give us a different perspective and might explain why the British lost this battle.

This was very helpful, because in my history class we are writing a book about the American Revolution. It gave useful information, pictures, and explained the battles really well. All the other websites I have went on have given me useless information, unlike this website! Thank you so much and I will subscribe!

I love history, just like my mom.

Although it didn’t include the Continental Army, the Great Siege of Gibraltar is probably the greatest battle of the entire war and one of the greatest underdog victories in history. One year after Saratoga, Benjamin Franklin managed to persuade France into joining the revolutionary cause in 1778, and later on in 1779, Spain declared war on Great Britain as well. In that same year, Spain besieged the British peninsular fortress of Gibraltar. The garrison held off several probing attacks while the Royal Navy succeeded in sending convoys to the peninsula and evacuate the civilians. Despite these successes the siege was not lifted. When food shortages settled in again and morale plummeted, the governor, George Augustus Eliot, ordered a sortie on the Spanish forces in the isthmus. The British and Hanoverian troops successfully defeated the defenses and blew up the magazines. Then, in 1782, the Spanish, with French reinforcements, decided to end the siege once and for all. They had concentrated a large amount of troops and warships in preparation for the ‘Grand Assault.’ But the English had one invention that would decide the fate of the battle–George Koehler’s depressing carriage. The result was a military failure for the attackers. Still, it continued to be under siege until the Royal Navy lifted it in 1783. Being largely outnumbered, it came as a spectacular victory for the Anglo-German defenders, but it is largely overlooked concerning Americans.

As described in the introduction, this list of top ten battles considered only those fought in North America. For more about the Siege of Gibraltar, see our article here.

Oh…didn’t see that😏

Great article(s) by the way.

Defense of the Delaware. This includes the Battle of Red Bank and Ft. Mifflin and Ft. Mercer aka the fort that saved America.