Most have heard of Timothy Murphy and the shooting of Brigadier General Simon Fraser. However, how many have heard of Benjamin Whitcomb and the shooting of Brigadier General Patrick Gordon? Hugh Harrington in a March 25 submission to this magazine has shown the former to be mythical. The following will show the latter to be fact.

Born in Lancaster, Massachusetts, in 1737, Benjamin Whitcomb served in a Massachusetts regiment during several campaigns of the French and Indian war. After the conflict, he moved to southern New Hampshire and Vermont and then to the Coös region of the upper Connecticut River. In January, 1776, he moved his family back to southern New Hampshire and received a commission as a lieutenant and recruiting officer in Samuel Young’s Company of Timothy Bedel’s New Hampshire Rangers. In the early spring, he took his recruits to join the regiment in Canada and made it back to Ticonderoga at the close of the disastrous Canadian campaign.

Once the “Retreating, Raged, Starved, lousey, thevish, Pockey Army”[1] settled in at Ticonderoga, American commanders asked for scouts to watch enemy activities around Montreal, over 100 miles down Lake Champlain. Whitcomb immediately volunteered. The 39-year-old lieutenant had the qualifications for the role as scout. In addition to having learned the geography of the Champlain valley during his earlier service, he had the necessary physical and personality traits for such hazardous duty. According to Frye Bailey, one of his contemporaries, “Whitcomb was a presumptuous fellow, entirely devoid of fear, of more than common strength, equal to an Indian for enduring hardship or privation, drank to excess even when in the greatest peril, balls whistling around his head.”[2]

On July 14, 1776, Whitcomb set out for Canada with four men. Two Frenchmen with him became nervous and turned back after questioning some residents near the British fort at St. John on the Richelieu River. Another man became ill and left for Ticonderoga. After noting the activity at St. John, Whitcomb moved deeper behind enemy lines with his sole remaining companion who soon deserted. Alone, Whitcomb remained in the area watching traffic on the roads from St. John to Montreal and Chamblee. In his journal of the mission, he nonchalantly described what happened next:

24th stayed at the same place till about 12 o’clock then fired on an officer and moved immediately into Chamblee road. Being discovered retreated back into the woods and stayed till night, then taking the road and passing the guards till I came below Chamblee. Finding myself discovered, was obliged to conceal myself in the brush till dark, the 25th instant, on which I made my escape by the guards.

Not making another note of the shooting in the report, he did not learn the full story of his actions until he returned to Ticonderoga on August 6.[3]

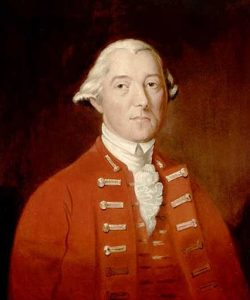

Lieutenant Whitcomb had shot Brigadier General Patrick Gordon, lieutenant-colonel of 29th Regiment. Earlier that spring, Gordon had been appointed commander of the 1st Brigade in Canada which consisted of his own regiment along with the 21st and 62nd Regiments. On the morning of July 24, Gordon had left brigade headquarters at La Prairie to visit one of his other posts, St. John. Not suspecting any trouble this far from the rebel positions, he made the trip alone but, just a short distance from the post, he received two balls in his shoulder. He remained on his horse and made it to the fort.[4]

It did not take long for Canada’s Governor-General Guy Carleton to issue a general order which said, in part:

The Rebel Runaways not having dared shew their Faces as Soldiers, have now taken the part of the vilest Assassins, and are lurking in small parties to Murder, if possible, any single or unarmed officer, or soldier, who may be passing the Roads near a Wood side. B.G. Gordon was dangerously wounded yesterday by one of these infamous Skulkers. … Should he, or any of his party, or any other party of the same Nature come within reach of our Men, it is hoped they will not honor them with a Soldier’s Death, if they can possibly avoid it, but reserve them for a due punishment, which can only be inflicted by the Hangman.[5]

General Gordon died on August 1 heightening the British feelings of enmity toward Whitcomb who had been identified by the man who had deserted him. Subsequently, Carleton issued a reward of 50 guineas for Benjamin Whitcomb, alive or dead.[6] The offer would remain in effect for the remainder of the war.

It is obvious that the British considered the attack dishonorable, a serious imputation in a time when people held honor in high regard. One British officer lamented that, “[t]he Rascal Whitcomb escaped but time perhaps may bring him to the End, which his murder of B. General Gordon deserves.”[7] The vehemence of this statement is lost on any reader who does not know that the eighteenth-century Englishman understood the term “rascal” to be perhaps the strongest pejorative name one person could call another. The comment demonstrated the genuine loathing of Whitcomb felt by his enemy.

The British condemned the act, in part, because they considered it against the rules of war. Whitcomb may have had similar feelings towards the British and their Indian allies based on reports of the brutal treatment of prisoners taken at the Cedars. As a result of those stories, Congress on July 10 had passed a resolution stating that if the enemy committed any more acts such as that done at the Cedars, then an equal number of prisoners held by the Americans would suffer the same fate. Although it is doubtful that Whitcomb knew of this resolution, similar sentiments pervaded the American army that summer.[8]

Whitcomb’s action upset more than just the British. When Washington heard of the incident, he called it an “assassination” and went on to say that the incident was “highly unbecoming the Character of a Soldier and Gentleman.”[9] Colonel Matthew Ogden agreed when he wrote to Aaron Burr about the British reaction to the shooting but added admiringly, “[t]he act, though villainous, was brave, and a peculiar kind of bravery that I believe Whitcomb alone is possessed of. He shot Gordon nearby their advanced sentinel; and, notwithstanding a most diligent search was made, he avoided them by mere dint of skulking.”[10]

A small number of people claimed robbery to be a motivating factor for Whitcomb. In a letter to Abigail Adams, Adjutant Nathan Rice wrote, “having also a great fancy for his Watch and Sword as he says, he fired upon him.” One or two others made similar statements but Rice is the only one who claimed that Whitcomb said he wanted the items. In any event, nothing more ever came of the comments. [11]

It is interesting to note that those Americans who condemned Whitcomb all belonged to the officer corps—possibly because they feared a similar fate at the hands of British scouts. Journals and diaries of the fighting men, however, made no mention that Whitcomb’s actions deserved censure. James Wilkinson, an aid to General Horatio Gates, called him an assassin and hinted that he had planned to rob Gordon. Furthermore, “[t]his abominable outrage on the customs of war and the laws of humanity, produced a sensation of strong disgust in the army, and men of sensibility and honour did not conceal their abhorrence of its perpetrator.” It is likely Wilkinson is referring to the officers of the army for he concluded his commentary with a nod to enlisted men by saying, “[y]et it was impossible, in the temper of the times, to bring him to punishment, without disaffecting the fighting men on that whole frontier.”[12]

Wilkinson’s choice of the phrase “the temper of the times” is captivating. What was he referring to? Because there existed a distinction between the officers and the enlisted men, and because of England’s class structure, to a certain degree, induced the Revolution, Wilkinson may have been referring to a reaction against that distinction. His allusion may also have referred to feelings about the Cedars affair. Whatever the stimulus, here was one of Whitcomb’s strongest detractors hinting that the shooting was not so terrible when considered in context.

Even though a high percentage of American officers condemned Whitcomb for the shooting, others felt the British use of Indians and their bloody kind of war justified such retaliation. Nathan Rice closed his commentary by writing, “[t]his seems rather Murder, but it is treating them only in their own Way.” Some even felt genuine concern for the scout’s well-being. General Arthur St. Clair later put his anxiety down on paper: “I shall send off Whitcomb himself presently, for intelligence I must have, altho’ I am very loth to put him upon it, lest he should fall into the hands of the enemy, who have no small desire to have him in their power.”[13]

The incident also made a name for Whitcomb among the Crown forces. The commander of the German troops, Major General Baron Friederich Riedesel, made note of the incident in a letter to Duke Charles of Brunswick. In it, Riedesel commented on how easily the enemy could sneak into the camps and it amazed him that “the rebels could make this long march of forty leagues [a German league is 3 miles] through deserts and dense woods, and carry, at the same time, rations for fifteen days on their backs.” Riedesel’s comments succinctly illustrated the value of rangers in North American warfare.[14]

The shooting of Gordon prompted immediate changes in British operations. Now aware that American scouts could penetrate deep behind their lines, the light infantry received orders to move forward a few miles and occupy Isle Aux Noix in an attempt to capture the brazen scouts before they came close to St. John or Montreal. At the same time, a force of 300 Indians and Canadians assembled to attack the area around Crown Point.[15] In addition, each camp received orders to have a party of men, over and above the regular guards, ready at all times to immediately go in pursuit of any enemy reported in their area.[16]

As well as much more vigilant, the British became considerably less forgiving of the rebelling Americans. At the same time as Gordon’s death, a flag of truce from the Americans arrived in Canada—a flag that Whitcomb could not have known about since he had been in Canada for two weeks. Because the shooting had left General Carleton in no mood to discuss anything with the rebels, let alone peace, he issued orders stating that, “Letters, or messages from Rebels, Traitors in Arms against the King, Rioters, disturbers of the public Peace, Plunderers, Robbers, Assassins, or Murderers, are on no occasion to be admitted.” Any papers the messengers carried were not to be delivered or even opened. Rather, they were to be “burnt by the hands of the common Hangman.” Gordon’s shooting turned Carleton against receiving any messages from the Americans, something he had willingly done previously.[17]

In the early years of the war, many Americans and British still saw reconciliation as possible and desirable. However, as a result of Governor-General Carleton’s orders, any messages—messages which might have dealt with reconciliation—now went unread. It is interesting to ponder whether or not the British in Canada would have considered reconciliation messages if Gordon had not been shot.

Memory of the shooting—and the reward—did not quickly fade away. St. Clair expressed his concern for Whitcomb’s well-being nearly a year after the shooting. That same summer, two men carrying a message under a flag of truce “were detained by British authority as spies nearly one whole year by reason of offence taken by Genl Carleton in consequence of the death of Col. Gordon.”[18] These men, merely acting as messengers under a flag of truce and not even remotely involved in the shooting of Gordon, nevertheless, suffered imprisonment because of it. In October, 1780, a party of 300 Indians and a few British that raided northern Vermont had as one of its objectives to capture Whitcomb. The next year—after Whitcomb had left the army—Indians captured him only to have him escape the night before being turned over to the British military.[19]

Whitcomb suffered little, if any, mental or physical anguish from either the threat of British vengeance or the derision given him by some of his fellow officers. Less than a month after shooting Gordon, he returned to the same place (this time with orders to shoot only in self-defense) and captured the quarter-master and his aide from the 29th Regiment, the same regiment Gordon served in. After struggling through the wilderness, Whitcomb turned the captives over to General Gates. As a result of his prowess as a scout, Gates recommended to Congress that Whitcomb be promoted to captain and given two companies of rangers. Congress complied and Benjamin Whitcomb’s Independent Corps of Rangers began service in October, 1776, and functioned as scouts and spies until early in 1781.

In the late summer of 1776, many people on both sides of the conflict knew about the shooting of Brigadier General Patrick Gordon. Numerous letters telling the story had been sent home and accounts of the incident had appeared in newspapers. Unlike the myth of Timothy Murphy, few historians have picked up the story in the years since. Worse, what little has been written falls into the same vein as the myth—inaccurate as it occasionally places Gordon’s shooting at the wrong location[20] and somewhat misdirected as it emphasizes the claim that Whitcomb intended to rob Gordon. Regrettably, the true story is nearly lost to history or distorted by the passage of time. Hopefully, some of that is now rectified.

[1] Jeduthan Baldwin, The Revolutionary Journal of Col. Jeduthan Baldwin 1775-1778, ed. Thomas Williams Baldwin (Bangor, ME: The De Burians, 1906), 60.

[2] Frye Bailey, “Colonel Frye Bailey’s Reminiscences,” in Proceedings of the Vermont Historical Society for the Years 1923, 1924 and 1925 (Bellows Falls, Vermont: Vermont Historical Society, 1926) , 55.

[3] Peter Force and M. St. Clair Clarke, eds. American Archives: Fifth Series (Washington, DC: 1848-1853), 1:828.

[4] William Digby. The British Invasion from the North. The Campaigns of Generals Carleton and Burgoyne from Canada, 1776-1777, Munsell’s Historical Series, No. 16. (Albany, NY: J. Munsell’s Sons, 1887), 129. Whitcomb apparently had two balls loaded in his musket, a not uncommon practice at the time.

[5] George F. G. Stanley, For Want of a Horse (Sackville, New Brunswick, Canada: Tribune Press, 1961), 79-80.

[6] Thomas Anbury, With Burgoyne from Quebec, ed. Sydney J. Jackman (Toronto: MacMillan of Canada, 1963), 113. A guinea is twenty-one shillings. A shilling is 12 pence. The base pay of a private was eight pence per day. The reward therefore equaled 1575 days’ pay at the base rate of a private.

[8] James Murray Hadden, Hadden’s Journal and Orderly Books, ed. Horatio Rogers, Munsell’s Historical Series, No. 12. (Albany, NY: J. Munsell’s Sons, 1884), 100-101.

[9] George Washington, The Papers of George Washington, sen. ed. Dorothy Twohig (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1993), letterbook 10: 3026.

[11] Nathan Rice, Ticonderoga, to Abigail Adams, Braintree, Massachusetts, 7 August 1776, Founding Families: Digital Editions of the Papers of the Winthrops and the Adamses, ed. C. James Taylor. Boston: Massachusetts Historical Society, 2007: http://www.masshist.org/publications/apde/portia.php?id=AFC02d053 (accessed 7 May 2011). The charge appears in some secondary works dealing with Whitcomb.

[13] Proceedings of a General Court Martial … For the Trial of Major General St. Clair (Philadelphia: Hall and Sellers, 1778; reprint, New York: New York Historical Society, 1881) 122.

[14] Major General Friederich Riedesel, Memoirs and Journals of Major General Riedesel During His Residence in America, trans. William L. Stone (Albany, NY: J. Munsell, 1868), 1:244.

[18] Isaac Hammond, ed., The State of New Hampshire: Rolls of the Soldiers in the Revolutionary War. 4 vols. (Concord, NH: State of New Hampshire, 1885), 4:469.

5 Comments

It is ironic, yet true throughout history, that individuals like Wilkinson would express such moral and ethical outrage in view of his own lack thereof as well documented in his personal history. In particular his role as a paid Spanish agent while a senior commander in the American Army after the Revolution. Wonder how Benedict Arnold reacted to the incident?

I think Wilkinson, and his writings, have to be taken with a large dose of skepticism. He is one of the great self-promoters and schemers of our history. And, we’ll probably never really know all that he did, or hoped to do, as he wasn’t often successful. Unless his accounts are backed up by other, more credible witnesses, then I almost literally put an asterisk by them; sort of an “unverified” flag for future reference.

A little known single source tale from North Carolina:

In the early spring of 1781 Major Craig of the 82nd regiment in Wilmington made a habit of riding out in the afternoons with a troop of 12 to 15 dragoons. They would normally make a fairly formidable force for the local militia but Captain James Love and his friend William Jones noticed a dangerous pattern. It seemed that each afternoon the Major would lead his men single file over a narrow bridge a few miles from town. A perfect spot to pick them off one by one.

Love and Jones led a small group (about 25) men to stake an ambush at the site. Unfortunately the militiamen got cold feet at the approach of Major Craig and the dragoons. They ran off into the bushes leaving only Love and Jones. Love wanted to take a shot at Craig but let Jones talk him down as it was suicide for the two of them acting alone.

Later the men all got back together at Rouse’s Tavern for a good laugh and bragging session. Even though they knew better than to stay long, everyone got drunk and went to sleeping an the floor. Major Craig got wind of the situation and surrounded the tavern. Only James Love heard them coming and jumped up. He tried to fight his way out with a sword but the British backed him up to a mulberry tree and cut him down with bayonets. They followed by storming the tavern and killing the other 11 men who were mostly still intoxicated. The tavern floor was “covered with dead bodies and almost swimming in blood & battered brains smoking on the walls.”

Now Captain Love had a good friend in the area named Thomas Bludworth. Thomas was particularly upset about the Rouse Tavern massacre and swore he would kill all the redcoats he could as personal revenge.

Bludworth had skills as a gunsmith and secretly made a large long-range rifle. He practiced with the weapon until he could hit the outline of a man at distances previously unheard of. He then went hunting in the area around Wilmington. While chasing a fox, Thomas came across just what he wanted, a giant hollow cypress tree over 7 feet in diameter.

Bludworth returned to the spot with a couple of helpers and camped out inside the tree. At 11am each morning the British soldiers lined up for the rum ration near the edge of town. Bludworth stationed himself just right and waited for enough wind to hide his shot. Soon he got the chance and picked off 3 dragoons one by one before a search started.

They stayed hidden in the tree while Major Craig searched in vain for the murderous whigs. He never thought to look as far away as the cypress tree.

Letting things settle down Bludworth waited three days before popping off a couple more soldiers. This time a local Tory whispered to Craig to expand his search and cut all the timber as far as he could see. The British started their task and almost got to Thomas’s tree before nightfall but stopped just short. During the middle of the night, Bludworth and helpers impersonated a wild hog and escaped into the forest.

Just a small addition, Hugh and I were part of a discussion on this story once before in a forum.

http://www.armchairgeneral.com/forums/showthread.php?p=2633853#post2633853

The author makes a good point about the outrage expressed by officers on the Revolutionary side reflecting their fear of being targeted by a sniper themselves. Had Whitcomb shot an ordinary rank-and-file soldier in exactly the same circumstances, I doubt that an eyelid would have been batted by anyone.