Source: U.S. Senate

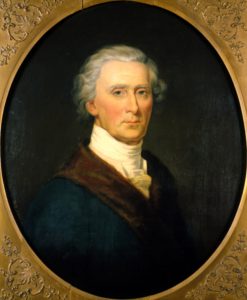

“Give me liberty or give me death!” shouted Patrick Henry to the members of the Second Virginia Convention in 1775. His words became the first great war cry of the American Revolution. In 1776 this backwoods lawyer was elected governor of Virginia, the largest state in the new American union.

Henry was descended from Scottish Presbyterians who had settled in Virginia’s back country. They had brought with them from their homeland a profound suspicion of British rule. For centuries Britain had oppressed Scotland and crushed her attempts to rebel and win independence.

That undoubtedly explains why Patrick Henry’s fellow Scottish Americans were well represented in the revolutionary ranks. Perhaps their best known warrior was Commodore John Paul Jones, the naval hero who was born in Kirkcudbrightshire, Scotland. In 1779, the slim hot-tempered Jones commanded a five warship flotilla that circled the British Isles, capturing seventeen merchant ships. He capped this performance by defeating the British man of war HMS Serapis off the English coast, while thousands of dismayed Englishmen watched from the shore.

Another bold Scot, big beefy bookseller Henry Knox, fought as a volunteer at the 1775 battle of Bunker Hill. A few weeks later, General Washington met Knox in Cambridge, and was so impressed with his military knowledge that he asked him to join his headquarters staff.

The American army was desperately short of cannon. In the winter of 1776, Knox organized teams of men and oxen who hauled over sixty heavy guns from Fort Ticonderoga in New York to Boston — a 300 mile journey up and down the steep snowy slopes of the Berkshire Mountains. Some of the guns weighed more than a ton. Washington used the cannon to drive the British out of Boston. Knox soon became chief of artillery in the Continental Army.

The Irish were not far behind the Scots in the boldness game. John Sullivan of New Hampshire was the son of a schoolteacher from Ireland’s County Limerick. In December 1774, four months before the shooting war began, Sullivan learned that the British planned to station a regiment at Fort William & Mary in Portsmouth, New Hampshire’s capital, to intimidate the patriots.

Sullivan led a raid on the fort early the next day. His men overwhelmed the small British garrison, hauled down the flag, and carried off one hundred barrels of gunpowder. Some of that powder was used with deadly effect six months later at the battle of Bunker Hill. Sullivan was soon a major general in Washington’s army, famed for his fearlessness under fire.

Another Irishman — in fact — a whole family of them — struck the first blow against the English on the sea. In May, 1775, a month after the battles of Lexington and Concord, the British sloop-of-war, HMS Margaretta entered Machias Bay, Maine, home of Maurice O’Brien of Cork, and his five sons. The O’Briens organized a group of local fishermen who put to sea in their boats and captured the befuddled British sailors by boarding them in a wild rush. In Boston, the infuriated English admiral sent two more sloops north to regain Margaretta. The salty O’Briens and their neighbors captured them too.

Probably the most famous Irish-American leader was Charles Carroll of Maryland. Writing under the pen name “First Citizen,” he persuaded Maryland to join the Revolution. Carroll was educated in France by his wealthy father and came home to become the richest man in America by 1776. Yet Carroll did not hesitate to sign the Declaration of Independence.

Carroll knew he was risking a death sentence for treason and the confiscation of his wealth if America lost the war. He took the risk because he knew from his family’s experience in Ireland what would happen if Britain was allowed to oppress Americans with taxes and laws passed by a parliament in which they did not have a single representative. Americans would have been as ruthlessly exploited as the Irish in Ireland.

Less well known is the story of a working class Irishman, big hearty Hercules Mulligan. He shocked his American friends by welcoming the redcoated British regiments when they captured New York in 1776. A skilled tailor, Mulligan was soon making money outfitting British officers and wealthy Americans who had remained loyal to the king.

Beyond the city limits, Americans shook their heads. Who could believe Mulligan had become a traitor? He had seemed to be a fervent patriot.

Mulligan still was, but only a few people knew it. One of these insiders was General George Washington. Another was Washington’s aide, Colonel Alexander Hamilton, who was a close friend of Mulligan. Throughout the war, the Irishman was one of America’s most valuable spies. Among other things, he warned Washington of a well-organized British plot to kidnap him.

At the end of the war, the British evacuated New York. Not a few American hotheads vowed that they would make Mulligan sorry for his treachery. Imagine their surprise when General Washington rode into the city at the head of his troops and announced that the following morning he planned to have breakfast with his friend, Hercules Mulligan.

8 Comments

Thank you for the interesting article to add to your other contributions to date. I’m sure if one were to go back a generation or two in ancestry as of 1776, there would be lots of Celts found fighting for the Americans. My favorite would have to be Daniel Morgan, grandson to four Welsh grandparents.

Do you know how many Americans at the time were Scotch/Irish? I have heard that they made up a large percentage of the American forces (especially the Presbyterians.) Others have said they were pretty rare.

Patrick Henry was not speaking to members of the Continental Congress in the spring of 1775. He spoke on the third day of the Second Virginia Convention, whic was meeting in Richmond, Virginia.. The convention did select the delegates who would represent Virginia in the 2nd Continental Congress.

You’re absolutely right, Michael. Thank you. Corrected.

By looking at a few individuals but grouping them under the title “Celts in the American Revolution”, the impression is given that these men supported the rebellion because of their Scottish heritage. But there’s no evidence that Patrick Henry, for example, would’ve had different political leanings if his heritage had been English or German or what have you.

There were many thousands of Scots, and Irish and other nationalities, on both sides of the conflict among all ranks of the armies and the governments. To single out individuals of one ethnicity on one side gives the impression that everyone (or a majority) of that ethnicity tended to be on that side – which wasn’t the case, at least with the Scots and the Irish.

The Scots will have the opportunity in the fall of 2014 to show what they are made of when they hold the independence referendum. It’s been a long time since 1707 and they just might do it.

Would’t that be exciting if Scotland became a sovereign nation. It’s been several centuries since I’ve been to the homeland, but what a splendid motivation.

Let’s not forget that Alexander Hamilton was of Scottish descent by his father.

His mother was French Huguenot but it was with this Scottish line with which he identified.