Thanks to the numerous promotions of military leadership before, during and even after the Revolutionary War, senior military ranks tend to cause great confusion for historians. Surprisingly, one of the most puzzling American military ranks is that of George Washington. As the result of multiple post-war appointments and promotions, Washington’s true rank during the Revolutionary War is frequently misstated.

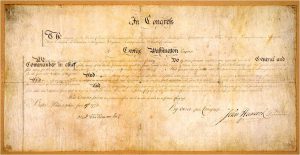

On June 15, 1775, the Continental Congress appointed Washington to lead the newly established Continental Army, saying:

We, reposing special trust and confidence in your patriotism, valor, conduct, and fidelity, do, by these presents, constitute and appoint you to be General and Commander in chief, of the army of the United Colonies, and of all the forces now raised, or to be raised, by them, and of all others who shall voluntarily offer their service, and join the said Army for the Defense of American liberty, and for repelling every hostile invasion thereof.[1]

After the war, Washington became a civilian and, from 1789 to 1797, served as President of the United States, which also made him Commander-in-Chief of the U.S. Armed Forces. Following his second term, Washington again retired to civilian life.

On July 2, 1798, President John Adams appointed Washington as Lieutenant General and Commander of the United States Army. While this may sound like a demotion to some, it was the highest rank authorized at the time, and the one he held until his death.[2]

On January 19, 1976, a joint Congressional resolution recommended that George Washington be promoted to the rank of General of the Armies of the United States. President Gerald R. Ford implemented the resolution by advancing Washington on October 11, 1976, further mandating that no other officer should ever outrank him. This obviously had little effect on the general, as he had been dead for 177 years.[3]

With so many appointments and promotions, it’s no wonder that his Revolutionary War rank can be problematic. Civil War historians have long stated that Ulysses S. Grant’s March 1864 promotion to lieutenant general was the first since Washington held that rank. This is certainly true, but further confuses the issue of Washington’s revolutionary rank. Many authors either misunderstand or are not careful about rank, often incorrectly identifying generals’ proper titles. Many writers credit Washington as either the senior major general or, more frequently, as a lieutenant general. There is even an equestrian statue in Washington, DC, titled “Lieutenant General George Washington.” But his commission specifically states “general.”[4]

The four ascending ranks of general are brigadier, major, lieutenant, and full general, with Washington being at the top grade. A five star rank of General of the Army was approved in 1944, but has been limited to wartime use, with the most recent holder being Omar Bradley in 1950. It is very possible that some congressional delegates in 1775 did not know or perhaps understand the different ranks. Nonetheless, they appointed Washington general, as per his commission. Perhaps the rank was to give more legitimacy to the position and make him equivalent to his potential British counterpart, the overall commander in chief in Great Britain.

Over the next eight years of war, seventy seven additional men would be appointed as either a major general or a brigadier general in the Continental Army, with four declining the honor. Additionally, thirty four officers would be brevetted as brigadier general, and thirteen brigadiers advanced by brevet to major general. At least 120 men would be commissioned as militia generals by the thirteen states. There were no lieutenant generals in the Continental Army. This became a point of historical confusion, especially as related to Washington.

On at least two occasions during the conflict, the Commander-in-Chief recommended that men be appointed to the rank of lieutenant general. Writing to Congress President John Hancock on January 22, 1777, Washington offered that, “As the Army will probably be divided, in the Course of the next Campaign, there ought in my opinion to be three Lieutenant Generals, Nine Major Generals and Twenty Seven Brigadiers.”[5] Further, on January 29, 1778, at Valley Forge, he wrote to the Congressional Camp Committee of adding “to the grand army three Lieutenant-Generals; one to command the right wing, another the left, and a third, the second line.” And perhaps a fourth “on account of contingent services.”[6]

A June 15, 1778 letter to Major General Charles Lee reveals Washington’s motivation:

The mode of shifting the Major Generals from the command of a division in the present tranquil state of affairs to a more important one in action & other capitol movements of the whole army is not less disagreeable to my Ideas, than repugnant to yours, but is the result of necessity; for having recommended to Congress the appointment of Lieutt [sic] Generals for the discharge of the latter duties, & they having neither approved, or disapproved the measure, I am in suspence [sic], and being unwilling on the one hand to give up the benefits resulting from the Command of Lieutt [sic] Generals in the cases abovementd [sic]; or to deprive the Divisions of their Major Genls [sic] for ordinary duty…[7]

Washington was protective of his own position and that of the officer corps as a whole. Given that, it seems impossible that he would have ever petitioned the Congress to promote three or four of his subordinates to the rank of lieutenant general if that were his own rank. Plus, he never signed his letters indicating that rank.

Washington’s proposed army organization for the 1778 campaign did include a role for the expected lieutenant generals or, at least, major generals acting in that capacity. A February 1778 undated document in the papers of Alexander Hamilton, then an aide to the Commander-in-Chief, lists major and brigadier generals. “In the present arrangement of the Army, there will be wanted 11 Major Generals & 25 Brigadiers. 3 Major Generals to act as Lt Generals eight to command divisions.”[8]

It is speculated that the document was prepared by Hamilton probably for presentation to the Committee of Congress, then meeting with Washington at Valley Forge. Perhaps by now, Washington was resolved to not receive the requested lieutenant general position, hence the major general reference.

It is perfectly clear from Congress’s 1775 resolution that George Washington’s rank during the American Revolutionary War was “General.” It is also readily apparent that no one held the rank of Lieutenant General in the Continental Army. It is hoped that future authors will present this remarkable officer’s rank properly.

[1] Library of Congress, American Memory: Journals of the Continental Congress, Saturday, June 17, 1775. Accessed August 25, 2013, http://memory.loc.gov/cgi-bin/query/r?ammem/hlaw:@field(DOCID+@lit(jc00238))

[2] “Papers of the War Department 1784 – 1800.” Accessed August 20, 2013, http://wardepartmentpapers.org/document.php?id=27404. This raises an interesting question of language in that John Adams, as President, was constitutionally Commander in Chief of the Army and Navy of the United States.

[3] “Public Law 94-479-OCT 11, 1976.” Accessed August 20, 2013, http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/STATUTE-90/pdf/STATUTE-90-Pg2078.pdf.

[4] An interesting example is Jonathan G. Rossie’s excellent The Politics of Command in the American Revolution (Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, 1975). In Appendix B on page 219, Rossi lists the Continental General Officers by date of commission, citing Lynn Montross’ Rag, Tag and Bobtail: The Story of the Continental Army as the source. However, Rossi changes Montross’ listing of Washington from General and Commander in Chief to that of first major general. Numerous such examples exist, some of which can be found by googling Lieutenant General George Washington. The Lieutenant General equestrian statue is featured on Wikipedia: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lieutenant_General_George_Washington. Douglas Southall Freeman gets it right in his George Washington: A Biography, Vol. 3, saying, “The highest rank, after Washington’s own, was to be that of Major General. No Lieutenant Generals were provided.” after 435.

[5] Frank E. Grizzard, Jr, editor, The Papers of George Washington, Revolutionary War Series, Vol. 8 (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1998) 127.

[6] Edward G. Lengel, editor, The Papers of George Washington, Revolutionary War Series, Vol. 13 (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 2003) 384.

4 Comments

Some Continental Army officers and soldiers referred to Washington as “generalissimo,” or general atop all the generals. Pvt. Samuel Haws wrote in his 1775 diary about the arrival in Cambridge of “General Washington Lesemo,” so he was still getting used to the title.

Another rank used at the time was “captain general,” as in Nathaniel Folsom’s June 1775 report to the New Hampshire government: “Mr. [Artemas] Ward is Capt. General, Mr. [John] Thomas Lieut. General, and the other Generals are Major Generals.” But I don’t think the Continental government ever used that rank.

And there’s the unofficial but often used title, His Excellency, General George Washington.

Hello: What are the generals silver stars made in and is it five pointed or six pointed stars , the size and style and is it made in stamp metal or was it silver embrodiey? Is there any way I can get an email photo of George Washington of the three stars that he wore during his military service? Kind regards: Randy Lee

The excellent article above appears to contain an error. The legislation reviving the Office of General of the Armies, to which George Washington was appointed with a date of rank of 4 July 1975, did not specify that he was to be senior to all military officers. Instead, the exact wording specified that he was to be senior to all US Army officers. Nothing was said about naval officers (or air force officers).

The legislative history behind the authorization for General Washington’s posthumous appointment is unclear as to Congress’ true intent. Some advocated for him to be — explicitly — senior to all US military officers, ever. But others were clear that they considered him to be junior to the US Navy fleet admirals (5-stars) of WWII. No decisions were left on the record to resolve these discrepancies, and we today are left with the wording of the law that only tells us that he is senior to other US Army officers. Why is this important? Because at least until WWII, the Navy and Army used completely different systems to determine rank and promotions, equivalency between them was based on “unwritten regulations,” and at times one or the other did or did not have 3- or even 4- star officers, or appointed their highest officers with additional honorific titles like “commander in chief,” or “general in chief,” or “commanding general of the army,” or “admiral of the navy.” Congress never explained the seniority — in law — amongst these worthy officers. And the appointment of General of the Armies Washington did not clarify it, either, except as his seniority vis a vis other US Army officers.