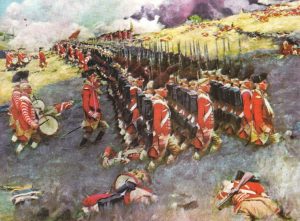

Gotta love those redcoats, mechanically marching in neatly aligned ranks into the slaughtering fire of rebel marksmen hidden behind earthworks. This is the iconic image of the Battle of Bunker Hill, painted by Howard Pyle in 1897. Rendered over 100 years after the fact, we’d expect a few issue with the painting; none of us was there to witness what the battle actually looked like, but surviving eyewitness accounts give a pretty good indication that it didn’t look nearly as orderly – or mindless – as Pyle depicts.

There can be no doubt that the professional British soldiers who took part in the assault were well trained and highly experienced. Pyle seems to show the right side of the British force which was composed of grenadier companies from regiments in the Boston garrison – among the tallest, hardiest, most experienced and reliable men in each regiment. They were certainly capable of marching in close, straight lines, but they were also smart enough to know better. Granted, the grenadiers had suffered heavy casualties the previous April while marching to Concord and back, but new men had been brought in from their regiments to refill the ranks, and policy was strict about selecting only appropriately experienced men.[1] The initial purpose of their march up the hill was as a feint while fast-moving troops turned the American flank along the beach, but that flank attack was thwarted, leaving the grenadiers to make a frontal assault.[2]

The key to such an attack was speed, but here that was impossible; fences, brick kilns, enclosures and other obstructions impeded progress.[3] The fences could not be quickly broken down, so the grenadiers had to climb over each one. Howard Pyle’s neat, straight ranks, had they existed at the base of the hill, quickly deteriorated into men struggling to make their way forward over obstacles in the face of heavy fire. Every bit as brave and determined as Pyle’s painting, but not nearly as tactically foolhardy.

In addition to the rigidly straight lines moving over smooth unimpeded ground, the formation shown by Pyle is inaccurate. Although the standard training manual used by the British called for three-rank formations (that is, three rows of soldiers) in close order, practical conditions in America led to the adaptation of two ranks with wider spacing between the men – ideal for moving over the type of uneven ground and obstacles at Bunker Hill. Experienced men, well trained in close order drill, could maintain good order in these looser, more flexible formations that were already in use when this early-war battle occurred.[4]

As for those drummers, an integral part of the army, there’s doubt as to whether they played marching cadences in battle. While the sound of the drum was impressive for marching parties of troops around Boston streets, there is much evidence that drums were used only for relaying signals on the battlefield, and sometimes were not used at all.[5]

There’s no point in being snarky about the accuracy of the soldiers’ clothing; Pyle’s uniforms exhibit a curious mix of features from the 1770s through the 1820s, but, hey, he wasn’t a military historian and he gets the general point across. One prominent detail, however, is highly misleading: those huge heavy knapsacks. Although British soldiers did use knapsacks (that didn’t look anything like Pyle’s), they didn’t wear them on that day. Why would they? The knapsack carried nice things like spare shoes, shirts and socks, great for a long campaign but silly to lug along when attacking a fort only a mile away from your barracks. In preparation for the assault, General Howe explicitly ordered the troops to march with only “with their Arms, Ammunition, Blankets, and provisions;”[6] the latter two items because he correctly anticipated that they’d spend the night camped under the stars after the attack. Knapsacks remained behind in barracks like they usually did, to be brought up later in wagons when an encampment was firmly established. Pyle can’t be blamed too heavily, though; authors have for years written that British troops hauled their knapsacks up Bunker Hill, one even doing so after presenting the order to carry only blankets.[7]

For all that, it’s a nice enough painting, as long as you’re not using it to get a good impression of the Battle of Bunker Hill.

[1] Ages and experience of British grenadiers is discerned by compiling information from regimental muster rolls, WO 12, and soldiers’ discharges, WO 97, WO 119 and WO 121, all British National Archives, Kew, England.

[2] Don N. Hagist, “Shedding Light on Friendly Fire at Bunker Hill”, American Revolution Vol. 1 No. 3 (October 2009), 4-10.

[3] Martin Hunter, The Journal of Gen. Sir Martin Hunter (Edinburgh: The Edinburgh Press, 1894), 10-11.

[4] Matthew H. Spring, With Zeal and Bayonets Only: The British Army on Campaign in North America, 1775-1783 (Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press, 2008), 140.

[7] The error appears as early as 1794 when Charles Stedman wrote that the troops were “encumbered with three days provisions, their knapsacks on their backs” and estimated their total burden at 125 pounds. Although Stedman served in America (but not at Bunker Hill) and is in many ways reliable, his estimate of the soldier’s burden is nearly twice other estimates for a fully loaded soldier – and the men at Bunker Hill were not fully loaded. Charles Stedman, The History of the Origin, Progress and Termination of the American War (London, 1794), 128. The author who presented the order but then mentioned knapsacks is Harold Murdock, Bunker Hill Notes and Queries (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1927), 14, 27.

8 Comments

Good analysis, but I still love this artwork as a “history painting,” if not as history.

Incidentally, another thing that’s wrong with Pyle’s canvas is that it’s been stolen.

These paintings are fun to analyze from a historical accuracy perspective. Like Washington Crossing the Delaware or the Signing of the Declaration of Independence, story telling, not historical accuracy, was the goal.

However as you pointed out, the inaccuracies of this painting tell a story that suggests that antiquated/ignorant tactics played a role in the large British casualties that day. Paintings like this can lead to misunderstandings about British military tactics during the Revolution.

Yet having said this, the painting is really nice!

When first published in Scribner’s Magazine for February 1898, the picture’s caption (written by Pyle himself or from notes provided by Pyle) stated:

“The scene represents the second attack and is taken from the right wing of the Fifty-second Regiment, with a company of grenadiers in the foreground. The left wing of the regiment, under command of the major, has halted, and is firing a volley; the right wing is just marching past to take its position for firing. The ship-of-war firing from the middle distance is the [HMS] Lively; in the remoter distance is the smoke from the battery at Copp’s Hill. The black smoke to the right is from the burning houses of Charlestown.”

Whether he got things right is another thing: Pyle was only as accurate as his sources – many of which were incomplete, misinformed, or out of reach. In the case of “Bunker Hill”, Pyle’s secretary recalled:

“When Mr. Pyle was collecting information and ideas for this painting he wrote to the Admiralty office in London for details about the real formation in the battle, but got very little information. He made the composition from what they told him, and from his own imagination. At first the drummers were marching on the right side, and then he put them in the rear where they are now.…”

And it might be of use to quote an 1897 letter he wrote to historian Paul Leicester Ford (who had criticized details some other works by Pyle):

“It was my endeavor to make the work as accurate as possible, but, as you may easily understand, extreme difficulty lies in the way of an illustrator.

“In the first place of all, it is next to impossible for a man, so busy as I am, to obtain all the details for everything he does so that there shall be no mistake in his work. It is, as you know, not a matter of days, but of weeks to get together the material even for a single paper. It is almost impossible for each picture an illustrator makes, that like care shall be observed.

“In the second place, the historic writer has a great advantage over the draughtsman, in that he need not necessarily state the most minute point in his work. If he is uncertain as to any single part, he may slur that and pass on to something else. The illustrator must have everything as perfectly accurate as he can render it, for the picture represents not only the general description, but a description so particular that it may take pages upon pages to fulfill it in literature.

“In the third place, the illustrator becomes so wrapped up in the dramatic intent of the subject that he oftentimes is not aware of inaccuracies of detail until the whole thing is depicted – in which case, to undo the work means to redraw the whole subject – a matter which is often impracticable because of the delay in which it involves the publisher.”

The nice thing about art is the story it tells.

In the midst of the mindlessness of battle. Only one man (the third man in the third row) takes notice of the fallen.

Perhaps the war was not desired by Britain and, although waste of human life never occurs in war, high death count may have been desired to cause demand in Britain to resolve the conflict as soon as possible.

While it’s correct that the British at Bunker Hill had adopted the two-rank line, the same passage from Spring (p.140) also points out that they retained their close order and moved up the hill slowly and haltingly. It wasn’t until February 1776, as Spring notes on p.141, that Howe first ordered troops to form at 18 inch files distances.

A good book on Bunker HIll is “Now We Are Enemies” by Thomas Flemming. He mentions the packs specifically. He notes that the British we planning an attack around the flank of the American positions surrounding Boston. When they saw the emplacement on Bunker Hill, the plan evolved to overrunning the fort and then striking on as originally planned. For a mobile operation covering several miles, the men would need their backpacks.

Flemming also notes that they wore the packs in the first two assaults and only on the third assault late in the day did most of the men remove their packs.

I’ve always figures this painting to show the second assault after the failure of the first, hence the red carpet effect of the fallen. and the fact that the men are still wearing their backpacks.

Respectable though Fleming’s work is, he is wrong about the knapsacks.

As stated in the article above, the orders given to British troops on June 17 were quite explicit:

“General Morning orders, 10 o’Clock 17th June 1775

“The ten oldest companies of Grenadiers and the ten oldest companies of light Infantry, (exclusive of the Regiments lately landed) the 5th and 38th Regiments, to parade half after eleven o’Clock, with their Arms, Ammunition, Blankets, and provisions ordered to be cooked this morning, they will march by files to the long wharf.” [General Orders, America. WO 36/1, The National Archives, Kew, Richmond, Surrey, p. 108-109].

Captain George Harris, commander of the 5th Regiment’s grenadier company, wrote that “Our blankets had been flung away during this engagement” [Samuel Adams Drake, Bunker Hill: The Story Told in Letters (Boston: Nichols and Hall, 1875), 37], while Ensign William Carter of the 40th Regiment recalled, “The night of the 17th the remainder of the army lay on their arms, on this ground, and encamped as soon as the equipage could be transported to this side of the water” [William Carter, A genuine detail of the several engagements, positions, and movements of the Royal and American armies, during the years 1775 and 1776 (London, 1784), 5].

No British participant gives any indication that the troops carried knapsacks during this battle; as stated in the article above, the first suggestion of it came from a writer who was not even in Boston at the time of the battle (Charles Stedman, The History of the Origin, Progress and Termination of the American War (London, 1794)).

If there was any expectation of British troops advancing beyond Bunker Hill after the battle, getting their knapsacks to them within the next few days would be a simple matter, and consistent with the way that the British army campaigned throughout the war.

The Painting was apparently stolen [Wikipedia]

This painting’s whereabouts are unknown as it was probably stolen from the Delaware Art Museum in 2001

Fishman, Margie (2014-05-18). “First painting auctioned by museum could bring $13.4 million”. The News Journal. Wilmington, DE, US. Retrieved 2021-11-24.